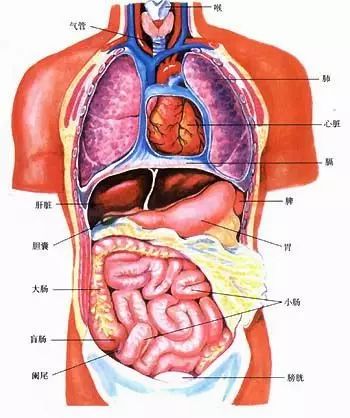

The Six Fu organs refer to the Gallbladder (Dan), Stomach (Wei), Small Intestine (Xiao Chang), Large Intestine (Da Chang), Bladder (Pang Guang), and San Jiao (Triple Burner). Their common physiological function is to “transport and transform substances,” characterized by the principle of “draining without storing” and “solid yet not full.” Food enters through the esophagus into the stomach, where it is processed and then passed to the small intestine. The small intestine separates the clear (essence and fluids) absorbed by the Spleen (Pi) and distributed to the Lungs (Fei) for the body’s needs, while the turbid (waste) is sent to the large intestine, where it is formed into feces for excretion. Waste fluids are transformed by the Kidneys (Shen) into urine, which is stored in the Bladder for excretion. The digestive process involves the seven key passages of the digestive tract, known as the “Seven Passages,” which include the lips as the entrance, teeth as the door, epiglottis as the suction door, stomach as the entrance, the lower stomach as the exit, and the junction of the large and small intestines as the gate, culminating in the lower extremities as the exit (as stated in the “Nanjing, Chapter 44”).

The Six Fu organs refer to the Gallbladder (Dan), Stomach (Wei), Small Intestine (Xiao Chang), Large Intestine (Da Chang), Bladder (Pang Guang), and San Jiao (Triple Burner). Their common physiological function is to “transport and transform substances,” characterized by the principle of “draining without storing” and “solid yet not full.” Food enters through the esophagus into the stomach, where it is processed and then passed to the small intestine. The small intestine separates the clear (essence and fluids) absorbed by the Spleen (Pi) and distributed to the Lungs (Fei) for the body’s needs, while the turbid (waste) is sent to the large intestine, where it is formed into feces for excretion. Waste fluids are transformed by the Kidneys (Shen) into urine, which is stored in the Bladder for excretion. The digestive process involves the seven key passages of the digestive tract, known as the “Seven Passages,” which include the lips as the entrance, teeth as the door, epiglottis as the suction door, stomach as the entrance, the lower stomach as the exit, and the junction of the large and small intestines as the gate, culminating in the lower extremities as the exit (as stated in the “Nanjing, Chapter 44”).

The physiological characteristics of the Six Fu organs involve the reception and transformation of food and fluids, with a tendency towards downward movement. “The Six Fu organs transport and transform substances without storing them, hence they are solid yet not full. This is because when food enters, the stomach is full while the intestines are empty. When food descends, the intestines are full while the stomach is empty” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Five Organs”). Each Fu organ must timely empty its contents to maintain smooth function and coordination, hence the saying, “The Six Fu organs function through passage and follow the principle of descent.” Emphasis is placed on the terms “passage” and “descent”; any excess or deficiency in these functions indicates a pathological state.

1. Gallbladder

The Gallbladder is the foremost of the Six Fu organs and belongs to the extraordinary organs. It is shaped like a pouch, resembling a gourd, and is attached to the liver’s short lobe. The Gallbladder is yang and belongs to wood, while the liver is yin and also belongs to wood. The Gallbladder stores and excretes bile, governs decision-making, and regulates the Qi of the organs.

(1) Anatomy of the Gallbladder

1. Anatomical position: The Gallbladder is connected to the liver, situated between the liver’s short lobes, and is interconnected with the liver through meridians.

2. Structural characteristics: The Gallbladder is a hollow, pouch-like organ that stores bile, a pure, clear, bitter, yellow-green fluid. Thus, it is referred to as the “Middle Essence Organ” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Organs”), “Clear Organ” (as stated in the “Qianjin Yaofang”), and “Middle Clear Organ” (as stated in the “Nanjing, Chapter 35”). The anatomical structure of the Gallbladder is similar to that of other Fu organs, but due to its physiological characteristics of storing essence, it also belongs to the extraordinary organs.

(2) Physiological functions of the Gallbladder

It also interacts with the Five Zang organs in “storing essence and Qi.”

1. Storage and excretion of bile: Bile, also known as “essence fluid” or “clear fluid,” originates from the liver. “The residual Qi of the liver leaks into the Gallbladder, condensing into essence” (as stated in the “Pulse Classic”). Bile is formed and secreted by the liver, then stored and concentrated in the Gallbladder, and through the Gallbladder’s excretory function, it enters the small intestine. Bile “is formed by the Qi transformation of the liver wood, and after eating, it fills the small intestine, pressing the Gallbladder to release its fluid into the small intestine to aid in food digestion and waste elimination. If bile is insufficient, the essence is not differentiated, leading to pale and clean feces without yellow” (as stated in the “Nanjing Zhengyi”). The liver and Gallbladder both belong to the wood element, with one being yin and the other yang, complementing each other. “The Gallbladder is the Fu of the liver, belonging to wood, governing the elevation of clear and the descent of turbid, facilitating the middle earth” (as stated in the “Medical Insights”). Therefore, the Gallbladder also has the function of excretion, but its excretion relies on the liver’s Qi to perform its role.

