The meridians are the channels through which Qi and blood circulate in the human body according to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) theory, collectively referred to as Jingmai (经脉) and Luomai (络脉). They play a crucial role in connecting the internal and external aspects of the body, linking the upper and lower parts, and integrating the left and right sides, forming a network throughout the body. The deeper, longitudinal, and larger primary vessels are known as Jingmai, while the shallower, transverse, and smaller branch vessels are referred to as Luomai.

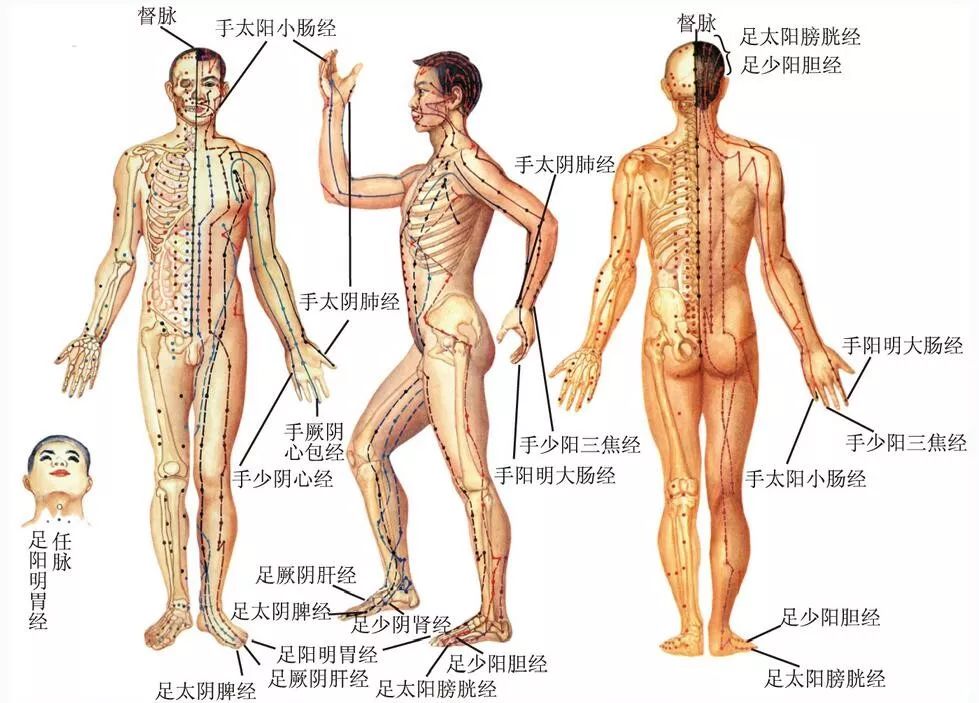

Diagram of the distribution of meridians in the body (front, side, back)

Meridian System

The Jingmai, also known as Zhengjing (正经), includes the twelve primary meridians, twelve collateral meridians, and the eight extraordinary meridians. The Luomai, also known as Bie Luo (别络), consists of the larger fifteen collateral meridians and their smaller branches, known as Sun Luo (孙络); the tiny branches that appear on the body surface are called Fu Luo (浮络). Based on the distribution of Qi and blood flow in the twelve primary meridians, the body’s muscles are divided into twelve groups, known as the Twelve Jingjin (十二经筋); the skin is divided into twelve regions, known as the Twelve Pibu (十二皮部). Thus, the meridian system is composed of Jingmai, Luomai, Jingjin, and Pibu (see diagram). The meridian system is an important aspect of TCM that explains the functional structure of the human body. It connects the internal and external aspects, where diseases affecting the external meridian system can directly influence the related internal organs; conversely, diseases in the internal organs will inevitably reflect on the corresponding meridians. The organs are the source of the generation of Qi and blood, while the meridians are the pathways for their circulation; these two aspects are an inseparable whole. As stated in the Suwen (素问) “On Regulating the Meridians”: “The pathways of the five organs all emerge from the Jing and Luo (meridians) to circulate Qi and blood. When Qi and blood are not harmonious, various diseases arise; therefore, one must guard the Jing and Luo.” Thus, the meridians can “determine life and death, address various diseases, and regulate deficiency and excess, and must not be obstructed” (Lingshu, 灵枢·经脉).

Meridian Theory

Meridian theory specifically studies the composition, distribution, physiological functions, pathological changes of the human meridian system, and guides clinical treatments in various disciplines of TCM. It is an essential component of the foundational theories of traditional Chinese medicine. Particularly, acupuncture and Tui Na (推拿) therapies directly act on the meridian system, making meridian theory the theoretical basis for acupuncture and Tui Na. The clinical treatment of diseases in TCM involves discerning the pathological changes in the organs and meridians, understanding the transmission of diseases, and the theory of herbal formulas corresponding to the meridians, all based on meridian theory. The Lingshu states: “The twelve primary meridians are the basis of life, the cause of diseases, the means of treatment, and the origin of illness; they are the beginning of learning and the end of practice. The coarse is easy, while the fine is difficult.” In the Song Dynasty, Dou Cai stated, “To study medicine without knowing the meridians is to err as soon as one opens their mouth and acts” (Bian Que Xin Shu, 《扁鹊心书》).

