1. Gallbladder

The gallbladder is the foremost of the six fu organs and belongs to the extraordinary organs. It is shaped like a pouch, resembling a gourd, and is attached to the liver’s small lobe. The gallbladder is yang and belongs to wood, while the liver is yin and also belongs to wood. The gallbladder stores and excretes bile, governs decision-making, and regulates the qi of the organs.

(1) Anatomy of the Gallbladder

1. Anatomical Position: The gallbladder is connected to the liver, situated between the small lobes of the liver, and has meridians that interconnect with the liver.

2. Structural Characteristics: The gallbladder is a hollow, pouch-like organ that stores bile, a pure, clear, bitter, yellow-green fluid. Therefore, it is referred to as the “zhongjing zhi fu” (中精之腑) in the “Lingshu: Ben Zang” and as the “qingjing zhi fu” (清净之腑) in the “Qianjin Yaofang”. The gallbladder’s anatomical structure is similar to that of other fu organs, thus it is one of the six fu organs. However, due to its physiological characteristics of storing essence, it also belongs to the extraordinary organs.

(2) Physiological Functions of the Gallbladder

It also interacts with the five zang organs in “storing essence and qi”.

1. Storage and Excretion of Bile: Bile, also known as “jing zhi” (精汁) or “qing zhi” (清汁), originates from the liver. “The residual qi of the liver leaks into the gallbladder, gathering to form essence” (from the “Mai Jing”). Bile is formed and secreted by the liver, then stored and concentrated in the gallbladder, and through the gallbladder’s excretory function, it enters the small intestine. Bile is formed by the transformation of the liver’s wood qi, and after eating, it fills the small intestine, pressing on the gallbladder to release its juice into the small intestine to aid in food digestion and waste elimination. If bile is insufficient, the essence cannot be separated, leading to pale and clean stools without yellow coloration (from the “Nanjing Zhengyi”). The liver and gallbladder both belong to the wood element, with one being yin and the other yang, complementing each other. “The gallbladder is the fu of the liver, belonging to wood, governing the elevation of clear and the descent of turbid, facilitating the middle earth” (from the “Yixue Jianeng”). Thus, the gallbladder also has the function of excretion, but its excretion relies on the liver’s qi to perform its duties.

The bile stored in the gallbladder is excreted due to the liver’s excretory function, entering the intestines to promote the digestion of food. If the functions of the liver and gallbladder are abnormal, the secretion and excretion of bile will be obstructed, affecting the digestive functions of the spleen and stomach, leading to symptoms of poor digestion such as loss of appetite, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. If damp-heat accumulates in the liver and gallbladder, causing the liver to lose its excretory function, bile overflows and saturates the skin, resulting in jaundice, characterized by yellowing of the eyes, skin, and urine. The qi of the gallbladder descends smoothly; if the gallbladder qi is obstructed, the qi mechanism may reverse, leading to symptoms such as bitter mouth and vomiting of yellow-green bitter fluid.

2. Governing Decision-Making: The gallbladder governs decision-making, referring to its role in the mental and cognitive processes of judgment and decision-making. The gallbladder’s role in decision-making is crucial for defending against and eliminating adverse effects from certain mental stimuli (such as great fright) to maintain and control the normal flow of qi and blood, ensuring the coordination of the organs. Thus, it is said: “The gallbladder is the official of central justice, from which decisions are made” (from the “Suwen: Linglan Mijian Lun”). Mental and emotional activities are related to the gallbladder’s decision-making function, as the gallbladder assists the liver in excretion to regulate emotions. When the liver and gallbladder work together, emotions are stable. A person with strong gallbladder qi is less affected by intense mental stimuli and recovers quickly. Therefore, it is said that strong qi in the gallbladder prevents evil from interfering. Those with weak gallbladder qi are more susceptible to adverse effects from mental stimuli, leading to conditions such as timidity, easy fright, insomnia, and vivid dreams, which can often be treated effectively by addressing the gallbladder. Thus, it is said: “The gallbladder is attached to the liver, complementing each other; even if the liver qi is strong, it cannot be without the gallbladder. When the liver and gallbladder work together, courage is achieved” (from the “Leijing: Zangxiang Lei”).

3. Regulating the Qi Mechanism of the Organs: The gallbladder is associated with the liver, assisting in the liver’s excretion to regulate the qi mechanism, thus maintaining the internal balance of the organs and the external balance of the muscles, allowing for smooth ascension and descent, and orderly interactions. When the gallbladder functions normally, all organs are easily stabilized, hence the saying: “All eleven organs depend on the gallbladder” (from the “Suwen: Liu Jie Zangxiang Lun”). This means that “all eleven organs rely on gallbladder qi for harmony” (from the “Zabing Yuanliu Xizhu”). The human body is a mechanism of ascending and descending qi transformation; when the liver qi is unobstructed and the qi mechanism is smooth, the qi mechanisms of the organs ascend and descend in an orderly manner, with balanced yin and yang, and harmonious qi and blood. The gallbladder is a fu, while the liver is a zang; in the relationship between zang and fu, the zang is primary and the fu is secondary. Why is it said that “the eleven organs depend on the gallbladder” rather than “the eleven organs depend on the liver”? Because the liver is yin wood, while the gallbladder is yang wood, representing the lesser yang. “Yang is the master, and yin is the subordinate” (from the “Suwen: Yin Yang Li He Lun”). Yin is the foundation of yang, and yang governs yin; thus, the gallbladder, being yang wood, is said to be the one that the eleven organs depend on.

In summary, the phrase “the eleven organs depend on the gallbladder” aims to illustrate that in cognitive activities, the liver governs deliberation, while the gallbladder governs decision-making. The liver and gallbladder mutually support each other, rather than suggesting that the gallbladder has the role of the “great master of the five zang and six fu organs.” The gallbladder’s decision-making must be guided by the heart to function normally.

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the Gallbladder

1. Gallbladder Qi Governs Ascension: The gallbladder is the lesser yang among the yang organs, inheriting the wood virtue of the east, belonging to jia wood, and governing the ascending qi of the lesser yang spring. Therefore, it is said that gallbladder qi governs ascension. The gallbladder’s governing of ascension is synonymous with the gallbladder’s nature of promoting smoothness, which is similar to the liver’s preference for smoothness and aversion to depression. Jiazi is the head of the five movements and six qi, corresponding to spring, and is the lesser yang among the yang. When the spring qi ascends, all things are at peace; this is a natural law. Humans are in harmony with heaven and earth; in the human body, the gallbladder governs jiazi, and gallbladder qi ascends and promotes smoothness, allowing the qi mechanisms of the organs to be harmonious. When gallbladder qi ascends normally, the qi mechanisms of the organs ascend and descend normally, thus maintaining their physiological functions. Therefore, it is said: “The gallbladder is the qi of the lesser yang spring; when the spring qi ascends, all things transform and stabilize; thus, when gallbladder qi ascends, the other organs follow. If gallbladder qi does not ascend, then symptoms such as nausea, diarrhea, and intestinal obstruction will arise” (from the “Piwai Lun: Pi Wei Xu Shi Zhuan Bian Lun”).

