We have previously discussed the corresponding 浮脉 (fu mai) (floating pulse). The main causes of floating pulse include the presence of pathogenic factors on the surface, deficiency of the middle qi leading to floating pulse, and excess yang leading to floating pulse.

This article will discuss 沉脉 (chen mai) (deep pulse).

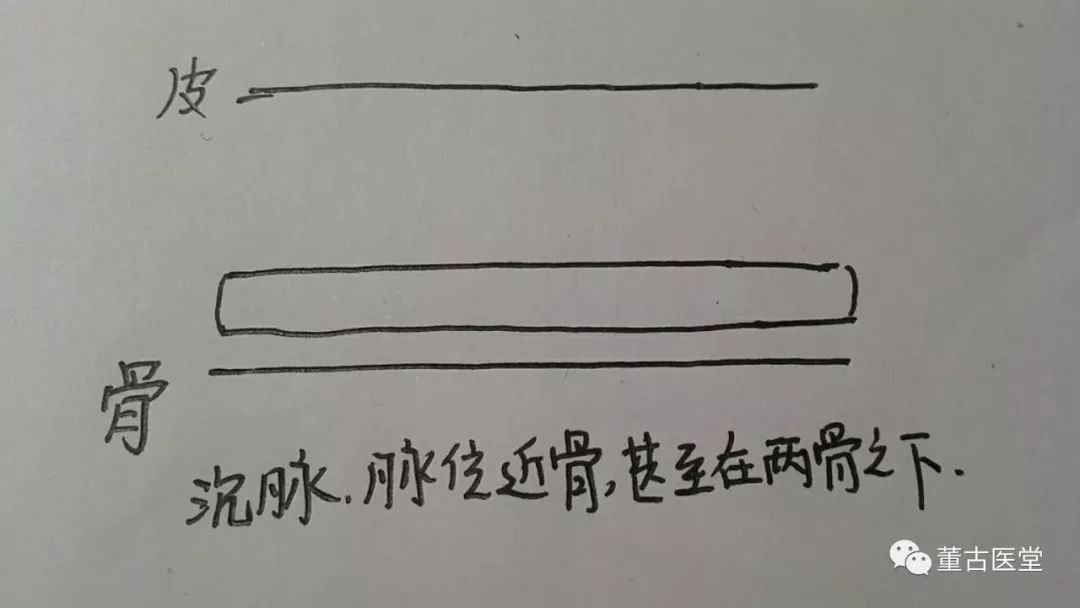

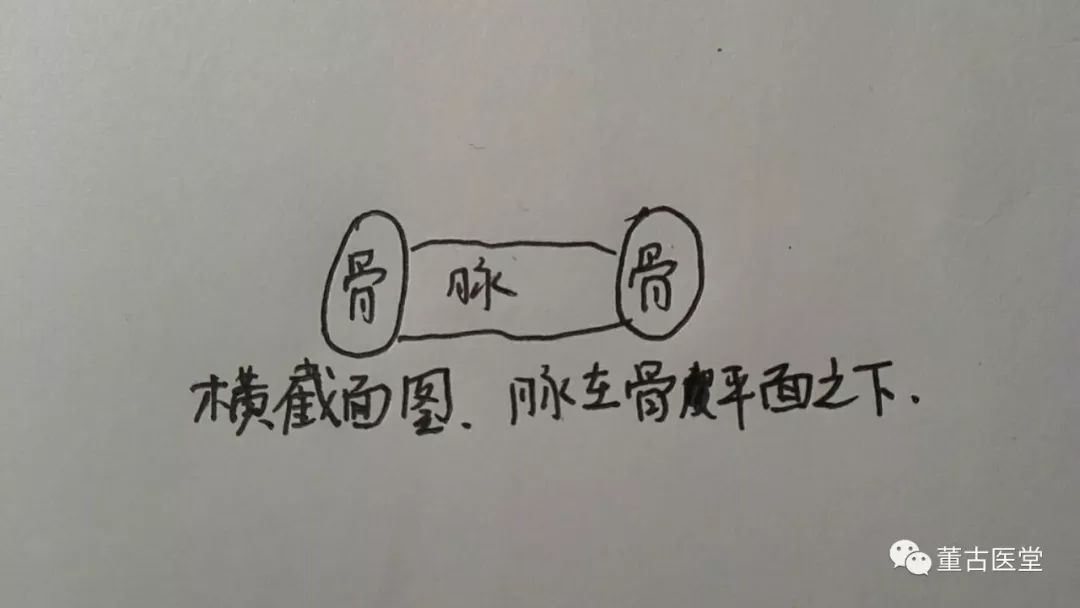

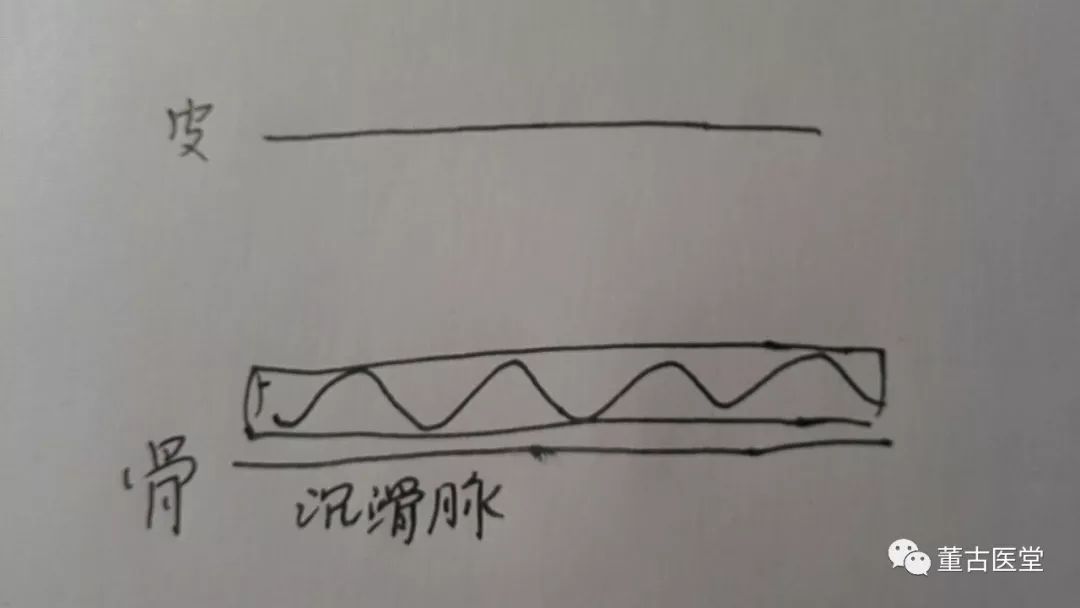

In simple terms, deep pulse refers to a pulse that is relatively deep in position, close to the bone, or even beneath the level of the bone.

Deep pulse close to the bone

Deep pulse beneath the level of the bone

Clinically, in some patients who are relatively thin with weak skin and muscles, the blood vessels may appear more prominent, making it difficult to determine whether the pulse is deep. In such cases, judgment should be made based on the level of the bone. Any pulse that is close to or beneath the level of the bone is considered a deep pulse.

Deep pulse is commonly seen in the following clinical conditions:

1: Deficiency of Middle Qi

Zhang Xichun proposed the concept of the descent of the great qi in his work 《医学衷中参西录》 (Yixue Zhongzhong Canxi Lu). This condition arises from sudden exertion or extreme anger, leading to the depletion of middle qi and subsequent descent of qi mechanism. He suggested using 升陷汤 (Shengxian Tang) (Rising and Descending Decoction) as a foundational formula for treatment. This condition represents a depletion of middle qi without accompanying pathogenic factors, a purely deficient and non-pathogenic clinical situation.

