Four Diagnostic Methods in TCM: This refers to the “Four Diagnostic Methods” proposed by Bian Que based on the experiences of predecessors, namely: observation (望, wàng), listening and smelling (闻, wén), inquiry (问, wèn), and palpation (切, qiè). These four diagnostic methods are still widely used today and are important bases for TCM syndrome differentiation and treatment. The so-called “observation diagnosis” involves observing the patient’s spirit, color, shape, and state changes. “Spirit” refers to the mental and energetic state; “color” reflects the external manifestation of the vitality of the five organs; “shape” indicates the signs of the body being robust or weak; “state” reflects the dynamic performance of flexibility or rigidity. This involves observing the patient’s face, mouth, nose, teeth, tongue, and coating, as well as the limbs and skin to understand the patient’s “spirit”. Bian Que placed great importance on observation diagnosis, ranking it first among the four methods. The so-called “listening and smelling diagnosis” refers to listening to the patient’s voice, breathing, coughing, vomiting, belching, and the sounds of bowel movements, as well as smelling the patient’s body odor, bad breath, and the odors from phlegm, nasal discharge, and urine. The so-called “inquiry diagnosis” involves asking the patient about the onset and changes of the illness, cold and heat sensations, sweating, sensations in the head and body, bowel movements, diet, chest and abdomen, ears, mouth, and other conditions. Based on the summary of previous diagnostic methods, Bian Que also invented the “palpation method”. The “Records of the Grand Historian” states: “To this day, the world speaks of pulse diagnosis, it is due to Bian Que.” Sima Qian wrote a biography for famous doctors, placing Bian Que at the top, indicating Sima Qian’s respect for Bian Que and the importance of the palpation method. The so-called “palpation diagnosis” includes pulse diagnosis and touch diagnosis. Pulse diagnosis involves feeling the pulse to grasp the pulse pattern. Touch diagnosis involves using the hand to press on the patient’s body surface to observe the patient’s temperature, hardness or softness, and whether they resist or welcome pressure, which aids in diagnosis.

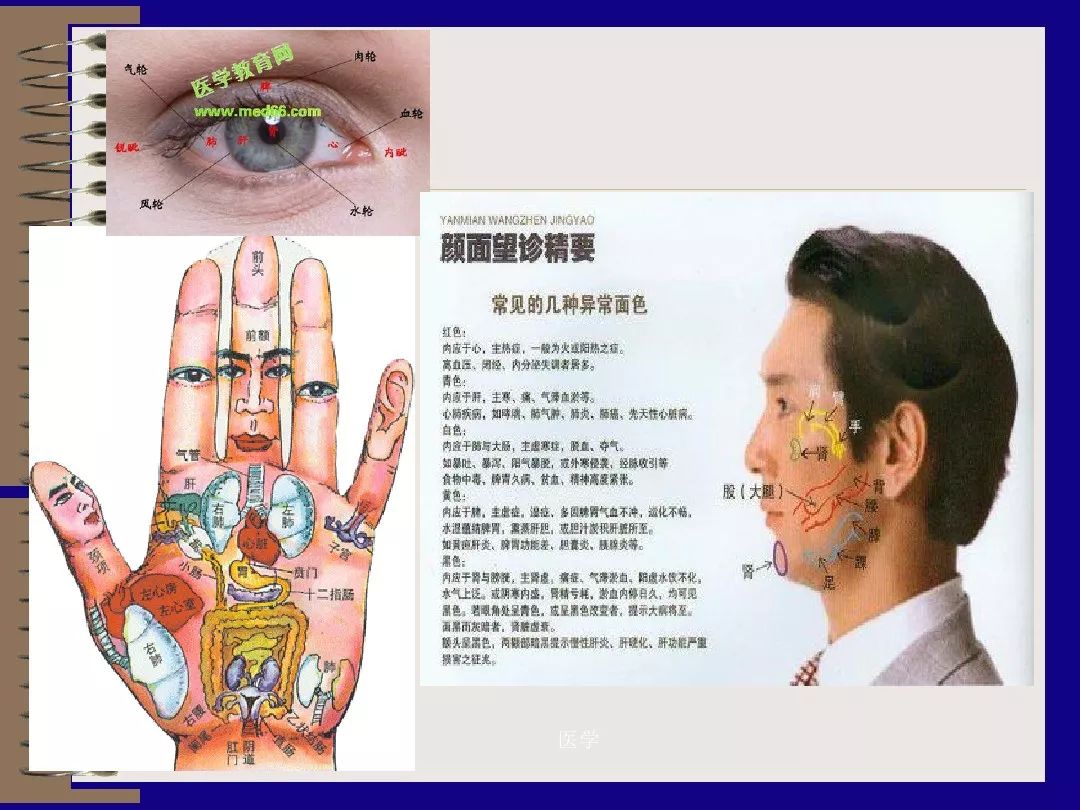

1. Observation Diagnosis In TCM, observation diagnosis mainly involves observing the patient’s overall or local spirit, color, shape, state, and excretions to diagnose the condition, especially the observation of the tongue, which plays a very important role.

