The theory of meridians and collaterals studies the distribution, physiological functions, pathological changes of the human meridian system, and its relationship with the organs. It is an important component of the theoretical system of traditional Chinese medicine. The theory of meridians and collaterals was developed by ancient physicians through long-term medical practice and has guided the diagnosis and treatment in various branches of TCM for many years, particularly closely related to acupuncture.

Meridians refer to the main and collateral channels. The term “jing” (经) implies a pathway, where the main channels connect the upper and lower parts of the body and communicate internally and externally; “luo” (络) refers to the branches of the main channels, which are smaller and interwoven throughout the body. As stated in the “Lingshu: Pulse Measurement”: “The main channels are internal, while the branches that spread horizontally are the collaterals; the branches of the collaterals are called ‘sun’ (孙).”

Meridians connect internally to the organs and externally to the limbs, linking the internal organs with the body surface, forming an organic whole. They facilitate the flow of qi and blood, nourish yin and yang, and maintain the coordinated and relatively balanced functional activities of the body. In clinical acupuncture treatment, the differentiation of syndromes, selection of acupoints along the meridians, and techniques of tonifying or reducing all rely on the theory of meridians. Therefore, the “Lingshu: Meridian Differentiation” states: “The twelve main channels are the basis of life, the cause of disease, the means of treatment, and the origin of illness; they are where learning begins and where work stops.” This highlights the significant importance of meridians in physiology, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment, which has been emphasized by physicians throughout history.

Naming of Meridians

The meridian system is mostly named according to yin and yang. All things can be divided into yin and yang, and the two are interrelated. The naming of meridians embodies this meaning. One yin and one yang evolve into three yin and three yang, which correspond to each other (interior and exterior correspond).

Taiyin —– Yangming

Shaoyin —– Taiyang

Jueyin —– Shaoyang

The three yin and three yang are classified based on the abundance (or deficiency) of yin and yang qi: the most abundant yin is Taiyin, followed by Shaoyin, and then Jueyin; the most abundant yang is Yangming, followed by Taiyang, and then Shaoyang. The “Suwen: Great Discussion on the True Essentials” states: “I wish to hear about the three aspects of yin and yang; what are they?” “Qi has different amounts and uses.” “What is Yangming?” “It is the convergence of two yangs.” “What is Jueyin?” “It is the complete intersection of two yins.”

The names of the three yin and three yang are widely used in the naming of meridians, including main channels, collateral channels, and sinew channels. The three yin of the hand (Hand Taiyin, Hand Shaoyin, Hand Jueyin) are located on the inner side of the upper limb, while the three yang of the hand (Hand Yangming, Hand Taiyang, Hand Shaoyang) are on the outer side; the three yang of the foot (Foot Yangming, Foot Taiyang, Foot Shaoyang) are on the outer side of the lower limb, while the three yin of the foot (Foot Taiyin, Foot Shaoyin, Foot Jueyin) are on the inner side. The naming of the meridians of the hands and feet shows that the formation of the theory of meridians is closely related to the limbs.

In the silk manuscripts unearthed from the Mawangdui Han tomb, there are two versions regarding the eleven channels (the second version is further divided into A and B, with the text being basically the same), which are earlier than the “Neijing” in ancient literature on meridian theory. The names of the eleven channels are based on the division of yin and yang by “arms” and “feet,” consistent with the significance of dividing yin and yang in the hands and feet.

Composition of the Meridian System

As a channel for the flow of qi and blood, the meridian system is primarily based on the twelve main channels, which “internally belong to the organs and externally connect to the limbs,” linking the internal and external aspects of the body into an organic whole. The twelve collaterals are important branches of the twelve main channels located in the chest, abdomen, and head, connecting the organs and enhancing the relationship between the interior and exterior channels. The fifteen collateral channels are important branches of the twelve main channels located in the limbs and the front, back, and sides of the trunk, serving to connect the interior and exterior and facilitate the flow of qi and blood. The eight extraordinary vessels are special channels that regulate and connect the other meridians, adjusting the abundance and deficiency of qi and blood. Additionally, the external aspects of the meridians also govern the muscles and skin, which are divided into twelve sinew channels; the skin is also categorized according to the distribution of the meridians into twelve skin areas.

