The Six Fu organs include: the Gallbladder (Dan), Stomach (Wei), Small Intestine (Xiao Chang), Large Intestine (Da Chang), Bladder (Pang Guang), and San Jiao (Triple Burner). Their common physiological characteristic is the reception and transformation of food and fluids. In ancient times, the term “Fu” was written as “府”, which means a hollow place for storing items, allowing for both entry and exit. The primary physiological function of the Six Fu organs is “transformation“, indicating that their role is mainly to receive, ripen, digest, and transform food, existing in a continuous cycle of fullness and emptiness. The Six Fu organs do not store essence and qi.

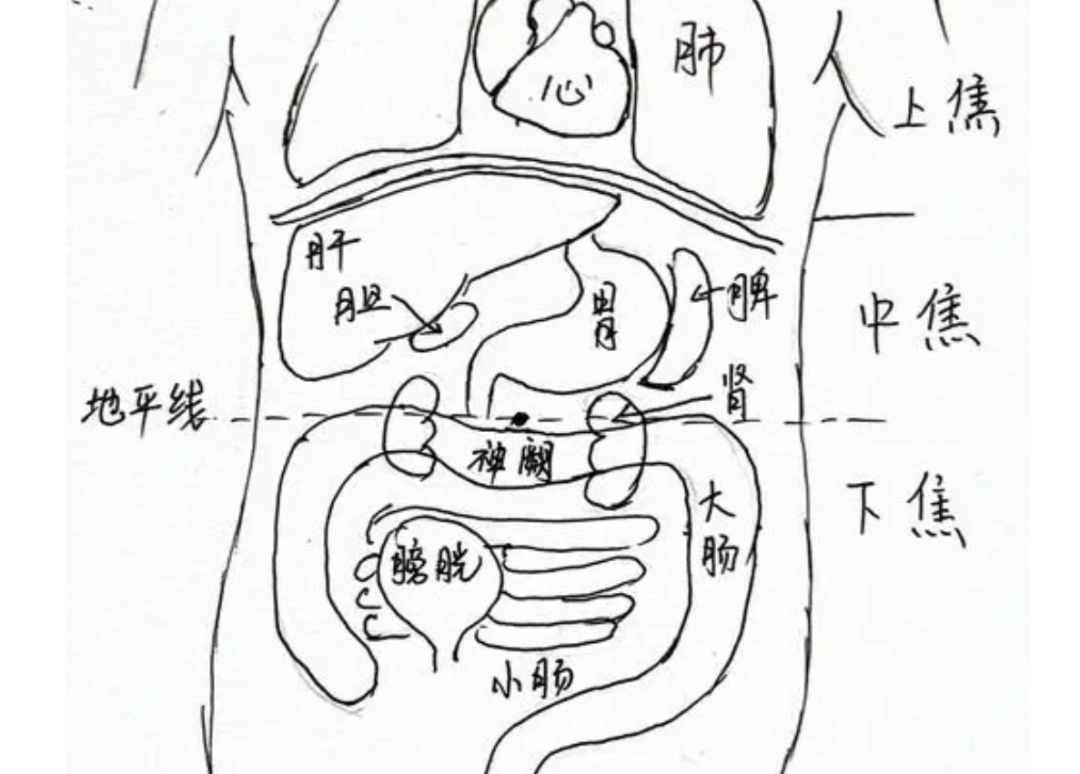

From the moment food enters the body until it is expelled, it must pass through seven important gates, referred to as the “Seven Gates of Passage” in the Nan Jing, namely the lips, teeth, epiglottis, cardia, pylorus, ileocecal valve, and anus. The lips are the “Flying Gate”, indicating that they can open and close freely like a door; the teeth are the “Hinged Door”, which guard the upper end of the digestive tract and chew food; the epiglottis is the “Inhalation Gate”, where the esophagus and trachea meet, serving as the portal for air entering and exiting the body; the cardia is the upper opening of the stomach, where food enters; the pylorus is the lower opening of the stomach, connecting to the small intestine; the ileocecal valve is where the small intestine meets the large intestine, preventing the fine substances from the small intestine from entering the large intestine; the anus, also known as the “Spirit Gate”, is the final part of the digestive tract, allowing for the expulsion of feces. Therefore, any pathological changes at any of the Seven Gates will affect the reception, digestion, absorption, and excretion of food. (1) Gallbladder The gallbladder is attached to the liver and is a hollow sac-like organ. Its main physiological function is to store and excrete bile. Bile is produced in the liver and secreted by it. Once generated, bile flows into the gallbladder for storage. Bile is also known as essence fluid, hence the gallbladder is referred to as the “Palace of Essence”. Bile is yellow-green and extremely bitter, playing a crucial role in digestion. After eating, bile is released into the intestine through the liver’s dispersing action, assisting the spleen and stomach in maintaining normal digestion. Due to the close relationship between the liver and gallbladder, if liver function is normal, bile production and excretion will be smooth, allowing for proper digestion. If the liver is diseased, it will affect bile production and excretion, leading to digestive dysfunction. For example, if gallbladder qi is rebellious, bile may rise, causing a bitter taste in the mouth; if bile excretion is obstructed and cannot smoothly enter the intestine, symptoms such as loss of appetite, abdominal distension, and loose stools may occur; gallbladder disease can also cause nausea and vomiting; if the liver and gallbladder fail to disperse properly, bile may overflow into the skin, resulting in jaundice; if bile stagnates and transforms into heat, damp-heat accumulation can further congeal bile into stones. Although the gallbladder is one of the Six Fu organs, it primarily stores essence fluid and is a clean palace, not directly receiving food waste, which distinguishes it from other Fu organs, thus it is classified as a Extraordinary Fu organ. (2) Stomach The stomach is located below the diaphragm, with its upper opening known as the cardia, connecting to the esophagus, and its lower opening as the pylorus, leading to the small intestine. The stomach is also referred to as the “Stomach Cavity”, divided into three parts: upper, middle, and lower. The upper part is called “Upper Cavity”, including the cardia; the lower part is “Lower Cavity”, including the pylorus; the area between the upper and lower cavities is called “Middle Cavity”, which is the body of the stomach. The main physiological functions of the stomach can be summarized in two aspects: (1) It governs the reception and ripening of food and fluids. Food enters through the mouth, passes through the esophagus, and enters the stomach, which receives it, hence the stomach is also called the “Sea of Food and Fluids”, as the physiological activities of the body and the transformation of qi, blood, and fluids depend on the nutrition from food, thus the stomach is also known as the “Sea of Qi and Blood from Food and Fluids”. Therefore, if the stomach is diseased, it can easily affect its function of receiving food, leading to symptoms such as poor appetite and aversion to food. “Ripening” implies preliminary processing and digestion. Food in the stomach is ground and digested, transforming into chyme, which then moves down to the small intestine for further digestion. The reception