“The theory of the six fu organs being used for communication plays an important guiding role in the treatment of visceral diseases.

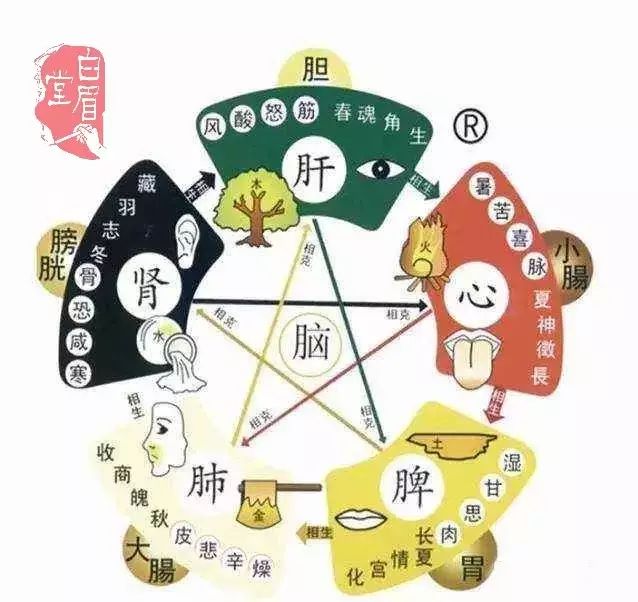

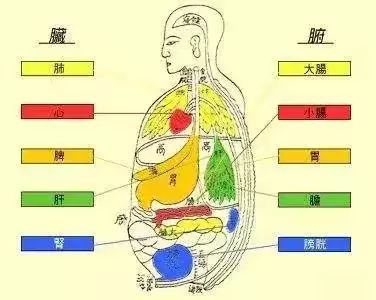

The six fu organs refer to the gallbladder (dan), stomach (wei), small intestine (xiao chang), large intestine (da chang), bladder (pang guang), and san jiao (triple burner). The term ‘fu’ means a storage place. According to the Shuo Wen Jie Zi, ‘fu’ refers to a place where documents are stored. The Yu Pian states: ‘fu’ means origin, gathering, and storage of goods. The fu organs are storage places for grains and goods. Compared to the five zang organs, the six fu organs are more hollow in shape, primarily functioning to receive, digest, and excrete food and waste. Thus, the Ling Shu states, ‘the six fu transmit grains.’ The Suwen states: ‘The six fu transmit and transform substances but do not store, hence they are solid but cannot be full.’ This is because when food and drink enter, the stomach is full while the intestines are empty; when food descends, the intestines are full while the stomach is empty. The Ling Shu also states: ‘The six fu are responsible for transforming food and drink into fluids.’ This indicates that the six fu can transform food and drink, allowing the essence to enter the five zang organs while excreting waste without retention. Therefore, they are described as ‘solid but not full’ and ‘excreting but not storing.’ As stated in the Suwen: ‘The spleen, stomach, large intestine, small intestine, san jiao, and bladder are the foundation of storage and the residence of nourishment, referred to as vessels that can transform waste and allow for entry and exit.’ The Suwen also states: ‘The stomach, large intestine, small intestine, san jiao, and bladder are the five organs born of the heavenly qi; their qi resembles heaven, hence they excrete but do not store, receiving the turbid qi of the five zang organs, known as the vessels of transmission and transformation. They cannot retain for long and are excretory.’

