Pulse diagnosis, also known as “qiè zhěn” (切诊), is a method where the physician uses their fingers to palpate specific arteries on the patient’s body to experience the characteristics of the pulse, in order to understand health or disease and differentiate symptoms.

Video 1 – Principles of Pulse Diagnosis, Overview and Requirements

Video 2–Methods of Pulse Diagnosis and Characteristics of Normal Pulse

When discussing Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), people naturally think of the experienced TCM practitioners, who calmly squint their eyes and place three fingers on the patient’s wrist, pausing for a moment before telling the patient what illness they have and how to treat it. If the diagnosis is accurate, the patient will be amazed and convinced; if inaccurate, they may think poorly of TCM’s medical standards. Thus, pulse diagnosis has become a scale for some patients to measure the competence of TCM practitioners.

In clinical practice, it is common to encounter patients who, upon visiting, silently watch the doctor extend their hand, seemingly testing the accuracy of the pulse diagnosis. When the diagnosis is correct, they will smile and exclaim, “You are amazing!” However, if the diagnosis is incorrect, they may criticize the practitioner behind their back, questioning their competence. Is pulse diagnosis really that miraculous?

Tips: Pulse diagnosis should not be mythologized; no doctor can completely decipher all of a patient’s ailments through pulse diagnosis alone, not even the ancient physician Zhang Zhongjing from the Han Dynasty.

Why is pulse diagnosis so deeply rooted?

In fact, the entire diagnostic process in TCM involves only pulse diagnosis having direct contact with the patient. Of course, there are now some clinical examinations aided by instruments. Due to the physician’s extensive study of medical texts and understanding of TCM principles, they can analyze and judge the flow of qi and blood in the body through the pulse.

Pulse diagnosis is actually one of the most common methods in TCM diagnosis, part of the “four examinations” (望闻问切). Through this diagnostic method, we can understand the internal organs’ qi and blood flow. It assesses the condition of the internal organs based on the pulse’s speed, frequency, strength, and the shape of the blood vessels.

The famous Ming Dynasty physician Li Shizhen believed that pulse diagnosis was merely the last of the four examinations, a relatively clever diagnostic method. A good doctor must master all four examinations to fully understand the patient’s condition, rather than relying solely on this one.

Tips: A doctor’s diagnosis is akin to a police investigation; they must conduct a thorough examination of the entire scene, leaving no detail overlooked. This is called collecting information through observation, inquiry, and then making a judgment to determine if a crime has occurred.

Pulse diagnosis, also known as “qiè zhěn” (切诊), is a method where the physician uses their fingers to palpate specific arteries on the patient’s body to experience the characteristics of the pulse, in order to understand health or disease and differentiate symptoms.

