Pulse Diagnosis

Pulse diagnosis is divided into two parts: pulse diagnosis and pressure diagnosis. Both methods involve the use of the hands to touch, feel, and press on the patient’s body surface to obtain important diagnostic information. Pulse diagnosis refers to the examination of the pulse; pressure diagnosis involves touching and pressing on the skin, hands, feet, chest, abdomen, and other areas. In ancient times, pulse diagnosis originally referred to pulse examination, but pressure diagnosis has existed for a long time and has developed over time. Therefore, pulse diagnosis should include both pulse examination and pressure examination.

I. Pulse Diagnosis

Pulse diagnosis has ancient methods such as the comprehensive examination method, three-part examination method, and cun-kou examination method. In later generations, the cun-kou examination method became the main focus, and based on the position, number, shape, and quality of the pulse, it is classified into twenty-eight types of pulse patterns to understand internal bodily changes. Diagnosing the pulse relies entirely on the physician’s sensitive tactile perception, so it is essential to accurately distinguish the locations and pulse patterns. In addition to being familiar with pulse diagnosis theory, one must also practice extensively to master this diagnostic method.

1. The Principles of Pulse Formation and the Clinical Significance of Pulse Diagnosis

(1) The Principles of Pulse Formation: The heart governs the blood vessels, and the heart’s contractions push blood into the vessels, forming the pulse. The heart’s contractions and the blood’s movement in the vessels are driven by the zong qi (ancestral qi). As stated in the Suwen: Theory of Qi in the Normal Person: “The great network of the stomach is called xuli,… it emerges from below the left nipple, and its movement responds to the hand (the original text had ‘clothing’, modified according to the Jia Yi Jing), the pulse is the zong qi.” This indicates that zong qi has the function of promoting the heart’s contractions. The Ling Shu: Chapter on Evil Guests further states: “Zong qi accumulates in the chest, emerges from the throat, and penetrates the heart pulse…” This not only indicates the location of zong qi but also points out its important role in promoting blood circulation. Blood circulates through the vessels, flowing throughout the body continuously. In addition to the heart’s leading role, there must also be coordination among various organs: the lungs govern the hundred pulses, which circulate throughout the body, converging in the lungs, and the lungs govern qi. Through the distribution of lung qi, blood can spread throughout the body; the spleen and stomach are the sources of qi and blood production, with the spleen governing blood, and the circulation of blood relies on the spleen’s regulation; the liver stores blood and regulates circulation; the kidneys store essence, which transforms into qi, serving as the fundamental source of yang qi in the body, and the driving force for the functional activities of all organs and tissues. Moreover, essence can transform into blood, making it one of the material bases for blood production. Therefore, the formation of pulse patterns is closely related to the qi and blood of the organs.

(2) The Clinical Significance of Pulse Diagnosis: Since the formation of pulse patterns is closely related to the qi and blood of the organs, when the qi and blood of the organs undergo pathological changes, the circulation of blood is affected, leading to changes in pulse patterns. Thus, by examining the pulse patterns, one can determine the location of the disease and infer its prognosis.

① Determining the location, nature, and the balance of pathogenic and healthy qi of the disease. Although the manifestations of diseases are extremely complex, in terms of the depth of the disease location, it is either superficial or deep. The floating or sinking nature of the pulse often reflects the depth of the disease location: a floating pulse usually indicates a superficial condition, while a sinking pulse indicates a deeper condition. The nature of the disease can be divided into cold and heat patterns, and the rate of the pulse can reflect the nature of the disease. For example, a slow pulse often indicates a cold pattern, while a rapid pulse often indicates a heat pattern. In the process of disease development, the struggle between pathogenic and healthy qi leads to pathological changes of deficiency and excess, and the strength or weakness of the pulse can reflect the deficiency or excess of the disease. Xu Ling Tai said: “The key to deficiency and excess cannot escape the pulse.” A weak and powerless pulse indicates a deficiency of healthy qi; a strong pulse indicates an excess of pathogenic qi.

