The emergence of Daoyin (导引) is closely related to the primitive medical practices of ancient times. The Neijing Suwen (《内经素问》) states that in ancient central China, due to the flat and humid terrain and abundant resources, the ancestors had a mixed diet and insufficient physical activity, leading to various ailments caused by stagnant Qi (气) and poor circulation.

These ailments were suitable for treatment through Daoyin, which involves shaking the muscles and bones and moving the joints. Therefore, Daoyin techniques primarily originated from the central region. When it comes to the specific movements of Daoyin, ancient practitioners often liked to imitate the lively and interesting movements of various animals, creating Daoyin techniques for health preservation.

In the Zhuangzi (《庄子》), such individuals are described: “Breathing in and out, expelling the old and taking in the new, like a bear hanging from a branch and a bird stretching its feet, all for the sake of longevity. This is the way of Daoyin, the practice of nurturing the body, favored by those like Pengzu (彭祖) who seek longevity.” This means that by utilizing the method of breathing, one expels waste from the body and inhales fresh air from the outside, mimicking the actions of bears hanging from branches and birds flying in the sky, all for the purpose of living longer, which is what practitioners like Pengzu cherished.

Pengzu, said to be named Qian Keng (钱铿), is believed to have lived during the Yin and Shang dynasties. His fief was in Pengcheng (彭城), and he was revered as the ancestor of health preservation practitioners, hence the name Pengzu. This mythical figure is said to have lived over 800 years due to his profound Daoyin skills.

The distinctive biomimetic characteristics of ancient Chinese health preservation techniques are rare in other ancient civilizations. This is directly related to the philosophical thoughts of ancient China, especially the Daoist perspective of returning to nature. In the eyes of ancient sages, only by freeing oneself from various internal and external desires and entering a completely natural state can one achieve physical and mental health. Thus, the wild animals that perfectly integrate with nature attracted people’s attention. They discovered that whether it was the leap of a tiger, the gallop of a horse, the antics of a monkey, the slithering of a snake, or the soaring of a crane, all were naturally formed without any artificiality.

Imitating these animals not only provided endless movement material for Daoyin but also helped practitioners psychologically enter a natural state that is crucial for health preservation. Today, when we face the thousands of biomimetic techniques in ancient Chinese health preservation and martial arts, we cannot help but admire the observational skills, imagination, and understanding of nature possessed by our ancestors.

During the Qin and Han dynasties, Daoyin techniques saw significant development, with more animal-imitation health practices emerging. In the Huainanzi (《淮南子》) by Liu An of the Western Han, besides “bear hanging and bird stretching,” it also mentions fu (凫服) bathing, jue (猿躩) movements, chi (鸱吃) gazing, and hu (虎顾) turning. What did Daoyin look like 2000 years ago?