Zhang Xichun’s explanation of 升陷汤 (Shengxian Tang) is very insightful, as follows: it treats the descent of the great qi in the chest, with shortness of breath insufficient for inhalation; or labored breathing resembling wheezing; or breath about to stop, in imminent danger. Accompanying symptoms may include alternating chills and fever, dry throat and thirst, fullness and oppression in the chest, or mental confusion and forgetfulness, among various other symptoms that are difficult to enumerate. The pulse is characterized as deep, slow, and weak, particularly pronounced at the cun position.

Predecessor Zhang Xichun clearly pointed out the pulse characteristics of the descent of the great qi: overall weakness, with the cun pulse relatively more pronounced. This indicates a deficiency of qi leading to descent, a purely deficient and non-pathogenic condition.

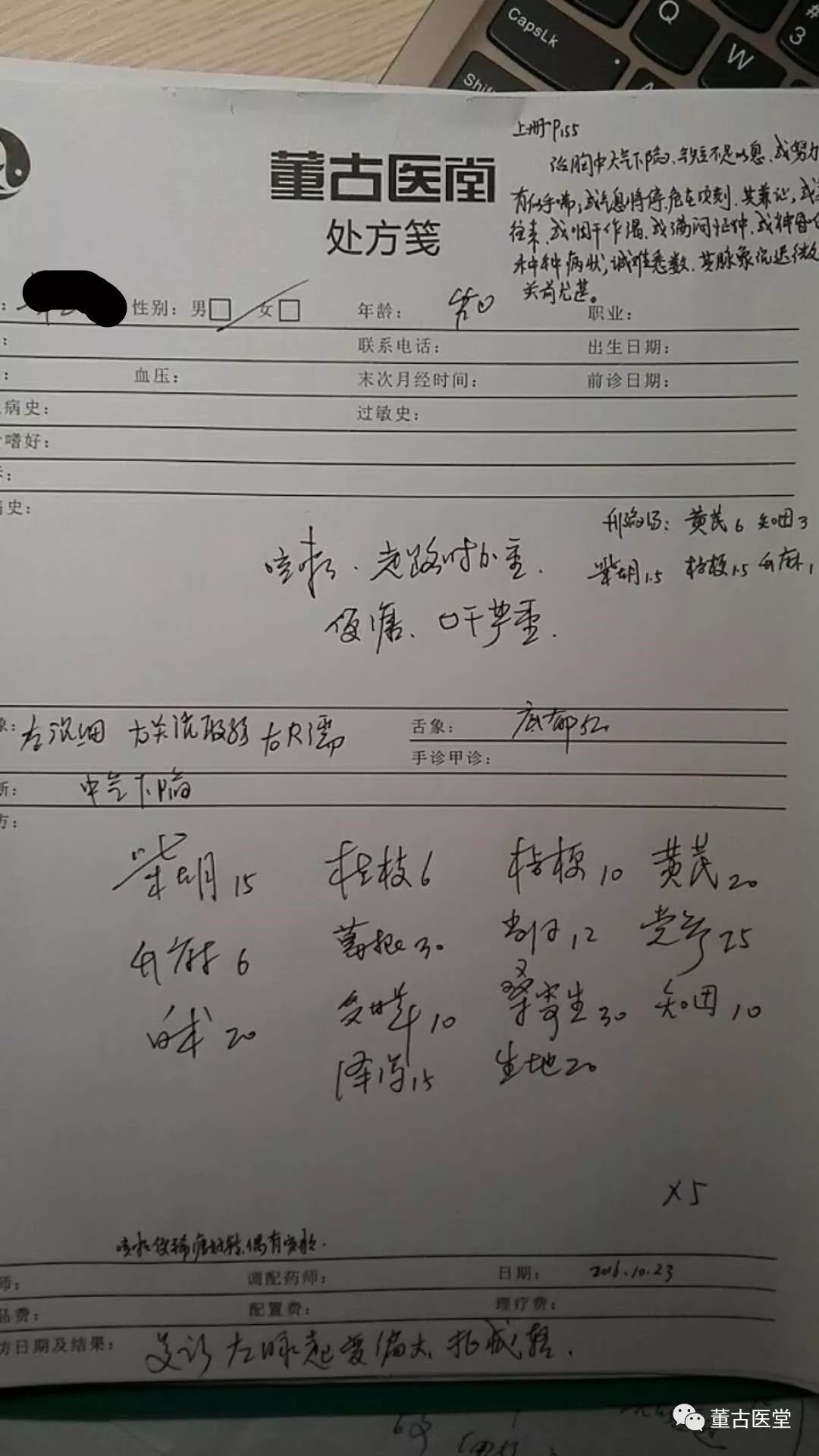

Now let’s look at a case.

This patient visited due to recurrent cough, initially consulting another doctor who prescribed a cough suppressant with minimal effect. Later, they came to me. The pulse was overall deep, with the left pulse thin and the right pulse weak.

The weak right pulse aligns with the characteristics of qi deficiency and descent. The symptoms were also typical. The cough worsened with walking, as walking consumed the great qi in the chest, necessitating a forceful cough to bring the qi up. Dry mouth and loose stools were manifestations of the failure of clear qi to rise.

For treatment, I used Zhang Xichun’s 升陷汤 (Shengxian Tang). The patient’s red tongue body indicated the presence of qi stagnation transforming into heat. Prolonged descent of qi can lead to stagnation and heat, a common clinical situation. I believe this is one reason why Zhang Xichun added 知母 (Zhi Mu) (Anemarrhena) to the formula. I also added a dose of 生地黄 (Sheng Di Huang) (Rehmannia), which in hindsight seems a bit superfluous.

After taking the medicine, the patient returned for a follow-up with significant improvement. The original formula remained unchanged, and after one more dose, they were basically well. Treating cough without using so-called cough suppressants reflects the essence of TCM syndrome differentiation and treatment.

2: Deficiency of Zheng Qi with Invasion of Pathogenic Factors

The body’s functions require the maintenance of qi. When qi is weak, functions will also weaken. Individuals who usually do not have significant phlegm-dampness may present with weakness as the main manifestation when middle qi descends, which is the aforementioned condition of descent of the great qi. However, for those who usually have significant phlegm-dampness, once the middle qi is injured, the phlegm-dampness will immediately manifest as a problem. I personally have a history of spleen deficiency with excess water. I remember one day at work, due to an overwhelming number of patients, I became overly fatigued. By noon, I suddenly felt dizzy and cold sweats, with an inexplicable accumulation of phlegm in my throat, making a gurgling sound, and it surged up to my throat. I quickly lay down to rest for a while before gradually feeling better. This was because the middle qi was excessively injured, and the pre-existing phlegm-water required the middle qi to maintain its operation. Now that the middle qi suddenly decreased, the phlegm-water could not be sustained, leading to an immediate surge of phlegm-dampness and pathogenic factors causing illness.