The bile stored in the Gallbladder is excreted due to the liver’s excretory function, entering the intestines to promote food digestion. If the functions of the liver and Gallbladder are abnormal, the secretion and excretion of bile will be obstructed, affecting the digestive functions of the Spleen and Stomach, leading to symptoms of poor digestion such as loss of appetite, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. If damp-heat accumulates in the liver and Gallbladder, causing the liver to lose its excretory function, bile overflows and saturates the skin, resulting in jaundice, characterized by yellowing of the eyes, skin, and urine. The Qi of the Gallbladder descends; if the Qi is obstructed, it can lead to bitter taste in the mouth, vomiting of yellow-green bitter fluid, etc.

2. Governing decision-making: The Gallbladder governs decision-making, referring to its role in the mental and cognitive processes, enabling judgment and decision-making. The Gallbladder’s role in decision-making is crucial for defending against and eliminating adverse effects from certain mental stimuli (such as extreme fear), maintaining and controlling the normal flow of Qi and blood, and ensuring coordination among the organs. Thus, it is said: “The Gallbladder is the official of central justice, from which decisions are made” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Secret of Linglan”). Mental activities are related to the decision-making function of the Gallbladder, which assists the liver in excretion to regulate emotions. When the liver and Gallbladder work in harmony, emotions are stable. A person with strong Gallbladder Qi is less affected by intense mental stimuli and recovers quickly. Therefore, it is said that strong Qi in the Gallbladder prevents external evils from interfering. Those with weak Gallbladder Qi are more susceptible to adverse effects from mental stimuli, leading to conditions such as timidity, fearfulness, insomnia, and vivid dreams, which can often be treated effectively by addressing the Gallbladder. Thus, it is said: “The Gallbladder is attached to the liver, complementing each other; even if the liver Qi is strong, it cannot function without the Gallbladder. When the liver and Gallbladder work together, courage is achieved” (as stated in the “Classified Classics, Organ Images”).

3. Regulating the Qi of the organs: The Gallbladder works with the liver to assist in the excretion of Qi, facilitating the internal organs and external muscles, maintaining a balanced flow of Qi in all directions, thus ensuring coordination and balance among the organs. When the Gallbladder functions normally, all organs are at ease, hence the saying, “All eleven organs depend on the Gallbladder” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Six Organs”). This means that “all eleven organs rely on the Gallbladder Qi for harmony” (as stated in the “Source of Various Diseases”). The human body is a system of ascending and descending Qi transformation; when the liver Qi is smooth, the Qi of the organs ascends and descends in an orderly manner, maintaining balance between yin and yang, and harmonizing Qi and blood. The Gallbladder is a Fu organ, while the liver is a Zang organ; in the relationship between Zang and Fu, the Zang is primary and the Fu is secondary. Why is it said that “the eleven organs depend on the Gallbladder” rather than “the eleven organs depend on the liver”? Because the liver is yin wood, while the Gallbladder is yang wood, representing the lesser yang. “Yang is the master, and yin is the subordinate” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on Yin and Yang”). Yin is the foundation of yang, and yang governs yin; thus, the Gallbladder, being yang wood, leads the liver, which is yin wood, hence the saying “the eleven organs depend on the Gallbladder.”

In summary, “the eleven organs depend on the Gallbladder” emphasizes that in cognitive activities, the liver governs planning while the Gallbladder governs decision-making. The liver and Gallbladder work together, but this does not imply that the Gallbladder has the role of the “great master of the five Zang and six Fu organs.” The decision-making of the Gallbladder must be guided by the heart to function normally.

(3) Physiological characteristics of the Gallbladder

1. Gallbladder Qi governs ascent: The Gallbladder is the lesser yang among the yang, embodying the wood virtue of the east, belonging to jia wood, and governing the ascending Qi of the lesser yang in spring, hence it is said that Gallbladder Qi governs ascent. The Gallbladder Qi’s ascent reflects its nature of smoothness and is synonymous with the liver’s preference for smoothness and aversion to stagnation. Jiazi is the leader of the five movements and six Qi, corresponding to spring, and represents the lesser yang. When the spring Qi ascends, all things are at peace, which is a natural law. The human body corresponds with heaven and earth; thus, the Gallbladder governs jiazi, and when the Gallbladder Qi ascends, the Qi of the organs flows smoothly. The ascent of Gallbladder Qi, representing the ascent of wood, signifies the smooth excretion of Qi in the organs. When the Gallbladder Qi ascends and flows smoothly, the Qi of the organs ascends and descends normally, maintaining their physiological functions. Therefore, it is said: “The Gallbladder is the lesser yang’s ascending Qi; when the spring Qi ascends, all things transform peacefully, thus the Gallbladder Qi ascends, and the other organs follow. If the Gallbladder Qi does not ascend, then symptoms such as nausea, intestinal obstruction, and other issues arise” (as stated in the “Discussion on the Spleen and Stomach, On the Transformation of Spleen and Stomach Deficiency and Excess”).