Objectives and Requirements

1. Understand the clinical significance of pulse diagnosis.

2. Familiarize with the principles of pulse formation.

3. Understand the locations for pulse diagnosis and the three different methods of pulse diagnosis.

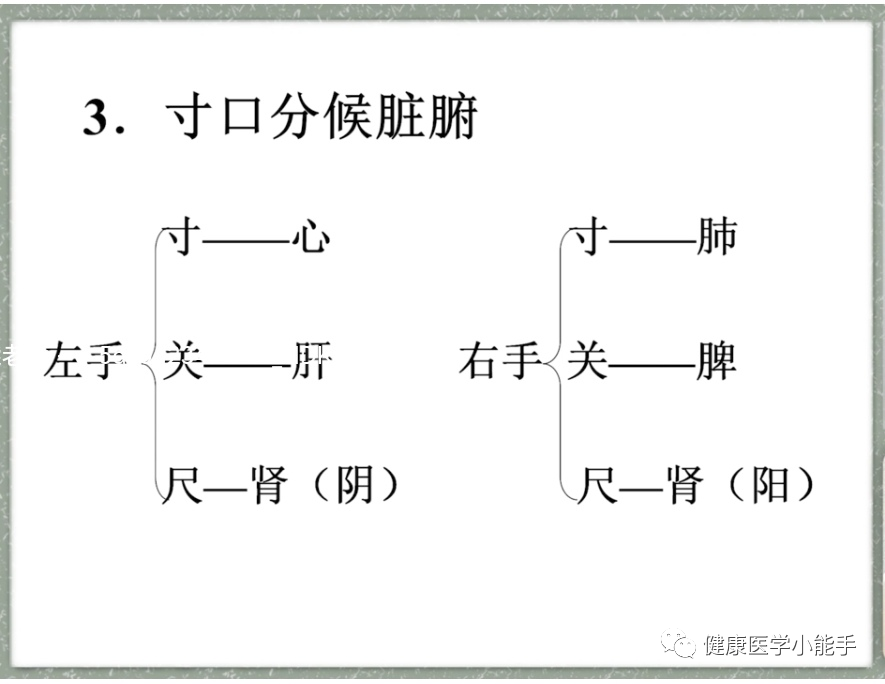

4. Master the cun-kou (寸口) diagnosis method, including the subdivisions and associated organs.

5. Master the methods of pulse diagnosis.

6. Correctly understand pulse characteristics and physiological variations.

7. Master the pulse characteristics of common diseases and their main conditions.

8. Understand the true zang pulse and various unusual pulses.

Tips: Traditional TCM differs from modern TCM in that modern TCM often combines Western medical examinations. In fact, pulse diagnosis is a process of determining conditions; Western medicine uses various instruments to scan internal organs, while traditional TCM relies on subtle observations of internal conditions, analyzing and deducing the nature and location of diseases.

Section 1: Overview of Pulse Diagnosis

1. Principles of Pulse Diagnosis

The heart is the main organ forming the pulse.

Heartbeats: The driving force behind pulse formation.

Pulse vessel contraction: An important factor in pulse formation.

Heart yin and yang: The basic conditions for maintaining a normal pulse.

Principles of Pulse Diagnosis

Every tissue and organ in the human body is composed of cells. Every part and corner of the body contains blood. Under normal circumstances, blood is stationary; why does it flow everywhere?

Because the heart provides the driving force, which in TCM is called “qi” (气) or “yang qi” (阳气). Blood is referred to as “yin blood” (阴血) or “yin liquid” (阴液), and blood is formed from bone marrow. Therefore, blood connects to every corner of our body; any cell lacking blood will die, let alone every organ. For instance, in patients with liver cancer, parts of the liver tissue may harden due to lack of blood supply and oxygen. Blood fills the entire vascular system (including veins and arteries), and blood runs to the radius, where the artery is located on the inner side of the radius. Thus, venous blood cannot pass deeper and must flow around the radius to the palm, making the pulse in this area relatively superficial.

Tips: Therefore, remember the principle of pulse diagnosis: when our heart’s strength is sufficient, its rhythm is calm, gentle, and powerful. The blood vessels’ blood flow reaches the radius, creating a slope, with three forces pushing the blood forward (forward, upward, and then circulating back to participate in the second upward push).

(1) The first force pushes forward at the cun-kou (寸口) position, with strength above.

(2) The second force pushes upward at the guan (关) position, acting like a checkpoint pushing upward; if it does not continue to push forward, it will sink down, lacking support.

(3) The third force, after pushing forward, circulates back to participate in the second upward push at the chi (尺) position.