② Inferring the progression and prognosis of the disease. Pulse diagnosis has certain clinical significance in inferring the progression and prognosis of the disease. For example, if a long-term illness shows a gradual softening of the pulse, it indicates that the stomach qi is gradually recovering, and the disease is retreating towards recovery; if a long-term illness is characterized by qi deficiency, weakness, or blood loss, and a flooding pulse appears, it often indicates a dangerous condition of excess pathogenic qi and deficiency of healthy qi. In cases of externally contracted febrile diseases, if the heat gradually subsides and the pulse shows a softening, it is a sign of recovery; if the pulse is rapid and agitated, it indicates disease progression. Similarly, in cases of sweating from battle, if the sweat is profuse and the pulse is calm, with the body feeling cool, it indicates that the disease is retreating towards recovery; if the pulse is rapid and agitated, it indicates disease progression. As stated in the Jing Yue Quan Shu: Chapter on Pulse Spirit: “To observe the progression and prognosis of the disease, one should focus on the stomach qi. The method of observation is as follows: if today the pulse is still soft, but tomorrow it becomes rapid, it indicates that the pathogenic qi is advancing; if the pulse is rapid today and slightly soft tomorrow, it indicates that the stomach qi is gradually returning, and as the stomach qi returns, the disease gradually lightens. If the pulse is initially rapid and then softens, it indicates the arrival of stomach qi; if it is initially soft and then becomes rapid, it indicates the departure of stomach qi. This is the method to observe the progression of pathogenic and healthy qi.” It must be pointed out that the relationship between the pulse and the disease is very complex. Generally speaking, the pulse symptoms correspond to the disease symptoms, as Zhou Xuehai said: “If there is a disease, there is a corresponding pulse.” However, there are also special cases where the pulse symptoms do not correspond to the disease symptoms, hence the terms “following the pulse over the symptoms” or “following the symptoms over the pulse”. In clinical practice, one should consider all four diagnostic methods to obtain an accurate diagnosis.

2. The Locations of Pulse Diagnosis

Regarding the locations of pulse diagnosis, there are comprehensive examination methods, three-part examination methods, and cun-kou examination methods.