2. Preferring Tranquility: Tranquility refers to a state of calmness and serenity. The gallbladder is the abode of clarity, preferring tranquility and disliking disturbances. When tranquil and free from disturbances, gallbladder qi is neither rigid nor soft, inheriting the gentle qi of the lesser yang, thus fulfilling its proper function, and the bile is excreted in a timely manner, allowing for decision-making in the face of situations. If there is evil in the gallbladder, whether heat, dampness, phlegm, or depression, the gallbladder loses its clarity and tranquility, losing its gentle nature and becoming obstructed, leading to symptoms such as bitter vomiting, restlessness, palpitations, and insomnia, and in severe cases, fear as if one is about to be captured. Clinically, the use of Wending Decoction to treat restlessness, insomnia, bitter vomiting, and palpitations aims to restore the gallbladder’s tranquil and gentle nature to regain its proper function.

2. Stomach

The stomach is the organ that holds food in the abdominal cavity. Its shape is curved, connecting above to the esophagus and below to the small intestine. It is responsible for receiving and digesting food and is known as the warehouse of food essence and the sea of qi and blood. The stomach, along with the spleen, is often referred to as the foundation of postnatal life. The stomach and spleen both reside in the middle earth, but the stomach is dry earth and belongs to yang, while the spleen is damp earth and belongs to yin.

(1) Anatomy of the Stomach

1. Anatomical Position: The stomach is located below the diaphragm in the upper abdominal cavity, connecting above to the esophagus and below to the small intestine. The stomach cavity is referred to as the “wei wan” (胃脘) and is divided into three parts: the upper, middle, and lower sections. The upper part is the upper wan, which includes the cardia; the lower part is the lower wan, which includes the pylorus; the middle wan is the section between the upper and lower parts. The cardia connects to the esophagus, and the pylorus connects to the small intestine, serving as the passage for food entering and exiting the stomach.

2. Structural Characteristics: The stomach has a curved shape with a greater and lesser curvature. As stated in the “Lingshu: Pingren Juegu”, it is curved to receive food and has both a greater and lesser curvature. The “Lingshu: Chang Wei” also states: “The stomach is curved and bent”.

(2) Physiological Functions of the Stomach

1. The Stomach Governs the Reception of Food: Reception refers to the act of accepting and containing. The stomach’s function of reception refers to its ability to accept and contain food. Food enters through the mouth, passes through the esophagus, and is temporarily stored in the stomach; this process is called reception, hence the stomach is referred to as the “great warehouse” and the “sea of food essence”. “What humans receive qi from is food; what food enters is the stomach. The stomach is the sea of food essence” (from the “Lingshu: Yuban”).

“The stomach governs reception, thus it is the repository of the five grains” (from the “Leijing: Zangxiang Lei”). The physiological activities of the body and the transformation of qi, blood, and fluids depend on the nutrition from food, hence the stomach is also called the sea of food essence and qi. The stomach’s function of reception is the foundation of its function of digestion, and if the stomach has pathological changes, it will affect its reception function, leading to symptoms such as poor appetite, fullness, and discomfort in the stomach area.

The strength of the stomach’s reception function depends on the strength of the stomach qi, which reflects the ability to eat or not. If one can eat, the stomach’s reception function is strong; if one cannot eat, the stomach’s reception function is weak.

2. The Stomach Governs the Digestion of Food: Digestion refers to the initial digestion of food in the stomach, forming chyme. The stomach’s function of digestion refers to its ability to digest food into chyme. “The middle jiao is in the stomach, neither ascending nor descending, and governs the digestion of food” (from the “Nanjing: Thirty-First Difficulty”). The stomach receives food ingested through the mouth and allows it to stay in the stomach for a short time for initial digestion, relying on the stomach’s digestive function to transform food into chyme. After initial digestion, the refined substances are transported by the spleen to nourish the entire body, while undigested chyme descends into the small intestine for continuous renewal, forming the stomach’s digestive process. If the stomach’s digestive function is weak, symptoms such as stomach pain and belching of foul-smelling food may occur.

The functions of the stomach in reception and digestion must be coordinated with the spleen’s transportation function to be completed smoothly. Therefore, it is said: “The spleen is the earth (the earth is yin, while heaven is yang—author’s note). The earth assists the stomach qi in digesting food; if the spleen qi does not circulate, then the food in the stomach cannot be digested” (from the “Annotated Treatise on Cold Damage”). The spleen and stomach work closely together; “the stomach governs reception, while the spleen governs transportation; one receives and one transports” (from the “Jingyue Quanshu: Food and Drink”). This allows food to be transformed into essence, generating qi, blood, and fluids to nourish the entire body, hence the spleen and stomach are referred to as the foundation of postnatal life, the source of qi and blood generation. Therefore, it is said: “Humans rely on food and water as their foundation; thus, if one is deprived of food and water, one dies” (from the “Suwen: Pingren Qixiang Lun”).

Traditional Chinese Medicine places great importance on “stomach qi”, believing that “humans rely on stomach qi as their foundation”. When stomach qi is strong, all five zang organs are robust; when stomach qi is weak, all five zang organs are weak. With stomach qi, there is life; without stomach qi, there is death. The term stomach qi encompasses three meanings: first, it refers to the physiological functions and characteristics of the stomach. The stomach is the sea of food essence, with the functions of reception and digestion, as well as descending and facilitating. These functions and characteristics are collectively referred to as stomach qi. Since stomach qi affects the entire digestive system’s function, it is directly related to the body’s source of nutrition. Therefore, the presence or absence of stomach qi is crucial to human life activities and survival, holding significant importance in human life activities. Thus, in clinical treatment, attention must always be paid to protecting stomach qi. Second, it refers to the reflection of spleen and stomach functions in the pulse, where the pulse appears calm and moderate. Because the spleen and stomach digest food and absorb the essence of food to nourish the entire body, and the essence of food is transported through the meridians, the presence or absence of stomach qi can be reflected in the pulse. Clinically, the pulse of stomach qi is characterized by a calm and moderate rhythm, neither fast nor slow. Third, it generally refers to the essence of the human body. “Stomach qi is the qi of food, the qi of nourishment, the qi of movement, the qi of life, the clear qi, the defensive qi, and the yang qi” (from the “Piwai Lun: If the Spleen and Stomach are Weak, the Nine Orifices will be Unblocked”).

Stomach qi can be reflected in appetite, tongue coating, pulse, and complexion. Generally, normal appetite, normal tongue coating, a rosy complexion, and a calm and moderate pulse are considered signs of having stomach qi. Clinically, the presence or absence of stomach qi is often used as an important basis for judging prognosis; that is, with stomach qi, there is life; without stomach qi, there is death. The so-called protection of stomach qi actually means protecting the functions of the spleen and stomach. In clinical prescriptions, it is essential to remember “do not harm stomach qi”; otherwise, if stomach qi fails, all medicines will be ineffective.

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the Stomach

1. The Stomach Governs Smooth Descent: The stomach’s governing of smooth descent is in contrast to the spleen’s governing of the elevation of clear. The stomach’s governing of smooth descent refers to the characteristic of the stomach’s qi mechanism being unobstructed and descending. “When food is digested in the stomach, the residue is transmitted from the stomach’s lower mouth to the upper mouth of the small intestine” (from the “Yixue Rumen: Zangfu”). Food enters the stomach, and after initial digestion, it must descend into the small intestine, where the clear is separated from the turbid, with the turbid descending into the large intestine to be transformed into feces, thus ensuring the state of alternation between the stomach and intestines. This is accomplished by the stomach qi’s unobstructed descending function. Therefore, it is said: “When food enters, the stomach is full, and the intestines are empty; when food descends, the intestines are full, and the stomach is empty; the more empty and full, the more qi ascends and descends” (from the “Suwen: Five Zang Distinctions”). Thus, the stomach values smooth descent, and the downward movement is orderly. The theory of organ function in Traditional Chinese Medicine summarizes the physiological functions of the entire digestive system based on the ascending and descending functions of the spleen and stomach. The stomach’s function of smooth descent also includes the small intestine’s function of transmitting food residues to the large intestine and the large intestine’s function of transforming waste. The spleen should ascend to be healthy, and the stomach should descend to be harmonious; when the spleen ascends and the stomach descends, they coordinate to complete the digestion and absorption of food.