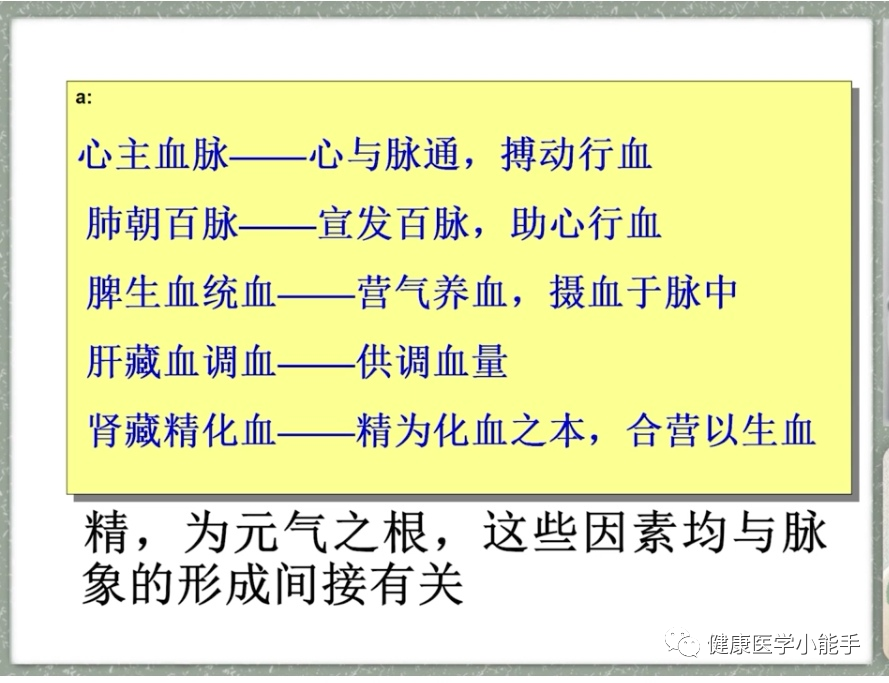

The heart governs blood vessels: blood and pulse are interconnected, and the heartbeat drives blood.

The lungs open to the hundred vessels: they disseminate the hundred vessels and assist the heart in circulating blood.

The spleen generates and controls blood: it nourishes blood and collects it in the vessels.

The liver stores and regulates blood: it supplies and adjusts blood volume.

The kidneys store essence and transform blood: essence is the foundation for blood transformation, combining with qi to elevate blood.

Essence is the root of original qi; these factors are all indirectly related to the formation of the pulse.

Tips: The heart governs blood vessels, and the pulse directly reflects the heart’s function and the presence of heart yang qi.

Qi and blood are formed by the functions of the spleen and stomach. The food and essence we consume are transformed by the spleen and then delivered to the lungs, where they are converted into qi and blood. When qi and blood are sufficient, the heart receives enough energy, allowing it to be continuously replenished. Thus, when qi and blood are abundant, it indicates that the functions of the spleen and lungs are also strong, and when the stomach qi is sufficient, the food essence can be initially processed and perfected. Additionally, we do not eat or replenish food essence at all times; during these times, some essence in the kidneys will be transformed into qi and blood to maintain the heart’s function, ensuring that the body’s overall functions operate normally.

2. Cun-Kou Diagnosis Method

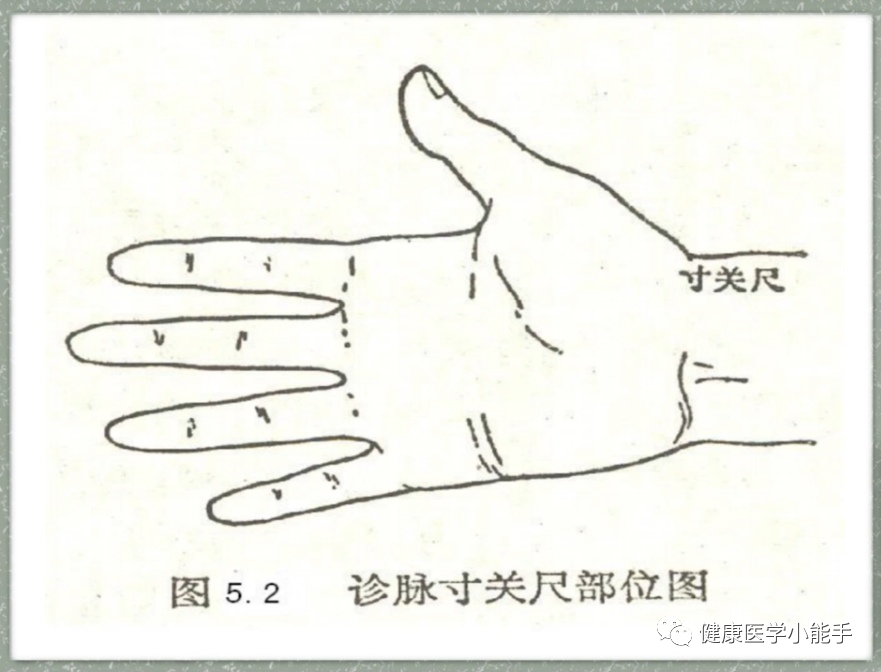

Meaning: The cun-kou (寸口) is a segment of the radial artery located on the inner side of the radial neck at the wrist (also known as the qi-kou or pulse-kou).