Overview of the Twelve Main Channels

The twelve main channels are the main content of the theory of meridians. “The twelve main channels internally belong to the organs and externally connect to the joints,” summarizes the distribution characteristics of the twelve main channels: internally, they are subordinate to the organs; externally, they are distributed throughout the body. Since the main channels are responsible for the flow of qi and blood, their pathways have a specific direction, referred to as “the flow of the channels in reverse and forward,” later termed “flowing.” The main channels are also interconnected through branches, which is referred to as “the correspondence between the interior and exterior, all having their respective connections.”

Pathways of the Twelve Main Channels

The pathways are as follows: the three yin channels of the hand run from the chest to the hand, the three yang channels of the hand run from the hand to the head, the three yang channels of the foot run from the head to the foot, and the three yin channels of the foot run from the foot to the abdomen (chest). As stated in the “Lingshu: Reversal and Weight Loss”: “The three yin of the hand run from the organs to the hand, the three yang of the hand run from the hand to the head, the three yang of the foot run from the head to the foot, and the three yin of the foot run from the foot to the abdomen.”

Overview of the Eight Extraordinary Vessels

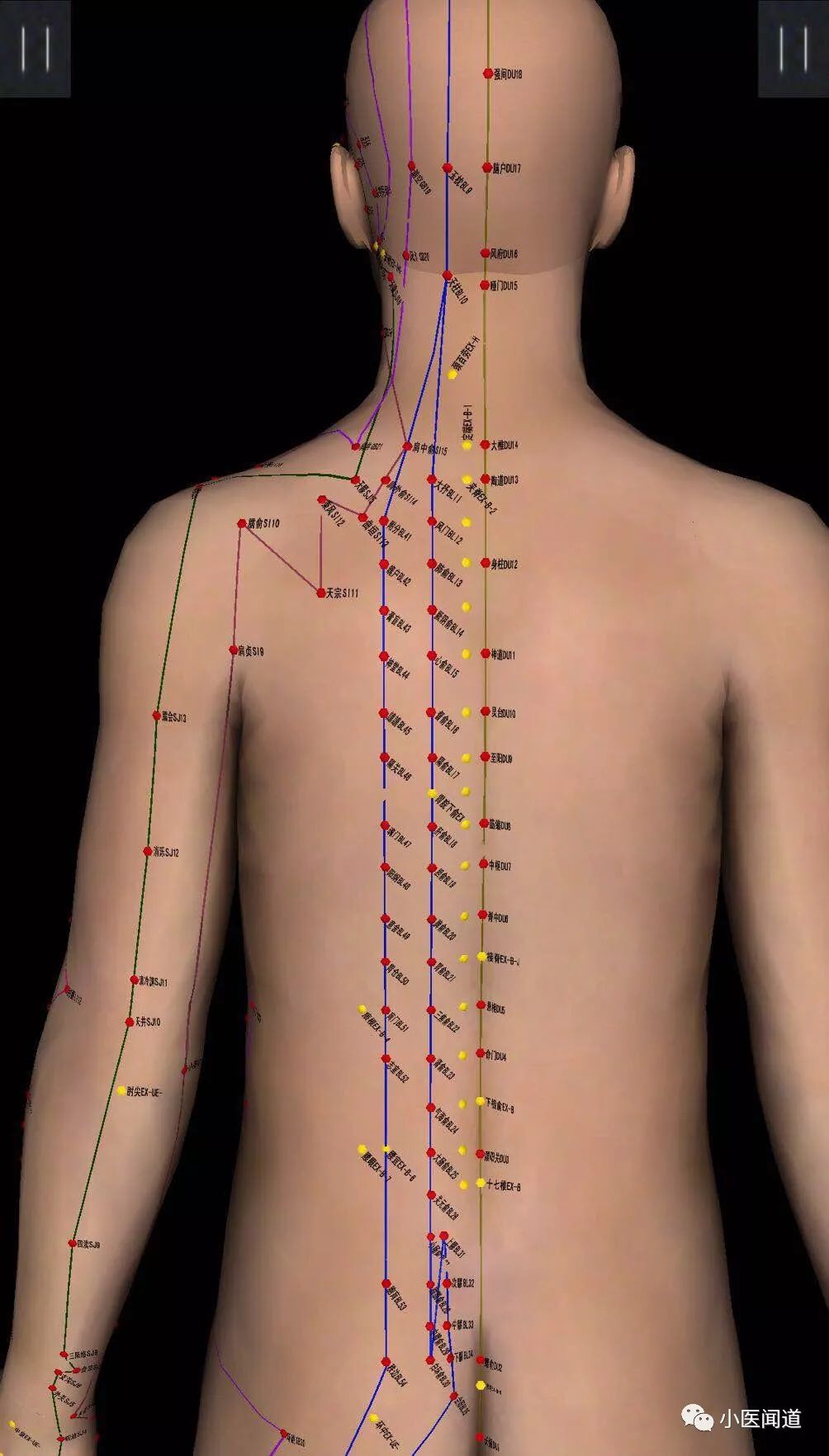

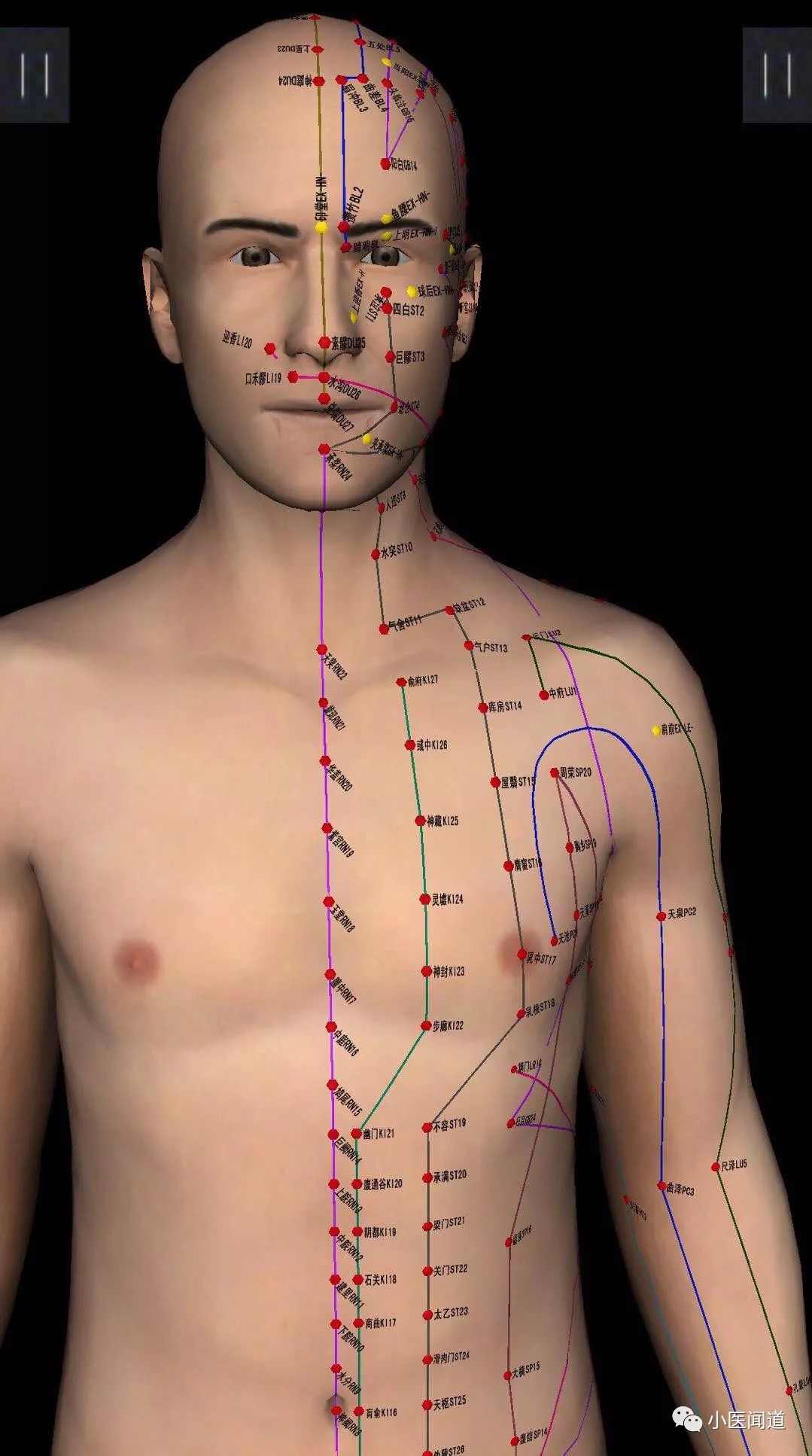

