The meridians are a collective term for the jingmai (经脉) and luomai (络脉). They serve as pathways for the circulation of qi (气) and blood (血) in the human body, connecting the organs (脏腑) and facilitating communication between the internal and external environments, as well as traversing vertically and horizontally throughout the body.

The functions of the human meridian system can be summarized in four main aspects, which I will briefly introduce to help everyone gain a better understanding of the meridians.

First, they facilitate the circulation of qi and blood, balancing yin and yang. “The jingmai are the pathways for the movement of qi and blood, nourishing yin and yang, moistening the muscles and bones, and benefiting the joints.” This means that the meridians transport qi and blood to all parts of the body, nourishing both the surface and the internal organs, thus ensuring that the body’s physiological functions are coordinated and maintaining normal life activities. Additionally, because the meridians “internally connect to the organs and externally link to the limbs and joints,” they allow qi and blood to flow through the body in a multi-layered manner, maintaining the yin-yang balance of the internal and external environments.

Second, they resist pathogenic factors and reflect pain. The human meridian system is a multi-layered circulatory and regulatory system that has the function of resisting pathogens and reflecting pain. When there is an imbalance among the organs, qi and blood, and yin and yang, it can lead to pathological changes in the body. The symptoms of these changes will be reflected on the surface of the body through the meridians, causing the patient to experience tenderness or pain in specific areas, along with abnormal subcutaneous tissue, color changes, and temperature variations. Generally, when qi and blood are obstructed, it leads to pain and swelling in related surface areas. When qi and blood stagnate and transform into heat, the body may exhibit redness, swelling, and heat pain, which are manifestations of excess in the meridians. Conversely, when there is insufficient circulation of qi and blood, local numbness or diminished organ function may occur, indicating deficiency in the meridians. If there is insufficient yin qi, the meridians may lack nourishment, leading to sensations of coldness in specific areas or throughout the body, which is a manifestation of yang deficiency in the meridians. If there is insufficient nourishment or blood while yang qi is excessive, symptoms such as restlessness, heat sensations, and fever may arise.

Third, they connect the organs and facilitate communication between the internal and external environments. The jingmai, jingbie (经别), and the eight extraordinary vessels (奇经八脉) and fifteen luomai (络脉) interconnect, entering and exiting the body, linking various organ systems. The tendons and skin connect the muscles and skin of the limbs, while the superficial and subsidiary meridians connect the finer parts of the body. Thus, the meridians integrate the body into an organic whole. The communication function of the meridians is also reflected in their ability to conduct signals. When the body surface senses pathogens and various stimuli, these can be transmitted to the organs. Conversely, when the physiological functions of the organs are abnormal, this can also be reflected on the body surface.

Fourth, they conduct sensations and adjust deficiency and excess. “To examine and adjust qi, one must understand the pathways of the meridians.” This means that when using acupuncture and other therapies, one must carefully regulate the qi mechanism and understand the pathways of the meridians. When acupuncture stimulates acupoints and produces sensations of soreness or distension, this is referred to as “obtaining qi.” When the sensation of qi travels along the meridian pathways during acupuncture, this is called “conducting qi.” The terms “obtaining qi” and “conducting qi” both reflect the conductive and responsive functions of the meridians. Under normal physiological conditions, the meridians can circulate qi and blood, coordinate yin and yang, and maintain life activities.

In summary, the meridians are the channels for the circulation of qi and blood in the body, capable of adjusting the internal yin-yang balance and governing life. Therefore, to ensure health and longevity, one must regularly maintain the meridians, regulate yin and yang, and smooth the flow of qi and blood.