The stomach’s smooth descent is a prerequisite for the descent of turbid. Therefore, if the stomach loses its smooth descent, symptoms such as poor appetite, fullness and discomfort in the stomach, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and belching may occur. The spleen and stomach reside in the center, serving as the pivot for the body’s qi mechanism’s ascension and descent. Thus, if the stomach qi does not descend, it not only directly leads to disharmony in the middle jiao but also affects the smooth ascent and descent of the entire body’s qi mechanism, resulting in various pathological changes.

2. Preferring Moisture and Disliking Dryness: Preferring moisture and disliking dryness refers to the stomach’s preference for being moistened and its aversion to dryness and heat. The theory of qi in Traditional Chinese Medicine states: wind, cold, heat, fire, dampness, and dryness are the six qi that divide the three yin and three yang; that is, wind governs the jueyin, heat governs the shaoyin, dampness governs the taiyin, fire governs the shaoyang, dryness governs the yangming, and cold governs the taiyang. The three yin and three yang qi are also divided into the five movements; that is, the jueyin wind qi belongs to wood, the shaoyin heat qi belongs to fire, the shaoyang fire qi belongs to fire, the taiyin damp qi belongs to earth, the yangming dryness qi belongs to metal, and the taiyang cold qi belongs to water. “Above the yangming, dryness governs” (from the “Suwen: Tian Yuan Ji Da Lun”); this refers to the six qi dividing yin and yang, indicating that dryness governs the yangming, which refers to the theory of qi. Humans correspond with heaven and earth; in the human body, the yangming refers to the yangming meridian, which includes the foot yangming stomach meridian and the hand yangming large intestine meridian. Both the stomach and large intestine inherit the qi of dryness; “the human body inherits the qi of heaven and earth, thus there are the stomach and large intestine, both of which are repositories for the digestion of food; since they inherit the qi of dryness, they must digest and expel water” (from the “Shanghan Lun: Shallow Annotation and Correction, Volume Two”). Fire is dry, and water is moist; the yangming dryness must rely on the taiyin dampness to assist it, thus achieving the balance of water and fire, allowing the stomach to receive and digest food essence and descend the turbid.

Therefore, it is said: “The stomach and large intestine belong to the shen and you, respectively, with shen corresponding to the earth and you corresponding to metal, and in the four seasons, they correspond to the seventh and eighth months, which is the time for the use of dry metal. Heaven and earth are merely the qi of water and fire transforming into all things; when water and fire intersect, they evaporate into moisture; the interaction of moisture and dryness is the qi of water and fire that does not change. If fire does not evaporate water, then clouds and rain do not come; if water does not assist fire, then dew does not fall” (from the “Shanghan Lun: Shallow Annotation and Correction, Volume Two”). In summary, the stomach’s preference for moisture and aversion to dryness is primarily reflected in two aspects: first, “the stomach is a yang body that combines with yin essence; yin essence must descend” (from the “Four Sacred Heart Sources”). The stomach’s qi must descend, relying on the nourishment of stomach yin; second, the stomach’s preference for moisture and aversion to dryness is in harmony with the spleen’s preference for dryness and aversion to dampness, thus ensuring the dynamic balance of the spleen’s ascent and the stomach’s descent.

3. Small Intestine

The small intestine resides in the abdomen, connecting above to the pylorus, communicating with the stomach, and connecting below to the large intestine, including the ileum, jejunum, and duodenum. It governs the reception and transformation of food and the separation of clear and turbid. It is associated with the heart, belonging to fire and yang.

(1) Anatomy of the Small Intestine

1. Anatomical Position: The small intestine is located in the abdomen, with its upper end connecting to the pylorus, communicating with the stomach, and its lower end connecting to the large intestine at the ileocecal junction, serving as the organ for further digestion of food. The small intestine has meridians that connect with the heart, and the two are mutually interrelated, thus the small intestine and heart are complementary.

2. Structural Characteristics: The small intestine is a hollow tubular organ that is coiled and looped. “The small intestine is attached behind the spine, looping around and coiling, with its connection to the ileum (i.e., the large intestine) located externally above the navel, with sixteen loops” (from the “Lingshu: Chang Wei”).

The small intestine includes the ileum, jejunum, and duodenum.

(2) Physiological Functions of the Small Intestine

1. Governing the Reception and Transformation of Food: The small intestine’s function of governing the reception and transformation of food refers to its role in receiving and transforming food. Reception refers to the act of accepting and containing food, while transformation refers to the digestion and conversion of food into usable nutrients. The small intestine’s function of reception and transformation is primarily reflected in two aspects: first, the small intestine receives the food that has been initially digested and moved down from the stomach, serving as a container; second, the food that has been initially digested in the stomach must remain in the small intestine for a certain period for further digestion and absorption, transforming the food into nutrients that can be utilized by the body, with the refined substances emerging from it and the waste being sent down to the large intestine, thus performing the function of transformation. In pathology, if the small intestine’s reception function is disordered, transmission and transformation will stop, leading to qi mechanism dysfunction and resulting in abdominal pain. If the transformation function is abnormal, it can lead to digestive and absorption disorders, manifesting as abdominal distension, diarrhea, and loose stools.

2. Governing the Separation of Clear and Turbid: Separation refers to the process of distinguishing between clear and turbid substances. The small intestine’s function of separating clear and turbid refers to its role in further digesting the food that has undergone initial digestion in the stomach while simultaneously separating the refined substances from the metabolic waste. The clear refers to the essence of food, including the fluids generated from beverages and the refined substances from food, which are absorbed and then transported by the spleen to the heart and lungs, nourishing the entire body. The turbid refers to the residual waste from food, which is transmitted through the ileocecal junction to the large intestine, forming feces that are expelled through the anus. The remaining water is transformed through the kidney’s qi transformation, seeping into the bladder, forming urine, which is expelled through the urethra. “The bladder and kidneys are complementary, both governing water; water enters the small intestine, descends into the bladder, and flows through the yin, resulting in urination” (from the “Zhubing Yuanhou Lun: Various Lin Conditions”). Because the small intestine participates in the body’s water metabolism during the process of separating clear and turbid, it is said that “the small intestine governs fluids”. Therefore, Zhang Jingyue stated: “The small intestine resides below the stomach, receiving the water and food essence from the stomach and separating the clear and turbid; the water and fluids seep into the front, while the waste returns to the back, with the spleen transforming and ascending, and the small intestine transforming and descending, thus the transformation of food occurs” (from the “Leijing: Zangxiang Lei”).

The small intestine’s functions of reception and transformation, as well as the separation of clear and turbid, are the most important stages in the entire digestive process. In this process, the chyme is further digested, transforming food into clear (i.e., refined substances containing fluids) and turbid (i.e., waste containing residual fluids) parts, with the former relying on the spleen’s transportation to be absorbed and the latter descending into the large intestine. The small intestine’s digestive and absorption functions are often categorized under the functions of the spleen and stomach in the theory of organ function. The functions of the spleen and stomach in receiving and transporting food actually encompass all the content of modern digestive physiology and part of nutritional physiology. Therefore, it is said: “Humans receive food and water; the spleen transforms the refined essence into qi, while the small intestine transforms the waste and transmits it to the large intestine” (from the “Yiyuan”). The so-called “the spleen transforms the refined essence into qi and ascends” actually refers to the small intestine’s function of digestion and absorption. Thus, the symptoms of poor digestion and absorption in the small intestine fall under the category of spleen dysfunction and are often treated from the perspective of the spleen and stomach.