According to existing literature, the earliest recorded work on meridian theory is the “Silk Manuscript on Meridians” (《帛书·经脉》) unearthed from the Han tomb at Mawangdui in Changsha, Hunan, in 1973. According to the research team that organized the silk manuscripts, this text was likely copied around the Qin and Han dynasties, divided into two volumes, documenting the naming, distribution, symptoms, and moxibustion treatment of eleven ancient meridians. Due to differences in naming, the team temporarily named the two volumes “The Moxibustion Classics of the Eleven Meridians of the Feet and Arms” and “The Moxibustion Classics of the Yin and Yang Eleven Meridians,” later included in the “Fifty-Two Disease Formulas” (1978). By the time the “Neijing” (《内经》) was compiled, the foundational theories of traditional medicine had gradually formed, and meridian theory had developed to a relatively mature stage. The “Lingshu” contains specialized chapters on “Meridians,” “Collaterals,” “Tendons,” and “Fluid of Meridians”; the “Suwen” includes chapters on “Meridian Theory,” “Skin Regions,” and “Meridian Collaterals.” This not only developed the eleven meridians into twelve but also modified and supplemented the naming, distribution, symptoms, and treatment content of each meridian, establishing a relationship with the organs, forming a continuous flow process of Yin and Yang. It also documented the twelve collaterals derived from the twelve primary meridians, the fifteen collateral meridians, and the eight extraordinary meridians scattered throughout various chapters, incorporating the twelve tendons and twelve skin regions into the meridian system. Furthermore, most chapters in the “Neijing” contain content on meridians, becoming a classic of meridian theory. The Han Dynasty’s “Nanjing” (《难经》) provided detailed explanations of eighty-one difficult questions related to meridians, supplementing and developing the meridian theories and practices of the “Neijing,” and for the first time introduced the “Eight Extraordinary Meridians,” becoming a classic on par with the “Neijing.” The Jin Dynasty’s Wang Shuhe’s “Pulse Classic” marked the development of meridian theory in diagnostics, becoming the earliest traditional medical diagnostic monograph. At the same time, Huangfu Mi’s “The Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion” compiled the academic developments of acupuncture before the Jin Dynasty, integrating the “Lingshu” (referred to as the “Acupuncture Classic”), nine volumes of the “Suwen,” and the now-lost “Mingtang Kongxue Acupuncture Treatment Essentials” into one book. This work represents a mature stage of the development of meridian theory guiding clinical acupuncture practice. The number of acupuncture points has increased from over 160 recorded in the “Neijing” to 349, detailing the location, indications, needling techniques, and moxibustion methods for each point, especially providing formulas for acupuncture treatment of various diseases. The Tang Dynasty’s Yang Shangshan’s “Huangdi Neijing Taisu” organized acupuncture points based on the twelve meridians. Sun Simiao’s preface to the “Qianjin Yaofang” mentions that at that time, illustrated meridian charts had already been published, though they have unfortunately been lost. In the fifth year of the Northern Song Dynasty (1027), Wang Weiyi was commissioned to re-examine the meridians and acupuncture points, compiling the “Copper Man Acupuncture Point Diagram” and casting two bronze figures (see acupuncture bronze figures), striving for the unification and standardization of meridians and acupuncture points, contributing to the development of meridian studies. The Southern Song’s Wang Zhizhong’s “Acupuncture for Life” systematically organized the methods of point selection and formulas. The Jin Dynasty’s Dou Mo’s “Guide to Acupuncture” advocated the Eight Methods of the Spirit Turtle. He Ruo Yu’s “Flowing Qi and Subtle Points” was annotated by Yan Mingguang, resulting in the “Ziwu Liuzhu Acupuncture Classic,” establishing a unique method of point selection based on time (see Ziwu Liuzhu Acupuncture Method). The Yuan Dynasty’s Hua Shou’s “Elaboration on the Fourteen Meridians” re-examined the meridians and acupuncture points, making many supplements. The Ming Dynasty’s Gao Wu’s “Collection of Acupuncture Essentials” comprehensively organized the indications and methods of point selection, while Li Shizhen compiled the “Study of the Eight Extraordinary Meridians,” achieving a relatively complete understanding of the distribution, corresponding acupuncture points, and symptoms of the Eight Extraordinary Meridians. By this point, meridian theory had developed to a relatively complete stage. Subsequently, Yang Jizhou summarized the academic achievements of acupuncture before the Ming Dynasty, compiling the “Great Compendium of Acupuncture,” contributing to the development of meridian theory. After the Qing Dynasty, there were many monographs on meridian studies, such as “Complete Book of Meridians” and “Diagram of Meridians,” which provided some supplements to meridian theory.