The eight extraordinary vessels refer to the Du (督) vessel, Ren (任) vessel, Chong (冲) vessel, Dai (带) vessel, Yinwei (阴维) vessel, Yangwei (阳维) vessel, Yinqiao (阴跷) vessel, and Yangqiao (阳跷) vessel. Unlike the twelve regular channels, they do not directly belong to the organs and do not have an interior-exterior relationship, hence they are called “extraordinary vessels.” The Du, Ren, and Chong vessels all originate from the lower abdomen, sharing a common origin at the perineum, referred to as “one source with three branches.” The Du vessel runs along the midline of the back, reaching the head and face; the Ren vessel runs along the midline of the chest and abdomen, reaching the chin; the Chong vessel ascends alongside the Foot Shaoyin Kidney channel, encircling the lips. The Dai vessel originates from the sides of the abdomen, encircling the waist. The Yinwei vessel originates from the inner side of the lower leg, ascending along the inner thigh to meet the Ren vessel at the throat. The Yangwei vessel originates from the outer side of the foot, ascending along the outer side of the leg to meet the Du vessel at the back of the neck. The Yinqiao vessel originates from the inner side of the heel, ascending alongside the Foot Shaoyin and other channels to meet the inner canthus of the eye with the Yangqiao vessel. The Yangqiao vessel originates from the outer side of the heel, ascending alongside the Foot Taiyang and other channels to meet the inner canthus of the eye with the Yinqiao vessel, and runs along the Foot Taiyang channel to the forehead, meeting the Foot Shaoyang channel at the back of the neck.