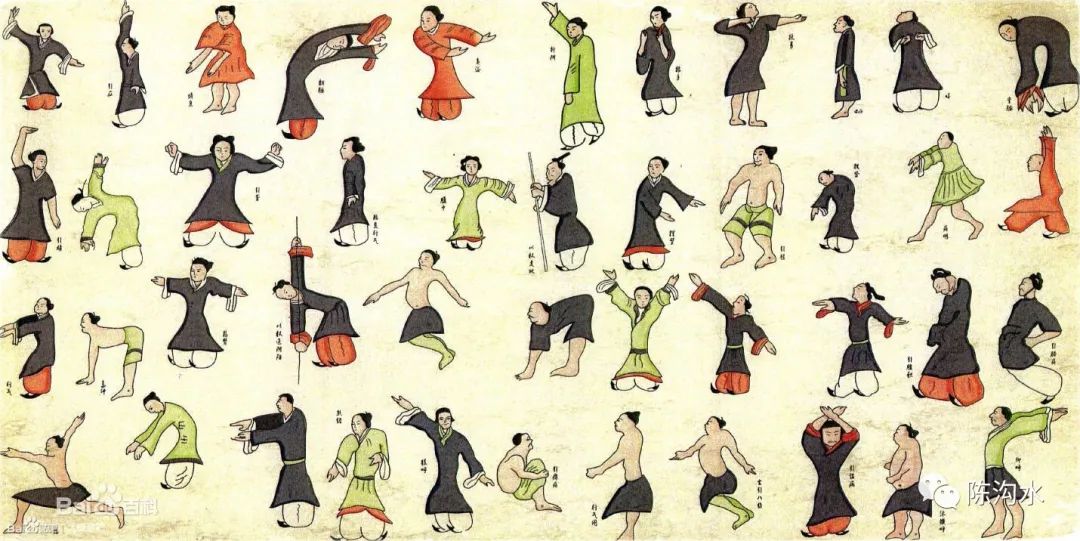

Today, we can only imagine based on historical texts until the discovery of a precious silk painting titled Daoyin Tu (《导引图》) in the Western Han tomb of Mawangdui in Changsha in 1973, which allowed us to see the true image of ancient Daoyin for the first time.

This painting depicts 44 individuals performing various Daoyin movements, all intricately colored. The practitioners include both men and women, young and old, with some dressed in long robes and others in short garments, even shirtless poor men, indicating that Daoyin had a very broad popular base and was loved by all social classes at that time.

The movements depicted can be categorized into three types: limb movements, breathing movements, and equipment movements. From the annotations beside each Daoyin technique, most movements are designed to treat specific ailments such as chest oppression, deafness, knee pain, chest and flank distension, and epidemic diseases. Some techniques are also designed to strengthen the body, promote Qi and blood circulation, and prevent diseases, such as “using a staff to connect Yin and Yang” and “looking up and breathing.” Notably, nearly half of the movements are derived from imitating wild animal actions, such as “hawk’s back,” “dragon climbing,” and “monkey bathing,” indicating that the important characteristic of biomimicry in ancient Chinese sports saw new developments during the Han dynasty.

The lack of connection between the various movements in this Daoyin painting suggests that by the Western Han period, Daoyin had not yet formed a coherent routine.

Why was there only this type of single-movement Daoyin at that time?

There may be two reasons: first, Daoyin techniques themselves were not yet mature enough to form routines; second, at that time, Daoyin was an important medical method, with each movement designed for a specific disease. To treat one disease, it was sufficient to repeatedly practice one movement, and there was no need to combine them.

Figure 4: Han Dynasty Daoyin Painting (Unearthed from the Western Han Tomb No. 3 in Mawangdui, Changsha in 1973)

In the late Eastern Han, Hua Tuo created the “Five Animal Frolics,” a significant event in ancient Chinese Daoyin. Hua Tuo lived during the Three Kingdoms period of Wei, Shu, and Wu, and was a famous physician known for his exceptional medical skills, proficient in internal medicine, surgery, gynecology, pediatrics, and acupuncture. Although the court invited him to serve as an official, he refused and spent many years traveling among the people, relieving their ailments across many places in present-day Anhui, Shandong, Henan, and Jiangsu. His treatments were often effective, earning him the title of divine physician. For the chronic headache suffered by Cao Cao, Hua Tuo could relieve the pain with just a few small silver needles, prompting Cao Cao to want to keep him by his side for constant use.

However, Hua Tuo was unwilling to serve only Cao Cao as a personal physician and ultimately met a tragic end. Hua Tuo was not only a physician but also an outstanding Daoyin practitioner who emphasized the importance of exercise for health, believing that the human body should engage in regular physical activity. Only through exercise can the food consumed be digested, blood circulation maintained, and diseases prevented. Therapy of All ThingsPublic AccountTipThis is like the axis of a door; as long as it is in motion, it will not rot.

Building on the foundations of previous Daoyin techniques, Hua Tuo created a self-care routine imitating the five animals: tiger, deer, bear, monkey, and bird, known as the “Five Animal Frolics” (Figure 5). While practicing the Five Animal Frolics, the practitioner alternates between the poised stance of a tiger ready to pounce, the galloping and turning of a deer, the rolling of a bear, the climbing and hanging of a monkey, and the soaring of a bird.These movements are both vigorous and gentle, fast and slow, engaging the entire body and providing excellent exercise benefits.