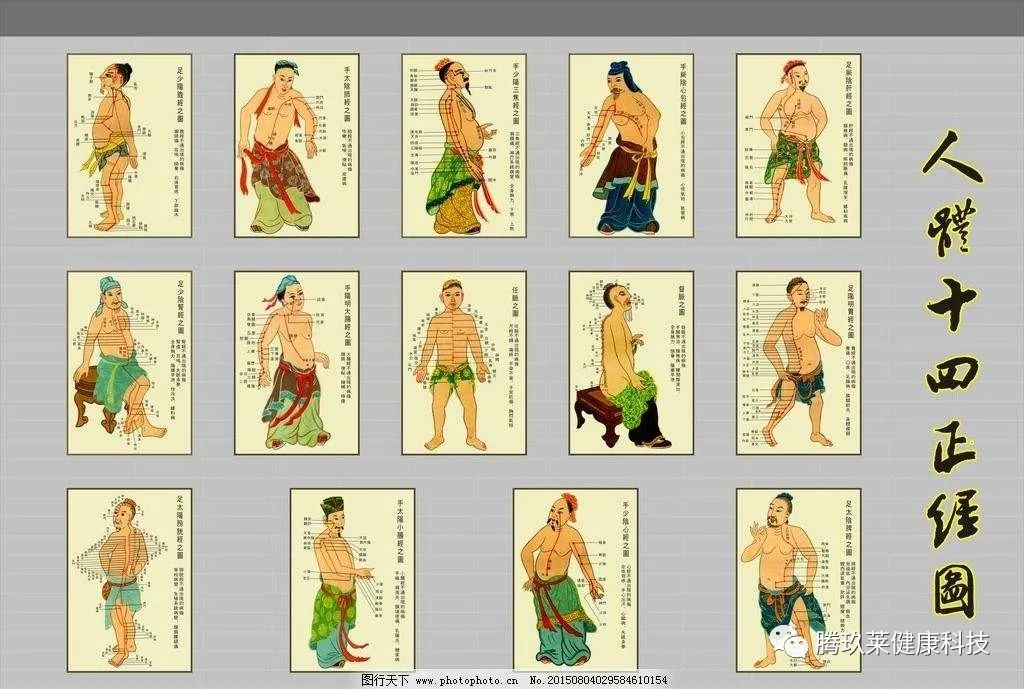

The meridians are a collective term for the jingmai and luomai, serving as pathways for the circulation of qi and blood, connecting the organs, facilitating communication between the internal and external environments, and traversing vertically and horizontally throughout the body. The meridian system is primarily composed of jingmai, with luomai as branches.

1. The luomai include fifteen luomai and countless superficial and subsidiary luomai. The jingmai include twelve jingmai, eight extraordinary vessels, and their associated twelve jingbie and twelve jingjin (经筋).

2. The jingmai and luomai are like latitude and longitude lines, encircling the body and serving as pathways for the circulation of qi and blood, regulating yin and yang, and resisting external pathogens. At the same time, the meridians also exhibit characteristics of reflecting symptoms.

3. The jingmai are the main pathways, while the luomai are the branches. The meridians connect the body’s various tissues and organs into a cohesive whole, linking them into an organic system. Through the activity of the meridian qi, they regulate the functions of all parts of the body, coordinating qi and blood and balancing yin and yang, thus maintaining overall harmony and relative balance in the body.

The theory of meridians is an important component of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Whether in acupuncture or clinical diagnosis and treatment, it is especially reliant on the guidance of meridian theory.