The eight extraordinary vessels crisscross and distribute among the twelve main channels, primarily reflecting two aspects of their function. First, they connect the relationships between the twelve main channels. The eight extraordinary vessels link channels that are close in location and similar in function, achieving the regulation of related channels’ qi and blood and coordinating yin and yang. The Du vessel is connected to the six yang channels, known as the “sea of yang channels,” which regulates the qi of all yang channels; the Ren vessel is connected to the six yin channels, known as the “sea of yin channels,” which regulates the qi of all yin channels; the Chong vessel is connected to the Ren and Du vessels, as well as the Foot Yangming and Foot Shaoyin channels, hence it is referred to as the “sea of twelve channels” and the “sea of blood,” which has the function of containing the qi and blood of the twelve channels; the Dai vessel restrains and connects the various longitudinal channels of the body; the Yinwei and Yangwei vessels connect the yin and yang channels, respectively governing the exterior and interior of the body; the Yin and Yangqiao vessels govern the movement of the lower limbs and the states of wakefulness and sleep. Second, the eight extraordinary vessels regulate the accumulation and distribution of qi and blood in the twelve channels. When the qi and blood of the twelve channels and organs are abundant, the eight extraordinary vessels can store them; when the body’s functional activities require it, the eight extraordinary vessels can also distribute and supply them.