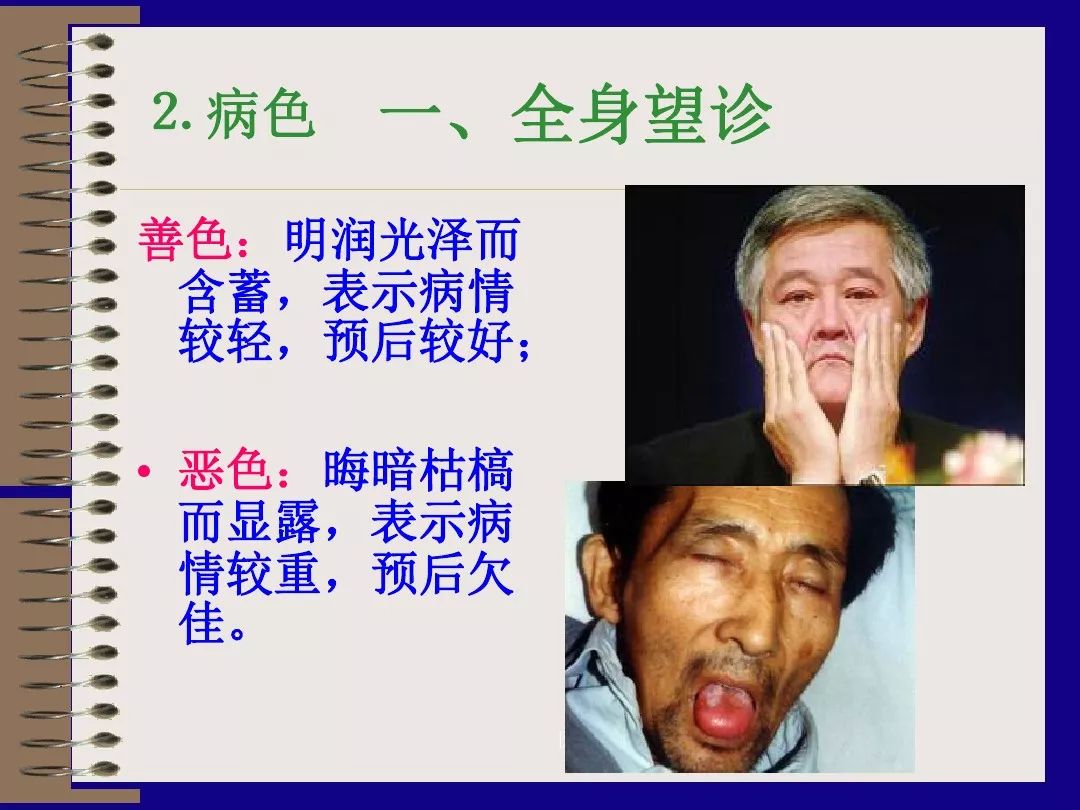

Observing the spirit: TCM believes that the spirit reflects the life activities of the body. A normal person possesses both form and spirit. It is expressed through the gaze, facial expressions, body movements, speech, and responsiveness. Observing the spirit requires distinguishing between having spirit, losing spirit, and false spirit.

1. Having spirit: The patient has a lively gaze, bright eyes, clear speech, lucid consciousness, even breathing, and moist skin, with normal control over bowel and bladder. This indicates that the patient’s organ functions are not declining, and even if there is illness, the prognosis is good.

2. Losing spirit: The patient has a dull gaze, lack of luster, fixed pupils, dark complexion, abnormal breathing, muscle wasting, slow response, or even loss of consciousness or sudden fainting. This indicates that the patient’s organ functions are failing, the condition is serious, and the prognosis is poor.

3. False spirit: The patient suddenly appears to be in good spirits, with flushed cheeks and bright eyes, but the eyeballs are fixed and unresponsive, and appetite increases. This is a sign that a critically ill patient is approaching death.