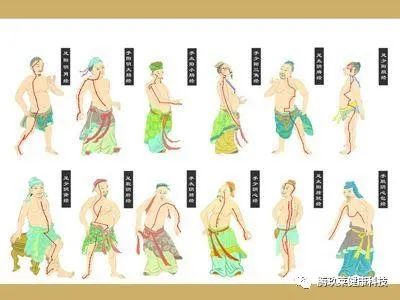

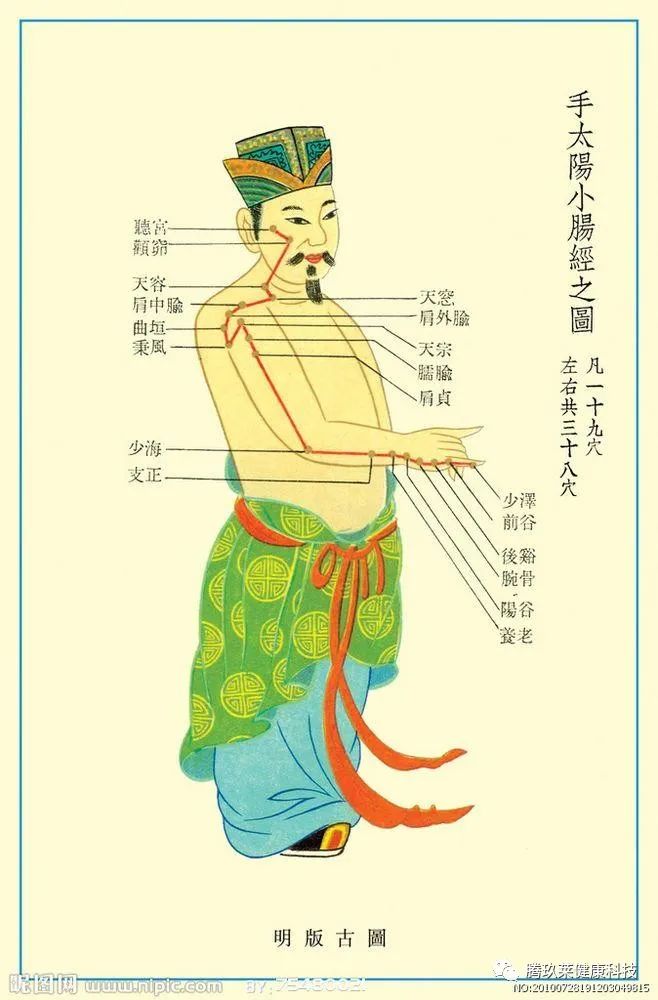

The twelve meridians are each connected to twelve organs in the body, and thus these meridians are named after the organs they connect.