Due to the physiological function of the six fu being to transmit and transform food and excrete waste, they possess the functions of ‘solid but not full’ and ‘storing but not excreting.’ Therefore, under normal circumstances, the six fu must remain unobstructed to facilitate the timely descent of food and the timely excretion of waste. Hence, it is said: ‘The six fu are used for communication’ and ‘the six fu are supplemented by communication.’ As stated in the Clinical Guidelines for Medical Cases: ‘The zang should store, and the fu should communicate; the functions of the zang and fu are different.’ The Classified Evidence and Treatment also states: ‘The six fu transmit and transform but do not store; they are solid but cannot be full, hence communication is used as a supplement.’ If the six fu are obstructed, it leads to food stagnation, waste not being excreted, and qi not flowing smoothly, resulting in symptoms such as abdominal distension and pain, and difficulty in urination and defecation. For example, if food stagnates in the stomach, it leads to stomach distension and pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting; if the gallbladder is obstructed, it leads to rib distension and pain, poor appetite, and reduced food intake; if the large intestine’s transmission is impaired, it results in constipation and abdominal distension and pain; if the bladder is obstructed, it leads to reduced urination, urinary retention, and lower abdominal distension and pain; if the san jiao has qi stagnation, it leads to edema and fullness, and difficulty in urination, etc. Therefore, the functional characteristics of the six fu emphasize smoothness. Although the six fu primarily focus on communication, excessive communication can also lead to various diseases. For instance, if the large intestine’s transmission is excessive, it results in diarrhea and frequent urges to defecate; if the bladder’s communication is excessive, it leads to frequent urination, enuresis, or urinary incontinence. Thus, the six fu should store and excrete in moderation; both excess and deficiency can lead to corresponding diseases. The theory of ‘the six fu are used for communication’ plays an important guiding role in the treatment of visceral diseases. Clinically, for diseases of the six fu, methods to promote communication and expel pathogens are often used. For example, if food stagnates in the stomach, treatment may involve inducing vomiting to expel pathogens or using digestive and stagnation-relieving substances; if the gallbladder is obstructed, treatment may involve methods to promote gallbladder function and communication; for difficulty in urination and defecation, diuretics or laxatives may be used. In cases of excess in the five zang organs, the method of ‘draining the fu corresponding to the zang’ is often employed to drain the corresponding fu to achieve the goal of expelling pathogens and treating diseases. For instance, if there is excess heart fire, herbs that clear the heart and benefit the small intestine are used to expel the heat from the heart through urination; if there is lung heat and obstruction, herbs that promote communication and clear heat from the large intestine are used. Of course, there are also deficiency patterns in the six fu, such as stomach qi deficiency and bladder cold deficiency. Therefore, in clinical treatment of diseases of the six fu, one should not rigidly adhere to the theory of ‘the six fu are used for communication.’ For deficiency patterns of the six fu, it is essential to focus on identifying the cause and treating accordingly, avoiding the pitfalls of confusion between deficiency and excess. Thus, supplementing deficiency and draining excess, supporting the righteous and expelling pathogens, aims to treat the disease at its root and adjust deficiency and excess.

The relationship between the six fu organs is primarily reflected in the digestion, absorption, and excretion of food, demonstrating their interconnection and close cooperation. Food enters the stomach, undergoes initial digestion through the stomach’s rotting and ripening, and then descends to the small intestine. The small intestine receives and transforms substances, further digesting food and separating the clear from the turbid; the clear becomes the essence and fluids that nourish the zang organs, while the turbid becomes food residue, which is then transmitted to the large intestine under the stomach’s descending action. The gallbladder stores and excretes bile to assist the small intestine in digestion. The large intestine transmits changes, absorbs excess water from food residue, dries the waste, and forms feces, which are then expelled through the anus. The bladder stores urine, which is expelled in a timely manner through the action of qi transformation. The original qi circulates through the san jiao, promoting the normal functioning of transmission and transformation. Since the six fu transmit and transform food and drink, they require continuous reception, digestion, transmission, and excretion, with a cycle of deficiency and excess, favoring communication and disfavoring stagnation. Thus, Ye Tian Shi stated in the Clinical Guidelines for Medical Cases: ‘The six fu should all be open and unobstructed.’ Later physicians also stated, ‘The six fu are used for communication, and diseases of the fu are supplemented by communication.’

In pathological conditions, diseases of the six fu are often characterized by obstruction and blockage, frequently affecting each other and being mutually causal. For example, if there is excess heat in the stomach, it can consume fluids, leading to impaired transmission in the large intestine and resulting in constipation; conversely, if the large intestine is dry and constipated, it can affect the stomach’s ability to descend, causing stomach qi to rebel, leading to nausea and vomiting. If the liver fails to regulate, abnormal secretion and excretion of bile can affect the stomach, causing rib pain, jaundice, nausea, and vomiting; it can also affect the small intestine, leading to abdominal distension and diarrhea; or manifest as simultaneous diseases of the gallbladder, stomach, and small intestine. Excess heat in the small intestine can affect the bladder’s storage and urination functions, leading to pathological changes such as short and red urination. Although the six fu are used for communication, their diseases can also vary in excess and deficiency, blockage and smoothness, and upward and downward movement.