The cun-kou diagnosis method refers to the technique of palpating the radial artery at the inner side of the radial styloid process to assess the pulse’s characteristics and infer the physiological and pathological conditions of the body.

1. The cun-kou position is typically located at the inner side of the high bone at the back of the wrist, with the front being cun and the back being cun.

Cun (浮, 中, 沉)

Guan (浮, 中, 沉)

Chi (浮, 中, 沉)

Three divisions and nine positions, which correspond to the three divisions and nine positions in diagnostic methods.

2. Principles of Cun-Kou Pulse Diagnosis

(1) The cun-kou position is the major pulse point.

(2) The pulse qi is most evident at the cun-kou position.

(3) It can reflect the rise and fall of the ancestral qi.

(4) The cun-kou position is fixed and convenient for pulse diagnosis.

Tips: Our life comes from our parents, who provide us with our innate foundation, known as the fire of the life gate, located at the chi position (尺部) of the right hand (kidney yang). The fire of the life gate nourishes the spleen earth, thus at the guan position, there is a mutual generation relationship: spleen earth generates lung metal, lung metal generates kidney water, kidney water generates liver wood, liver wood generates heart fire, and heart fire in turn generates stomach earth, illustrating the continuous cycle of the five elements.

3. Methods of Pulse Diagnosis

(1) Timing

The best time for pulse diagnosis is early morning (before rising and before eating) when the dew has not yet formed, the yang qi has not yet moved, and the qi and blood are relatively balanced and slightly subdued. In reality, this may not always be possible, so generally, when taking the pulse, the doctor will ask the patient to sit in the examination room for five minutes to calm their mind and stabilize their emotions.

(2) Position

Patients can be in a supine position, with the heart and cun-kou at the same level, and the wrist should be straight with the palm facing up.

(3) Finger Techniques

1. Taking the Pulse

Select the fingertip: the sensitive part of the fingertip.

Gently place the fingers on the pulse ridge.

The finger pressure should be perpendicular to the pulse.

2. Positioning

(1) Standard positioning: same as body cun measurements.

(2) Simplified positioning: using the high bone to determine the guan position.

Position the fingers evenly at the back of the wrist’s high bone.

Tips: For body cun measurements: if the patient is tall, the distance between the three fingers is slightly wider; if the patient is shorter, the distance is closer.

3. Finger Movements

(1) Lifting and Pressing: The depth of finger movement.

Definition:

Light pressure upwards is called lifting, and lifting to the skin is called floating.

Heavy pressure downwards is called pressing, and pressing to the muscles and bones is called sinking.

Subtle lifting and pressing, seeking to understand, is called searching.

(2) Up and Down Movement

Definition: The up and down movement of the fingers.

Function: To perceive the length of the pulse shape and the vertical position of the pulse.

(3) Overall and Individual Pressing

Definition: The overall and sectional movements of the three fingers.

Function: Overall pressing – to assess the overall characteristics of the pulse and the relationship between the three sections; individual pressing – to assess the local characteristics of the three sections.

For pediatric pulse diagnosis, one can use the “one-finger (thumb) method” to determine the guan position without subdividing into three sections, as the pediatric cun-kou is short and does not allow for three fingers to determine the cun, guan, and chi, and they are often uncooperative and may cry.

(4) Calming

During pulse diagnosis, the patient’s breathing should be calm and even, facilitating counting and allowing the doctor to concentrate and focus on the pulse.

(5) Fifty Pulses

The pulse should be taken at least 50 times, with the pulse duration for both hands being around three minutes.

4. Elements of Pulse Characteristics (Position, Frequency, Shape, Force, Rhythm)

1. Pulse Position – The depth of the pulse beat, such as floating/sinking.

2. Pulse Frequency – The rate of the pulse, such as slow/fast.

3. Pulse Length – The range of the pulse beat, such as long/short.

4. Pulse Width – The size of the pulse beat, such as flooding/thin.

5. Smoothness – The fluidity of the pulse, such as slippery/rough.

6. Tension – The degree of tension in the pulse vessel, such as taut/relaxed.

7. Pulse Strength – The strength of the pulse, such as weak/strong.

8. Uniformity – Whether the pulse rhythm is even and whether the pressure is consistent.

Tips: Pulse position refers to the location of the pulse (shallow, medium, deep – floating, middle, sinking).