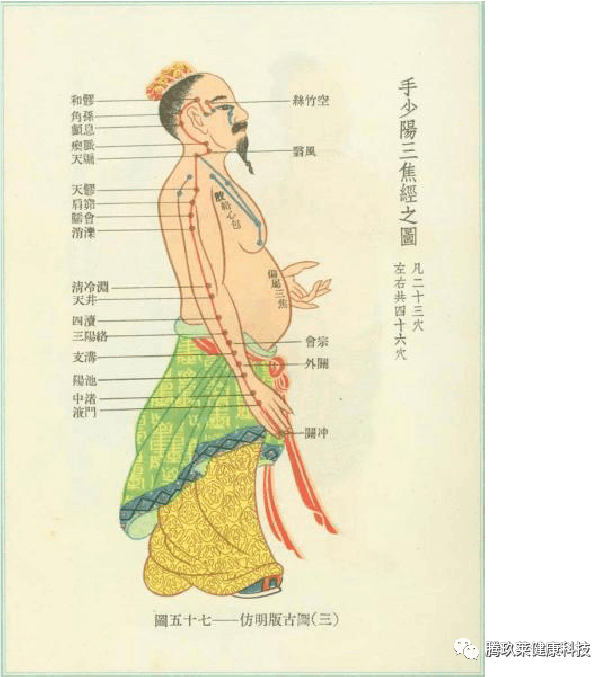

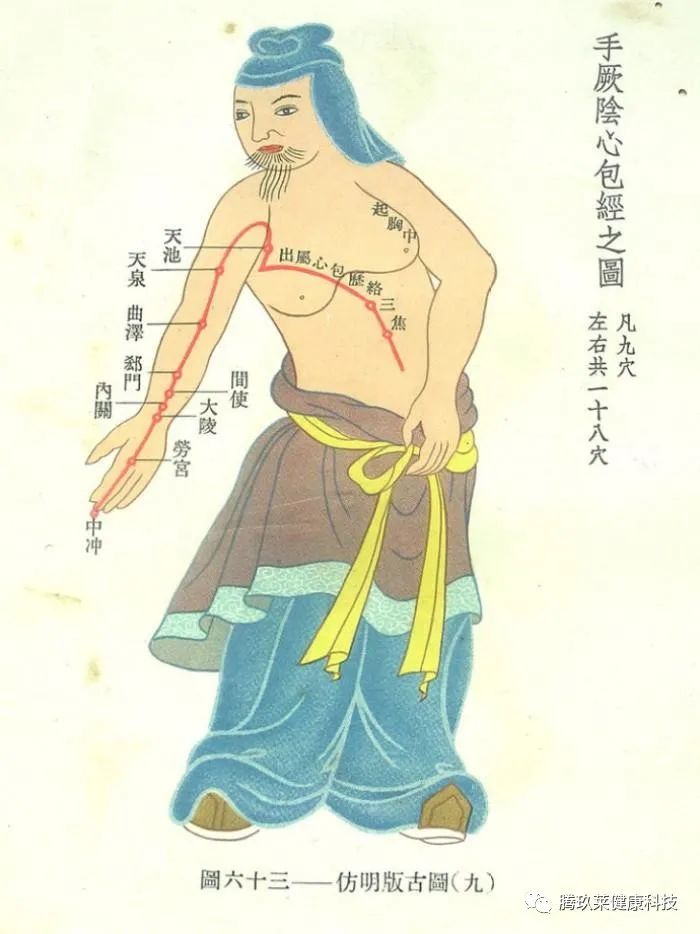

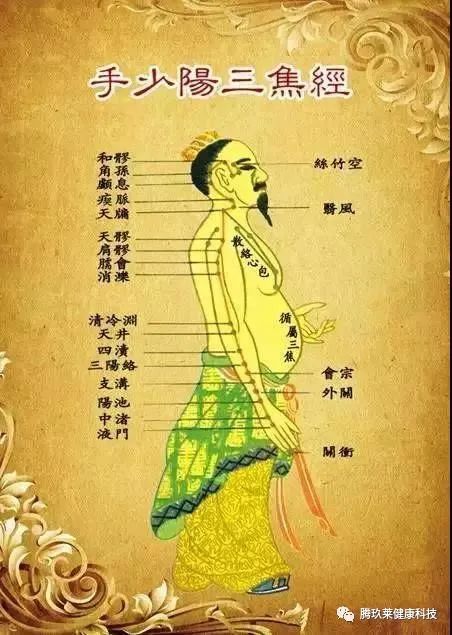

Among them, the Sanjiao (三焦) refers to the entire chest and abdomen, while the Pericardium (心包) is a protective area for the heart, serving as a barrier for the heart, and the others are relatively easy to understand. Remembering the names of these twelve organs is very important; if there is discomfort in any part of the body, one can check which meridian passes through that area, and the corresponding organ will be identified.

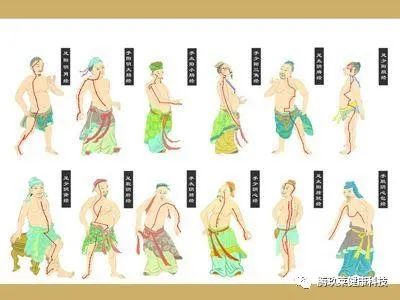

From the arrangement of the twelve meridians, they are divided into two groups: one group is categorized by the hands and feet, while the other is categorized by yin and yang.

The categorization by hands and feet indicates that there are six meridians on the hands and six on the feet and legs.

The categorization by yin and yang indicates that there are three yin meridians on the inner side of the arms and legs, and three yang meridians on the outer side of the arms and legs.

What do Shaoyin (少阴), Jueyin (厥阴), Taiyin (太阴), Yangming (阳明), Shaoyang (少阳), and Taiyang (太阳) represent? They represent the intensity of yin qi and the strength of yang qi.

Shaoyin has the heaviest yin qi, so it is positioned deepest on the inner sides of the arms and legs.

Jueyin has lighter yin qi than Shaoyin but heavier than Taiyin, so it is positioned in the middle.

Taiyin has the lightest yin qi, thus it is positioned on the outermost layer.

Yangming has the most abundant yang qi, akin to the midday sun, so it is positioned on the outermost sides of the arms and legs.

Shaoyang has slightly weaker yang qi than Yangming, similar to the sun in the morning, so it is positioned in the middle of the outer sides.

Taiyang has weaker yang qi than Shaoyang, akin to the first light of dawn, thus it is positioned on the innermost side of the outer layer.

Why did our ancestors subdivide yin and yang to such an extent? It is to remind you to pay attention to the balance of yin and yang when using the meridians. This balance of yin and yang includes the balance between the meridians themselves, the balance between the body and the meridians, and the balance between the meridians and nature. The balance between the body and the meridians requires you to choose meridians based on the strength of your body. For example, if the body is weak, it is best to first choose yang meridians for massage to replenish the righteous qi, while yin meridians should be approached only after the righteous qi has been replenished; if the body is strong, both yin and yang meridians can be massaged.

The balance of yin and yang in relation to nature is related to the temperature of the four seasons. In summer, when yang qi is most vigorous, even individuals with weak bodies can benefit from smoothing the yin meridians. The theory of yin-yang balance can also be applied to the techniques used in massage; for instance, the massage of yin meridians is best done with a reinforcing technique, while the massage of yang meridians can use a reducing technique.

Reinforcing and Reducing Techniques in Massage

Generally, massaging along the meridian is considered reinforcing, while massaging against the meridian is considered reducing.

A gentle massage is reinforcing, while a strong massage is reducing.

A short duration of massage is reinforcing, while a long duration is reducing.