2. Preferring tranquility: Tranquility refers to a state of calmness and serenity. The Gallbladder is the organ of clarity, preferring tranquility and disliking disturbances. When tranquil and free from disturbances, the Gallbladder Qi is neither rigid nor soft, embodying the gentle warmth of the lesser yang, thus fulfilling its proper function, and the bile is excreted in a timely manner, allowing for decisive action. If there is evil in the Gallbladder, whether heat, dampness, phlegm, or stagnation, the Gallbladder loses its clarity and tranquility, losing its gentle and harmonious nature, leading to symptoms such as bitter vomiting, restlessness, palpitations, and insomnia, and in severe cases, extreme fear as if being pursued. Clinically, the use of Wending Decoction is aimed at treating restlessness, insomnia, bitter vomiting, and palpitations, intending to restore the Gallbladder’s tranquil and gentle nature to regain its proper function.

2. Stomach

The Stomach is the organ that holds food in the abdominal cavity. It is curved in shape, connecting above to the esophagus and below to the small intestine. It is responsible for receiving and digesting food and is known as the warehouse of the essence of food and the sea of Qi and blood. The Stomach’s function of smooth descent is in harmony with the Spleen, which is its counterpart, as the Stomach is yang and the Spleen is yin.

(1) Anatomy of the Stomach

1. Anatomical position: The Stomach is located below the diaphragm in the upper abdominal cavity, connecting above to the esophagus and below to the small intestine. The cavity of the Stomach is called the Stomach cavity, which is divided into upper, middle, and lower parts: the upper part is the upper cavity, including the entrance; the lower part is the lower cavity, including the exit; the middle cavity is between the upper and lower parts. The entrance connects to the esophagus, and the exit connects to the small intestine, serving as the passage for food entering and exiting the Stomach.

2. Structural characteristics: The Stomach has a curved shape, with a greater and lesser curvature. As stated in the “Lingshu, On the Human Body and the Stomach”: “It is curved, receiving food and fluids, and its shape has a greater and lesser curvature.” The “Lingshu, On the Intestines and Stomach” also states: “The Stomach is curved and bent.”

(2) Physiological functions of the Stomach

1. The Stomach governs the reception of food and fluids: Reception refers to the act of accepting and containing. The Stomach’s function of reception means that it accepts and contains food and fluids. When food enters through the mouth and passes through the esophagus, it is contained and temporarily stored in the Stomach, a process known as reception, hence the Stomach is referred to as the “Great Warehouse” and “Sea of Food and Fluids.” “What humans receive is Qi, and what Qi enters is the Stomach. The Stomach is the sea of food and fluids” (as stated in the “Lingshu, Jade Plate”).

”The Stomach governs reception, thus it is the repository of the five grains” (as stated in the “Classified Classics, Organ Images”). The physiological activities of the body and the generation of Qi, blood, and fluids depend on the nutrition from food, hence the Stomach is also called the sea of Qi and blood. The Stomach’s function of reception is the foundation of its function of digestion, and if the Stomach is diseased, it will affect its reception function, leading to symptoms such as poor appetite, food aversion, and abdominal distension.

The strength of the Stomach’s reception function depends on the abundance of Stomach Qi, which reflects the ability to eat or not eat. If one can eat, the Stomach’s reception function is strong; if one cannot eat, the Stomach’s reception function is weak.

2. The Stomach governs the digestion of food: Digestion refers to the initial breakdown of food in the Stomach, forming chyme. The Stomach’s function of digestion means that it digests food into chyme. “The Middle Jiao is in the Stomach cavity, neither rising nor falling, and governs the digestion of food” (as stated in the “Nanjing, Chapter 31”). The Stomach receives food ingested through the mouth and allows it to stay in the Stomach for a short time for initial digestion, relying on the Stomach’s digestive function to transform food into chyme. After initial digestion, the essence of the food is transported by the Spleen to nourish the entire body, while undigested chyme descends into the small intestine, continuously renewing the digestive process of the Stomach. If the Stomach’s digestive function is weak, symptoms such as Stomach pain and belching of foul-smelling food may occur.

The functions of the Stomach in reception and digestion must be coordinated with the Spleen’s transport function to be completed smoothly. Thus, it is said: “The Spleen is the earth (the earth is yin, while heaven is yang—author’s note). The earth assists the Stomach Qi in digesting food; if the Spleen Qi does not circulate, then the food in the Stomach cannot be digested” (as stated in the “Annotated Treatise on Cold Damage”). The Spleen and Stomach work closely together; “the Stomach governs reception, while the Spleen governs transport; one receives and one transports” (as stated in the “Complete Book of Jingyue, On Food”), allowing food to be transformed into essence, generating Qi, blood, and fluids to nourish the entire body. Therefore, the Spleen and Stomach are referred to as the foundation of postnatal life and the source of Qi and blood generation. The nutrition from food and the digestive function of the Spleen and Stomach are crucial for human life and health. Hence, it is said: “Humans rely on food and fluids for survival; thus, if one is deprived of food and fluids, one dies” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on Human Qi and Weather”).