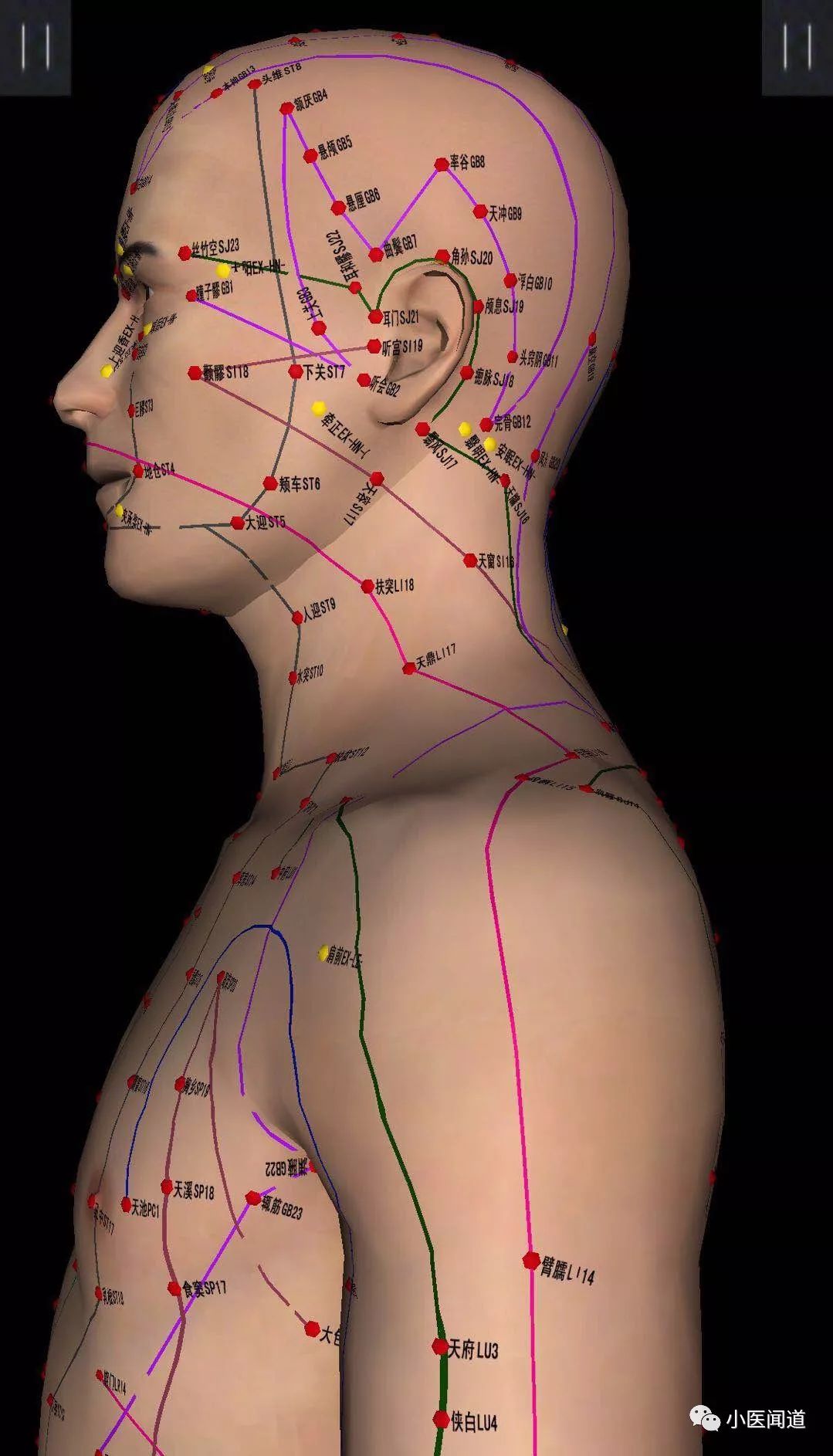

The points of the Chong, Dai, Qiao, and Wei vessels are all associated with the twelve channels and the Ren and Du vessels, but the Ren and Du vessels each have their own associated points, thus they are collectively referred to as the “fourteen channels.” The fourteen channels have specific pathways, symptoms, and associated points, forming the main part of the meridian system, which serves as the foundation for acupuncture treatment and the application of herbal medicine in clinical practice. The distribution of the fourteen channels is illustrated in the diagram.

Functions of the Meridians

1. Physiological Functions of the Meridians

The meridians serve to connect the organs and limbs. The five zang organs, six fu organs, limbs, and other tissues and organs, although each has different physiological functions, collectively engage in organic activities, maintaining a coordinated unity between the internal and external aspects of the body, forming an organic whole. This interconnection and organic cooperation are primarily realized through the communication function of the meridian system. The twelve main channels and their branches crisscross, connecting the internal organs, while the eight extraordinary vessels communicate between the twelve channels, and the sinew channels connect the muscles and skin of the limbs, thereby linking the various zang-fu organs organically, as stated in the “Lingshu: Sea Discussion”: “The twelve main channels internally belong to the organs and externally connect to the joints.”

The meridians also facilitate the flow of qi and blood, nourish the entire body, resist external pathogens, and protect the body. All organs and tissues require the nourishment of qi and blood to function normally. Qi and blood are the material basis for life activities and must rely on the meridians for distribution throughout the body to nourish and moisten all organs and tissues, maintaining normal bodily functions, such as nourishing the qi and regulating the five zang organs, and dispersing it to the six fu organs, which provides the material conditions for the functional activities of the five zang organs and six fu organs. Therefore, the “Lingshu: Ben Zang” states: “The meridians are responsible for the flow of blood and qi, nourishing yin and yang, moistening the muscles and bones, and benefiting the joints.” This indicates that the meridians have the function of circulating qi and blood, regulating yin and yang, and nourishing the entire body. Since the meridians can “circulate blood and qi and nourish yin and yang,” the nourishing qi flows within the channels, while the defensive qi circulates outside the channels, allowing the nourishing and defensive qi to permeate the entire body, enhancing the body’s defensive capacity, thus playing a role in resisting external pathogens and protecting the body. Hence, the “Lingshu: Ben Zang” states: “When the defensive qi is harmonious, the flesh is relaxed, the skin is soft, and the pores are dense.”