A small area of massage is reinforcing, while a large area is reducing.

Do you remember the more than three hundred acupoints?

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, there is a saying during meridian massage called “using pain as a guide,” meaning that the painful area is the acupoint to be massaged. For example, if you know you have a heart condition, you can slowly press along the corresponding Heart Meridian (心经) and Pericardium Meridian (心包经), feeling the sensations along the entire meridian. If some areas feel sore, some feel sharp pain, some feel numbness, and some feel distended or swollen, then the focus of your treatment should be on the most painful area, kneading and dispersing the pathological site. Some external medications can also be used; the more pronounced the pain, the more you should persist in stimulating that area, and your body’s condition will improve quickly.

Some people may know they have heart issues, but when pressing on these two meridians, they do not feel significant pain. In this case, you should check both arms, as the meridians in the body are symmetrical and consistent. However, when there is a disease, the responses of the left and right meridians may not be identical; the area with more pronounced pain indicates where the disease is more pronounced, which also shows that the qi and blood in that meridian are insufficient and the response is slow. In this case, treatment should focus on dietary therapy first to replenish qi and blood, while also gently palpating along that meridian to check for any hard lumps, excess tissue, or slight protrusions compared to other areas, and then focus on kneading that area. If you merely memorize all the acupoints without paying attention to the most painful point, the treatment effect will not be good.

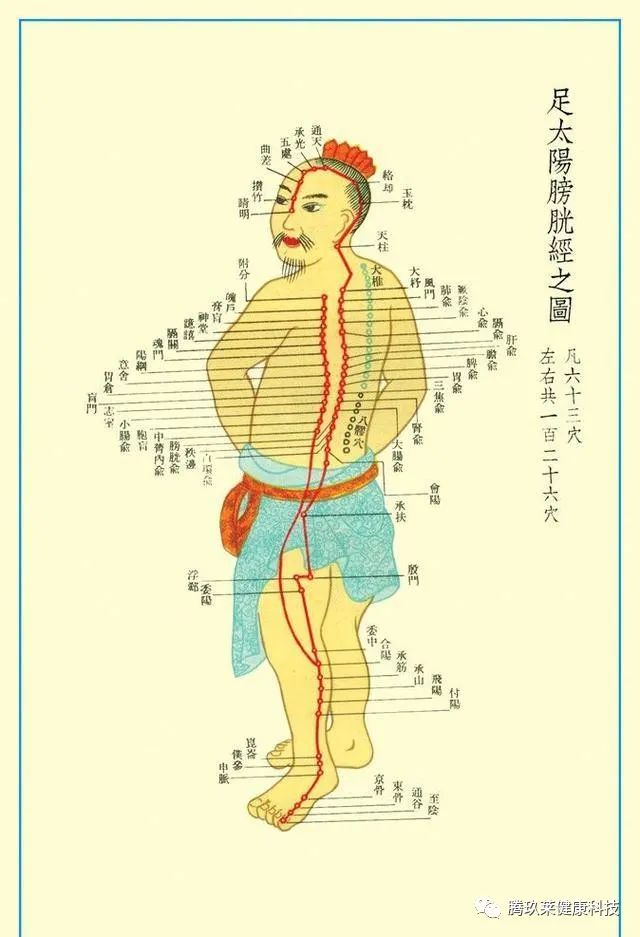

Let’s start with the most commonly used Bladder Meridian (足太阳膀胱经), as it has the most abundant yang qi and the broadest treatment range, making it the most frequently used meridian. The Bladder Meridian begins at the Jingming point (睛明穴) at the inner corner of the eye, ascends over the forehead to the top of the head, travels down the back of the neck, the back, the outer side of the thigh, the back of the calf, and ends at the Zhiyin point (至阴穴) at the outer side of the little toe. It has a total of 67 acupoints, making it the longest meridian with the most acupoints in the body.

When the Bladder Meridian reaches the Zhiyin point at the foot, its flow does not stop but continues through the little toe, ascending from the Yongquan point (涌泉穴) at the center of the foot. At this point, the meridian acquires a new name—the Kidney Meridian (足少阴肾经).