Traditional Chinese Medicine places great importance on “Stomach Qi,” believing that “humans rely on Stomach Qi for survival.” When Stomach Qi is strong, all five Zang organs thrive; when Stomach Qi is weak, all five Zang organs decline. With Stomach Qi, there is life; without Stomach Qi, there is death. The term Stomach Qi encompasses three meanings: first, it refers to the physiological functions and characteristics of the Stomach. The Stomach is the sea of food and fluids, with the functions of reception and digestion, as well as the characteristics of smooth descent and passage. These functions and characteristics are collectively referred to as Stomach Qi. Since Stomach Qi affects the entire digestive system’s function, it is directly related to the body’s source of nutrition. Therefore, the abundance or deficiency of Stomach Qi is crucial for human life activities and survival, holding significant importance in the life activities of the human body. Thus, in clinical treatment, attention must always be paid to protecting Stomach Qi. Second, it refers to the reflection of the Spleen and Stomach’s functions in pulse manifestations, which exhibit a calm and moderate pulse. Because the Spleen and Stomach digest food and absorb the essence of food and fluids to nourish the entire body, and the essence is transported through the meridians, the abundance or deficiency of Stomach Qi can be reflected in the pulse. Clinically, a pulse indicating Stomach Qi is characterized by a calm and strong pulse, neither fast nor slow. Third, it generally refers to the essence Qi of the human body. “Stomach Qi is the Qi of grains, the Qi of nourishment, the Qi of movement, the Qi of life, the clear Qi, the defensive Qi, and the Yang Qi” (as stated in the “Discussion on the Spleen and Stomach, On Spleen and Stomach Deficiency and the Nine Orifices”).

Stomach Qi can be reflected in appetite, tongue coating, pulse, and complexion. Generally, normal appetite, normal tongue coating, a rosy complexion, and a calm and moderate pulse indicate the presence of Stomach Qi. Clinically, the presence or absence of Stomach Qi is often used as an important basis for judging prognosis; if there is Stomach Qi, there is life; if there is no Stomach Qi, there is death. The so-called protection of Stomach Qi actually means protecting the functions of the Spleen and Stomach. In clinical prescriptions, it is essential to remember “do not harm Stomach Qi”; otherwise, if Stomach Qi fails, all medicines will be ineffective.

(3) Physiological characteristics of the Stomach

1. The Stomach governs smooth descent: The Stomach’s function of smooth descent is in contrast to the Spleen’s function of ascending clarity. The Stomach’s smooth descent means that the Qi of the Stomach should flow smoothly and descend. “When food is digested in the Stomach, its waste is transmitted from the lower mouth of the Stomach to the upper mouth of the small intestine” (as stated in the “Introduction to Medicine, On the Organs”). When food enters the Stomach, after undergoing initial digestion, it must descend into the small intestine, where it is further separated into clear and turbid, with the turbid moving down to the large intestine, eventually forming feces for excretion. This process is accomplished through the smooth descending action of Stomach Qi. Therefore, it is said: “When food enters, the Stomach is full while the intestines are empty; when food descends, the intestines are full while the Stomach is empty” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Five Organs”). “When the Stomach is full, the intestines are empty; when the intestines are full, the Stomach is empty; the more empty and full, the more Qi ascends and descends” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Human Body and the Stomach”). Thus, the Stomach values smooth descent, and the downward movement is in accordance with the principle of smoothness. The theory of organ images in Traditional Chinese Medicine summarizes the physiological functions of the entire digestive system based on the ascending and descending functions of the Spleen and Stomach. The Stomach’s smooth descent also includes the small intestine’s function of transmitting food residues to the large intestine and the large intestine’s function of processing waste. The Spleen should ascend for health, and the Stomach should descend for harmony; when the Spleen ascends and the Stomach descends, they coordinate to complete the digestion and absorption of food.

The Stomach’s smooth descent is a prerequisite for the descent of turbid. Therefore, if the Stomach loses its smooth descent, symptoms such as poor appetite, Stomach distension or pain, constipation, nausea, vomiting, belching, and other signs of Stomach Qi reversal may occur. The Spleen and Stomach reside in the center, serving as the pivot for the body’s Qi ascension and descent. Thus, if Stomach Qi does not descend, it not only directly leads to disharmony in the Middle Jiao but also affects the smooth flow of Qi in the Six Fu organs, potentially leading to various pathological changes.