I also recall once eating improperly, consuming cold medicine that had not been heated. I immediately experienced abdominal pain and diarrhea, initially with sticky stools and a burning sensation in the anus. I remembered having eaten a lot of fried and greasy foods before. It was inevitable that after the middle qi was injured, the stomach and intestines lacked the strength to process these greasy foods, and could only expel them “while hot.” This shows that the body’s righteous qi can not only transform cold but also control heat. Therefore, those with weak spleen and stomach often experience heat when consuming fried foods and abdominal pain and diarrhea when consuming cold and cool foods; this is the reason. Initially, I did not take this diarrhea seriously. However, the next day, the diarrhea worsened, with dozens of watery stools, no heat, and no stickiness, with no burning sensation in the anus, accompanied by abdominal pain, bloating, and frequent belching, and a feeling of chest and rib oppression. I suddenly understood the words in 《伤寒论》 (Shang Han Lun) regarding 甘草泻心汤 (Gan Cao Xie Xin Tang): “In cases of cold damage and wind, if the physician purges, the patient will have frequent diarrhea, dozens of times a day, food will not digest, there will be thunder-like sounds in the abdomen, fullness and distension below the heart, dry retching, irritability, and inability to find peace. If the physician sees fullness below the heart and believes the illness is not resolved and purges again, the fullness will worsen. This is not due to heat accumulation, but rather due to deficiency in the stomach, with guest qi reversing upwards, hence causing fullness.” I also understood why some patients with coronary heart disease present with gastric distension and pain, and why some can be effectively treated with 泻心汤 (Xie Xin Tang) and 理中汤 (Li Zhong Tang) based on the Taiyin disease theory. When the condition changed to this extent, I felt I could not hold on any longer. So, I prepared a dose of 甘草泻心汤 (Gan Cao Xie Xin Tang). During the cooking process, the sweet and spicy aroma was very comforting. After taking the decoction, I felt extremely comfortable, and all symptoms immediately alleviated. The next day, the symptoms were basically resolved. I did not take any more medicine. This episode allowed me to fully understand the complete evolution from the initial invasion of pathogenic factors leading to 葛根芩连汤 (Ge Gen Qin Lian Tang) syndrome to the further injury of middle qi and the internal invasion of pathogenic factors leading to 甘草泻心汤 (Gan Cao Xie Xin Tang) syndrome. It also deepened my understanding that the occurrence of diseases in the human body is indeed the result of the interaction between external pathogenic factors and internal bodily factors. Different bodily states inevitably lead to different symptoms and outcomes.

Now let’s look at another case:

An elderly patient presented with sudden redness, swelling, and pain in the left foot. They reported that after donating blood, they immediately experienced sticky stools. Later, after a dinner with friends where they consumed a lot of shrimp and crab, and inadvertently caught a chill, they developed symptoms. Upon examination, the left foot and ankle were red, swollen, and extremely painful, making it impossible to walk.

This is clearly a case of damage to the righteous qi after blood donation, where the middle qi could not maintain balance, leading to an immediate overflow of water-dampness, hence the sticky stools. Therefore, while donating blood is a good deed, it is not suitable for everyone, especially in winter or when in poor health.

The patient’s examination results were as follows:

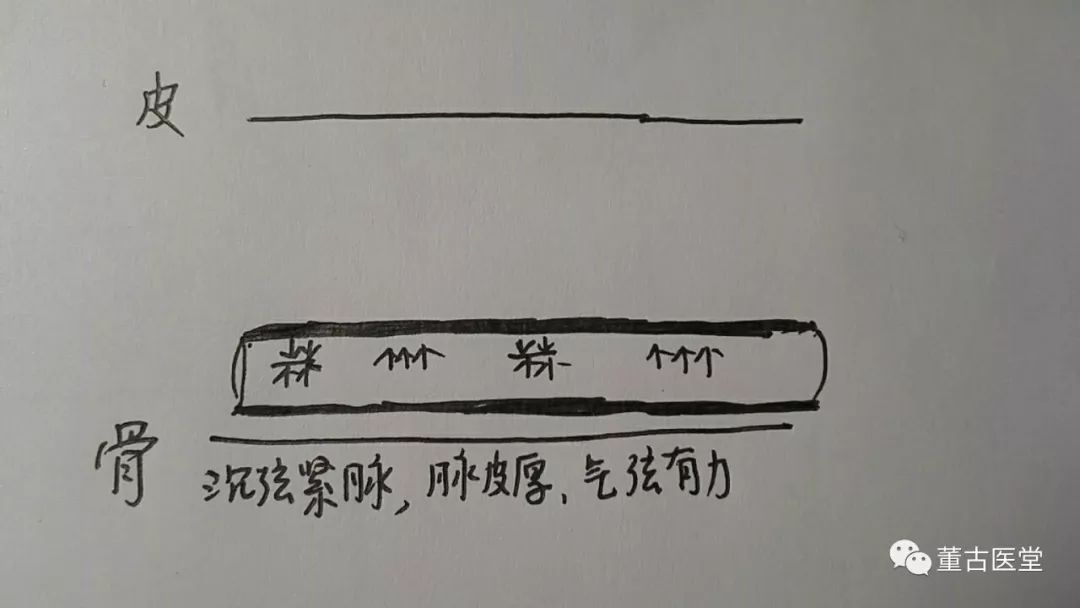

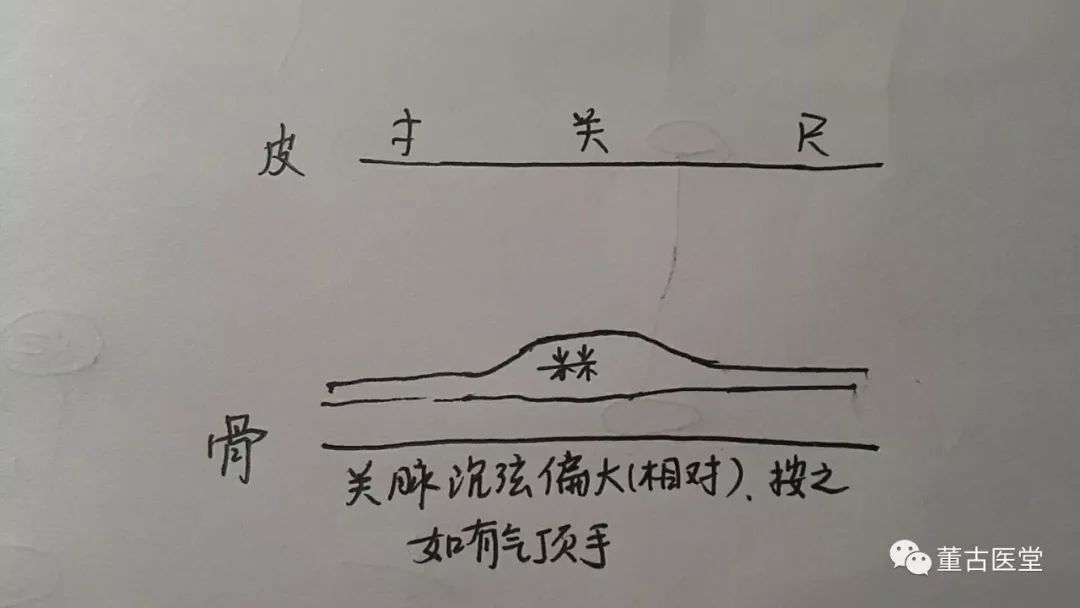

The patient’s pulse was deep, tight, and strong. As shown below:

Deep indicates injury to the middle qi with internal invasion of pathogenic factors. Tight indicates wind-cold, and strong indicates water-dampness. The strength reflects both the severity of the pathogenic factors and the fact that the righteous qi can still resist the pathogenic factors. This is a case where the pulse and symptoms correspond. Treatment is not difficult. If the pulse were floating, tight, and empty upon palpation, it would be troublesome.

For the prescription, I used 鸡鸣散 (Ji Ming San) to address the counterflow of the water-dampness. I also used 桂枝芍药知母汤 (Gui Zhi Shao Yao Zhi Mu Tang) to dispel wind-cold-dampness while nourishing the nutritive blood (as the contradiction between the injury to the nutritive blood and the excess of dampness was prominent after blood donation).

After taking three doses of medicine, the pain was significantly reduced, and the patient could walk, but still lacked strength.

Follow-up examination results were as follows:

The patient’s right three positions showed a change in the pulse from deep and tight to strong. The right cun pulse became weak, indicating a reduction in the counterflow of water-dampness and the essence of qi deficiency becoming apparent. The right guan pulse remained strong, combined with a thick white greasy tongue coating, indicating phlegm-dampness in the middle jiao. The prescription was adjusted to remove 鸡鸣散 (Ji Ming San) and use 桂枝芍药知母汤 (Gui Zhi Shao Yao Zhi Mu Tang) to address wind-cold-dampness, along with 槟榔 (Bin Lang), 草果 (Cao Guo), 豆蔻 (Dou Kou), and 紫苏叶 (Zi Su Ye) to address the accumulation of phlegm-dampness in the middle jiao. After taking three more doses, the patient reported being basically cured.