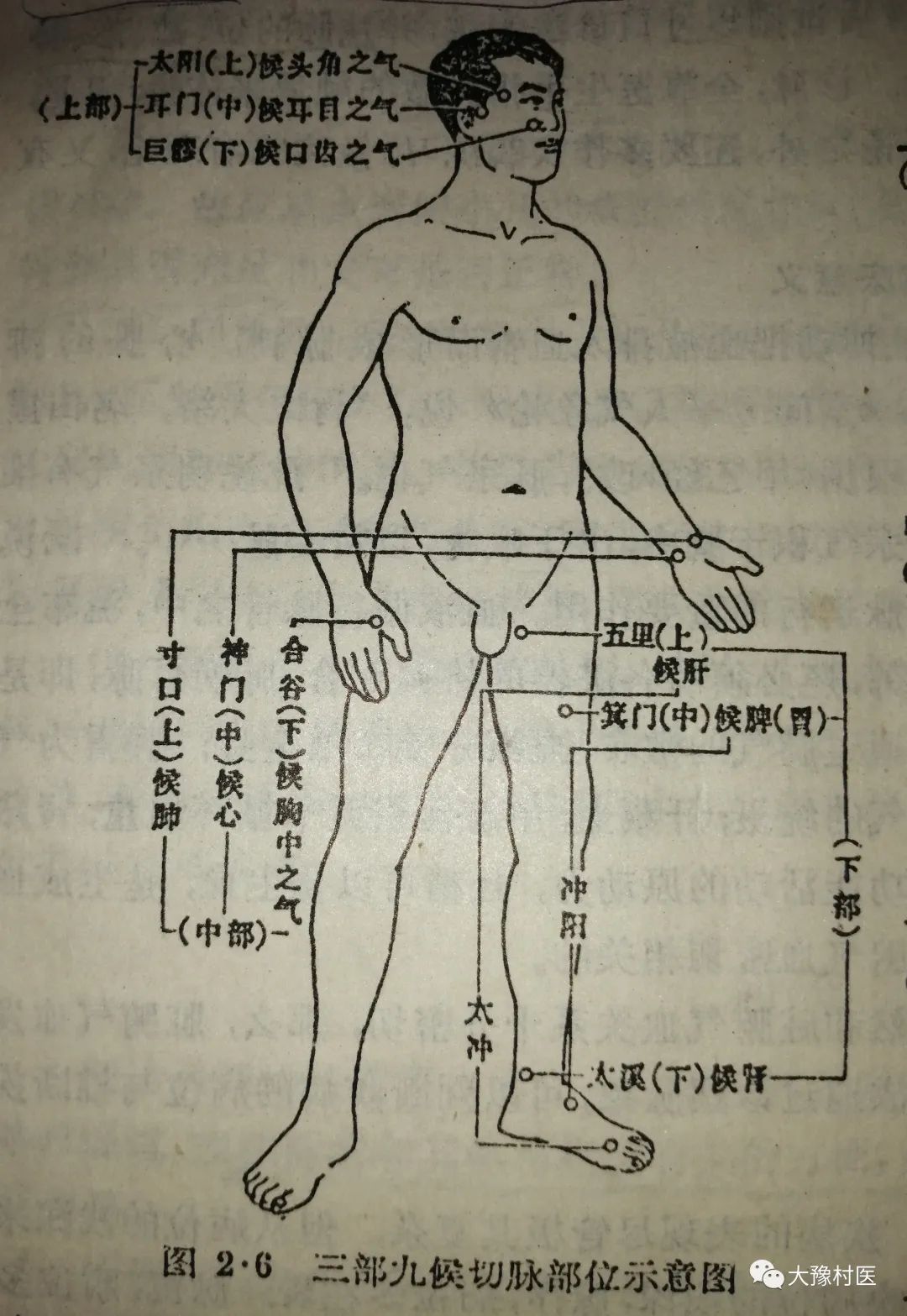

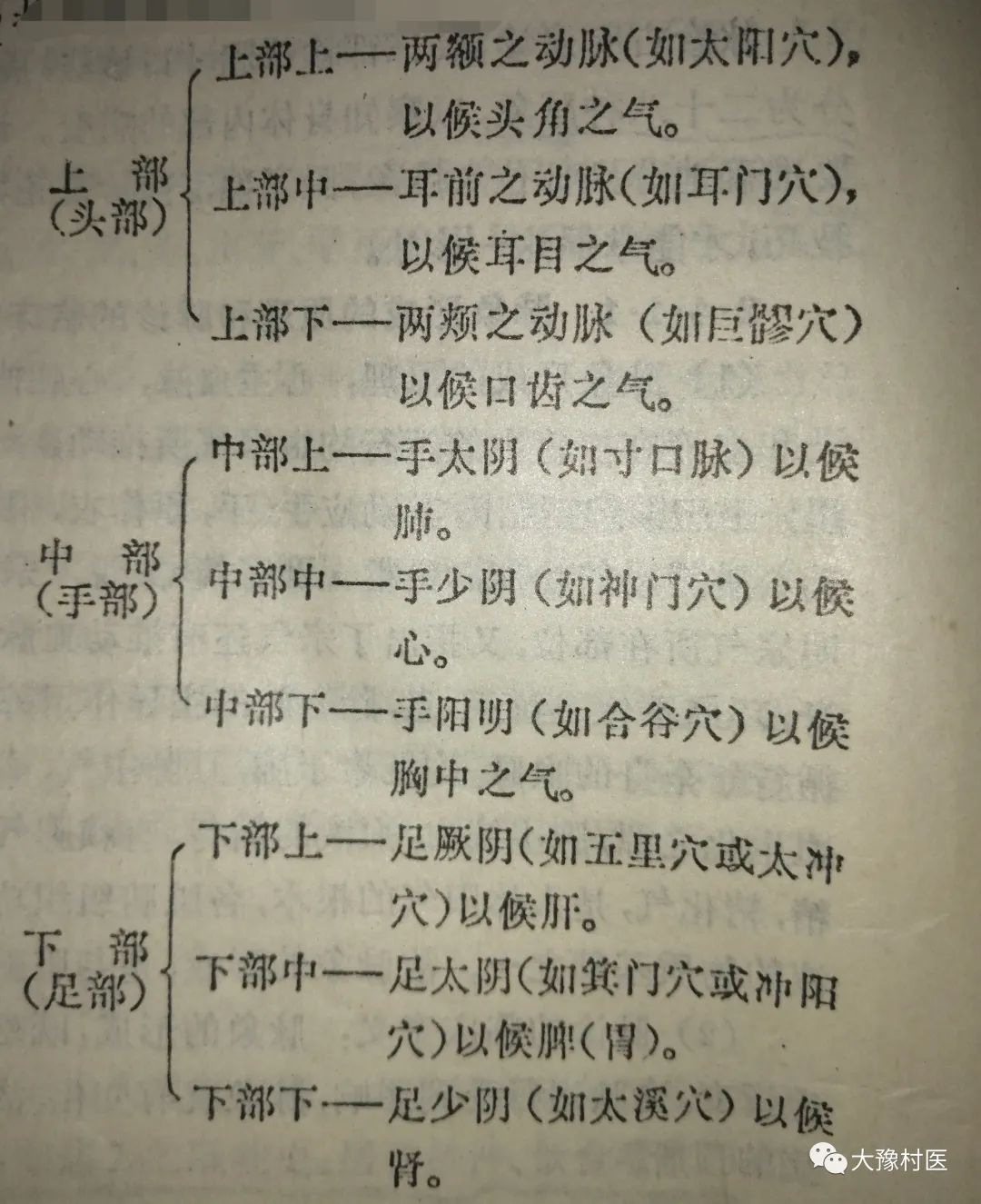

(1) Comprehensive Examination Method:(also known as the Suwen three-part nine-pulse method). The locations for pulse examination include the head, hands, and feet, each of which is further divided into three categories: heaven, earth, and human, making a total of nine categories, hence the name three-part nine-pulse method. The specific locations are as follows (see diagram)

(2) Three-Part Examination Method: Originating from Zhang Jing’s Shang Han Lun during the Han Dynasty. It includes the Renying, Cun-kou, and Dieyang pulses. Among these, the cun-kou pulse examines the twelve meridians, while the Renying and Fuyang pulses assess the stomach qi. It is also possible to include the foot shaoyin (Taixi point) to assess the kidney qi.These two pulse examination locations have been less commonly used in later generations (only in critical conditions and when there is no pulse in both hands, the Renying, Dieyang, and Taixi pulses are examined to determine the presence or absence of stomach and kidney qi). Since the Jin Dynasty, the commonly used pulse examination location has been the cun-kou.

(3) Cun-Kou Examination Method: First mentioned in the Nei Jing, detailed in the Nanjing, and popularized in Wang Shuhe’s Pulse Classic during the Jin Dynasty. The cun-kou, also known as the qi-kou or pulse-kou, is located at the radial artery on the back of the wrist.

The theoretical basis for exclusively using the cun-kou for pulse diagnosis: Why can the cun-kou pulse reflect the changes in the five zang and six fu organs? The Suwen: Discussion on the Five Zang states: “Why is the qi-kou uniquely responsible for the five zang? It is said that the stomach is the sea of water and grains, the great source of the six fu. The five flavors enter and are stored in the stomach to nourish the qi of the five zang; the qi-kou is also taiyin. Therefore, the qi and flavors of the five zang and six fu all emerge from the stomach and manifest at the qi-kou.” The Nanjing: First Difficulty further states: “All twelve meridians have arteries, but only the cun-kou is used to determine the life and death of the five zang and six fu. Why is that? Because the cun-kou is the great meeting of the pulse, the artery of the hand taiyin.” The discussions in the Suwen and Nanjing illustrate the interrelatedness and mutual influence of the five zang organs, which are reflected in the pulse. The source of the pulse begins in the stomach, is transmitted through the spleen, and nourishes the five zang and six fu organs. After passing through the five zang and six fu organs, it returns to the lungs through the hundred pulses, and is influenced by the pathological changes of the organs, which can be reflected in the cun-kou pulse.

