New Friends: Click the blue text below the title to quickly follow.

Old Friends: Click the share button in the upper right corner to share this exciting content.

More Information: Open the Therapeutic Encyclopedia public platform and click the upper right corner to view historical records.

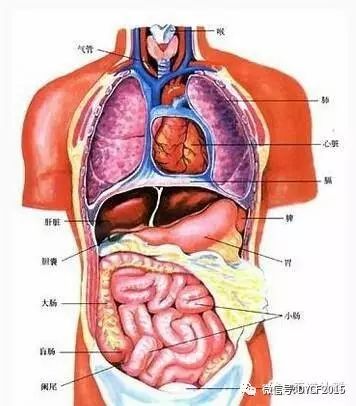

The Six Fu Organs

The term “Six Fu” refers to the six organs in the human body: the gallbladder (dǎn), stomach (wèi), large intestine (dà cháng), small intestine (xiǎo cháng), bladder (páng guāng), and San Jiao (三焦). The term “Fu” was historically known as “府” (fǔ), meaning a storage house. The primary physiological function of the Six Fu is to receive, digest food, separate the clear from the turbid, transform essences, and expel waste from the body without retention. Therefore, the Six Fu should function harmoniously and smoothly. The specific physiological functions of the Six Fu are as follows: Food enters the stomach, is digested, moves down to the small intestine for further digestion, separates the clear from the turbid, and absorbs the essence. The large intestine receives the food residue from the small intestine, absorbs excess water, and expels the remaining waste as feces. During the digestion and absorption of food, the gallbladder secretes bile into the small intestine to assist in digestion. The San Jiao not only serves as a conduit for transformation but also plays a crucial role in regulating Qi, facilitating the normal functioning of transformation. The Six Fu work closely together in their physiological functions to complete the digestion, absorption, transportation, and excretion of food. In pathological changes, they can influence each other; for example, if the stomach has excess heat, it can consume body fluids, leading to constipation and poor large intestine function. Conversely, if the large intestine’s function is impaired, it can affect the stomach’s ability to receive food, causing poor appetite and abdominal distension.

Gallbladder

The gallbladder (dǎn) is attached to the liver’s small lobe and is connected to the liver, appearing as a hollow sac-like organ. The gallbladder is one of the Six Fu organs and also one of the extraordinary organs. Its primary functions are: 1. To store and excrete bile, which is bitter and yellow-green, aiding in the digestion and absorption of food. Bile is transformed from the essence of the liver and stored in the gallbladder, hence it is referred to as the “repository of central essence” and “repository of purity.” The secretion of bile relies on the liver’s ability to regulate and control its flow. When the liver’s function is normal, bile flows smoothly, and the spleen and stomach’s transformation functions are robust. If liver Qi is stagnant, bile secretion is impaired, affecting the spleen and stomach’s digestive functions, leading to symptoms such as chest and rib fullness, poor appetite, or irregular bowel movements. If liver Qi is excessively dispersed, bile Qi may rebel upwards, resulting in bitter taste in the mouth and vomiting of yellow-green bitter fluid. If damp-heat accumulates in the liver and gallbladder, bile may overflow to the skin, causing jaundice. Prolonged bile obstruction can lead to the accumulation of stones. 2. To govern decision-making, which falls under the realm of cognition. The gallbladder’s role in decision-making is crucial for defending against and eliminating adverse effects of certain mental stimuli, maintaining and controlling the normal flow of Qi and blood, and ensuring coordination among the organs. Clinically, individuals with insufficient gallbladder Qi are often easily startled, fearful, and indecisive.

Stomach

The stomach (wèi) is located below the diaphragm, connecting above to the esophagus and below to the small intestine. The upper opening is called the cardia, and the lower opening is the pylorus. The stomach is divided into three parts: upper, middle, and lower, known as the upper, middle, and lower epigastrium, respectively. Thus, the stomach is also referred to as the “stomach cavity.” The primary functions of the stomach are: 1. To receive and digest food. The stomach receives and accommodates food from the esophagus and performs the initial digestion, transforming it into chyme. The stomach’s ability to receive and digest food provides the material basis for the spleen’s transformation function. Therefore, the spleen and stomach are often referred to as the “foundation of postnatal life, the source of Qi and blood production,” and their function is summarized as “stomach Qi.” The strength of the stomach Qi is closely related to the source of postnatal nutrition, and clinically, the strength of stomach Qi is an important basis for assessing the severity of diseases and prognosis, emphasizing the need to “preserve stomach Qi.” If the stomach’s receiving and digesting functions are abnormal, symptoms such as epigastric distension and pain, poor appetite, sour belching, and excessive hunger may occur. Severe damage to stomach Qi can lead to difficulty in eating, poor prognosis, and even life-threatening conditions, hence the saying, “If one has stomach Qi, one lives; without stomach Qi, one dies.” 2. To promote downward movement. This refers to the smooth downward flow of stomach Qi. After food is digested in the stomach, it is passed down to the small intestine for further digestion and absorption, with the clear being transported by the spleen and the turbid being passed to the large intestine for excretion. This entire process relies on the stomach Qi’s downward movement. Therefore, the stomach’s role in promoting downward movement is to ensure that chyme is passed down to the small and large intestines and that waste is expelled.