Deficiency of righteous qi with internal invasion of pathogenic factors is very common in clinical practice. After being exposed to external pathogenic factors, consuming frozen drinks, taking inappropriate so-called heat-clearing and detoxifying medications, being in air conditioning, or using medications improperly leading to excessive sweating or injury to yang qi can all result in damage to righteous qi and internal invasion of pathogenic factors. In 《伤寒论》 (Shang Han Lun), there are numerous cases where improper treatment leads to the depletion of fluids and qi, causing the internal invasion of pathogenic factors.

3: Qi Stagnation in the Interior

Clinically, the most common presentation is the 四逆散证 (Si Ni San Zheng) (Sini Powder Syndrome). The pulse is characterized by a deep, tight, and strong left guan pulse or bilateral guan pulses (qi string) as the main feature.

We say that among the string pulses, based on the specific situation of qi within the pulse, it can be divided into various types. The qi string pulse is one of them, representing qi stagnation.

The so-called qi string pulse is a tight pulse that feels strong against the fingers when pressed, similar to pressing on a rubber tube filled with high-pressure gas. If qi stagnation is on the surface, the qi string pulse will be floating and can be obtained. For treatment, use 青皮 (Qing Pi), 陈皮 (Chen Pi), 紫苏叶 (Zi Su Ye), and 紫苏梗 (Zi Su Geng) (light herbs) for treatment. If qi stagnation is in the interior, the qi string pulse will be deep and can be treated primarily with 四逆散 (Si Ni San) with modifications.

Now let’s look at a case to illustrate this.

The pulse is as follows:

This patient came for treatment due to amenorrhea. The patient had experienced amenorrhea for more than six months after consuming a large amount of genuine saffron. The left guan pulse was deep, tight, and strong, while the others were relatively thin and weak. Upon examination, the left chest and rib muscles were tense, with significant tenderness. For this patient, I sometimes used 十六味流气 (Shi Liu Wei Liu Qi), and sometimes used 四逆散 (Si Ni San) combined with 桂枝茯苓丸 (Gui Zhi Fu Ling Wan) and 归脾汤 (Gui Pi Tang). After several treatments, the patient’s menstruation returned, but the flow was dark and scant. Occasionally, there would be a delay of more than a month. Later, I chose to primarily use 疏肝汤 (Shu Gan Tang) as follows:

The patient reported that this formula was more effective. In retrospect, this all relates to the action of 四逆散 (Si Ni San). It is worth mentioning that the patient’s amenorrhea was caused by excessive consumption of saffron, and the more effective formula still contained safflower. This shows that excessive blood activation can lead to bleeding, and bleeding can lead to blood stasis, ultimately requiring blood activation to resolve the issue.

This patient later reported insomnia and waking at night, for which I used 血府逐瘀汤 (Xue Fu Zhu Yu Tang). The patient’s sleep improved, but they woke up at 5 AM. The guan pulse turned from tight to floating and vigorous. I then returned to using 疏肝汤 (Shu Gan Tang). Later, the patient did not return for follow-up, likely indicating that the results were not ideal. In fact, at this time, the qi stagnation in the interior had been eliminated, but there was still stagnation of qi and heat in the blood, at which point the formula should have been changed to 小柴胡 (Xiao Chai Hu Tang) combined with 生地 (Sheng Di), 茜草 (Qian Cao), and 丹皮 (Dan Pi). I will note this down as a reminder for myself.

4: Internal Pathogenic Factors Blocking

When there are pathogenic factors such as blood stasis, phlegm-water, or dryness blocking in the interior, the qi mechanism cannot be released outward, and the pulse will be deep. This situation needs to be distinguished from deficiency of qi with internal invasion of pathogenic factors. The former is due to internal pathogenic factors causing the qi mechanism not to rise, and once the internal pathogenic factors are eliminated, the pulse can become relaxed and not deep. The latter also has internal pathogenic factors, but it is accompanied by deficiency of middle qi, which will inevitably be accompanied by symptoms of deficiency such as pale complexion, fatigue, and cold intolerance. In treatment, caution is needed when using purgative methods, and attention must be paid to tonifying qi.