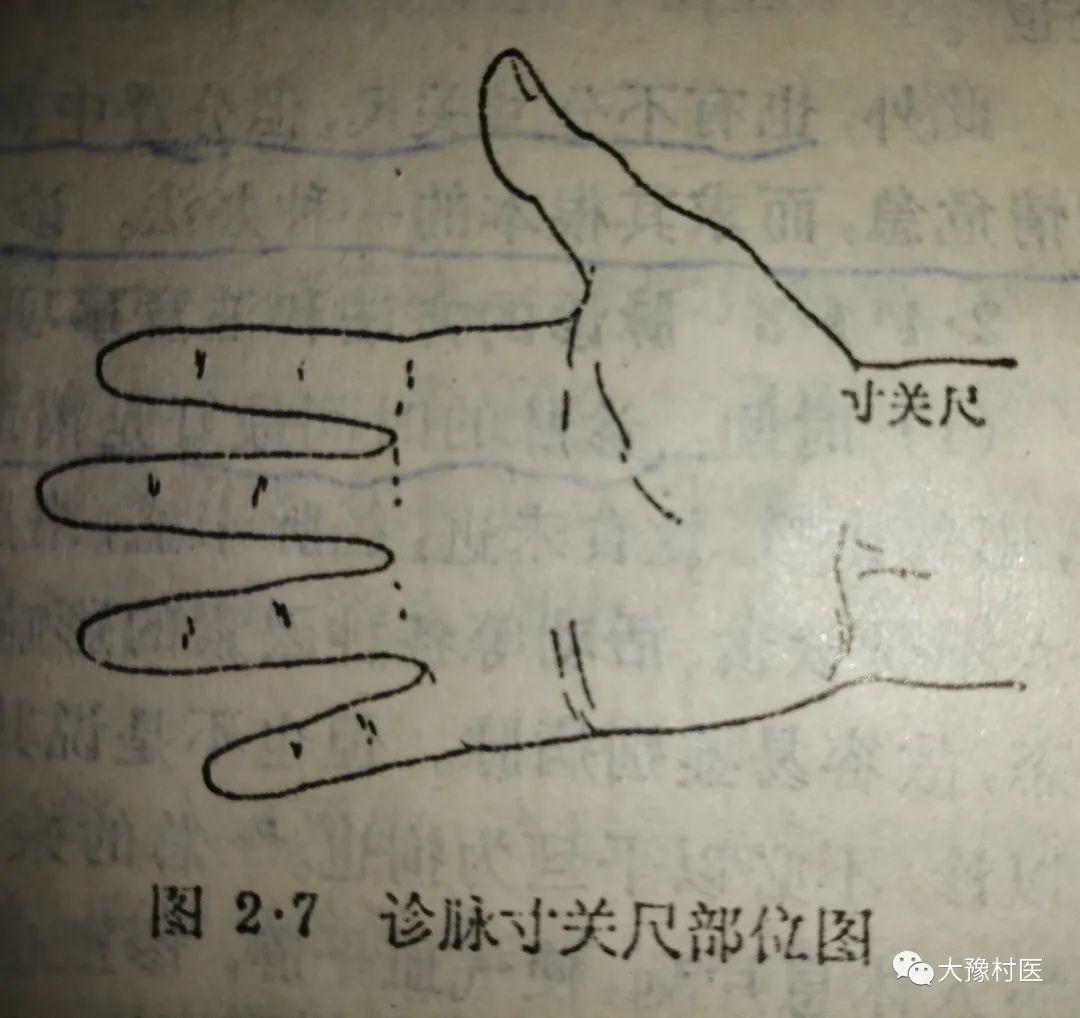

The cun-kou is divided into three parts: cun, guan, and chi. The Pulse Classic states: “From the fish mound to the high bone. Move back one cun, this is called cun-kou; from cun to chi, it is called chi-ze, hence the name cun and chi. The area behind the cun is called guan, and the area behind the chi is called chi.” The high bone serves as the reference point (the radial styloid process), and the slightly inward area is the guan, the area before the wrist is the cun, and the area behind the elbow is the chi. Each hand has three parts: cun, guan, and chi, totaling six pulse locations (see diagram).

The cun, guan, and chi can be further divided into floating, middle, and sinking categories, which is the three-part nine-pulse method of the cun-kou examination. The Nanjing: Eighteenth Difficulty states: “The three parts are cun, guan, and chi; the nine categories are floating, middle, and sinking.” This is similar in name to the three-part nine-pulse method but different in essence.

The division of the cun, guan, and chi corresponds to the organs; it first appears in the Nei Jing, and according to the Suwen: Essentials of Pulse, it is described as follows:

Left cun: externally assesses the heart, internally assesses the zhong (sternum). Right cun: externally assesses the lungs, internally assesses the chest.

Left guan: externally assesses the liver, internally assesses the diaphragm. Right guan: externally assesses the spleen, internally assesses the stomach.

Left chi: externally assesses the kidneys, internally assesses the abdomen. Right chi: externally assesses the kidneys, internally assesses the abdomen.