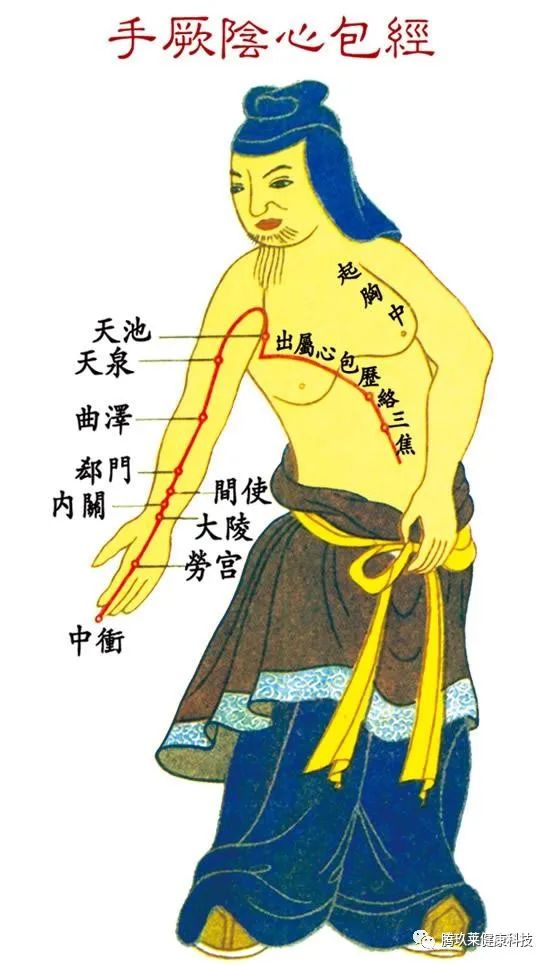

The Kidney Meridian starts beneath the little toe, slants towards the center of the foot, ascends along the inner edge of the lower limb, passes through the abdomen, reaches the chest, and connects with the next meridian, the Pericardium Meridian (手厥阴心包经).

Key Points for Palpation of the Twelve Meridians

Lung Meridian: Feishu (肺俞), Zhongfu (中府), Kongzui (孔最), Gaohuang (膏盲), Chize (尺泽).

When the Lung Meridian has excess heat, there is tenderness 0.5 cun lateral to the spinous processes of T1-T3, and tenderness is also present at the Shanzhong (膻中) and Daju (大巨) points. When the qi of the Lung Meridian is obstructed, there is tenderness at the Shanzhong point. In cases of Lung Meridian deficiency and cold, there is a sensation of heaviness at the Fengmen (风门) and Dazhu (大杼) points. For hemoptysis or hematochezia, there may be tenderness at the Kongzui point or a sensation of heaviness when pressed. When the qi is deficient, the Gaohuang point may appear swollen or elastic, with low skin temperature.

Large Intestine Meridian: Dazhu (大肠俞), Tianzhu (天抠), Wenliu (温溜), Quchi (曲池), Hegu (合谷).

When the qi of the Large Intestine Meridian has excess heat or there is an obstruction in excretion, there may be tenderness at the Quchi, Feishu, Tianzhu, and Qizhu (骑竹马) points. When the qi is stagnant, there may be tenderness at the Daju point. In cases of enteritis, there is significant tenderness at the Shousanli (手三里), Shangjuxu (上巨虚), and Tianzhu points, with skin temperature higher than adjacent points. In chronic enteritis, the skin temperature may be lower, with a sensation of quickness upon touch.