2. Preferring moisture and disliking dryness: Preferring moisture and disliking dryness refers to the Stomach’s preference for being moistened and its aversion to dryness. The theory of Qi in Traditional Chinese Medicine states that the six Qi (wind, cold, heat, fire, dampness, and dryness) are divided into three yin and three yang, with wind governing the Jueyin, heat governing the Shaoyin, dampness governing the Taiyin, fire governing the Shaoyang, dryness governing the Yangming, and cold governing the Taiyang. The three yin and three yang Qi are further divided into the five movements, with Jueyin wind Qi belonging to wood, Shaoyin heat Qi belonging to fire, Shaoyang fire Qi belonging to fire, Taiyin damp Qi belonging to earth, Yangming dryness Qi belonging to metal, and Taiyang cold Qi belonging to water. “Above Yangming, dryness governs” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Great Theory of the Origin of Heaven”), which refers to the six Qi divided into yin and yang, indicating that dryness governs Yangming, referring to the theory of Qi. The human body corresponds with heaven and earth; thus, Yangming represents the Yangming meridian, which includes the Stomach meridian and the Large Intestine meridian. Both the Stomach and Large Intestine embody dryness Qi. “The human body embodies the dryness Qi of heaven and earth, thus there are the Stomach and Large Intestine; both of them are repositories for the digestion of food and fluids, and since they embody dryness Qi, they must expel water when it enters, preventing it from stagnating in the Stomach” (as stated in the “Annotated Treatise on Cold Damage, Volume 2”). Fire causes dryness, while water causes dampness; Yangming dryness earth must rely on Taiyin damp earth to balance, allowing water and fire to harmonize, maintaining the balance of yin and yang, enabling the Stomach to receive, digest food, and expel turbid. Therefore, it is said: “The Stomach and Large Intestine, in heaven, correspond to the Shen and You constellations, with Shen belonging to the earth and You belonging to metal, and in the four seasons, they correspond to the seventh and eighth months, representing the dry metal’s operational phase. Heaven and earth are merely the transformation of the two Qi of water and fire; when water and fire intersect, they evaporate into moisture, and the interaction of moisture and dryness represents the unchanging Qi of water and fire. If fire does not evaporate water, clouds and rain will not come; if water does not assist fire, dew will not fall” (as stated in the “Annotated Treatise on Cold Damage, Volume 2”). In summary, the Stomach’s preference for moisture and aversion to dryness is primarily reflected in two aspects: first, “the Stomach, being a yang organ, combines with yin essence, and yin essence descends” (as stated in the “Four Sacred Heart Sources”). The descent of Stomach Qi relies on the nourishment of Stomach yin; second, the Stomach’s preference for moisture and aversion to dryness is in harmony with the Spleen’s preference for dryness and aversion to dampness, ensuring the dynamic balance of the Spleen’s ascent and the Stomach’s descent.

3. Small Intestine

The Small Intestine is located in the abdomen, connecting above to the exit of the Stomach and below to the Large Intestine, including the ileum, jejunum, and duodenum. It is responsible for receiving, processing food, and separating the clear from the turbid. It is associated with the Heart and belongs to fire and yang.

(1) Anatomy of the Small Intestine

1. Anatomical position: The Small Intestine is located in the abdomen, with its upper end connecting to the Stomach at the exit and its lower end connecting to the Large Intestine at the gate, serving as the organ for further digestion of food. The Small Intestine is interconnected with the Heart through meridians, thus they complement each other.

2. Structural characteristics: The Small Intestine is a hollow tubular organ that is coiled and folded. “The Small Intestine is attached behind the spine, coiling left and right, with its connection to the ileum (i.e., the Large Intestine) located above the navel, with sixteen coils” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Intestines and Stomach”).

The Small Intestine includes the ileum, jejunum, and duodenum.

(2) Physiological functions of the Small Intestine

1. Governing the reception and processing of food: The Small Intestine’s function of reception and processing refers to its role in receiving and processing food. Reception means accepting and containing food, while processing refers to the transformation and digestion of food. The Small Intestine’s function of reception and processing is reflected in two aspects: first, the Small Intestine receives the food that has been initially digested by the Stomach, serving as a container; second, the food must remain in the Small Intestine for a certain period for further digestion and absorption, transforming food into usable nutrients, with the essence being absorbed and the waste being sent to the Large Intestine, thus performing the function of processing. In pathology, if the Small Intestine’s reception function is impaired, the transport and transformation will cease, leading to stagnation and pain, manifesting as abdominal pain. If the processing function is abnormal, it can lead to digestive and absorption disorders, resulting in symptoms such as abdominal distension, diarrhea, and loose stools.

2. Governing the separation of clear and turbid: Separation refers to the process of distinguishing between the clear and turbid. The Small Intestine separates the essence from the waste during the further digestion of food. The clear refers to the essence, while the turbid refers to the metabolic waste. The process of separating clear and turbid involves two aspects: first, it separates the waste from the food, sending it to the Large Intestine to form feces for excretion; second, it allows the remaining water to be transformed through the Kidney’s Qi transformation, entering the Bladder to form urine, which is then excreted through the urethra. “The Bladder and Kidneys are interrelated, both governing water; water enters the Small Intestine, descends to the Bladder, and is processed for urination” (as stated in the “Source of Various Diseases, On Various Urinary Conditions”). Because the Small Intestine participates in the metabolism of body fluids, it is said that “the Small Intestine governs fluids.” Therefore, Zhang Jingyue stated: “The Small Intestine resides below the Stomach, receiving the food and fluids and separating the clear from the turbid; the fluids are absorbed and sent upward, while the waste descends to the Large Intestine” (as stated in the “Classified Classics, Organ Images”).