Later generations have generally based the division of the cun, guan, and chi on the Nei Jing with slight modifications. For example, the Nanjing pairs the small intestine and large intestine with the heart and lungs, using the right kidney as the gate of life; the Pulse Classic pairs the sanjiao with the right chi; Zhang Jingyue pairs the bladder and large intestine with the left chi, using the sanjiao as the gate of life, and the small intestine with the right chi; the Yi Zong Jin Jian pairs the left cun with the heart and zhong, the right cun with the lungs and chest, the left guan with the liver, gallbladder, and brain, and the right guan with the spleen and stomach. Both chi assess the kidneys, with the left chi paired with the small intestine and bladder, and the right chi paired with the large intestine, also assessing the three parts of the sanjiao.

The aforementioned theories have some differences regarding the small and large intestines and the sanjiao, but the main viewpoints regarding the division of the five zang organs are consistent. Currently, the following is commonly accepted regarding the division of the cun, guan, and chi:

Left cun can assess: heart and zhong; right cun can assess: lungs and chest.

Left guan can assess: liver, gallbladder, and diaphragm; right guan can assess: spleen and stomach.

Left chi can assess: kidneys and lower abdomen; right chi can assess: kidneys and lower abdomen.

This method of allocation is based on the principle of “upper corresponds to upper, lower corresponds to lower” as stated in the Nei Jing, reflecting the principle that the upper (cun pulse) assesses the upper body and the lower (chi pulse) assesses the lower body. However, it must be pointed out that the division of the cun, guan, and chi corresponds to the qi of the five zang and six fu organs, rather than the location of the pulse of the organs, as Li Shizhen said: “The pulses of both hands in all six parts are all from the lung meridian; this is specifically used to assess the qi of the five zang and six fu organs, not the locations where the five zang and six fu organs reside.”

In addition, there are methods that do not distinguish between cun, guan, and chi, but rather divide them into floating, middle, and sinking, assessing the heart, liver, and kidneys on the left, and the lungs, spleen, and gate of life on the right, to assess the diseases of each organ. This method is used in critical conditions to seek the root cause. It can also be used for diagnosing the elderly, those with deficiencies, long-term illnesses, and postpartum conditions.

3. Methods and Precautions for Pulse Diagnosis

(1) Timing: The best time for pulse diagnosis is in the early morning. The Suwen: Essentials of Pulse states: “The diagnostic method is often performed at dawn, when the yin qi has not yet moved, the yang qi has not yet dispersed, food has not yet been consumed, the meridians are not yet full, the collaterals are balanced, and the qi and blood are not yet chaotic, thus it is possible to diagnose the pulse accurately.” This is because in the early morning, the patient is not influenced by food, activity, and other factors, and the internal and external environments are relatively quiet, allowing for easier identification of the disease pulse. However, this does not mean that pulse diagnosis cannot be performed at other times. Wang Ji believes: “If there is illness, it can be diagnosed at any time, and there is no need to be restricted to dawn.” In general, it is required to have a quiet internal and external environment during pulse diagnosis. Before diagnosis, the patient should rest for a moment to calm the qi and blood, and the examination room should also be kept quiet to avoid external influences and fluctuations in the patient’s emotions, which is beneficial for the physician to perceive the pulse patterns. In special circumstances, one should diagnose the patient at any time and place without being bound by these conditions.

(2) Positioning: The patient should be seated or lying flat, with the arms positioned level with the heart, the wrists straight, palms facing up, and supported on a cushion at the back of the wrist to facilitate pulse diagnosis. Incorrect positioning can affect the local qi and blood circulation, thus influencing the pulse patterns.

(3) Finger Technique: The physician and patient sit side by side, using the left hand to examine the patient’s right hand and the right hand to examine the patient’s left hand. When diagnosing the pulse, first place the middle finger on the inner side of the high bone of the palm to assess the guan pulse, then use the index finger to assess the cun pulse in front, and the ring finger to assess the chi pulse behind. The three fingers should be arched, with the fingertips aligned, using the finger pads to touch the pulse body, as the finger pads are more sensitive. The spacing of the fingers should correspond to the patient’s height; taller individuals should have wider spacing, while shorter individuals should have closer spacing. Once the correct location is determined, the three fingers should apply pressure simultaneously, referred to as total pressure. To focus on a specific pulse pattern, one can also use one finger to press on a specific pulse, such as slightly lifting the middle and ring fingers when examining the cun pulse; lifting the index and ring fingers when examining the guan pulse; and lifting the index and middle fingers when examining the chi pulse. In clinical practice, total pressure and single pressure are often used in combination.