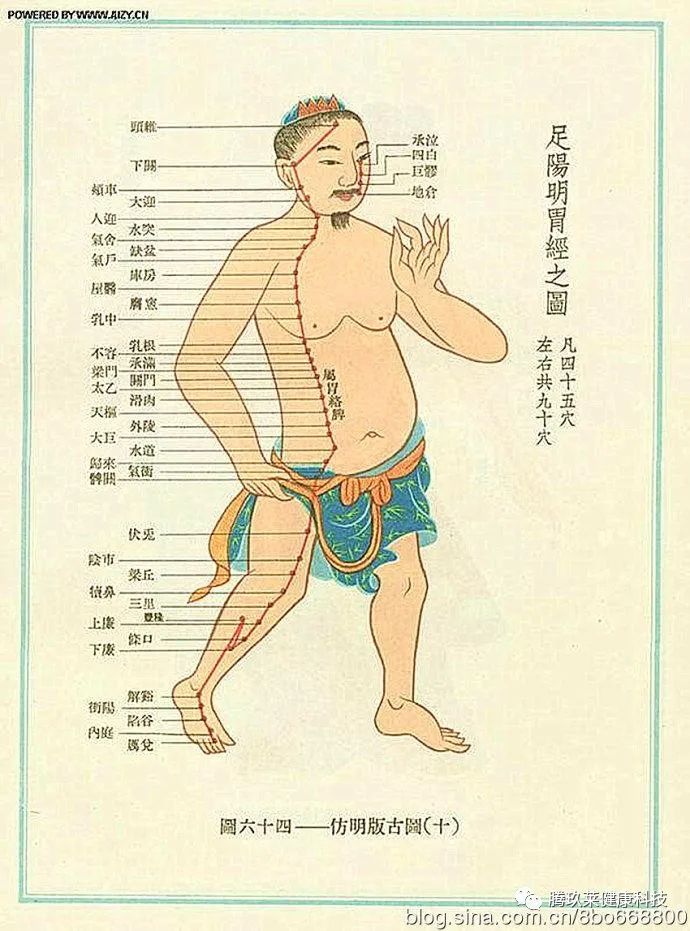

Stomach Meridian: Weishu (胃俞), Zhongyuan (中院), Liangqiu (梁丘), Zusanli (足三里), Fenglong (丰隆).

When the Stomach Meridian has excess heat, there may be tenderness at the Zhongyuan and Liangqiu points. In cases of excessive gastric acid, there may be tenderness at the Jueque (巨阙) and Burong (不容) points. When the Stomach Meridian is deficient and cold, pressing the Zhongwan (中脘) and Zusanli points may feel comfortable. For gastric ulcers, tenderness may be present at the Weishu point and its lateral side, with tenderness radiating down to below the knee. In cases of severe stomach pain, there is significant tenderness at the Tianzong (天宗) point, which can relieve pain when pressed.

Spleen Meridian: Pishu (脾俞), Zhangmen (章门), Diji (地机), Dabao (大包), Pishu (脾俞).

In cases of indigestion or dysfunction of transformation, there may be tenderness at the Pishu, Zhangmen, and Dabao points. When blood circulation is unbalanced, the Pishu point may feel tense or tender. In cases of Spleen heat or qi stagnation, there may be significant tenderness at the Diji point. When the Spleen is deficient and causes distension, pressing the Pishu point may feel sore or the skin temperature may be low.

Heart Meridian: Xinshu (心俞), Jueque (巨阙), Yinxin (阴郄), Shaohai (少海).

When the Heart Meridian has excess fire, there may be tenderness on the inner side of the Xinshu point. In cases of heart valve disease, the Jueque point may feel swollen, and there may be sensitive points from the Xinshu point to the Gaohuang point. When the qi is deficient or the function is low, there may be tenderness at the Sanyinjiao (三阴交), Shuifen (水分), and Xinshu points.

Small Intestine Meridian: Xiaoshu (小肠俞), Guanyuan (关元), Yanglao (养老), Xiaohai (小海), Xiagu (下巨虚).

For Small Intestine Meridian diseases, there may be reactions at the Guanyuan and Yanglao points. When invaded by wind and cold, there may be tenderness at the Tianzong, Fengmen, and Xiaohai points. If the Small Intestine Meridian disease shifts to the Heart Meridian, pressing the Guanyuan point is effective. For shoulder pain caused by Small Intestine Meridian qi obstruction, there may be tenderness at the Xiagu point, which is effective when needled. For low back pain in the Xiaoshu area, there may be significant tenderness at the Yanglao point, which is effective when needled.

Bladder Meridian: Pangguangshu (膀胱俞), Zhongji (中极), Jinmen (金门), Weizhong (委中), Kunlun (昆仑), Tianzhu (天拄), Bailiao (八髎).

When the qi of the Bladder Meridian has excess heat, the Weizhong point may feel warm, and the luomai may be full. In cases of damp-heat descending and qi obstruction, there may be tenderness at the Zhongji, Jinmen, and Pangguangshu points. When invaded by wind and cold, there may be tenderness at the Tianzhu, Bailiao, and Chengshan (承山) points. When the qi is deficient, pressing the Zhongji and Pangguangshu points may feel pleasant.

Kidney Meridian: Shenfu (肾俞), Jingmen (京门), Shuizuan (水泉), Shuifen (水分), Huangshu (肓俞).