2. Clinical Applications of Meridian Theory

(1) Explaining Pathological Changes

In cases of deficiency of the righteous qi and invasion of pathogens, the meridians are also the pathways for the transmission of pathogens. When the body surface is invaded by pathogens, they can enter through the meridians from the exterior to the interior, from superficial to deep. For example, when external pathogens invade the skin, initial symptoms may include fever, chills, headache, and body aches. Since the lungs are associated with the skin and hair, external pathogens can follow the meridians and settle in the lungs, leading to symptoms such as cough, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and chest pain. The “Suwen: Misdiagnosis” states: “When a pathogen invades the body, it must first settle in the skin and hair, linger without leaving, enter the sun meridian, linger without leaving, enter the collateral meridian, linger without leaving, and enter the main meridian, connecting to the five zang organs and dispersing to the intestines.” This indicates that the meridians are the pathways for external pathogens to transmit from the skin and pores to the internal organs. Additionally, the meridians are also channels for the mutual influence of pathological changes between the organs and between the organs and the surface tissues. For example, heat from the heart can affect the small intestine, liver disease can impact the stomach, and stomach disease can affect the spleen, which is the result of the interrelated pathological changes of the organs through the meridians. Internal organ changes can also reflect on the surface tissues, such as liver disease causing rib pain, kidney disease causing lower back pain, and heart fire causing sores on the tongue, while heat in the large intestine or stomach can lead to swollen and painful gums, etc. All of these illustrate that the meridians are pathways for the transmission of pathogens.

(2) Guiding Syndrome Differentiation and Meridian Selection

Due to the specific pathways and organ affiliations of the meridians, they can reflect the diseases of the associated organs. Therefore, in clinical practice, the symptoms of diseases can be used in conjunction with the pathways of the meridians and the associated organs as the basis for syndrome differentiation and meridian selection. For example, in the case of headache, the location of pain can be differentiated based on the distribution of the meridians in the head: pain in the forehead is often related to the Yangming channel, pain on the sides is often related to the Shaoyang channel, pain in the neck is often related to the Taiyang channel, and pain at the top of the head is often related to the Jueyin channel. Similarly, pain in the ribs or lower abdomen is often related to the liver channel, as the ribs and lower abdomen are traversed by the liver channel. Furthermore, during the course of certain diseases, it is often observed that there are significant tenderness, nodules, or cord-like reactions along the pathways of the meridians or at certain acupoints where qi accumulates, as well as changes in skin morphology, temperature, and electrical resistance, which can also assist in diagnosing diseases. For instance, patients with intestinal abscesses may sometimes exhibit tenderness at the Shangjuxu point of the Foot Yangming Stomach channel; patients with long-term indigestion may sometimes show abnormal changes at the Pishu point. In clinical practice, methods such as meridian examination, acupoint palpation, and meridian electrical measurement can be used to check for changes in the relevant meridians and acupoints, providing diagnostic references.

(3) Guiding Acupuncture Treatment

Acupuncture treatment involves needling and moxibustion at acupoints to unblock the flow of meridian qi, restoring the regulation of qi and blood in the organs, thereby achieving therapeutic effects. Acupoint selection is generally based on clear syndrome differentiation; in addition to selecting local acupoints, it usually focuses on meridian selection, meaning that if a certain meridian or organ is affected, the corresponding distal acupoints of that meridian or organ are selected for treatment. The “Four Total Acupoints Song” states: “For abdominal pain, select Sanli; for back pain, select Weizhong; for headache, select Yinjiao; for facial issues, select Hegu,” which is a good illustration of meridian selection and is widely applied in clinical practice. For example, for stomach pain, distal points such as Zusanli and Liangqiu are selected; for rib pain, distal points such as Yanglingquan and Taichong are selected. Additionally, for headaches, if the pain is in the front, which is related to the Yangming channel, distal points such as Hegu on the upper limb and Neiting on the lower limb can be used for treatment. Furthermore, based on the close relationship between the skin and the meridians and organs, clinical practice may involve using skin needles to prick the skin or embedding needles under the skin to treat organ and meridian-related conditions; according to the theory of “removing the cause by pricking,” bloodletting through pricking can also be used to treat common diseases, such as pricking the Taiyang point for red and swollen eyes, pricking the Shaoshang point for sore throat, and pricking the Weizhong point for acute lumbar sprain, etc.; conditions of the sinews often manifest as spasms, stiffness, and convulsions, and treatment often involves selecting local acupoints, known as “using pain as a guide.” All of these reflect the application of meridian theory in acupuncture treatment.