For pediatric pulse diagnosis, the one-finger (thumb) method can be used to assess the guan pulse without dividing into three parts, as the cun-kou area in children is short and does not allow for three fingers to be placed, and they are often uncooperative due to crying.

(4) Lifting, Pressing, and Searching: This is a technique used during pulse diagnosis to explore pulse patterns by varying the pressure and movement of the fingers. Shui Boren in Diagnosis Essentials states: “The key to holding the pulse has three aspects: lifting, pressing, and searching. Light pressure is called lifting, heavy pressure is called pressing, and moderate pressure is called searching. When first holding the pulse, light pressure is used to assess it; if the pulse is felt between the skin, it indicates yang, and is associated with the organs; if the pulse is felt beneath the flesh, it indicates yin, and is associated with the liver and kidneys. If the pressure is neither light nor heavy, and is moderate, the pulse felt between the blood and flesh indicates a harmonious response, associated with the spleen and stomach. If the floating, middle, and sinking pulses are not felt, then searching is required; if they are faintly felt, it indicates a hidden pulse. This applies to all three parts.” Light pressure on the skin is called lifting, also known as floating or light touch; heavy pressure on the muscles and bones is called pressing, also known as sinking or heavy touch; moderate pressure that is both light and heavy is called searching. Therefore, during pulse diagnosis, it is essential to pay attention to the changes in pulse patterns between lifting, pressing, and searching.

Additionally, when the three parts of the pulse show discrepancies, one must gradually shift the finger position and search both internally and externally. Searching means to seek, not to take it as a given.

(5) Breathing: One inhalation and one exhalation is called one breath. During pulse diagnosis, the physician’s breathing should be natural and even, using the time of one inhalation and one exhalation to count the patient’s pulse rate, such as the rate of the pulse being slow, which is counted in breaths. Furthermore, it reminds the physician to remain calm and focused during pulse diagnosis, as stated in the Suwen: Essentials of Pulse: “Holding the pulse has its principles; tranquility is essential.”

(6) Fifty Pulses: Each time the pulse is diagnosed, it must reach fifty beats. This means that the time spent pressing the pulse on each side should not be less than fifty beats. The significance is twofold: on one hand, it allows for understanding whether there are any irregularities in the pulse during the fifty beats. However, if necessary, one can wait for the second or third set of fifty beats, with the goal of clarifying the pulse patterns. Therefore, each pulse diagnosis should last about 3-5 minutes; on the other hand, it reminds the physician not to be hasty in their diagnosis, as Zhang Zhongjing said: “If the pulse count does not reach fifty, a short-term diagnosis cannot be made, and the nine pulse patterns will not be clear… To observe life and death is indeed difficult.”

4. Normal Pulse

The normal pulse of a healthy person is described in the Suwen: Theory of Qi in the Normal Person: “With each inhalation, the pulse moves twice; with each exhalation, the pulse also moves twice. When breathing is steady, the pulse moves five times, and with a deep breath, it is said to be a normal person. A normal person does not have illness.” The characteristics of a normal pulse include having a pulse in all three parts, with a breath rate of four beats (with a deep breath, five beats, equivalent to 72-80 beats per minute), not floating or sinking, not large or small, calm and gentle, soft yet strong, with a consistent rhythm. The chi pulse should be taken with a certain strength and may vary normally with physiological activities and environmental changes. A normal pulse has three characteristics: stomach, spirit, and root.

Stomach: The stomach is the sea of water and grains, the foundation of postnatal life, and the source of the body’s nutrients and blood. Life and death depend on the presence of stomach qi; thus, “where there is stomach qi, there is life; where there is no stomach qi, there is death.” Therefore, the pulse is also based on stomach qi. The pulse pattern with stomach qi has many descriptions in ancient texts, such as the Ling Shu: Chapter on Endings and Beginnings: “When pathogenic qi comes, it is tight and rapid; when food qi comes, it is slow and harmonious.” Or it can be assessed by the stomach qi. In general, a normal pulse is neither floating nor sinking, neither fast nor slow, calm and gentle, with a consistent rhythm, indicating the presence of stomach qi. Even if it is a pathological pulse, regardless of whether it is floating or sinking, slow or fast, if it has a gentle and harmonious quality, it indicates the presence of stomach qi. Assessing the abundance or deficiency of stomach qi has certain clinical significance in determining the progression and prognosis of diseases.