and ripening functions of the stomach are integrated with the transportation function of the spleen, referred to as “Stomach Qi”; “Human life is based on Stomach Qi; with Stomach Qi, there is life; without Stomach Qi, there is death”. (2) It governs the downward movement, promoting harmony. After food enters the stomach and undergoes ripening, it moves into the small intestine for further digestion and absorption, with the turbid parts descending into the large intestine to form feces for excretion. Thus, the stomach governs downward movement, promoting harmony. The downward movement of turbid substances is a prerequisite for the stomach to continue receiving food. If the stomach does not harmonize and descend, food may stagnate in the stomach, leading to symptoms such as distension and pain in the stomach area, and aversion to food. If Stomach Qi is rebellious, it can cause nausea, vomiting, belching, and hiccups. Additionally, if Stomach Qi does not descend, it will also affect the spleen’s function of ascending clear qi. (3) Small Intestine The small intestine is located in the abdomen, connecting above to the pylorus and below to the ileocecal valve, where it meets the large intestine. The physiological functions of the small intestine can be summarized in two aspects: (1) Reception and storage of food. Reception refers to the organ’s ability to hold food, meaning the small intestine receives the partially digested food from the stomach, thus serving as a container for the stomach’s contents. Food remains in the small intestine for a longer duration to facilitate further digestion, allowing the food to transform into essence to nourish the entire body. If the small intestine’s function of receiving food is impaired, it can lead to digestive and absorption issues, manifesting as abdominal distension, diarrhea, and loose stools. The function of transformation refers to the changes, digestion, and transformation of food; the small intestine’s transformation function is to further digest and absorb the food that has been partially digested by the stomach. (2) Separation of clear and turbid. The “clear” refers to various essence substances, while the “turbid” refers to the residual waste left after digestion. The small intestine’s function of separating clear from turbid specifically includes three aspects: first, it separates the digested food into two parts: essence and waste; second, it absorbs the essence of food and transports the waste to the large intestine; third, while absorbing the essence of food, the small intestine also absorbs a large amount of fluids, which are then excreted into the bladder as urine. Thus, the physiological function of the small intestine is crucial in the digestion of food. When the small intestine functions normally, the clear and turbid substances follow their respective pathways, with essence distributed throughout the body and waste descending to the large intestine, while excess fluids are excreted into the bladder. If the small intestine is diseased, it can not only cause digestive dysfunction, leading to symptoms such as abdominal distension and pain, but also affect the excretion of urine and feces, for example, leading to reduced urination and loose stools. In such cases, the method of separating and benefiting is often employed, known as “promoting urination to solidify stools”. (4) Large Intestine The large intestine is also located in the abdomen, connecting above to the small intestine at the ileocecal valve, with its terminal end being the anus, also known as the “Spirit Gate”. The main physiological function of the large intestine is to conduct waste. The large intestine receives the food residue separated by the small intestine, absorbs excess water from it, forming feces, which are then expelled through the anus. The smooth conduction of waste depends not only on the normal function of the large intestine itself but also on the downward movement of the stomach, the dispersing action of the lungs, and the transformation function of the kidneys. Therefore, if the large intestine is diseased, abnormalities in fecal excretion may occur, such as diarrhea or constipation. Additionally, diseases of the large intestine can affect the stomach, lungs, and other organs, leading to dysfunction. (5) Bladder The bladder is located in the lower abdominal cavity, a sac-like organ situated below the kidneys and in front of the large intestine. It connects above to the kidneys via the ureters and below to the urethra, opening at the front. Among the five zang and six fu organs, the bladder is the lowest, serving as the reservoir for excess fluids after metabolism. The main physiological function of the bladder is to store and excrete urine. The fluids ingested by the body are transformed into body fluids through the combined actions of the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and other