The stomach’s ability to promote downward movement is a prerequisite for the separation of turbid from clear. Thus, if the stomach fails to promote downward movement, it not only decreases appetite but can also cause upward turbid Qi, leading to bad breath, epigastric and abdominal distension and pain, belching, hiccups, constipation, and even nausea and vomiting.

Small Intestine

The small intestine (xiǎo cháng) is located in the abdomen, connecting above to the stomach through the pylorus and below to the large intestine through the ileocecal valve. It is a hollow tubular organ that is convoluted and coiled. Its primary functions are: 1. To receive and contain food. This means that the small intestine receives food that has been initially digested by the stomach and serves as a container. The food must remain in the small intestine for a period to allow for further digestion and absorption. The term “化物” (huà wù) refers to digestion and transformation, meaning that the small intestine further digests and absorbs the chyme, transforming the food into essence. If the small intestine’s functions of receiving and containing food are impaired, symptoms such as abdominal distension, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or loose stools may occur. 2. To separate the clear from the turbid. This function is expressed in two aspects: first, the small intestine receives food from the stomach, further digests it, and separates it into two parts: the clear essence and the food residue. The clear essence is transported by the spleen to the lungs to nourish the entire body, while the turbid residue is passed to the large intestine. Second, while the small intestine absorbs the clear essence, it also absorbs a large amount of fluid, which is transformed and enters the bladder, forming urine, hence the saying, “the small intestine governs fluids.” If the small intestine’s function of separating the clear from the turbid is impaired, it can lead to excessive fluid in the intestines, resulting in loose stools and reduced urination. Therefore, in clinical practice, the “separation method” is often used to treat diarrhea, known as “promoting urination to solidify the stool.”

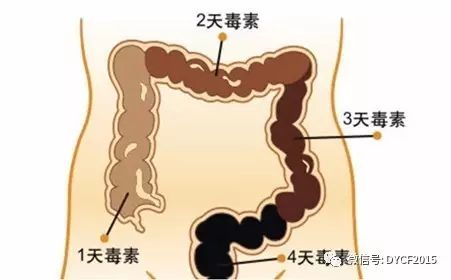

Large Intestine

The large intestine (dà cháng) is located in the abdominal cavity, connecting above to the small intestine through the ileocecal valve and below to the anus. It is a tubular organ that is coiled and folded. The primary function of the large intestine is to transmit and transform waste. “Transmission and transformation” refers to the conduction and change of food residue. The large intestine receives the food residue passed down from the small intestine, absorbs excess water, and forms feces, which are expelled through the anus, hence it is called the “transmission organ.” The large intestine’s transmission and transformation functions extend the stomach’s ability to separate turbid from clear and are closely related to the spleen’s ability to raise clear, the lungs’ ability to diffuse, and the kidneys’ ability to transform Qi. If the large intestine’s transmission function is impaired, it can lead to abnormal bowel movements, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea, tenesmus, or dysentery with pus and blood. If there is excess heat in the large intestine, the intestinal fluids may dry up, leading to constipation. If the large intestine is deficient and cold, it may lead to mixed food residues, intestinal sounds, and diarrhea.

Bladder

The bladder (páng guāng) is located in the lower abdomen and is a hollow sac-like organ. It connects above to the ureters and below to the urethra, opening at the front. The primary function of the bladder is to store and excrete urine. Urine is transformed from body fluids, and its formation relies on the kidneys’ Qi transformation, which is then transported to the bladder and regulates its opening and closing, ultimately being expelled from the body. Therefore, the bladder’s Qi transformation function is physiologically based on the kidneys’ Qi transformation. If the Qi transformation functions of the kidneys and bladder are impaired, it can lead to urinary difficulties, such as urinary retention, frequent urination, urgency, painful urination, or incontinence.

San Jiao

The San Jiao refers to the upper, middle, and lower Jiao, and is one of the Six Fu organs. Among the organs, the San Jiao is the largest, yet it is considered to have no physical form, hence it is called the “lonely organ.” Anatomically, the upper Jiao is above the diaphragm, including the heart and lungs; the middle Jiao is below the diaphragm and above the navel, including the spleen and stomach; and the lower Jiao is below the navel, including the liver and kidneys. The San Jiao is closely related to the pericardium. The specific functions of the San Jiao are: 1. To govern Qi, overseeing the body’s Qi transformation activities. The San Jiao is the pathway through which the body’s original Qi flows. The original Qi originates in the kidneys and must be distributed throughout the body via the San Jiao to stimulate and promote the functional activities of various organs, thus maintaining normal life activities. The original Qi is the driving force behind the body’s Qi transformation activities, and the San Jiao’s ability to facilitate the flow of original Qi is crucial for the normal functioning of Qi transformation throughout the body. Therefore, it is said that the San Jiao “governs Qi and oversees the body’s Qi transformation activities.” 2. To serve as the pathway for the movement of body fluids, indicating that the San Jiao has the function of clearing water pathways and facilitating the movement of body fluids. Although the metabolism of body fluids relies on the cooperation of various organs, it must also depend on the smooth functioning of the San Jiao’s water pathways. If the San Jiao’s water pathways are obstructed, the functions of the lungs, spleen, kidneys, and other organs that regulate body fluid metabolism cannot be effectively performed. Therefore, the San Jiao plays an important role in the metabolism of body fluids.

The gallbladder is the organ of decision-making; the stomach is the organ of storage; the large intestine is the organ of transmission; the San Jiao is the organ of drainage; and the bladder is the organ of storage for body fluids.