The Small Intestine’s functions of reception and processing, as well as the separation of clear and turbid, represent the most critical stage in the entire digestive process. During this process, the chyme is further digested, transforming food into clear (essence containing fluids) and turbid (waste containing residual fluids). The former relies on the Spleen’s transport to be absorbed, while the latter descends into the Large Intestine. The Small Intestine’s digestive and absorption functions are often categorized under the Spleen and Stomach’s functions in the theory of organ images. The Spleen and Stomach’s functions of reception and processing encompass the entirety of modern digestive physiology and part of nutritional physiology. Thus, it is said: “Humans receive food and fluids; the Spleen transforms the essence Qi, which ascends, while the Small Intestine processes the waste, which descends to the Large Intestine” (as stated in the “Medical Origins”). The so-called “the Spleen transforms the essence Qi, which ascends” refers to the Small Intestine’s function of digestion and absorption. Therefore, if the Small Intestine’s digestion and absorption are poor, it falls under the category of Spleen dysfunction, and treatment is often directed at the Spleen and Stomach.

(3) Physiological characteristics of the Small Intestine

The Small Intestine possesses the physiological characteristics of ascending clarity and descending turbid: the Small Intestine processes food and separates the clear from the turbid, transforming food into essence and waste. The essence relies on the Spleen’s ascent to nourish the entire body, while the waste relies on the Small Intestine’s smooth descent to be sent to the Large Intestine. The ascent and descent are interdependent, and the separation of clear and turbid is the Small Intestine’s responsibility. If the ascent and descent are disordered, and the clear and turbid are not distinguished, symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal distension, and diarrhea may occur. The Small Intestine’s ascent and descent of clarity and turbid are specific manifestations of the Spleen’s ascent and the Stomach’s descent functions.

4. Large Intestine

The Large Intestine is located in the abdomen, with its upper end connecting to the Small Intestine at the gate and its lower end connecting to the anus, including the colon and rectum. It is responsible for the transmission and transformation of waste and the absorption of fluids. It belongs to metal and is yang.

(1) Anatomy of the Large Intestine

1. Anatomical position: The Large Intestine is also located in the abdominal cavity, with its upper segment referred to as the ileum (corresponding to the anatomical ileum and upper segment of the colon) and its lower segment referred to as the broad intestine (including the sigmoid colon and rectum). Its upper end connects to the Small Intestine at the gate, while its lower end connects to the anus (also known as the lower extremity or exit). The Large Intestine is interconnected with the Lungs through meridians, thus they complement each other.

2. Structural characteristics: The Large Intestine is a tubular organ, shaped in a coiled manner.

(2) Physiological functions of the Large Intestine

1. Transmission of waste: The Large Intestine’s function of transmission refers to its role in receiving the food residues that descend from the Small Intestine, forming feces for excretion through the anus. The Large Intestine receives the food residues from the Small Intestine, absorbs the remaining water and nutrients, forming feces for excretion, representing the final stage of the entire digestive process, hence it is referred to as the “transmitting organ” or “transmitting official.” Therefore, the primary function of the Large Intestine is to transmit waste and excrete feces. The Large Intestine’s transmission function is closely related to the Stomach’s smooth descent, the Spleen’s transport, the Lungs’ descending function, and the Kidneys’ storage function.

If the Large Intestine is diseased, the transmission will be abnormal, primarily manifesting as changes in the quality and quantity of feces and alterations in bowel movements. If the Large Intestine’s transmission is abnormal, symptoms such as constipation or diarrhea may occur. If damp-heat accumulates in the Large Intestine, leading to Qi stagnation, symptoms such as abdominal pain, urgency, and dysentery with pus and blood may arise.

2. Absorption of fluids: After the Large Intestine receives the food residues and remaining water from the Small Intestine, it reabsorbs some of the fluids, forming feces for excretion. The Large Intestine’s function of reabsorbing fluids is related to the body’s fluid metabolism. Therefore, the Large Intestine’s diseases are often associated with fluids. If the Large Intestine is deficient and cold, it will be unable to absorb fluids, leading to mixed food and water, resulting in symptoms such as intestinal sounds, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. If the Large Intestine is in a state of excess heat, it will consume fluids, leading to dryness and constipation. The majority of the water needed by the body is absorbed in the Small Intestine or Large Intestine, hence it is said that “the Large Intestine governs fluids, while the Small Intestine governs liquids; both the Large and Small Intestines receive the nourishing Qi from the Stomach, enabling them to transport fluids to the upper Jiao, nourishing the skin and filling the pores” (as stated in the “Discussion on the Spleen and Stomach, On the Five Zang and Six Fu Organs Belonging to the Stomach, and the Stomach’s Deficiency Leading to Illness”).