Now let’s illustrate this with a case.

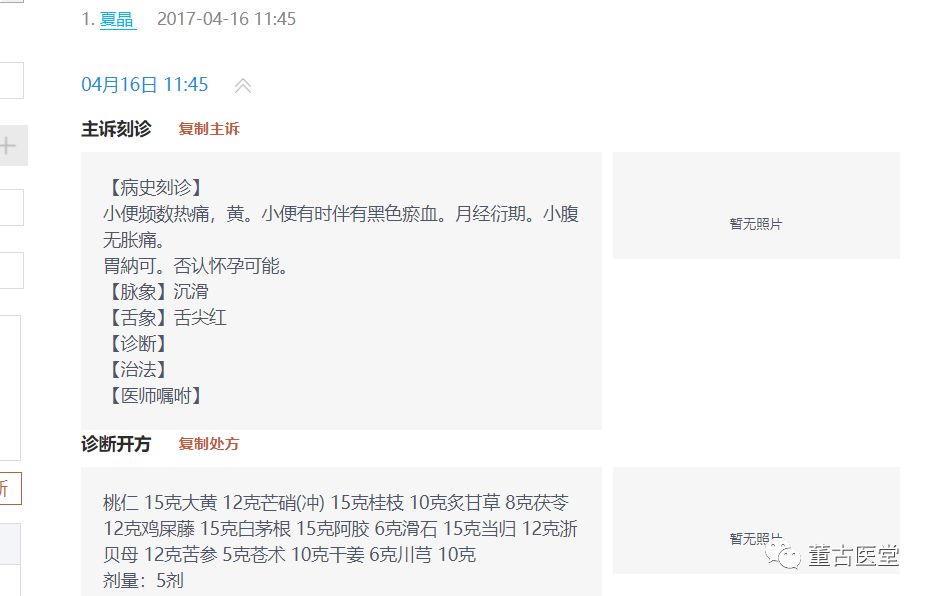

The patient came for treatment due to delayed menstruation, accompanied by frequent, hot, yellow urination with blood clots. The pulse was deep, slippery, and strong. As shown:

This symptom clearly indicates bladder damp-heat stagnation injuring the blood component, leading to bladder accumulation of water and blood. Coupled with a deep and slippery pulse, this is a case where the pulse and symptoms correspond. The treatment is clear. I chose 桃核承气汤 (Tao He Cheng Qi Tang) combined with 猪苓汤 (Zhu Ling Tang) with modifications. I also added 当归 (Dang Gui), 贝母 (Bei Mu), and 苦参 (Ku Shen) to the formula, which in hindsight seems unnecessary.

After taking the medicine, the patient’s menstruation quickly returned. All other symptoms also disappeared.

Of course, there are also cases of deep string pulse, indicating water-dampness in the interior, for which 苓桂术甘汤 (Ling Gui Zhu Gan Tang), 五苓散 (Wu Ling San), 真武汤 (Zhen Wu Tang), and 附子汤 (Fu Zi Tang) can be selected based on the situation.

For deep, soft pulses, 术附汤 (Shu Fu Tang) can be used as the main formula with modifications.

For deep, rough pulses, 抵挡汤 (Di Dang Tang) and 桃核承气汤 (Tao He Cheng Qi Tang) can be used with modifications.

For deep, thin, and strong pulses, 当归四逆汤 (Dang Gui Si Ni Tang) can be used with modifications.

For deep, thin, and tight pulses, 麻黄附子细辛汤 (Ma Huang Fu Zi Xi Xin Tang) can be used.

We welcome fellow practitioners to exchange and correct!

Dr. Dong (WeChat ID: 13310830760)