Meridians play an important role not only in the physiological functions of the body but also as a crucial theoretical basis for explaining pathological changes, guiding syndrome differentiation and meridian selection, and acupuncture treatment. Therefore, the “Lingshu: Meridians” states: “The meridians are what can determine life and death, address all diseases, and regulate deficiency and excess; they must be unobstructed.”

Discussion on Meridians

Hand Taiyin Lung Channel

The Hand Taiyin Lung channel primarily distributes along the inner side of the upper limb’s anterior edge, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Hand Yangming Large Intestine Channel

The Hand Yangming Large Intestine channel primarily distributes along the outer side of the upper limb’s anterior edge, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Yangming Stomach Channel

The Foot Yangming Stomach channel primarily distributes along the head, face, second lateral line of the chest and abdomen, and the anterior edge of the outer side of the lower limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Taiyin Spleen Channel

The Foot Taiyin Spleen channel primarily distributes along the second lateral line beside the Ren channel in the chest and abdomen and the anterior edge of the inner side of the lower limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Hand Shaoyin Heart Channel

The Hand Shaoyin Heart channel primarily distributes along the inner side of the upper limb’s posterior edge, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Hand Taiyang Small Intestine Channel

The Hand Taiyang Small Intestine channel primarily distributes along the outer side of the upper limb’s posterior edge, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Taiyang Bladder Channel

The Foot Taiyang Bladder channel primarily distributes along the first and second lateral lines of the lower back and the posterior edge of the outer side of the lower limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Shaoyin Kidney Channel

The Foot Shaoyin Kidney channel primarily distributes along the posterior edge of the inner side of the lower limb and the first lateral line of the chest and abdomen, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Hand Jueyin Pericardium Channel

The Hand Jueyin Pericardium channel primarily distributes along the middle of the inner side of the upper limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Hand Shaoyang Sanjiao Channel

The Hand Shaoyang Sanjiao channel primarily distributes along the middle of the outer side of the upper limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Shaoyang Gallbladder Channel

The Foot Shaoyang Gallbladder channel primarily distributes along the middle of the outer side of the lower limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Foot Jueyin Liver Channel

The Foot Jueyin Liver channel primarily distributes along the middle of the inner side of the lower limb, with its collaterals and branches connecting internally and externally, and its sinews distributed externally.

Comprehensive Functions of the Eight Extraordinary Vessels

The eight extraordinary vessels hold a very important position in the meridian system, providing extensive connections to the twelve main channels, collaterals, and other vessels, and play a leading role in regulating the abundance and deficiency of qi and blood throughout the body. The following outlines their comprehensive functions:

1. Communication and Connection

The eight extraordinary vessels mostly branch from the twelve main channels, and during their distribution, they intersect with other channels, establishing connections between the various meridians. For example, the Yangwei vessel connects all yang channels at the Du vessel’s Fengfu and Yamen points; the Yinwei vessel connects all yin channels at the Ren vessel’s Tiantu and Lianquan points. The three yang channels of the hand converge at the Du vessel’s Dazhui point; the three yin channels of the foot converge at the Ren vessel’s Guanyuan and Zhongji points. The Du, Ren, and Chong vessels also communicate with each other, and the Chong vessel is connected to the Foot Shaoyin and Foot Yangming channels, referred to as the sea of twelve channels; the Dai vessel encircles the waist, linking the various longitudinal channels of the trunk. All of these illustrate that the eight extraordinary vessels play various connecting roles with the twelve channels and related organs.