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the Small Intestine

The small intestine possesses the physiological characteristics of ascending clear and descending turbid: the small intestine transforms food and separates clear and turbid, converting food into refined and waste, with the refined relying on the spleen’s ascent to nourish the entire body, while the turbid relies on the small intestine’s descent to transmit to the large intestine. The ascent and descent are interdependent, and the separation of clear and turbid is the small intestine’s responsibility for receiving and transforming food. Otherwise, if the ascent and descent are disordered and the clear and turbid are not distinguished, symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal distension, and diarrhea may occur. The small intestine’s ascending clear and descending turbid functions are specific manifestations of the spleen’s ascending clear and the stomach’s descending turbid functions.

4. Large Intestine

The large intestine resides in the abdomen, with its upper opening at the ileocecal junction connecting to the small intestine and its lower end connecting to the anus, including the colon and rectum. It governs the transmission of waste and the absorption of fluids. It belongs to metal and is yang.

(1) Anatomy of the Large Intestine

1. Anatomical Position: The large intestine is also located in the abdominal cavity, with its upper segment referred to as the “ileum” (corresponding to the anatomical ileum and upper segment of the colon); the lower segment is referred to as the “broad intestine” (including the sigmoid colon and rectum). Its upper opening connects to the small intestine at the ileocecal junction, while its lower end connects to the anus (also known as the “lower extreme” or “po gate”). The large intestine has meridians that connect with the lungs, thus they are mutually interrelated.

2. Structural Characteristics: The large intestine is a tubular organ, appearing in a coiled and looped shape.

(2) Physiological Functions of the Large Intestine

1. Transmission of Waste: The large intestine’s function of transmission refers to its role in receiving the food residues that descend from the small intestine, forming feces, and expelling them through the anus. The large intestine receives the food residues from the small intestine, absorbs the remaining water and nutrients, forming feces that are expelled through the anus, representing the final stage of the entire digestive process, hence it is referred to as the “transmitting fu” and “transmitting official”. Therefore, the primary function of the large intestine is to transmit waste and excrete feces. The large intestine’s transmission function is closely related to the stomach’s smooth descent, the spleen’s transportation, the lung’s descending function, and the kidney’s storage function.

If the large intestine is diseased, the transmission will be abnormal, primarily manifesting as changes in the quality and quantity of feces and alterations in the frequency of bowel movements. If the large intestine’s transmission is abnormal, symptoms such as constipation or diarrhea may occur. If damp-heat accumulates in the large intestine, leading to stagnation of qi in the large intestine, symptoms such as abdominal pain, urgency, and dysentery with pus and blood may arise.

2. Absorption of Fluids: After the large intestine receives the food residues and remaining water from the small intestine, it reabsorbs some of the fluids, forming feces that are expelled. The large intestine’s function of reabsorbing fluids participates in regulating the body’s water metabolism, referred to as “the large intestine governs fluids”. This function of reabsorbing fluids in the large intestine is related to the body’s water metabolism. Therefore, the large intestine’s pathological changes are often associated with fluids. For example, if the large intestine is deficient and cold, it will be unable to absorb fluids, leading to mixed food residues and symptoms such as abdominal rumbling, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. If the large intestine is in a state of excess heat, it will consume fluids, leading to dry intestines and constipation. The majority of the water required by the body is absorbed in the small or large intestine, thus “the large intestine governs fluids, while the small intestine governs liquids; both the large and small intestines receive the nourishing qi from the stomach, enabling them to transport fluids to the upper jiao, irrigating the skin and nourishing the pores” (from the “Piwai Lun: The Five Zang and Six Fu Organs All Belong to the Stomach; If the Stomach is Weak, All Will Be Ill”).

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the Large Intestine

In the functional activities of the organs, the large intestine is constantly receiving the food residues descending from the small intestine and forming feces for excretion, demonstrating a state of accumulation and transportation coexisting, thus it is characterized by smooth descent and unobstructed transmission. Among the six fu organs, the large intestine is particularly emphasized for its function of transmission and smooth descent. If the large intestine’s transmission is abnormal, it may lead to the accumulation of waste and obstruction, hence the saying that “the intestines are prone to fullness”.

5. Bladder

The bladder is also known as the “clean fu”, “water repository”, “jade sea”, “pouch”, and “urinary bladder”. It is located in the lower abdomen, positioned lowest among the organs. It governs the storage and excretion of urine and is complementary to the kidneys, belonging to the water element and having a yang attribute.

(1) Anatomy of the Bladder

1. Anatomical Position: The bladder is located in the lower abdomen, beneath the kidneys and in front of the large intestine. It is positioned lowest among the organs.

2. Structural Characteristics: The bladder is a hollow, pouch-like organ. It has ureters above that connect to the kidneys and a urethra below that opens at the front yin, referred to as the “urinary orifice”.

(2) Physiological Functions of the Bladder

1. Storage of Urine: In the process of fluid metabolism in the human body, water and fluids are distributed throughout the body through the actions of the lungs, spleen, and kidneys, playing a role in moistening the body. After being utilized by the body, the “excess of fluids” descends to the kidneys. Through the kidneys’ qi transformation, the clear is ascended and the turbid is descended; the clear returns to the body, while the turbid is sent to the bladder, transforming into urine. Therefore, it is said: “The excess of fluids enters the bladder to become urine; urine is the excess of water and fluids” (from the “Zhubing Yuanhou Lun: Bladder Disease Conditions”), indicating that urine is transformed from fluids. The relationship between urine and fluids is often interdependent; if fluids are deficient, urine will be scant; conversely, if urine is excessive, it may lead to fluid loss.

2. Excretion of Urine: Urine is stored in the bladder, and when it reaches a certain capacity, through the kidneys’ qi transformation, the bladder opens and closes appropriately, allowing urine to be expelled from the urinary orifice in a timely manner.

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the Bladder

The bladder has the physiological characteristic of governing opening and closing. The bladder is the gathering place for the body’s fluids, thus it is referred to as the “fu of fluids” and the “official of the state”. The bladder relies on its opening and closing functions to maintain the coordinated balance of urine storage and excretion.

The kidneys are associated with the bladder, opening at the two yin; “the bladder is the official of the state, storing fluids; when qi transforms, it can be expelled. However, if kidney qi is sufficient, it can transform; if kidney qi is insufficient, it cannot transform. If the body’s qi does not transform, then water returns to the large intestine, leading to diarrhea. If the expulsion of qi is not transformed, it will obstruct the lower jiao, leading to urinary retention” (from the “Bihua Yijing”). The bladder’s functions of urine storage and excretion rely entirely on the kidneys’ functions of solidifying and transforming qi. The so-called bladder qi transformation actually belongs to the kidneys’ qi transformation. If the kidneys’ functions of solidifying and transforming qi are abnormal, the bladder’s qi transformation will be disordered, leading to difficulties in urination or urinary retention, as well as frequent urination, urgency, incontinence, and other symptoms; thus it is said: “If the bladder is not functioning properly, it leads to urinary retention; if it is not controlled, it leads to incontinence” (from the “Suwen: Xuanming Wuqing Pian”). Therefore, the bladder’s pathological changes are often related to the kidneys, and in clinical treatment of abnormal urination, it is often treated from the perspective of the kidneys.