organs, distributing nourishment throughout the body. After the metabolism of body fluids, the remaining liquid is transported through the pathways of the San Jiao to the kidneys and bladder, transforming into urine, which is stored in the bladder. When the urine in the bladder reaches a certain volume, under the action of the kidneys’ transformation function, the bladder opens, allowing for timely and voluntary excretion. The storage and excretion of urine by the bladder rely entirely on the kidneys’ transformation function. The so-called bladder transformation actually belongs to the kidneys’ vaporization and transformation. Bladder diseases primarily manifest as frequent urination, urgency, and pain during urination; or difficulty urinating, residual urine, or even urinary retention; or enuresis, and in severe cases, urinary incontinence. (6) San Jiao The San Jiao is a unique term in TCM’s organ theory, referring to the upper, middle, and lower Jiao, and is one of the Six Fu organs. Its meridians are closely related to the Pericardium meridian. Throughout history, there have been various interpretations regarding its form and substance, and a complete consensus has yet to be reached. However, there is a general agreement on its physiological functions. In terms of form, it is generally believed that the San Jiao encompasses all internal organs, hence it is also called the “Lonely Palace”. The physiological functions of the San Jiao can be understood from both a holistic and local perspective. From a holistic perspective, the San Jiao governs all qi, overseeing the movement of qi and the circulation of fluids. (1) It governs all qi, overseeing the body’s qi dynamics and transformation. “All qi” refers to all forms of qi in the body, such as the qi of the organs, meridian qi, respiratory qi, and nutritive and defensive qi. The San Jiao’s governance of all qi indicates its close relationship with the physiological activities of the organs, meridians, and tissues. The San Jiao’s ability to govern all qi primarily stems from the original qi, which originates from the lower Jiao, derived from the kidneys and transformed from congenital essence. However, the movement of original qi can only be disseminated and reach the entire body through the pathways of the San Jiao, thus stimulating and promoting the functional activities of various organs and tissues, making the San Jiao play a crucial role in governing all qi. “Qi dynamics” refers to the movement of qi, manifested as the rise and fall of qi, with the San Jiao serving as the channel for the rise and fall of qi. “Transformation” refers to the complex changes of various substances, especially the reception, digestion, and absorption of food and fluids, as well as the conduction and excretion of waste after metabolism. The process of transformation is completed with the participation of multiple organs, and the San Jiao plays an extremely important role in this process. The San Jiao serves as the pathway for the movement of food and the excretion of waste, being the starting and ending point for the circulation of essence and qi throughout the body. Additionally, the San Jiao facilitates the movement of original qi, serving as the power source for transformation, promoting the body’s metabolism. (2) It serves as the pathway for the movement of fluids. The San Jiao has the function of unblocking the pathways of fluids and facilitating their movement, being the channel for the rise and fall of fluids, and is one of the organs involved in regulating fluid metabolism. As stated in the Su Wen, “The San Jiao is the official of drainage, from which the pathways of water emerge.” This indicates that the primary function of the San Jiao is to complete the process of fluid transformation in the body, ensuring the smoothness of the pathways of fluids. If the San Jiao is diseased, qi dynamics may become obstructed, leading to stagnation of both qi and fluids, resulting in symptoms such as edema and ascites. In such cases, methods to unblock the San Jiao are often employed for treatment. (3) It indicates the three parts of the body and their respective physiological functions. In TCM theory, the San Jiao is also a concept for dividing the body into regions: the area above the diaphragm is the upper Jiao, including the heart and lungs; the area below the diaphragm and above the navel is the middle Jiao, mainly including the spleen and stomach; the area below the navel is the lower Jiao, including the liver, kidneys, large and small intestines, bladder, and uterus. Although the liver is anatomically located in the middle Jiao, TCM considers the liver and kidneys to be of the same origin, with a close physiological and pathological relationship, thus both are classified as part of the lower Jiao. Since the upper, middle, and lower Jiao encompass different organs, their physiological functions also differ.