2. Leadership and Dominance

The eight extraordinary vessels group together meridians with similar properties and functions, exerting leadership and dominance. The Du vessel is known as the “sea of meridians” and the “sea of yang channels,” while the Ren vessel is known as the “sea of yin channels,” and the Chong vessel is referred to as the “sea of twelve channels” and the “sea of blood,” indicating this function. Since the Du vessel is the convergence of all yang channels and is closely related to the Kidney, Brain, and Liver channels, its function is to lead yang qi and true essence. The Ren vessel has the function of nourishing and regulating the qi of the yin channels, as qi is considered yang and blood is considered yin in the human body. Women’s conditions related to pregnancy, childbirth, menstruation, and the Dai vessel are closely associated with blood, hence the saying “Ren governs the womb,” indicating the Ren vessel’s leading and governing role over the yin channels. The Chong vessel originates from the lower abdomen and has close relationships with the twelve main channels and the five zang organs, thus also referred to as the “sea of twelve channels” and the “sea of the five zang organs and six fu organs.” The Du vessel governs the body’s yang qi, while the Ren vessel governs the body’s yin qi, both having significant impacts on the five zang organs and six fu organs, as well as the twelve main channels. The Dai vessel restrains the various channels of the body and regulates their qi. The Yinwei vessel governs the yin channels on both sides of the body, while the Yangwei vessel governs the yang channels, coordinating the yin and yang channels distributed on the inner and outer sides of the lower limbs. The Yin and Yangqiao vessels have the function of “linking” and “connecting” the yin and yang channels of the body, with the Yangwei vessel governing the exterior and the Yinwei vessel governing the interior. The eight extraordinary vessels primarily exert their leadership and dominance through their combination with the twelve main channels.

3. Regulation and Distribution

The eight extraordinary vessels crisscross and circulate among the twelve main channels. When the qi of the twelve main channels and organs is abundant, the eight extraordinary vessels can store it; when the physiological functions of the twelve main channels require it, the eight extraordinary vessels can also distribute and supply it. Therefore, the eight extraordinary vessels play a role in regulating and storing the qi of the main channels. The “Nanjing: Difficulties” once used the relationship between lakes and rivers as a metaphor: “It is like a sage who designs canals; when the canals overflow, they flow into deep lakes, thus the sage cannot confine the flow. When the meridians are abundant, they enter the eight vessels but do not encircle, hence the twelve channels cannot be confined either.” The “Suwen: Atrophy” states: “The Chong vessel is like the sea of the meridians, governing the distribution of qi and blood in the valleys.” Valleys refer to the acupoints between muscles, indicating the Chong vessel’s important role in distributing qi and blood throughout the body. Li Shizhen’s “Study of the Eight Extraordinary Vessels” also states: “The overflowing qi enters the extraordinary vessels, mutually irrigating, warming the organs internally and moistening the pores externally,” which illustrates the extraordinary vessels’ role in regulating and distributing the qi and blood of the twelve channels to the surrounding tissues. The Ren and Chong vessels can also contain kidney qi; the “Neijing” discusses that when kidney qi is abundant, “the Ren vessel is open, and the Chong vessel is abundant, leading to timely menstruation; when blood and qi are abundant, the skin becomes warm, and when blood is solely abundant, it moistens the skin and promotes hair growth.” The Chong vessel ascends to “distribute to the yang” and “irrigate the essence,” while descending to “distribute to the three yin” and “various collaterals,” and the Yinwei and Yangwei vessels can “irrigate the various channels,” all indicating the extraordinary vessels’ role in regulating and distributing qi and blood.

☞Zhang’s Warming Yang Meridian Moxibustion Therapy… A New Choice for Health

☞Dao, Method, Technique, What Level is Your Tuina Skill? (A Must-Read for Practitioners of TCM Tuina)

☞Supplementary Method for Weight Loss: Professional Techniques You Didn’t Know (First Public Release)

☞Feedback on Supplementary Method for Weight Loss in One Week (With Pictures and Truth)

☞Effective Health Preserving Medicinal Wine from Renowned Old TCM Practitioners’ Decades of Clinical Experience (Collector’s Edition)

☞Using Xiao Chai Hu Well, No Need to Find a Doctor (In-Depth Good Article)!

☞Complete Knowledge of Moxibustion! Collect and Read Slowly!

☞TCM Essentials | Do You Really Understand Huang Yuanyu’s Theory of Yin and Yang?

☞Anime Version of “Shang Han Lun” with Gui Zhi Decoction (Including the Text Version of the Timeless Recipe Gui Zhi Decoction)

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Liver Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Lung Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Spleen Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Heart Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Techniques Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section 2

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section 3

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section 4

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section 5

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Kidney Section 6

☞Restoring the Basics of Healing by Hand: Section 7

☞Why Are Chronic Diseases Increasing? Health Preservation is Not Consumption, But Life Extension!

☞Supplementary Method for Weight Loss: The Healthiest and Most TCM-Compliant Weight Loss Technique (Essence Version)

The article is sourced from the internet; if there is any infringement, please contact us for deletion.

If you find it useful, please give a thumbs up at the bottom!