Hua Tuo told his disciple Wu Pu that the Five Animal Frolics could both treat diseases and strengthen the limbs. When feeling unwell, one should practice one of the movements, sweat a little, and then apply some powder on the body to feel refreshed and regain appetite. Wu Pu took his advice seriously and practiced the Five Animal Frolics diligently, and by the age of 90, he had clear vision, sharp hearing, and no tooth loss (from Book of the Later Han: Biographies of Alchemists: Biography of Hua Tuo).

The transition from the single-movement Daoyin for treating one disease, as seen in the Daoyin Tu, to the Five Animal Frolics, which enhances overall bodily function, marks a significant transformation in the history of Daoyin. Hua Tuo pioneered the direction of routine Daoyin, which not only increased the amount of exercise but also heightened people’s interest in practicing, integrating disease treatment, prevention, and health preservation into one, influencing the development of martial arts routines in the future.

Unfortunately, the Five Animal Frolics created by Hua Tuo were later lost. Centuries later, during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, the famous physician Tao Hongjing (公元456—536年) compiled the “Five Animal Frolics” in his work Record of Nurturing Life and Extending Life, which was later compiled by others. The emergence of the Five Animal Frolics marked the entry of ancient Chinese Daoyin techniques into a stage of routine development.

During the Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties, the health preservation expert Ge Hong (公元284—364年) also made outstanding contributions to ancient Daoyin and the entire health preservation practice. Ge Hong was well-versed in literature, history, philosophy, biology, geography, and astronomy, and had high attainments in medicine and health preservation. He was not only a scholar but also skilled in martial arts, excelling in archery and proficient with single knives and double halberds. Due to his military achievements, he was appointed as the General of Fubo, but later retreated to Mount Luofu to study alchemy and health preservation techniques.

Although Ge Hong vigorously promoted the consumption of elixirs for longevity, which caused some harm to health preservation practices, as a scholar, he also comprehensively analyzed and summarized the health preservation experiences of predecessors, proposing some influential theories and methods that promoted the development of health preservation techniques. His book Baopuzi (《抱朴子》) had a profound impact on later generations.

Before Ge Hong, health preservation practitioners had deep sectarian views, each believing their own methods were the best. Various schools of thought, such as Daoyin, Qigong (行气), nurturing the spirit (养神), and dietary practices (服食), mutually excluded each other. However, after studying various schools, Ge Hong proposed the idea of “integrating various practices,” meaning breaking down narrow sectarian views and combining different health preservation schools, such as nurturing the spirit, Daoyin, Qigong, and dietary practices, for comprehensive health preservation.

Ge Hong himself practiced this approach, emphasizing the consumption of elixirs, practicing Qigong, and placing great importance on Daoyin. His writings not only included biomimetic Daoyin techniques, such as Long Dao (龙导), Hu Yin (虎引), Xiong Jing (熊经), Gui Yan (龟咽), Yan Fei (燕飞), She Qu (蛇屈), Yuan Ju (猿踞), and Tu Jing (兔惊), but also advocated practicing in the morning and evening (from Baopuzi: Extreme Words), and recorded self-care massage techniques such as Knocking Teeth (叩齿), Gargling (漱咽), Eye Rubbing (摩目), Ear Pressing (按耳), and Face Rubbing (摩面), believing these actions could strengthen teeth, preserve hearing and vision, and enhance facial complexion (from Baopuzi: Inner Chapters).

Due to Ge Hong‘s efforts, various methods of ancient health preservation began to complement each other, gradually merging. More and more Daoyin techniques began to incorporate Qigong, massage, and other methods, and people increasingly paid attention to practicing multiple health preservation techniques to achieve comprehensive exercise benefits.