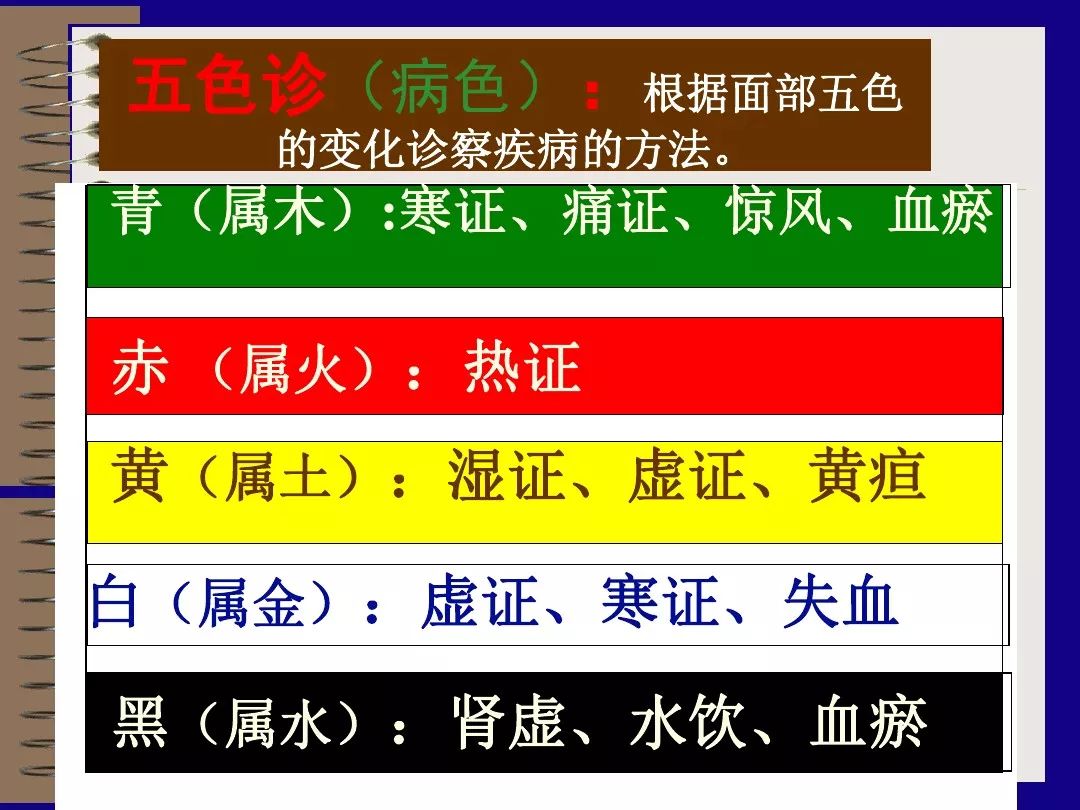

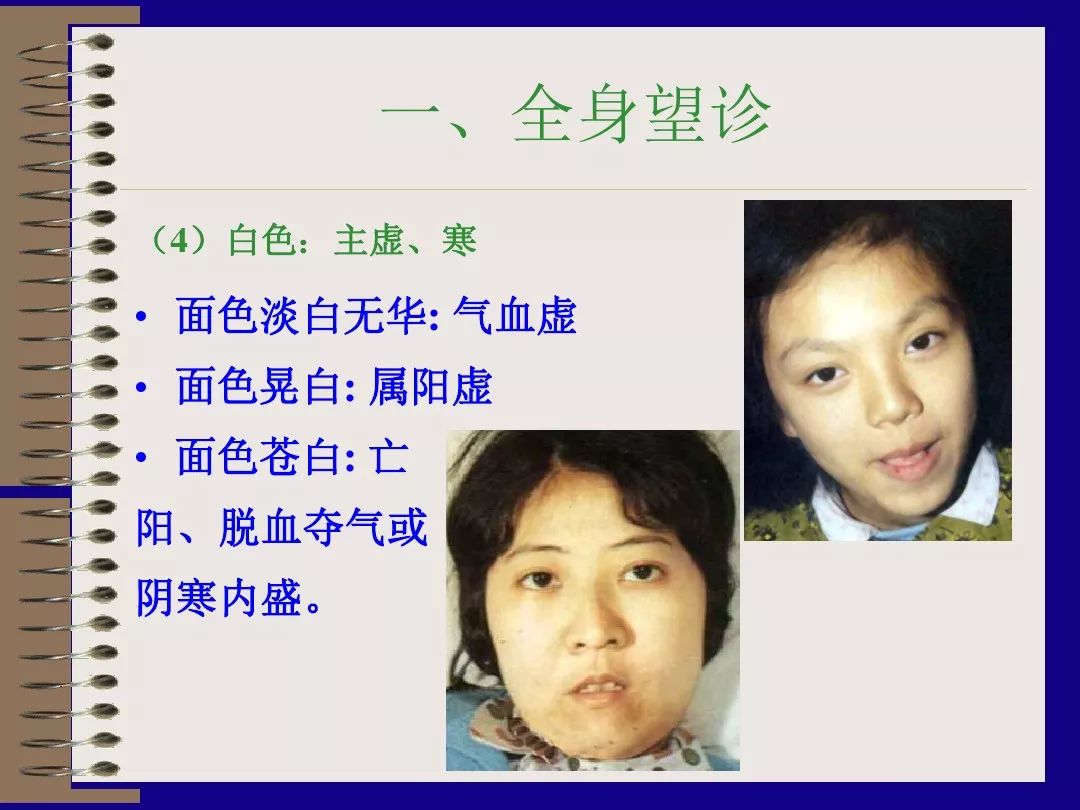

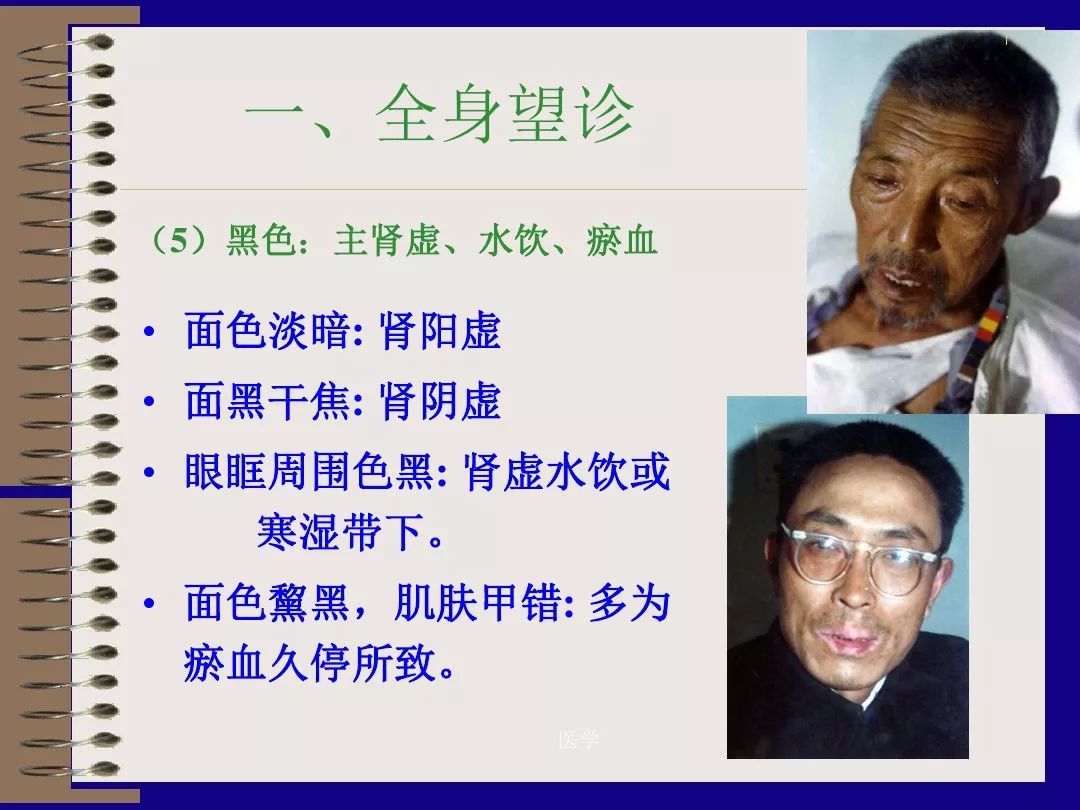

Observing complexion: A normal person’s complexion is rosy and lustrous, indicating abundant qi and blood and vigorous organ functions. The patient’s complexion may change abnormally due to illness, referred to as “disease color,” which is generally classified into five types: green (青, qīng), red (赤, chì), yellow (黄, huáng), white (白, bái), and black (黑, hēi).

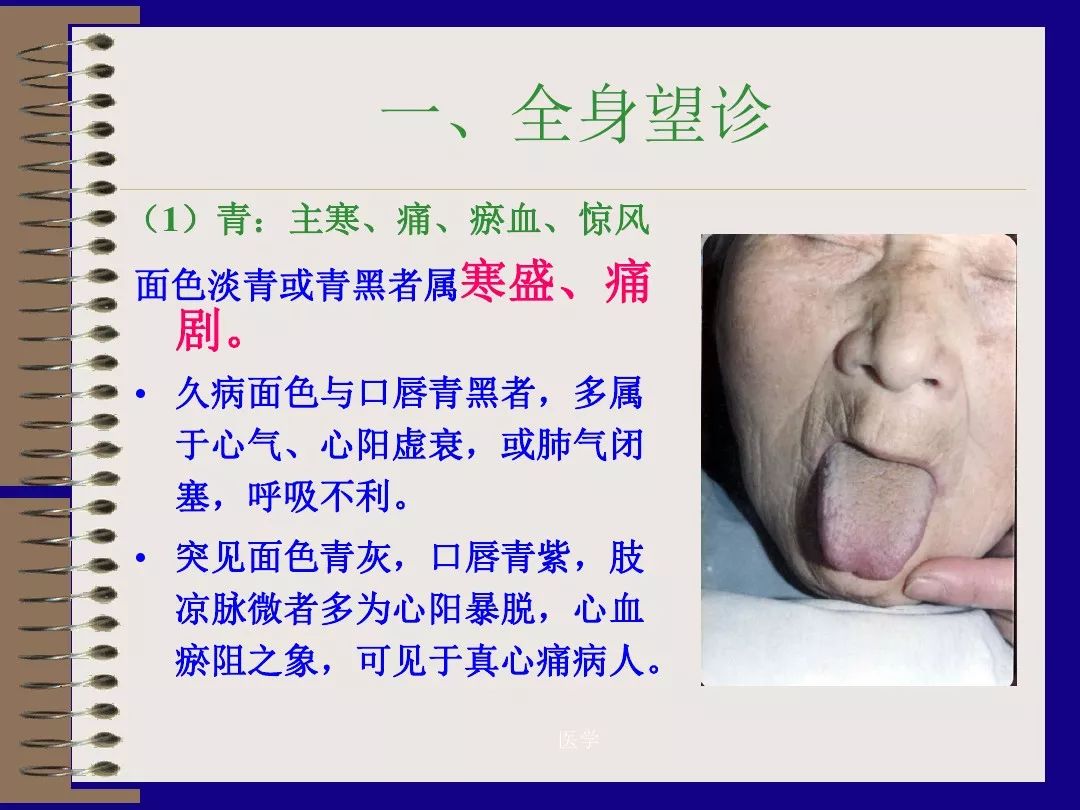

1. Green: Indicates cold syndrome, pain syndrome, blood stasis syndrome, pediatric convulsions, and liver disease. It indicates obstruction of the meridians and poor circulation of qi and blood.

2. Red: Indicates heat syndrome. It is a manifestation of blood filling the skin’s vessels. When the body is hot, blood circulation speeds up, resulting in a flushed face. A fully flushed face indicates true heat syndrome; in chronic diseases, a rosy complexion on the cheeks often indicates low fever, and if the patient feels hot, it indicates false heat syndrome. In patients with prolonged illness, a pale complexion that alternates between red and pale indicates a critical condition of true cold and false heat.