Meridian theory, with its unique theoretical value, forms its own system while also interpenetrating and connecting with the theories of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, as well as the organ theory. The meridians and acupuncture points have both temporal and spatial connotations, with Qi and blood circulating through the meridians in a regular manner. The meridians connect with the organs, limbs, and sensory organs, forming a unified whole, thus integrating the physiological functions and pathological changes of the meridian system with the physiology and pathology of the organs, becoming the theoretical core guiding the treatment of various disciplines in TCM.

The diagnostic methods of TCM are macro and holistic, determining the internal changes of the organs based on the external manifestations of the meridians. Observations of various body parts are related to the meridians; facial and skin observations belong to skin region diagnostics, while observations of the sensory organs and tongue must differentiate between deficiency and excess based on the meridians. In the inquiry, whether asking about the onset of the disease (past history), fetal diseases (family history), or current diseases (present history), one must inquire according to the meridians. The manifestations of various diseases must clarify which meridian the affected area belongs to. Palpation is a method to obtain objective indicators of pathological changes, while pulse diagnosis involves palpating the “arteries within the meridians,” that is, feeling the pulse at the surface of the body, such as the pulse at the cun (寸口) (the radial artery at the wrist) belonging to the Hand Taiyin Lung Meridian, and the pulse at the fu (趺阳) (the dorsalis pedis artery) belonging to the Foot Yangming Stomach Meridian. These pulse manifestations belong to the “floating and sinking” of the meridians. For acupuncture and massage practitioners, it is also necessary to palpate the head and face, the Shu and Mu points (chest and abdomen Mu points and back Shu points), and the four extremities (specific acupuncture points below the elbows and knees), which serve as both diagnostic methods and ways to select effective treatment points. The Lingshu states: “For all who use needles, one must first observe the reality and deficiency of the meridians, palpate and follow them, press and bounce them, observe their responses, and only then select and apply them.”

The treatment of all disciplines in TCM is conducted under the guidance of meridian theory. Based on the differentiation of meridians and accurate formulation of treatment principles, physicians using herbal treatments must select herbs that correspond to the meridians to compose formulas; acupuncture and massage practitioners must select points along the meridians to compose formulas and choose appropriate tonifying or reducing techniques according to the meridian’s direction and the condition of deficiency or excess. Qigong and health preservation also rely on the guidance of meridian theory.

Meridian Qi

Refers to the Qi of the meridians. It indicates the functional activities of the meridian system within the human body, originating from the Yuan Qi (元气) bestowed by the parents and the Gu Qi (谷气) generated from the ingestion of food and water. The formulation of acupuncture treatment principles and the selection of techniques are inseparable from the guidance of the theory of meridian Qi. The Lingshu states: “The meridians are the pathways for circulating Qi and blood, nourishing Yin and Yang, moistening the tendons and bones, and benefiting the joints.” Because climatic conditions have periodic seasonal changes over time, the meridians also exhibit periodic fluctuations in the circulation of Qi and blood, reflected in the periodic opening and closing of the acupuncture points, which is the theoretical basis for the Ziwu Liuzhu acupuncture method. In acupuncture treatment, “obtaining Qi” means acquiring meridian Qi at the acupuncture point, “Qi arrives and is effective.” Moreover, it is essential to guide the obtained meridian Qi to the affected area, i.e., “Qi arrives at the disease site,” to achieve the effect of adjusting deficiency and excess. By employing various tonifying and reducing techniques, the body’s comprehensive resistance to disease (Wei Qi, 卫气) can be mobilized, thus curing diseases caused by disharmony of Qi and blood and imbalance of Yin and Yang.

Modern Research

Modern research primarily utilizes scientific and technological methods to explore the characteristics and essence of meridians from different perspectives. Since the 1950s, Chinese researchers have been engaged in morphological studies of meridians, physiological studies, biological studies, embryological studies, biophysical studies, and studies on the sensation and transmission along the meridians, obtaining a wealth of experimental data and information through experiments on humans and various animals. Many hypotheses regarding the essence of meridians have emerged from these studies, such as the peripheral nerve-related theory, connective tissue-related theory, special structure theory, meridian-cortex-viscera correlation theory, third balance system theory, neurohumoral correlation theory, dual reflex hypothesis of meridian essence, intercellular information transmission theory, protein liquid crystal order hypothesis, meridian biological holography theory, and field theory. However, these theories can only partially explain meridian phenomena, and there is still no universally accepted conclusion.