The six fu include: gallbladder, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, bladder, and san jiao. Their common physiological characteristic is to receive and transform food and drink. In ancient times, ‘fu’ was written as ‘府,’ which is hollow and serves as a storage place for items, allowing for entry and exit. The physiological function of the six fu primarily involves ‘transmission and transformation,’ indicating that the main function of the six fu is to receive, rot, digest, and transform food, existing in a continuous cycle of deficiency and excess. The six fu do not store essence and qi. From the entry of food into the body to its excretion, it passes through seven important gates, referred to as the ‘Seven Gates’ in the Nanjing: the lips, teeth, epiglottis, cardia, pylorus, ileocecal junction, and anus. The lips serve as the ‘flying gate,’ meaning they can open and close freely; the teeth serve as the ‘door gate,’ meaning they guard the upper end of the digestive tract and can chew food; the epiglottis serves as the ‘suction gate,’ referring to the junction of the esophagus and trachea, which is the portal for air entering and exiting the body; the cardia is the upper opening of the stomach, where food enters the stomach; the pylorus is the lower opening of the stomach, connecting to the small intestine; the ileocecal junction is where the small intestine meets the large intestine, preventing the essence from flowing into the large intestine; the anus, also known as the ‘exit gate,’ is the final end of the digestive tract, allowing for the excretion of feces. Therefore, any pathological changes in any part of the Seven Gates will affect the reception, digestion, absorption, and excretion of food.

(1) Gallbladder: The gallbladder is attached to the liver and is a hollow sac-like organ. Its main physiological function is to store and excrete bile. Bile is produced in the liver and secreted by it. After bile is generated, it flows into the gallbladder for storage. Bile, also known as essence juice, is referred to as the ‘house of essence.’ Bile is yellow-green and extremely bitter, playing an important role in digestion. After eating, through the liver’s regulating action, bile is released into the intestines to assist the spleen and stomach in maintaining normal digestion. Due to the close relationship between the liver and gallbladder, if the liver functions normally, bile production and excretion will be smooth, allowing for normal digestion. If there is a disease in the liver, it can affect bile production and excretion, leading to digestive dysfunction. For example, if gallbladder qi rebels, bile can rise, causing a bitter taste in the mouth; if bile excretion is obstructed and cannot smoothly enter the intestines, symptoms such as loss of appetite, abdominal distension, and loose stools may occur; diseases of the gallbladder and stomach can also lead to nausea and vomiting; if the liver and gallbladder fail to regulate, bile may overflow into the skin, resulting in jaundice; if bile stagnates and transforms into heat, damp-heat accumulation can further cook the bile, leading to the formation of stones. Although the gallbladder is one of the six fu, it primarily stores essence juice and is a clean house, not directly receiving food waste, which differentiates it from other fu, thus it is classified as a special fu.

(2) Stomach: The stomach is located below the diaphragm, with its upper opening known as the cardia, connecting to the esophagus, and its lower opening known as the pylorus, connecting to the small intestine. The stomach, also referred to as the ‘stomach cavity,’ is divided into three parts: upper, middle, and lower. The upper part is the ‘upper cavity,’ including the cardia; the lower part is the ‘lower cavity,’ including the pylorus; the middle part is the ‘middle cavity,’ which is the body of the stomach. The main physiological functions of the stomach can be summarized in two aspects: (1) It is responsible for receiving and rotting food and drink. Food enters through the mouth, passes through the esophagus, and enters the stomach, where it is received; thus, the stomach is also called the ‘sea of food and drink,’ as the physiological activities of the body and the transformation of qi, blood, and fluids depend on the nourishment from food, hence the stomach is also referred to as the ‘sea of qi and blood from food and drink.’ Therefore, if there is a disease in the stomach, it can easily affect its function of receiving food, leading to symptoms such as loss of appetite and aversion to food. ‘Rotting’ implies initial processing and digestion. Food in the stomach undergoes kneading and digestive actions, transforming into chyme and descending into the small intestine, laying the foundation for further digestion. The reception and rotting functions of the stomach are integrated with the transportation function of the spleen, referred to as ‘stomach qi.’ ‘Human beings rely on stomach qi for life; with stomach qi, there is life; without stomach qi, there is death.’ (2) It is responsible for descending, allowing food to enter the stomach, undergo rotting, and then enter the small intestine for further digestion and absorption, with the turbid portion descending to the large intestine to form feces for excretion. Thus, the stomach governs descent, and descent is harmonious. If the stomach does not harmonize and descend, food can stagnate in the stomach, leading to symptoms such as stomach distension and pain, and loss of appetite. If stomach qi rebels, symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, belching, and hiccups may occur. Additionally, if stomach qi does not descend, it can also affect the spleen’s function of ascending the clear.