3. Yellow: Indicates damp syndrome and deficiency syndrome. A pale yellow complexion without luster is caused by spleen and stomach qi deficiency, leading to insufficient qi and blood. A complexion that is yellow like orange peel and yellowing of the whites of the eyes indicates damp syndrome. A yellow and emaciated complexion is often seen in patients with stomach disease and false heat; a yellow and pale complexion indicates stomach disease and false cold.

4. White: Indicates deficiency cold syndrome and blood deficiency syndrome. A white complexion with swelling indicates deficiency cold syndrome. A pale complexion indicates blood deficiency. A sudden pale complexion, excessive sweating, and cold extremities indicate a critical condition of yang qi collapse or excessive blood loss. White spots or patches on the face are often seen in patients with intestinal parasites.

5. Black: Indicates kidney deficiency syndrome, cold syndrome, pain syndrome, blood stasis syndrome, and water retention syndrome. Cold syndrome, pain syndrome, and blood stasis syndrome are due to kidney yang deficiency, leading to water retention and poor blood circulation, resulting in a black complexion. Dark circles around the eyes indicate phlegm retention syndrome.

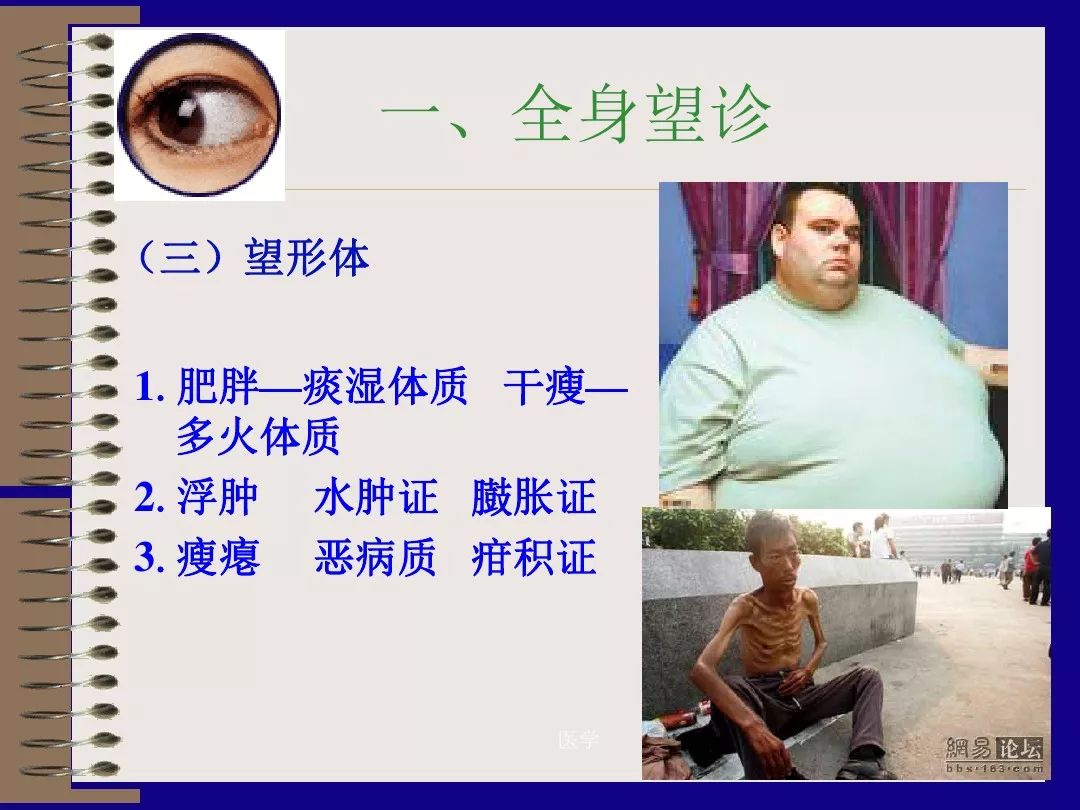

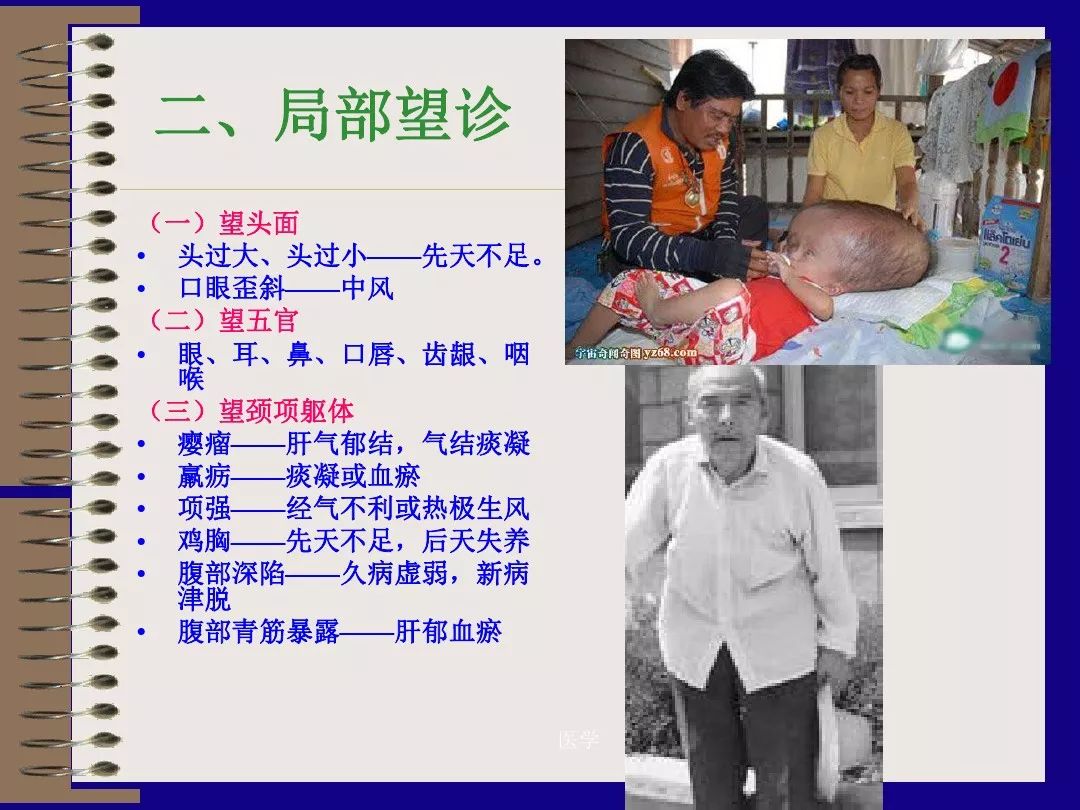

Observing shape and state: Shape refers to the body, and state refers to posture. By observing the patient’s body strength, fatness, and thinness, one can infer the internal organs, qi and blood, and the balance of yin and yang, the severity of the disease, and the prognosis.

1. Observing body shape: 1) Strong: A strong body, moist skin, firm muscles, robust physique, broad chest, and large bones indicate abundant qi and blood, strong resistance to disease, and easy recovery from illness.

2) Weak: A weak body, dry skin, thin muscles, frail and weak physique, narrow chest, and small bones indicate insufficient qi and blood, low resistance to disease, and difficulty in recovery from illness.