(3) Physiological characteristics of the Large Intestine

The Large Intestine, in the activity of organ functions, is constantly receiving the food residues descending from the Small Intestine and forming feces for excretion, demonstrating a state of accumulation and transmission, being solid yet not full, thus emphasizing smooth descent and function. The Six Fu organs function through passage and follow the principle of descent, with the Large Intestine being the most significant in this regard. Therefore, the smooth descent and downward movement are the important physiological characteristics of the Large Intestine. If the Large Intestine’s smooth descent is abnormal, it often leads to the accumulation of waste and obstruction, hence the saying, “the intestines are prone to fullness.”

5. Bladder

The Bladder, also known as the Clean Fu, Water Palace, Jade Sea, and Urinary Bladder, is located in the lower abdomen, positioned at the lowest part among the organs. It is responsible for storing and excreting urine and is associated with the Kidneys, belonging to the water element and being yang.

(1) Anatomy of the Bladder

1. Anatomical position: The Bladder is located in the lower abdomen, beneath the Kidneys and in front of the Large Intestine. It is positioned at the lowest part among the organs.

2. Structural characteristics: The Bladder is a hollow, pouch-like organ. It has ureters above, connecting to the Kidneys, and a urethra below, opening at the front, known as the urinary orifice.

(2) Physiological functions of the Bladder

1. Storing urine: In the process of fluid metabolism in the human body, water and fluids are distributed throughout the body through the actions of the Lungs, Spleen, and Kidneys, playing a role in moistening the body. After being utilized by the body, the remaining fluids descend to the Kidneys. Through the Kidneys’ Qi transformation, the clear is returned to the body, while the turbid is sent to the Bladder, transforming into urine. Thus, it is said: “The remaining fluids enter the Bladder to become urine; urine is the residue of fluids” (as stated in the “Source of Various Diseases, On Bladder Conditions”), indicating that urine is transformed from fluids. The relationship between urine and fluids is often reciprocal; if fluids are deficient, urine will be scant; conversely, excessive urine can also lead to fluid loss.

2. Excreting urine: When urine is stored in the Bladder and reaches a certain capacity, through the Qi transformation of the Kidneys, the Bladder opens and closes appropriately, allowing urine to be excreted from the urinary orifice.

(3) Physiological characteristics of the Bladder

The Bladder possesses the physiological characteristic of governing opening and closing. The Bladder is the reservoir for the body’s accumulated fluids, thus referred to as the “Fluid Organ” and “Official of the State.” The Bladder relies on its opening and closing functions to maintain a coordinated balance between urine storage and excretion.

The Kidneys are associated with the Bladder, opening at the two yin; “the Bladder is the official of the state, where fluids are stored; when Qi transforms, it can be released. However, if the Kidney Qi is sufficient, it transforms; if the Kidney Qi is insufficient, it does not transform. If the body’s Qi does not transform, water returns to the Large Intestine, leading to diarrhea. If the Qi does not transform, it leads to obstruction in the lower Jiao, resulting in urinary retention. The smooth flow of urine is governed by the Bladder, while the Kidney Qi governs it” (as stated in the “Medical Mirror of the Pen Flower”). The Bladder’s functions of urine storage and excretion rely entirely on the solidifying and transforming functions of the Kidneys. Thus, the Bladder’s Qi transformation is essentially a function of the Kidneys’ Qi transformation.

6. San Jiao (Triple Burner)

San Jiao is a unique term in the theory of organ images. San Jiao refers to the Upper Jiao, Middle Jiao, and Lower Jiao, collectively known as one of the Six Fu organs, and is the largest among the Fu organs, also referred to as the External Fu or Lonely Organ. It governs the ascending and descending of Qi and the circulation of fluids, belonging to fire in the five elements and being yang.

(1) Anatomy of San Jiao

Historically, there has been a debate over whether San Jiao has a physical form or not. Even among those who believe it has a form, there is still no unified view on its essence. However, there is a basic consensus on the physiological functions of San Jiao.

As one of the Six Fu organs, San Jiao is generally considered to be a large organ distributed in the thoracic and abdominal cavities, being the largest and unmatched, hence referred to as the “Lonely Palace.” As Zhang Jingyue stated: “San Jiao is indeed an organ; it exists outside the Zang and Fu, within the body, encompassing all organs, a large organ of one cavity” (as stated in the “Classified Classics, Organ Images”).

Regarding the form of San Jiao, it can be further explored as an academic issue; however, this issue is not the main focus of the theory of organ images itself. The concept of Zang and Fu differs from the anatomical concept of organs; Traditional Chinese Medicine categorizes San Jiao as a separate Fu organ, not merely based on anatomy but more importantly based on the connections of physiological and pathological phenomena to establish a functional system.

In summary, the Upper Jiao is above the diaphragm, including the Heart and Lungs; the Middle Jiao is from the diaphragm to the navel, including the Spleen and Stomach; the Lower Jiao is from the navel to the two yin, including the Liver, Kidneys, Large and Small Intestines, Bladder, and uterus. Among them, the Liver, based on its position, should belong to the Middle Jiao, but due to its close relationship with the Kidneys, both the Liver and Kidneys are categorized under the Lower Jiao. The functions of San Jiao essentially encompass the functions of all the Zang and Fu organs.