Pulse frequency refers to the number of beats within a specified time, using the calming method.

Shape refers to the length, thickness, softness, and hardness of the pulse.

Force refers to the strength of the pulse and the force of the blood.

Rhythm refers to whether the pulse beats regularly, whether it pauses after a few beats, and then resumes.

Section 2

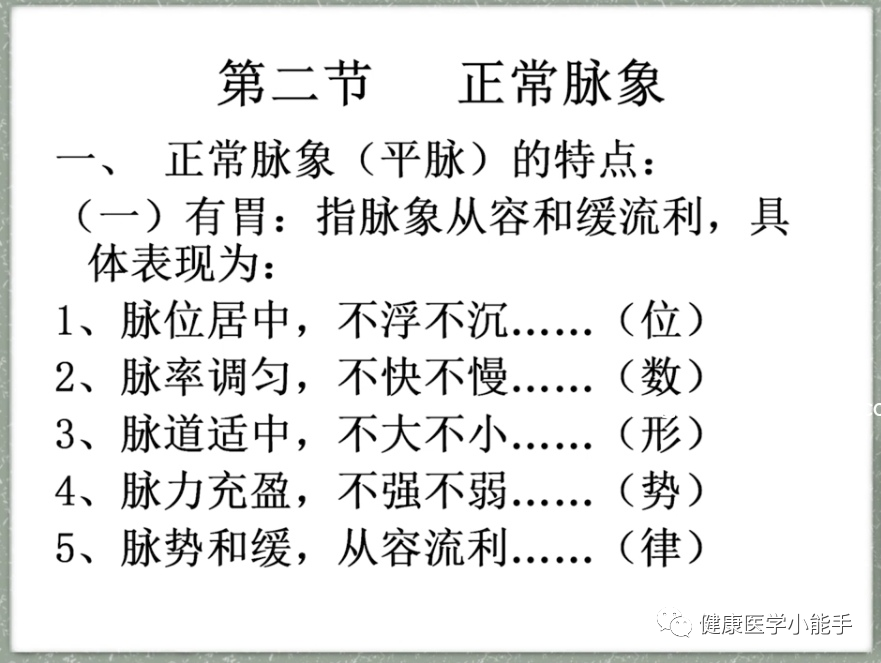

1. Characteristics of Normal Pulse (Ping Mai)

(1) Presence of Stomach

The pulse is characterized by a calm and smooth flow, specifically manifested as:

1. The pulse position is centered, neither floating nor sinking – position.

2. The pulse strength is balanced, neither fast nor slow – frequency.

3. The pulse channel is moderate, neither large nor small – shape.

4. The pulse strength is full, neither strong nor weak – force.

5. The pulse rhythm is calm, flowing smoothly – rhythm.

(2) Presence of Spirit

The pulse is strong and gentle, with a regular rhythm (force).

(3) Presence of Continuity – There is a continuous force pushing forward.

The chi pulse is strong, with a continuous sinking sensation, reflecting sufficient kidney qi.

The chi pulse reflects the kidneys; it is characterized by a strong chi pulse and a continuous sinking sensation.

2. Physiological Variations of Pulse Characteristics

1. Seasons: Spring – string-like, Summer – flooding (hook-like), Autumn – floating, Winter – sinking (stone-like).

Tips: More sunlight leads to stronger yang qi, resulting in more vigorous blood flow; less sunlight leads to a slight constriction of blood flow.

2. Emotions: When excited, the pulse is fast (frequency); when depressed, the pulse is slow or sinking.

3. Age: Children have small and fast pulses, young adults have smooth pulses, and the elderly often have string-like and hard pulses…

Tips: In children, one breath corresponds to seven beats.

4. Oblique Pulses: The pulse is not visible at the cun-kou but is directed obliquely from the chi to the back of the hand.

5. Reversed Guan Pulses: The pulse appears on the dorsal side of the cun-kou.