3) Fat: Obesity is not synonymous with health. The characteristics of a fat body include a round head, short and thick neck, broad and flat shoulders, wide and short chest, large abdomen, and short stature, often leaning backward. If a fat person has a good appetite, it indicates excess; if they eat little, have loose muscles, and lack energy, it often indicates spleen and stomach deficiency. Fat people with excess body fat and qi deficiency have difficulty circulating fluids, leading to dampness, and if stagnation leads to phlegm, they are prone to stroke.

4) Thin: Thinness is characterized by a long head, thin neck, narrow shoulders, flat chest, sunken abdomen, tall stature, and often leaning forward. Thin individuals have less body mass and blood, and if yin is deficient, excessive heat can harm the lungs, leading to cough in thin individuals.

2. Observing posture: Observing the dynamic posture can help determine the disease, as different movements reflect different diseases.

1) Walking posture: Leaning forward while walking and holding the abdomen often indicates abdominal pain; holding the waist and bending over often indicates lumbar and leg issues; unsteady walking indicates damage to the muscles and bones; suddenly stopping while walking and holding the heart indicates heart pain.

2) Sitting posture: Sitting with the head tilted back indicates phlegm accumulation in the lungs; sitting with the head bowed, shortness of breath, and reluctance to speak often indicates lung deficiency or kidney qi deficiency; often holding the head with the hands indicates headache.

3) Lying posture: Difficulty turning over while lying down and preferring to add clothing indicates deficiency syndrome or cold syndrome. Restlessness while sitting or lying down often indicates abdominal fullness and pain.

4) Standing posture: Unsteady standing often indicates dizziness, with qi and blood rising to the head. Inability to stand for long indicates deficiency of qi and blood. Standing with hands on the heart or abdomen often indicates heart or abdominal pain.