(2) Physiological functions of San Jiao

1. Circulating Yuan Qi: Yuan Qi (also known as Original Qi) is the most fundamental Qi in the human body, originating from the Kidneys, transformed from congenital essence, and nourished by acquired essence, serving as the foundation of the yin and yang of the Zang and Fu organs and the original driving force of life activities. Yuan Qi circulates through San Jiao to nourish the Five Zang and Six Fu organs, filling the entire body and stimulating and promoting the functional activities of various organ tissues. Therefore, San Jiao is the channel for the circulation of Yuan Qi. The movement of Qi is the basic characteristic of life. San Jiao’s ability to circulate Yuan Qi is crucial for the Qi transformation activities of the organs. Thus, it is said: “San Jiao is the Qi of the three origins of the human body, overseeing the Five Zang and Six Fu organs, regulating the Qi of the internal and external, upper and lower, left and right. When San Jiao is open, all internal and external, upper and lower are open. Its function of nourishing the body and harmonizing the internal and external, nourishing the left and right, guiding the upper and lower, is unparalleled” (as stated in the “Zhongzangjing”).

2. Regulating the water pathways: “San Jiao is the official of drainage, from which the water pathways emerge” (as stated in the “Suwen, Discussion on the Secret of Linglan”). San Jiao can “regulate the water pathways” (as stated in the “Three Character Classic of Medicine”), playing an important role in controlling the entire process of fluid metabolism in the body. The metabolism of body fluids is a complex physiological process involving multiple organs. Among them, the Upper Jiao’s Lungs serve as the source of water, promoting the distribution and regulation of fluids; the Middle Jiao’s Spleen and Stomach transform and distribute fluids to the Lungs; the Lower Jiao’s Kidneys and Bladder vaporize and transform fluids, allowing them to ascend to the Spleen and Lungs for further metabolism, and then descend to form urine for excretion. San Jiao serves as the pathway for the generation, distribution, and movement of fluids. When San Jiao is functioning well, the meridians are open, and the water pathways are smooth. The role of San Jiao in the fluid metabolism process is referred to as “San Jiao Qi transformation.” The function of San Jiao in circulating fluids essentially summarizes the functions of the Lungs, Spleen, Kidneys, and other organs involved in fluid metabolism.

3. Running food and fluids: “San Jiao is the pathway for food and fluids” (as stated in the “Nanjing, Chapter 31”). San Jiao has the role of running food and fluids, assisting in the distribution of essence and the excretion of waste. The Upper Jiao “develops and distributes the flavors of the five grains, nourishing the skin and filling the muscles” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Qi of Decision”); the Middle Jiao “separates the waste, vaporizes the fluids, and transforms the essence, sending it upward to the Lung meridians” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Circulation of Qi”)); the Lower Jiao “forms waste and sends it down to the Large Intestine, following the Lower Jiao to enter the Bladder” (as stated in the “Lingshu, On the Circulation of Qi”)). The function of San Jiao in running food and fluids, assisting in digestion and absorption, summarizes the functions of the Spleen and Stomach, Liver and Kidneys, Heart and Lungs, and the Large and Small Intestines in completing the digestion, absorption, and excretion of food and fluids.

(3) Physiological characteristics of San Jiao

1. The Upper Jiao is like mist: The Upper Jiao is like mist, referring to its role in distributing defensive Qi and nourishing essence. The Upper Jiao receives the essence from the Middle Jiao’s Spleen and Stomach, distributing it through the Heart and Lungs to nourish the entire body, akin to the nourishing effect of mist. Thus, it is said that “the Upper Jiao is like mist.” Because the Upper Jiao receives essence and distributes it, it is also referred to as “the Upper Jiao governs reception.”

2. The Middle Jiao is like a stew: The Middle Jiao is like a stew, referring to the Spleen and Stomach’s role in transforming food and generating Qi and blood. The Stomach receives and digests food, while the Spleen transforms the essence of food into Qi and blood, distributing it to nourish the entire body. Because the Spleen and Stomach have the physiological function of digesting food and transforming essence, it is likened to “the Middle Jiao is like a stew.” Because the Middle Jiao transforms food into essence, it is referred to as “the Middle Jiao governs transformation.”

3. The Lower Jiao is like a drain: The Lower Jiao is like a drain, referring to the role of the Kidneys, Bladder, and Large and Small Intestines in separating the clear from the turbid and excreting waste. The Lower Jiao transmits the food residues to the Large Intestine, forming feces for excretion, and transforms the remaining fluids into urine through the Qi transformation of the Kidneys and Bladder, which is then excreted. This physiological process emphasizes downward drainage and outward excretion, hence it is said that “the Lower Jiao is like a drain.” Because the Lower Jiao facilitates the excretion of waste, it is also referred to as “the Lower Jiao governs excretion.”

In summary, San Jiao is related to the entire process of receiving, digesting, absorbing, and excreting food and fluids, thus serving as the channel for circulating Yuan Qi and running food and fluids, representing a comprehensive function of the physiological activities of the Zang and Fu organs.