6. San Jiao (Triple Burner)

The San Jiao is a unique term in the theory of organ function. The San Jiao refers to the upper, middle, and lower jiao, collectively known as one of the six fu organs, and is the largest fu among the organs, also referred to as the external fu or solitary organ. It governs the ascending and descending of various qi and the circulation of water and fluids, belonging to fire in the five elements and having a yang attribute.

(1) Anatomy of the San Jiao

Historically, there has been a debate over whether the San Jiao has a tangible form or not. Even among those who believe it has a form, there is still no unified view on its essence. However, there is basic agreement on the understanding of the San Jiao’s physiological functions.

As one of the six fu organs, the San Jiao is generally considered to be a large fu distributed in the thoracic and abdominal cavities, with the San Jiao being the largest and unmatched, hence the term “solitary fu”. As Zhang Jingyue stated: “The San Jiao is indeed a fu; it exists outside the organs, within the body, encompassing all the organs, a large fu of one cavity” (from the “Leijing: Zangxiang Lei”).

Regarding the San Jiao’s form, as an academic issue, it can be further explored; however, this issue is not the main focus of the theory of organ function itself. This is because the concept of organs in Traditional Chinese Medicine differs from the anatomical concept of organs; Traditional Chinese Medicine categorizes the San Jiao as a separate fu not merely based on anatomy, but more importantly, based on the connections of physiological and pathological phenomena to establish a functional system.

In summary, the upper jiao is above the diaphragm, including the heart and lungs; the middle jiao is from the diaphragm to the navel, including the spleen and stomach; the lower jiao is from the navel to the two yin, including the liver, kidneys, large and small intestines, bladder, and uterus. Among them, the liver, according to its position, should be classified in the middle jiao, but due to its close relationship with the kidneys, both the liver and kidneys are classified in the lower jiao. The functions of the San Jiao actually encompass the functions of all the five zang and six fu organs.

(2) Physiological Functions of the San Jiao

1. Circulating Yuan Qi: Yuan qi (also known as original qi) is the most fundamental qi of the human body, originating from the kidneys, transformed from congenital essence, and nourished by acquired essence, serving as the foundation of the yin and yang of the body’s organs and the original driving force of life activities. Yuan qi circulates through the San Jiao and is distributed to the five zang and six fu organs, filling the entire body to stimulate and promote the functional activities of various organ tissues. Therefore, it is said that the San Jiao is the channel for the circulation of yuan qi. The movement of qi is the basic characteristic of life. The San Jiao’s ability to circulate yuan qi is the driving force for the qi transformation activities of the organs. Thus, the San Jiao’s function of circulating yuan qi is related to the overall qi transformation of the human body. Therefore, it is said: “The San Jiao is the qi of the three yuan of the human body… it governs the qi of the five zang and six fu organs, the channels of nourishment and defense, and the qi of the internal and external, upper and lower, and left and right” (from the “Zhongzang Jing”).

2. Unblocking Water Pathways: “The San Jiao is the official of drainage, from which the water pathways emerge” (from the “Suwen: Linglan Mijian Lun”). The San Jiao can “regulate the water pathways” (from the “Yixue Sanzi Jing”), controlling the entire process of water metabolism in the body, playing an important role in the water metabolism process. The body’s water metabolism is a complex physiological process involving multiple organs working together. Among them, the upper jiao’s lungs are the source of water, promoting the distribution and descending of water; the middle jiao’s spleen and stomach transform and distribute fluids to the lungs; the lower jiao’s kidneys and bladder vaporize and transform, allowing water to ascend to the spleen and lungs, and then participate in the body’s metabolism, with the excess forming urine to be expelled. The San Jiao serves as the pathway for the generation, distribution, ascent, and descent of water and fluids. When the San Jiao’s qi is functioning well, the meridians are unobstructed, and the water pathways are smooth. The San Jiao’s function of circulating water and fluids is essentially a summary of the functions of the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and other organs involved in water metabolism.

3. Running Water and Food: “The San Jiao is the pathway for water and food” (from the “Nanjing: Thirty-First Difficulty”). The San Jiao has the function of running water and food, assisting in the distribution of refined substances and the excretion of waste. Among them, “the upper jiao develops, disseminating the flavors of the five grains, nourishing the skin, filling the muscles, and moistening the hair” (from the “Lingshu: Jueqi”); the middle jiao “separates the waste, vaporizes the fluids, transforms the refined substances, and ascends to the lung meridians” (from the “Lingshu: Ying Wei Sheng Hui”); the lower jiao “forms waste and descends into the large intestine, following the lower jiao and seeping into the bladder” (from the “Lingshu: Ying Wei Sheng Hui”). The San Jiao’s function of running water and food, assisting in digestion and absorption, is a summary of the functions of the spleen and stomach, liver and kidneys, heart and lungs, and the large and small intestines in completing the digestion, absorption, and excretion of water and food.

(3) Physiological Characteristics of the San Jiao

1. The Upper Jiao is Like Mist: The upper jiao is like mist, referring to its role in disseminating defensive qi and distributing refined substances. The upper jiao receives the refined substances from the middle jiao’s spleen and stomach, and through the heart and lungs’ dissemination, it spreads throughout the body, exerting its nourishing and moistening effects, like the irrigation of mist. Thus, it is said that “the upper jiao is like mist”. Because the upper jiao receives the refined substances and distributes them, it is also referred to as “the upper jiao governs reception”.

2. The Middle Jiao is Like Steaming: The middle jiao is like steaming, referring to the spleen and stomach’s function of transforming water and food and generating qi and blood. The stomach receives and digests food, and through the spleen’s transformation, it forms refined substances from food essence, which in turn generates qi and blood, and through the spleen’s ascending and transporting function, the refined substances are sent to the heart and lungs to nourish the entire body. Because the spleen and stomach have the physiological functions of digesting food and transforming refined substances, they are likened to “the middle jiao is like steaming”. Because the middle jiao transforms water and food into refined substances, it is said that “the middle jiao governs transformation”.

3. The Lower Jiao is Like a Drain: The lower jiao is like a drain, referring to the functions of the kidneys, bladder, and large and small intestines in separating clear and turbid and excreting waste. The lower jiao transmits the food residues to the large intestine, transforming them into feces, which are expelled through the anus, and the remaining water is transformed into urine through the qi transformation of the kidneys and bladder, which is expelled through the urethra. This physiological process has the tendency to unblock downward and excrete outward, thus it is said that “the lower jiao is like a drain”. Because the lower jiao unblocks the two excretions and expels waste, it is also referred to as “the lower jiao governs excretion”.

In summary, the San Jiao is related to the entire process of receiving, digesting, absorbing, distributing, and excreting food and water, thus the San Jiao is the channel for circulating yuan qi and running water and food, serving as a comprehensive function of the physiological functions of the body’s organs, being the “total commander of the five zang and six fu organs” (from the “Leijing: Zangxiang Lei”).

Appendix: The True Interpretation of Pulse Diagnosis for Beginners

Pulse diagnosis is based on the depth and position of the radial artery to assess the depth of the disease. The ancients relied solely on clinical experience and personal intuition, leading to various mystical discussions: “The method of combining color and pulse is highly valued by sages, and it is the key to treating diseases”; “The essence of color and pulse can communicate with the divine”. Modern Western medicine only uses it to identify numbers and assess the heart. The ancient pulse theories are often disregarded, but should we ignore the precise and appropriate aspects of pulse diagnosis and treatment? This article aims to eliminate the confusion caused by erroneous statements and enlighten contemporary understanding. It seeks to ensure that the method of pulse diagnosis is not limited to the heart, allowing for refined diagnosis to shine in the future. First, we will dispel misconceptions, and then present the true interpretation.