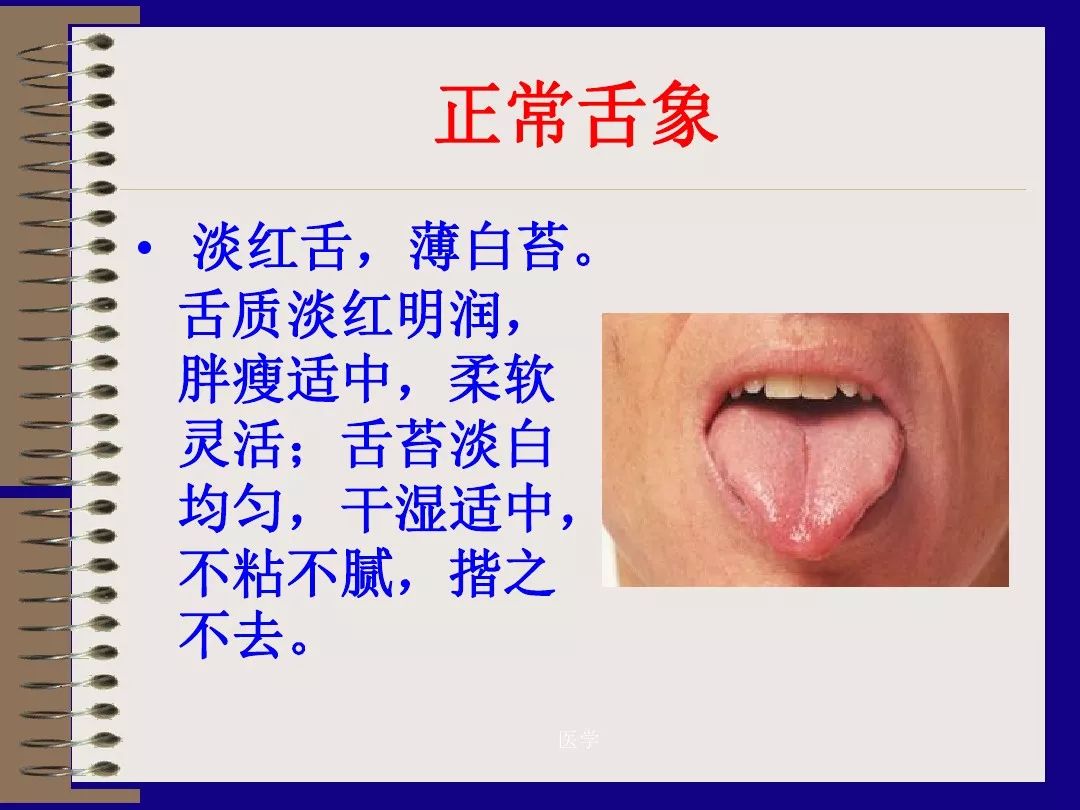

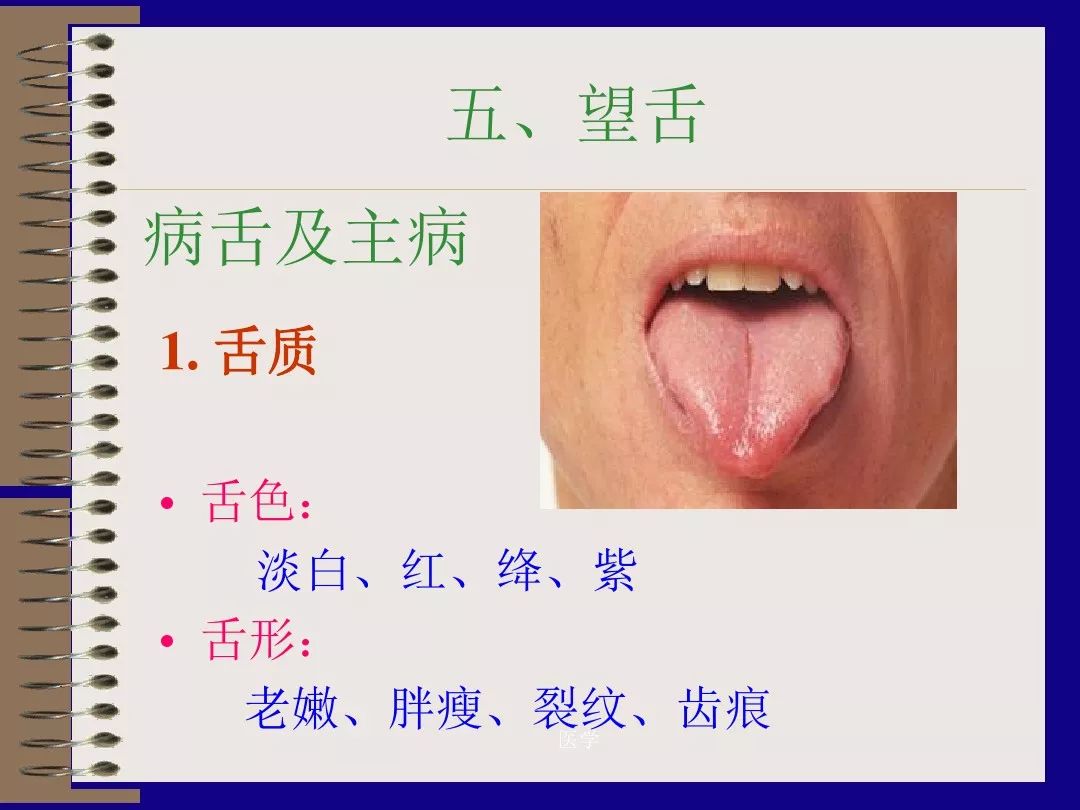

Observing the tongue: Tongue observation is a unique diagnostic method that involves examining the tongue’s quality and state, including its shape, color, moisture, and dryness, to assess changes in the disease. It holds an important position in TCM diagnosis. A normal tongue is pale red with a thin white coating. The tongue body should be soft, flexible, and pale red in color.