After Ge Hong, Tao Hongjing compiled the Daoyin Jing (《导引经》) in his work Record of Nurturing Life and Extending Life, preserving many valuable Daoyin materials from before the Sui and Tang dynasties. It mentions a set of Daoyin techniques performed in the morning, including Wolf Crouch (狼踞), Chi Gu (鸱顾), Stamping Feet (顿足), Crossing Hands (叉手), Stretching Feet (伸足), Eye Rubbing (熨眼), Eye Scratching (搔目), Face Rubbing (摩面), and Dry Bathing (干浴).

From the Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties onward, practicing Daoyin and Qigong became a social trend among the scholar-official class. The famous calligrapher, revered as the “Sage of Cursive Script,” Wang Xizhi (公元321—379年), practiced a Daoyin technique called “Goose Palm Play,” imitating the movements of a goose swimming, walking, spreading its wings, and foraging, which enhanced his arm strength. He also practiced Qigong for stillness. With such skills, Wang Xizhi achieved remarkable proficiency in calligraphy, with his strokes not only penetrating the paper but also deeply engraved into the wood. While people know that Wang Xizhi‘s excellent calligraphy came from his hard work, they may not realize that without Daoyin and Qigong, his calligraphy would not have reached such a high level.

The Sui and Tang dynasties were a peak period in ancient Chinese society, characterized by grandeur and inclusiveness of various schools of thought. During this time, health preservation techniques gradually converged, forming a profound system. Great Circulation refers to the acupuncture and Daoyin techniques that reached unprecedented prosperity during this period. In the medical book On the Sources and Symptoms of Diseases by Chao Yuanfang of the Sui dynasty, over 260 Qigong health preservation methods are listed.

In the Tang dynasty, the medical text Secret Essentials of the External Platform by Wang Tao recorded more than 300 Daoyin methods. It is worth mentioning the Tang dynasty physician Sun Simiao (公元581—682年), who was well-versed in health preservation techniques. Sun Simiao spent over 80 years practicing medicine among the people, refusing offers to serve as an official from the Sui Emperor and Tang Emperors, and conducted extensive research, closely integrating medicine with health preservation. He authored a series of works, including Essential Formulas for Emergency, Supplementary Formulas, and Formulas for Nurturing Life, which contain a wealth of Daoyin and Qigong content, including many Daoyin massage techniques such as Tianzhu Massage (天竺按摩法) and Laozi Massage (老子按摩法).

Sun Simiao was frail and sickly in his youth, but he lived to the age of 102 thanks to his superior health preservation techniques.

After the Tang dynasty, with the development of medicine, the theories and medical standards of Traditional Chinese Medicine reached unprecedented heights. Although Daoyin still played a role in treating diseases, its status in medicine significantly declined compared to before. Fire Techniques for Unlocking Therapy This situation prompted Daoyin health preservation techniques to actively evolve towards disease prevention, fitness, self-cultivation, and longevity. Therefore, from the Song dynasty onward, Daoyin techniques for health preservation developed rapidly.

Starting from the Song dynasty, ancient Chinese Daoyin techniques changed from being overly complicated and difficult to learn to becoming concise, systematic, and easy to practice. The new health preservation techniques could be mastered without spending much time, and the daily practice time was also short, indicating a deepening understanding of Daoyin and the ability to eliminate unnecessary or less useful content. The simplification of Daoyin made it easy to promote and popularize in society.

During the Song dynasty, three influential Daoyin techniques emerged. One was the “Twelve Month Sitting Exercises” created by Chen Tuan (陈抟) in the early Song dynasty, consisting of 24 movements practiced according to the 24 solar terms of the year; the second was the “Small Labor Technique” created by the Daoist Pu Qianguan (蒲虔贯), which is a health method primarily based on massage. Pu Qianguan believed that to maintain health, physical activity was necessary, but the amount of exercise should be small and not exhausting, hence the name “Small Labor Technique.”

This theory of fitness through small amounts of exercise has clear discussions in the Neijing: Suwen (《内经·素问》), and Hua Tuo‘s Five Animal Frolics also adhered to this principle, emphasizing that regular exercise is necessary but should not be excessive. Therapy of All ThingsPublic AccountTipThis fitness perspective has been passed down for thousands of years and has become an important principle of Chinese health preservation. This “Small Labor Technique” includes simple exercises and massages for the head, face, limbs, and trunk, which can be practiced whenever convenient, making it simple and easy to perform (from Pu Qianguan’s Record of Essential Health Preservation); the third Daoyin technique is the widely practiced “Eight Pieces of Brocade.”