1. Misconceptions about Pulse Diagnosis

The method of pulse diagnosis in Traditional Chinese Medicine originated in the “Suwen”, was expanded by the Yue people, and was perfected by Shuhe. Since then, there have been many renowned figures. However, determining yin and yang, deficiency and excess under three fingers, and distinguishing between internal and external within a small area, while seemingly simple, is difficult to understand. The ancients relied solely on clinical experience without scientific interpretation, leading to many erroneous statements. This is a limitation of the times. Even today, if one still believes in these misconceptions, it is indeed perplexing. The confusion surrounding Traditional Chinese Medicine’s pulse theory that misleads later generations can be attributed to three main points:

First, the error in dividing pulse locations: The pulse is divided into three parts, which is why three fingers are used for pulse diagnosis. Using three fingers for pulse diagnosis facilitates distinguishing between pulse conditions. The characteristics of the pulse, such as tightness, deficiency, and size, cannot be clearly understood without using the three methods of floating (浮按), pressing (中按), and searching (深按). This is a very simple and clear matter. Yet, the ancients even matched the three parts to the three jiao, and the nine conditions to heaven, earth, and humanity (as seen in the “Suwen: Three Parts and Nine Conditions”), which, although not entirely unreasonable, is still a stretch. The most harmful misconception for future generations is the idea of matching organs to the three parts.

The division of the cun, guan, and chi is originally for convenience in pulse diagnosis. The ancients did not seek a clear understanding of the relationship between pulse and disease influence, and arbitrarily matched organs to the three parts, leading to confusion. The “Suwen”, “Nanjing”, and other ancient texts have already matched the five zang organs, but without distinguishing left and right. Since Wang Shuhe, there has been a clear division of left and right, matching them with the five zang and six fu organs. Here, we compare the theories of six schools:

Wang Shuhe, Li Gao, Hua Shou, Yu Jiayan, Li Shicai, Zhang Jingyue

Left Cun: Heart, Small Intestine; Left Guan: Liver, Gallbladder; Left Chi: Kidney, Bladder; Right Cun: Lung, Large Intestine; Right Guan: Spleen, Stomach; Right Chi: Kidney, Bladder, San Jiao, Heart, Small Intestine.

All six schools are renowned in the medical community, and if they have such contradictions in matching organs, can their theories still be trusted? Upon examining the “Qianjin Fang” and “Shanghan Lun”, there is no such theory; even the “Zixu: Four-Character Pulse Method” states: “The left governs the officials, and the right governs the fu”; it does not explicitly state that certain organs belong to certain parts. Therefore, Wu Caolu knew this and said: “Doctors name the pulse at the cun, guan, and chi, saying this is the heart pulse, this is the lung pulse, this is the liver pulse… this is not the case. The five zang and six fu organs are all part of the twelve meridians, and both hands’ cun, guan, and chi are all part of the taiyin pulse… they are the great meeting of the six pulses, used to assess the entire body”. Li Shizhen understood this and stated: “Both hands’ six parts are all lung meridians, specifically used to assess the qi of the five zang and six fu organs, not the places where the five zang and six fu organs reside”. He also said: “I often see doctors pressing between the two hands, pressing again and again, saying this organ is like this, that organ is like that, as if the organs reside between the two hands, which is a form of self-deception”. Zhang Shiwang understood this, and when asked about the confusion of distinguishing organs, he said: “Both are right and wrong; what seems right may not be right”. It is said: “Mountains and rivers can speak, but the buried teacher has no place to eat; organs can speak, but the doctor looks like earth”. This is the theory of matching organs to the three parts.

The ancients did not believe in matching organs to the three parts, but instead followed the theory of the “Nanjing” as a standard. The “Nanjing” states: “The upper part corresponds to heaven, governing diseases above the chest to the head; the middle part corresponds to humanity, governing diseases from the diaphragm to the navel; the lower part corresponds to earth, governing diseases from the navel to the feet”. According to this theory, the pulse’s upper, middle, and lower parts correspond to the body’s upper, middle, and lower parts. Later generations, such as Xu Chunfu’s “Ancient and Modern Medical System”, based their theories on this statement, claiming: “The cun part corresponds to diseases from the chest, heart, lungs, throat, and head; the guan part corresponds to diseases from the chest below the diaphragm to the lower abdomen; the chi part corresponds to diseases from the lower abdomen, waist, knees, shins, and feet, including the large and small intestines and bladder, all in the lower part”. Wu Hegao’s pulse theory, Danbo Yuanguan’s pulse theory, and others all adhere to this theory. However, based on our daily experience, this theory, while not absolutely correct, is still somewhat credible.

Second, the misconception that the pulse governs disease: Pulse diagnosis is one of the diagnostic methods, and the ancients placed it at the end of the four examinations, considering pulse diagnosis to be of lesser importance. Therefore, the purpose of pulse diagnosis is to verify the body’s deficiency and excess, the depth of the disease, the progression of the disease, the prognosis, and the strength of qi and blood. Beyond this, it cannot be known through pulse diagnosis. However, some absurd individuals, having blindly believed in the theory of matching organs to the six parts, also mistakenly insist that the pulse governs disease, claiming that a certain pulse in a certain part indicates a certain disease, making grand statements and drawing conclusions. The most absurd of all is to determine a person’s death date, gender, wealth, and poverty based solely on the pulse, as seen in the case of Peng Yongguang, which is truly unforgivable. This is why I cannot help but clarify.

The idea that the pulse governs disease originated in the “Suwen” and was greatly expanded by Wang Shuhe, who stated: “If the cun pulse is deep and weak, the person will surely fall ill”. “If the guan pulse is tight and slippery, it indicates a snake-like condition”; “If the chi pulse is deep and slippery, it indicates a white worm” (all from Wang’s pulse theory). To determine disease based solely on the pulse is laughable. The pulse is a superficial layer of the radial artery, one of the various arteries; if one can determine disease based on the radial artery, can one also determine disease based on the temporal artery or foot artery? Diseases are numerous, while the pulse has only about twenty types; to determine hundreds of diseases based on twenty types of pulses is unreasonable. As the condition changes, the pulse also changes. For example, in cases of diarrhea, one may often find a weak chi pulse. However, at the onset of diarrhea, one may also find a strong, rapid, or taut chi pulse, while after diarrhea, one may find a weak, deep, slippery, or absent pulse. Thus, a weak chi pulse cannot be generalized to indicate diarrhea. Similarly, in cases of tuberculosis with hemoptysis, one may often find a taut pulse, but in the early stages of tuberculosis, one may find a floating, rapid, or rapid pulse, while in the advanced stages, one may find a large, fine, urgent pulse. Therefore, a taut pulse cannot be generalized to indicate tuberculosis. Furthermore, individuals have different structures and endowments, and their responses to the pulse may also vary. Some may have a consistently deep and fine pulse throughout their lives, while others may have a very rapid and slippery pulse, and some may have a pulse that appears to be tied but remain healthy. Thus, determining disease based solely on the pulse is unreasonable. In summary, diagnosing diseases should rely on various signs combined with pulse diagnosis; it cannot be determined solely based on three fingers. “If one can combine color and pulse, one can achieve completeness”; the ancients clearly indicated this to us as the correct method.