Spirit: The pulse is valued for its spirit; the heart governs blood and houses the spirit. When the blood and qi are abundant, the spirit is strong, and the pulse naturally has spirit. The pulse pattern of spirit is soft yet strong; even a weak pulse should not be completely powerless to be considered spirited; a strong pulse should still carry a gentle quality to be considered spirited. In summary, the presence of stomach qi and spirit are consistent; thus, the pulse pattern with both stomach qi and spirit is the same.

Root: The kidneys are the foundation of pre-natal life and the driving force for the functional activities of the body’s organs and tissues. When kidney qi is sufficient, it reflects in the pulse pattern, indicating a strong root. The chi pulse should be taken with strength, indicating a strong root. If the kidney qi is still present during illness, and the foundation of pre-natal life is not exhausted, the chi pulse can still be felt, indicating that there is still vitality, as stated in the Pulse Classic: “Even if the cun-kou is absent, the chi is still not exhausted; with such a flow, there is no need to worry about extinction.”

A normal pulse varies physiologically in response to internal and external factors:

Seasonal Climate: Due to climatic influences, the normal pulse changes with spring being slightly wiry, summer being slightly surging, autumn being slightly floating, and winter being slightly sinking. In spring, although the yang qi rises, the cold has not yet completely dissipated, and the qi mechanism shows a constricted quality, hence the pulse is slightly wiry. In summer, the yang qi is abundant, and the pulse comes in strong but leaves weak, hence the pulse is slightly surging. In autumn, the yang qi desires to gather, and the pulse that comes in strong has diminished, feeling light and fine, hence the pulse is slightly floating. In winter, the yang qi is hidden, and the pulse comes in heavy and presses against the fingers.

Geographic Environment: The geographic environment can also influence the pulse pattern. In the south, where the terrain is low, the climate is warm, and the air is humid, the body’s muscles are relaxed, hence the pulse is often fine and soft or slightly rapid; in the north, where the terrain is high, the air is dry, and the climate is cold, the body’s muscles are tense, hence the pulse often appears heavy and solid.

Gender: Women’s pulse patterns are generally softer and slightly faster than men’s. After marriage and during pregnancy, women’s pulses often appear slippery and rapid, yet harmonious.

Age: The younger the individual, the faster the pulse; infants have a pulse rate of 120-140 beats per minute; children aged five to six have a pulse rate of 90-110 beats per minute; as age increases, the pulse pattern gradually becomes more harmonious. Young adults have strong pulses, while the elderly have weaker qi and blood, and their pulses are generally weaker.

Body Type: Individuals with larger body frames tend to have longer pulse locations; shorter individuals have shorter pulse locations. Thin individuals with less muscle often have floating pulses, while overweight individuals with thick subcutaneous fat often have sinking pulses. Commonly seen six pulses that are sinking and fine without any disease symptoms are called six yin pulses; pulses that are often large and strong without any disease symptoms are called six yang pulses.

Emotions: Temporary emotional stimuli can also cause changes in pulse patterns; for example, joy can harm the heart and cause a slow pulse, anger can harm the liver and cause a rapid pulse, and fright can disturb the qi and cause erratic pulses. When emotions return to calm, the pulse patterns also return to normal.

Activity and Rest: After intense exercise or long journeys, the pulse is often rapid; after falling asleep, the pulse is often slow; individuals engaged in mental labor often have weaker pulses than those engaged in physical labor. After eating, the pulse is often more vigorous; when hungry, the pulse pattern is slightly slower and weaker.

Additionally, some individuals may not have a pulse felt at the cun-kou but may feel it slanting from the chi towards the back of the hand, known as slanting pulse; if the pulse appears on the back side of the cun-kou, it is called reversed guan pulse, and pulses appearing at other locations on the wrist are considered physiological variations of pulse locations, which do not belong to pathological pulses.

Editor: Yang Wenjie, Physician Email: [email protected]