The origins of the “Eight Pieces of Brocade” are not recorded in historical texts, but it actually underwent a long development process, absorbing the essence of various Daoyin and Qigong techniques. The “Eight Pieces of Brocade” embodies the efforts of countless ancient health preservation practitioners and began to circulate among the people in the late Northern Song dynasty, continuously improving during its transmission until it gradually took shape by the end of the Qing dynasty. The movements of the “Eight Pieces of Brocade” are simple and accompanied by easy-to-remember verses. The most widely circulated version of the verses is: “Two hands support the heavens to regulate the three burners, left and right draw the bow like shooting eagles, to regulate the spleen and stomach, one must lift one hand, five labors and seven injuries look back, shaking the head and wagging the tail to eliminate heart fire, seven bumps behind eliminate all diseases, clenching fists and glaring to increase strength, two hands grasp the feet to strengthen the kidneys and waist.”

This set of Daoyin techniques, although composed of only eight connected movements, provides comprehensive exercise for the body and integrates with Qigong, thus exercising both the internal and external aspects, making it truly concise and effective. Therefore, it is fitting that this health preservation method is named after colorful brocade.

The innovation of printing technology during the Song dynasty facilitated the publication of numerous books, leading to the organization and analysis of a vast amount of ancient health preservation materials, especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties. A series of works that emerged during the Ming and Qing periods elevated the ancient Daoyin health preservation techniques, which have a history of thousands of years, to a new level, such as Eight Notes of Following Life by Gao Lian, Essentials of Longevity by Leng Qian, Preserving Life and Protecting the Original by Gong Tingxian, Collection of Longevity by Hu Wenhui, Book of Longevity by Luo Hongxian, and True Transmission of Longevity and Illustrated Explanation of Internal Skills from the Qing dynasty.

Purely physical movement Daoyin and massage techniques became rare during the Ming dynasty. Daoyin increasingly focused on integrating physical movements, massage, and Qigong. For example, in the Ming dynasty, Zhou Lujing‘s Yimen Guangdu: Red Phoenix Marrow recorded the “Five Animal Frolics,” which not only changed the movements but also increased the requirements for Qigong practice.

Similarly, the “Eighteen Movements of Muscle-Tendon Changing Classic” created by Damo reflects this trend. This set of twelve movements combines breath regulation and physical activity closely, exercising both the internal and external aspects, with significant health benefits.

However, the “Eighteen Movements” differs from previous Daoyin techniques, which primarily aimed at disease treatment and prevention. Instead, it is characterized by its strong emphasis on physical strength and is closely related to martial arts. Therefore, practitioners of Shaolin Kung Fu often use the “Eighteen Movements” as a foundational skill, achieving “full of energy and strength, with strong bones and tendons.” This trend of closely integrating internal and external training directly led to the emergence of Taijiquan (太极拳) in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, which perfectly combines internal skills with martial arts techniques. It possesses the characteristics of Daoyin, the effects of Qigong, and maintains and enhances the combat functions of martial arts. It can be said that Taijiquan is also a crystallization of thousands of years of development in ancient Chinese health preservation techniques.

Recommended Previous Articles:

1、One Acupoint of Daoyin Can Achieve “Deep Regulation” of the Body

2、Using Fingers as “Moxibustion,” Inexpressibly Wonderful

In the process of promoting Traditional Chinese Medicine, there is always a sense of anxiety; one misstep could lead to violations, and one moment of inattention could result in account suspension. The revival of Traditional Chinese Medicine is undoubtedly a trend, and while the future is bright, the road ahead is indeed tortuous. We will persistently continue on this path, but how far we can go is truly uncertain. To prevent losing contact with the Therapy of All Things public account in the future, please click to add the following two public accounts, to avoid losing contact and getting separated.