(3) Small Intestine: The small intestine is located in the abdomen, connecting above to the pylorus and the stomach, and below to the ileocecal junction and the large intestine. The physiological functions of the small intestine can be summarized in two aspects: (1) It receives and holds food. ‘Receiving’ means to hold substances, indicating acceptance. The small intestine receives food that has been initially digested by the stomach, thus it serves as a vessel for the contents of the stomach. Food remains in the small intestine for a longer time to facilitate further digestion, allowing the essence of food to nourish the entire body. If the small intestine’s function of receiving food is impaired, it can lead to digestive and absorption disorders, manifesting as abdominal distension, diarrhea, and loose stools. ‘Transforming’ means changing, digesting, and generating; the small intestine’s transforming function is to further digest and absorb the food that has been initially digested by the stomach. (2) It separates the clear from the turbid. The ‘clear’ refers to various essences, while the ‘turbid’ refers to the residual portion of food after digestion. The small intestine’s function of separating the clear from the turbid specifically includes three aspects: first, it separates the digested food into two parts, namely the essence and the waste; second, it absorbs the essence of food and transports the residue to the large intestine; third, while absorbing the essence of food, the small intestine also absorbs a large amount of water and sends the useless water to the bladder to form urine. Thus, the physiological function of the small intestine is crucial in the digestion of food. When the small intestine functions normally, the clear and turbid each follow their path, the essence is distributed throughout the body, the waste is sent to the large intestine, and the useless water is sent to the bladder. If there is a disease in the small intestine, it can not only cause digestive dysfunction, leading to symptoms such as abdominal distension and pain, but also affect the excretion of urine and feces, for example, leading to reduced urination and loose stools. In such cases, methods to promote separation are often used, known as ‘promoting urination to solidify stools.’

(4) Large Intestine: The large intestine is also located in the abdomen, connecting above to the small intestine at the ileocecal junction, and its end is the anus, also known as the ‘exit gate.’ The main physiological function of the large intestine is to conduct waste. The large intestine receives the food residue that has been separated into clear and turbid by the small intestine, absorbs excess water from the residue, dries the waste, and forms feces, which are then expelled through the anus. The smooth conduction of waste depends on the normal function of the large intestine itself, as well as the descending action of the stomach, the descending function of lung qi, and the transformation function of the kidneys. Therefore, if there is a disease in the large intestine, it primarily manifests as abnormalities in fecal excretion, such as diarrhea or constipation. Additionally, diseases of the large intestine can also affect the stomach, lungs, and other organs, leading to dysfunction.

(5) Bladder: The bladder is located in the lower abdominal cavity, a sac-like organ situated below the kidneys and in front of the large intestine. It connects above to the kidneys via the ureters and below to the urethra, opening at the front. Among the five zang and six fu organs, the bladder is the lowest, serving as a reservoir for excess water after fluid metabolism. The main physiological function of the bladder is to store and excrete urine. The water consumed by the body is transformed into fluids through the combined actions of the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and other organs, distributing throughout the body to nourish and moisten. After the metabolism of fluids, the remaining liquid is sent down through the pathways of the san jiao to the kidneys and bladder, transforming into urine, which is stored in the bladder. When the urine in the bladder reaches a certain volume, under the action of qi transformation from the kidneys, the bladder opens, allowing for timely and voluntary excretion. The storage and excretion of urine by the bladder rely entirely on the transformation function of the kidneys. The so-called bladder transformation actually belongs to the vaporization of the kidneys. The pathological changes of the bladder primarily manifest as frequent urination, urgency, and pain; or difficulty in urination, residual urine, and even urinary retention; or enuresis, and in severe cases, urinary incontinence.