Third, the confusion in classifying pulse patterns: The pulse theories of the ancients are exceptionally chaotic, and the most perplexing aspect is the classification of pulse patterns. The “Suwen” categorizes the twelve meridians as being the same on both sides, combining them with the yang qiao, yin qiao, governor vessel, and conception vessel to form twenty-eight pulses, but in reality, there are only twenty-four pulses. Gao Yangsheng divided them into twenty-four pulses based on seven surfaces, eight li, and nine pathways. Zhu Hong categorized them into twenty-one pulses by combining seven surfaces and eight li. Chen Wuze divided them into twenty-four pulses (with different names from Gao Yangsheng). Hua Shou divided them into twenty-six pulses. Li Shizhen divided them into twenty-four pulses. Li Zhongzi divided them into twenty-nine pulses. Zhang Huang divided them into fifteen pulses. Chen Xiuyuan divided them into eight pulses. Ke Qin divided them into ten pulses based on yin and yang. Zhang Jingyue divided them into sixteen pulses. Zhang Shiwang divided them into thirty-two pulses. The fact that the same pulse can be pressed with three fingers while the pulse patterns differ so greatly is indeed a strange matter. This is because the ancients did not clearly understand the true nature of the pulse.

The division of the pulse into floating and sinking indicates the high and low pressure of the pulse; the division of the pulse into slow and rapid indicates the number of pulse beats; the division of the pulse into tight and soft indicates the expansion and contraction of the pulse vessel; the division of the pulse into slippery and rough indicates the smoothness or blockage of blood flow; the division of the pulse into knot and intermittent indicates changes in the heart’s chambers. There are many pulse patterns, all of which can be categorized under these five categories. Based on these five categories, all confusing theories can be clarified.

Thus, for pulses with high pressure, it is said to be floating, rapid, leathery, or moving, indicating varying degrees; for pulses with low pressure, it is said to be sinking, fine, firm, or hidden, indicating varying degrees, totaling eight pulses, all distinguished by floating and sinking. For pulses with a high number of beats, it is said to be rapid (six beats), or fast (more than seven beats), while pulses with fewer beats are said to be slow (three beats) or moderate (less than four beats), totaling four pulses, all categorized by slow and rapid. For pulses with a tense vessel, it is said to be tight or taut, while pulses with a relaxed vessel are said to be soft or weak, totaling four pulses, all based on the analysis of the tension and relaxation of the pulse vessel. For pulses with a smooth wave (i.e., blood flow), it is said to be slippery, firm, or long, while pulses with a blocked wave are said to be rough, weak, or short, totaling six pulses, all categorized by slippery and rough to distinguish the smoothness or blockage of blood flow. If the heart chambers weaken or the valves do not close properly, the blood may intermittently flow into the radial artery, resulting in a rapid, knotty, or intermittent pulse, indicating a sign of impending heart failure. In total, there are four pulses, all of which indicate the heart’s condition. The above totals twenty-six pulses, encompassing all pulse patterns. If we summarize, we can focus on the ten pulses of floating, sinking, slow, rapid, slippery, rough, tight, weak, knotty, and intermittent. Although the above interpretations may be somewhat simplified, the true meaning of the pulse has been thoroughly summarized. Further exploration depends on diligent and thoughtful individuals.

2. The Relationship Between Pulse and Diagnosis/Treatment

Once the true meaning of the pulse is clear, let us discuss its relationship with diagnosis and treatment, which can be summarized in four points:

First, understanding the disease mechanism: There are countless diseases and symptoms, but if we summarize their essence, they can be categorized into the eight characters of yin, yang, deficiency, excess, internal, external, cold, and heat. By distinguishing these eight characters, one can discuss diseases, apply treatments, and use medications. To understand the disease mechanism, one must distinguish these. Any metabolic function that is hyperactive is yang, while any that is diminished is yin; any that is energetically active is yang, while any that is weak is yin; any that is robust is yang, while any that is insufficient is yin; any that is active is yang, while any that is reduced is yin; any pathological function that is active is yang, while any that is passive is yin. The corresponding pulse patterns for these are: floating, rapid, leathery, and moving pulses indicate high pressure, while sinking, fine, firm, and hidden pulses indicate low pressure; tense and taut pulses indicate yang, while weak and soft pulses indicate yin; rapid pulses indicate yang, while slow pulses indicate yin; and pulses that are abundant and smooth indicate yang, while those that are weak, fine, and short indicate yin. Moreover, if symptoms change, there may be a yang condition presenting with a yin pulse, indicating a turning point towards a negative outcome, while a yin condition presenting with a yang pulse indicates a good prognosis; this cannot be discerned without pulse diagnosis. Furthermore, cold and heat are not only determined by body temperature, nor are they merely synonymous with yin and yang (where cold is yin and heat is yang). Any body temperature exceeding thirty-seven degrees Celsius is considered heat, while any temperature below normal is considered cold. If a disease is progressing and a large amount of fluid is expelled (through vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, urination, or phlegm) or if heat is severe and cannot be expelled, it is considered heat; if the disease is stagnant and fluid output is reduced or cannot stop, it is considered cold. Fullness in the body or locally indicates heat, while anemia indicates cold. However, there are symptoms that appear to be heat but present with a yin pulse, and symptoms that appear to be cold but present with a yang pulse, which must also be discerned through pulse diagnosis. Thus, the pulse diagnosis is essential for understanding the disease mechanism.

Second, determining treatment methods: The path to treating diseases is to eliminate pathogens and support the righteous qi. When pathogens are rampant, they manifest as hyperactive pathological mechanisms, which the ancients referred to as excess conditions. When the righteous qi is strong, it can resist pathogens and is often seen in symptoms of vigorous expression, which the ancients referred to as yang conditions. When both pathogens and righteous qi are strong, they conflict with each other, often presenting with symptoms of high fever, severe pain, extreme cold, and intense thirst, which the ancients referred to as excess conditions. At this time, the pulse must exhibit characteristics of being rapid, taut, slippery, and numerous. If the pathogens have been eliminated, the pathological mechanism will shift to a physiological mechanism, and the pulse will be weak and slow. If the righteous qi is weak, the ability to resist disease will be insufficient, leading to weak symptoms and yin conditions. The corresponding pulse will be weak, slippery, and slow. If the pathogens are strong and the righteous qi is weak, or if the righteous qi is strong and the pathogens have been eliminated, the yang pulse will present with yin symptoms, and the yin pulse will present with yang symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish. The “Shanghan Lun” discusses the correspondence between pulse and symptoms in great detail. The ancients stated that a strong pulse may appear weak, while a weak pulse may appear strong; this is the case. Therefore, if both the symptoms and pulse are strong, aggressive treatment methods can be used; if both the symptoms and pulse are weak, strengthening treatment methods should be employed; if the person is weak but the symptoms are strong, the disease should be treated first; if the symptoms are weak but the person is strong, it will heal naturally. In determining treatment methods, if pulse diagnosis is not considered, how can one determine the treatment?

Zhang Jingyue stated: “The method of treating diseases does not exceed the pulse”. This is a wise saying!