For Kidney Meridian diseases, there may be tenderness at the Shuizuan, Shuifen, and Huangshu points. For kidney diseases, there may be tenderness at the Shenfu and Jingmen points. When the kidney’s excretory function is compromised, the Zhukui point may show positive reactions (hardness, tenderness). Therefore, moxibustion at the Zhukui point has detoxifying effects. In cases of urinary system disorders, there may be tenderness at the Bailiao point.

Pericardium Meridian: Jueyinshu (厥阴俞), Shanzhong (膻中), Xiemen (郄门), Daling (大陵).

When emotions are unstable, with unpredictable laughter and crying, there may be significant tenderness at the Shanzhong and Xiemen points. In cases of menstrual irregularities, dysmenorrhea, or lower abdominal blood stasis, there may be tightness or tenderness at the Xiemen point, which can be needled to regulate menstruation and relieve pain. For palpitations, pressing the Jueyinshu and Shanzhong points can provide relief, and moxibustion is also effective.

Sanjiao Meridian: Sanjiao (三焦俞), Shimen (石门), Weiyang (委阳), Huizong (会宗).

When the qi of the Sanjiao Meridian is obstructed, there may be tenderness at the Huizong, Weiyang, and Shimen points. When there is excess heat in the qi, the area around the Sanjiao point may feel tense, and there may be significant tenderness at the Huizong point. In cases of urinary retention, which is due to qi obstruction in the Sanjiao Meridian, the Shimen point may feel distended.

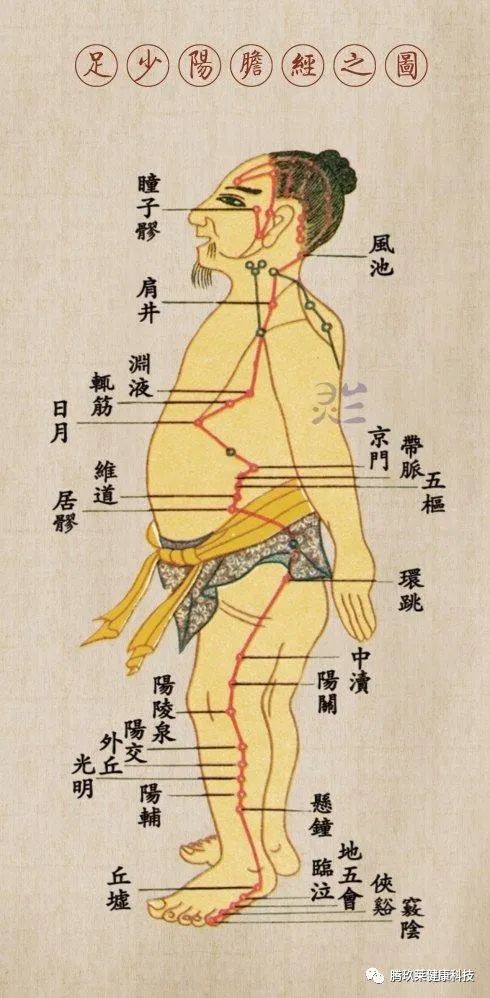

Gallbladder Meridian: Danfu (胆俞), Riyue (日月), Tianzong (天宗), Jing (京), Yanglingquan (阳陵泉), Waiqiu (外丘).

In cases of cholecystitis, there may be tenderness at the Riyue, Jingmen, and Tianzong points. When there is excess heat in the Gallbladder Meridian, the Waiqiu point may feel warm. When the qi is deficient, pressing the Danfu and Riyue points may feel comfortable.

Liver Meridian: Ganfu (肝俞), Qimen (期门), Zhongdu (中都), Ququan (曲泉).

When the qi is stagnant (insomnia, irritability, hypertension), there may be swelling and tenderness at the Ganfu point, and significant tenderness at the Zhongdu point. In cases of hepatitis (excess heat in the qi), there may be an allergic band from two cun above the inner ankle to the Zhongdu point, and sometimes tenderness may also be present at the Yanglingquan and Waiqiu points. For sexual dysfunction, pressing the Ququan point may elicit pain or a sensation of heaviness.

By identifying the affected meridians and acupoints using the above methods, combined with the four diagnostic methods and the eight principles, one can determine the cause, location, and nature of the disease, thus proposing effective treatment plans.

Remembering the relationship between the meridians and acupoints is crucial for treating conditions.

【Scan the QR code to join the group for learning and health!】】

【Scan the QR code to join the group for learning and health!】】