(6) San Jiao: San jiao is a unique term in the theory of TCM organ representation, referring to the upper jiao, middle jiao, and lower jiao, and is one of the six fu. Its meridian is related to the pericardium. Throughout history, there have been various interpretations regarding its morphology and substance, and a complete consensus has yet to be reached. However, there is a general agreement on its physiological functions. In terms of morphology, it is generally believed that the san jiao encompasses all internal organs, hence it is also called the ‘lonely fu.’ The physiological functions of the san jiao can be understood from both a holistic and local perspective. From a holistic perspective, the san jiao governs all qi and is responsible for the qi transformation and movement of fluids in the body. (1) Governing all qi, overseeing the qi mechanism and qi transformation: ‘All qi’ refers to all forms of qi in the body, such as the qi of the zang and fu, the qi of the meridians, the qi of respiration, and the qi of nourishment and defense. The san jiao’s governance of all qi indicates that it has a close relationship with the physiological activities of the zang, fu, meridians, and tissues. The reason the san jiao can govern all qi is primarily due to the original qi. The original qi originates from the lower jiao, derived from the kidneys, transformed from congenital essence. However, the movement of original qi can only be disseminated and reach the entire body through the pathways of the san jiao, thus stimulating and promoting the functional activities of various zang and fu organs, which is why the san jiao plays a role in governing all qi. ‘Qi mechanism’ refers to the movement of qi, manifested as the rise and fall of qi. The san jiao serves as a channel for the rise and fall of qi. ‘Qi transformation’ refers to the complex changes of various substances, especially the reception, digestion, absorption of food and drink, as well as the transmission and excretion of waste after the metabolism of nutrients. The qi transformation process is completed with the participation of multiple zang and fu organs, and the san jiao plays a crucial role in this process. The san jiao serves as the pathway for the transformation of food and drink and the excretion of waste, being the starting point for the movement of essence and qi throughout the body. Additionally, the san jiao facilitates the movement of original qi, serving as the source of power for qi transformation, promoting the body’s metabolism. (2) It serves as a channel for the movement of fluids: The san jiao has the function of unblocking the pathways of fluids and facilitating their movement, serving as a pathway for the rise and fall of fluids, and is one of the organs involved in regulating fluid metabolism. As stated in the Suwen: ‘The san jiao is the official of drainage, from which the pathways of water emerge.’ This indicates that the primary function of the san jiao is to complete the process of fluid transformation in the body, ensuring the smoothness of the water pathways. If there is a disease in the san jiao, qi blockage can lead to stagnation of both qi and water, resulting in symptoms such as edema and ascites. In such cases, methods to promote the san jiao are often used for treatment. (3) It indicates the three parts of the body and their respective physiological functions.

In TCM theory, the san jiao is also a concept for dividing body parts: the area above the diaphragm is the upper jiao, including the heart and lungs; the area below the diaphragm and above the navel is the middle jiao, primarily including the spleen and stomach; the area below the navel is the lower jiao, including the liver, kidneys, large and small intestines, bladder, and uterus. Although the liver should be classified as part of the middle jiao based on its location, TCM considers the liver and kidneys to be of the same origin, with a close physiological and pathological relationship, thus both are classified as part of the lower jiao. Since the upper, middle, and lower jiao encompass different organs, their physiological functions also differ. (1) Upper jiao is like mist: ‘Mist’ refers to a diffused and vaporous state of the essence of food and drink. The upper jiao, like mist, refers to the function of the upper jiao in dispersing and nourishing the skin, hair, and all internal organs with qi. Thus, the function of the upper jiao is actually reflected in the qi transformation and distribution of the heart and lungs, relating to the distribution of nutrients such as qi, blood, and fluids. Therefore, variations in the function of the upper jiao primarily reflect abnormalities in heart and lung function, with treatment focusing on regulating the heart and lungs. (2) Middle jiao is like fermentation: ‘Fermentation’ here refers to the image of food undergoing rotting and fermentation. The middle jiao, like fermentation, refers to the function of the spleen and stomach in transforming the essence of food and drink. The function of the middle jiao primarily refers to the physiological functions of the spleen and stomach, such as the reception and digestion of food, absorption of nutrients, vaporization of body fluids, and transformation of essence into blood. In fact, the middle jiao serves as the pivot for the rise and fall of qi and the source of the generation of qi and blood. Thus, the function of the middle jiao is described as ‘like fermentation.’ Variations in the function of the middle jiao primarily reflect abnormalities in spleen and stomach function, with treatment focusing on regulating the spleen and stomach. (3) Lower jiao is like a drainage channel: ‘Drainage channel’ refers to the pathway for excreting water. The lower jiao governs the separation of clear and turbid, and the excretion of urine and feces, a process that actually includes the functions of the kidneys, small intestine, large intestine, and bladder. Therefore, variations in the function of the lower jiao primarily reflect abnormalities in kidney and bladder function, with treatment focusing on regulating the kidneys and bladder.