Third, determining prognosis: The pulse and symptoms are the most clear indicators for determining prognosis. For example, in cases of stroke or convulsions, regardless of whether there is arching of the back, paralysis of the limbs, inability to speak, abdominal fullness, urinary retention, or constipation, a pulse that is slow, weak, and sluggish indicates a favorable prognosis. When the disease occurs, the vagus nerve in the medulla is excited, preventing the actions of various parts, which corresponds to the pulse, resulting in a slow, weak, and sluggish pulse. If the vagus nerve is paralyzed and cannot control the excitement of the pulse nerve, the pulse will present as rapid, large, and numerous. Thus, the severity of the brain disease can be inferred from the pulse. Therefore, a slow, weak, and sluggish pulse in brain diseases indicates a good prognosis, while a rapid, large, and strong pulse indicates a poor prognosis. In acute and chronic febrile diseases, if the body temperature continues to rise, it is essential to pay attention to the health of the heart. Therefore, a rapid and large pulse is favorable, indicating the heart’s health. Thus, the pulse theory states: “In febrile diseases, a floating and rapid pulse is favorable; a sinking, weak, and small pulse indicates a poor prognosis”. “In cases of heat, a rapid and large pulse is appropriate, while a weak and fine pulse indicates a poor prognosis”. “In cases of fever, a rapid pulse indicates a poor prognosis”. All of these are determined by the health of the heart.

When the body is filled with pathogens, it is urgent to expel them; a pulse that appears rapid and strong indicates a good prognosis, such as in cases of trauma, blood stasis, dysuria, jaundice, and swelling, where the body is filled with toxins that need to be expelled. If the pulse is weak and fine, it indicates a poor prognosis, as the pathogens are strong and the person is already weak. Furthermore, if the body has lost excessive fluids (which are also products of the disease), the righteous qi will be weak, and the disease will require elimination, presenting a slow, weak, and small pulse, as the pathological mechanism (i.e., physiological mechanism) shifts from hyperactivity to normal. For example, in cases of excessive sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea (or prolonged pus, postpartum blood loss), the pulse is often slow, weak, and small, indicating a favorable prognosis. If the pulse is rapid and strong, it indicates that the disease is still progressing. After excessive fluid loss, if the disease continues to progress, can life be sustained? Thus, it is a negative sign. Similarly, in cases of “reflux and vomiting, the pulse should be slippery and large”; in cases of “asthma and cough, the pulse should be floating and slippery”; indeed, a slippery pulse indicates strong digestive function (the ancients believed that a slippery pulse indicates stomach qi), and both diseases are chronic; only with good digestion can one maintain strength and have a natural chance of recovery.

In conclusion, if this article has been helpful to you, please consider scanning the QR code to show your appreciation.

Traditional Chinese Medicine Internal Treatment Course:

“The Simplest Classic Formula Online Class” one-on-one, from differentiation to using classic formulas, sharing everything!!! (Click to enter)

Traditional Chinese Medicine External Treatment Course:

“Hands-On Traditional Chinese Medicine” can treat diseases even with no foundation!!! (One-on-one teaching) (Click to enter)

Traditional Chinese Medicine Learning Mind Map Series:

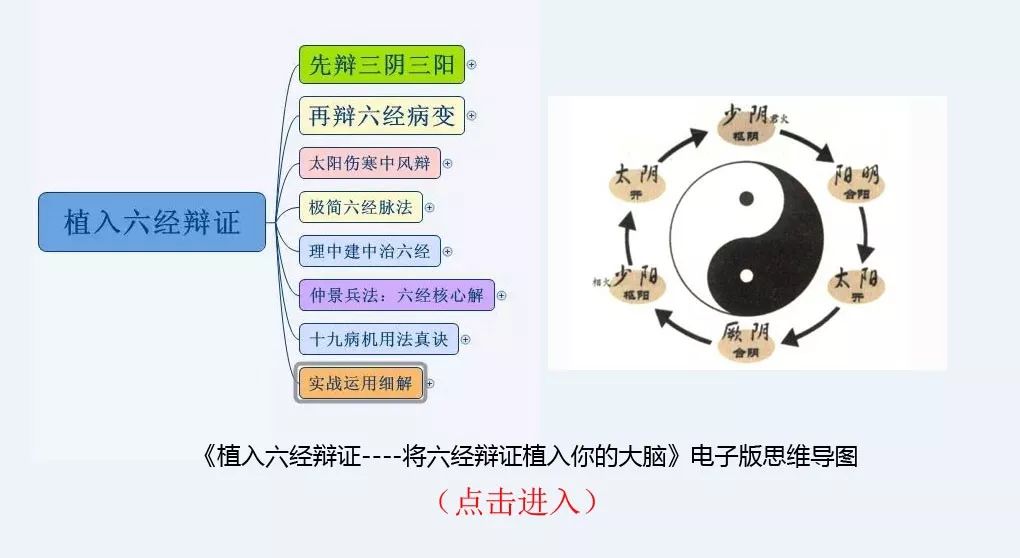

“Embedding Six Meridians Differentiation” —- “Embedding Six Meridians Differentiation into Your Brain” electronic version mind map (Click to enter)

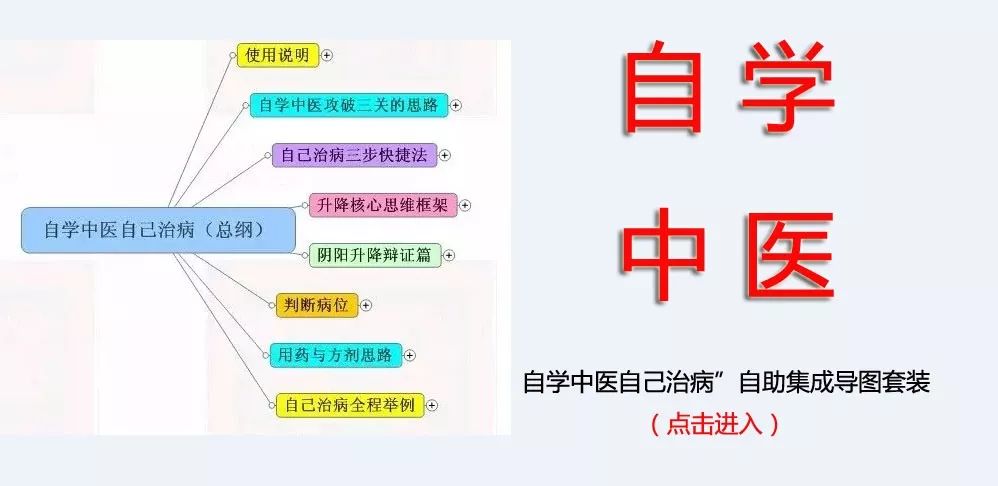

“Self-Learning Traditional Chinese Medicine to Treat Diseases” self-help integrated mind map set (Click to enter)

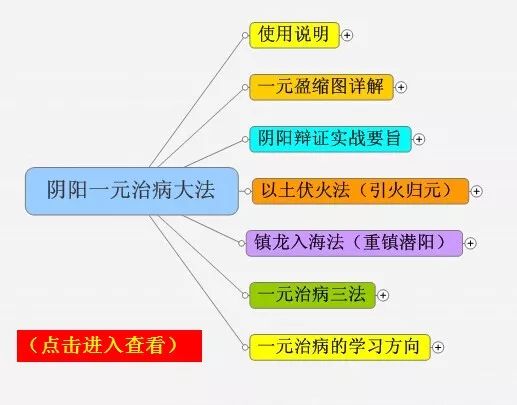

“Yin-Yang Unified Method of Treating Diseases” (Returning Complex Traditional Chinese Medicine to the One-Yuan Path) (Click to enter)

“Comprehensive Dialectical Map of Circular Motion” (Up and down, microcosmic yin and yang ascension and descent, organ positioning) mind map version (Click to enter)

If this article has been helpful to you, please consider scanning the QR code to show your appreciation.