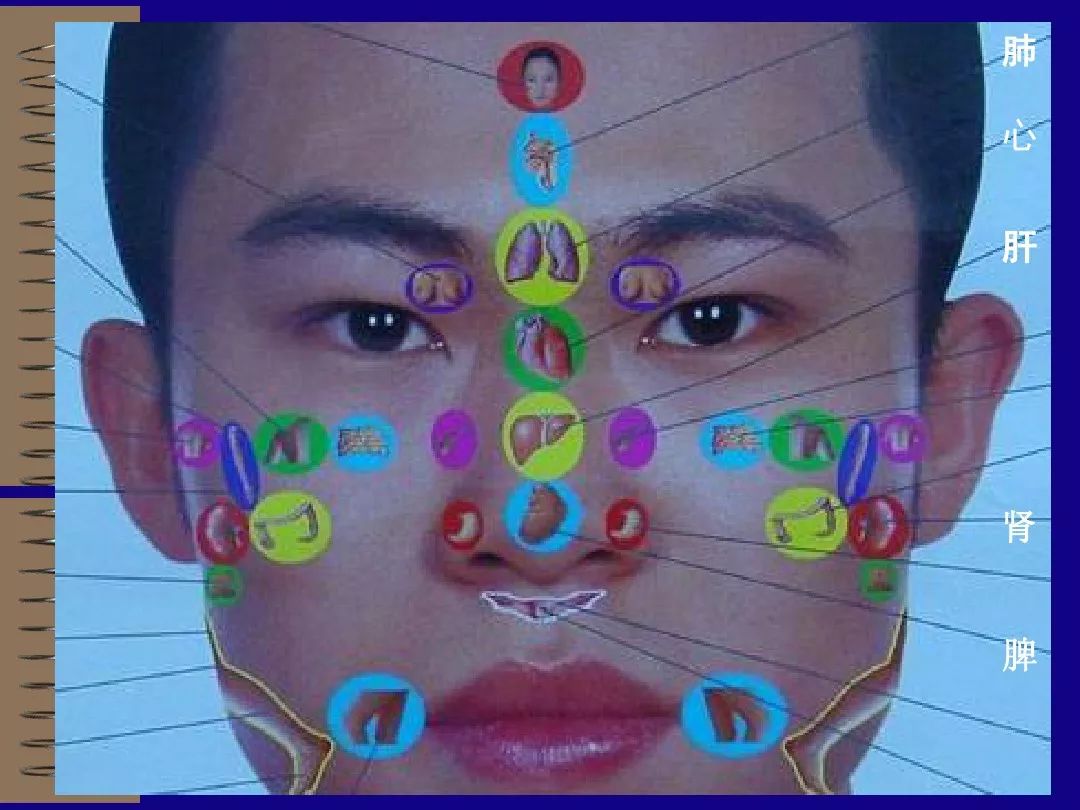

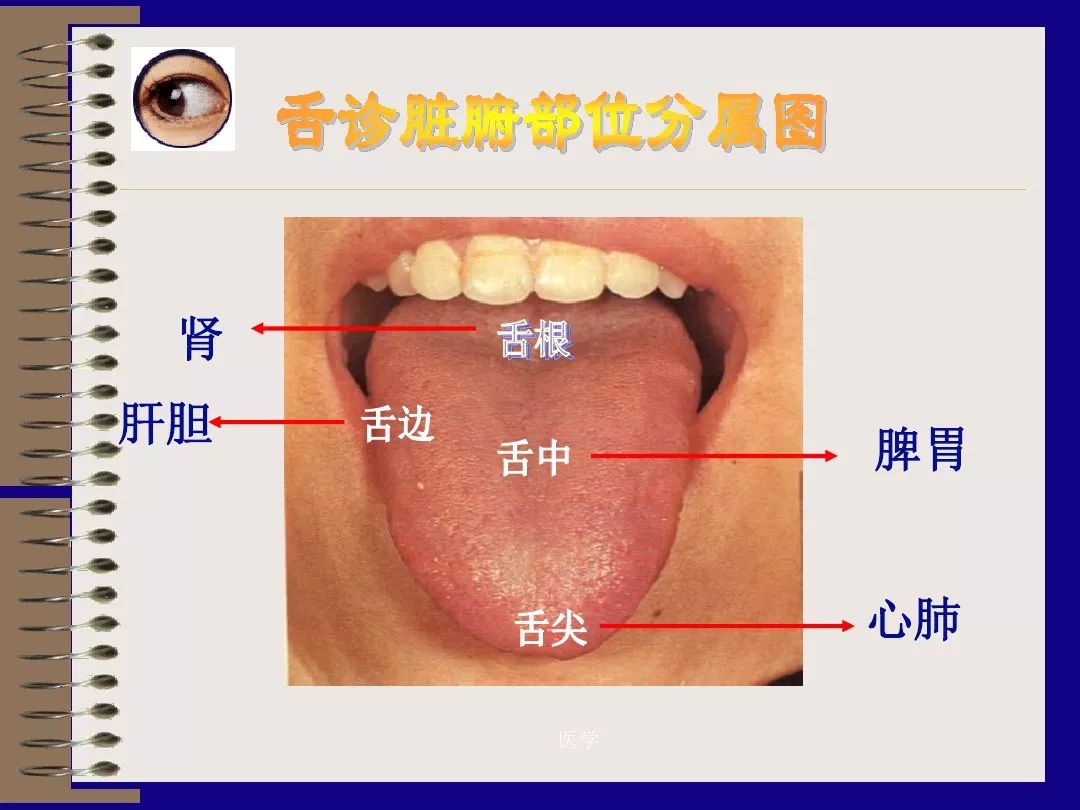

1) Observing tongue quality: The appearance of the tongue can indicate organ changes. Generally, the tongue tip reflects heart and lung issues, the sides reflect liver and gallbladder issues, and the root reflects kidney issues.

Tongue color: Mainly classified into pale red, pale white, red, and purple.

Pale red tongue: The tongue is pale red and moist with a hint of red. This indicates sufficient heart blood and vigorous yang qi, characteristic of a healthy person.

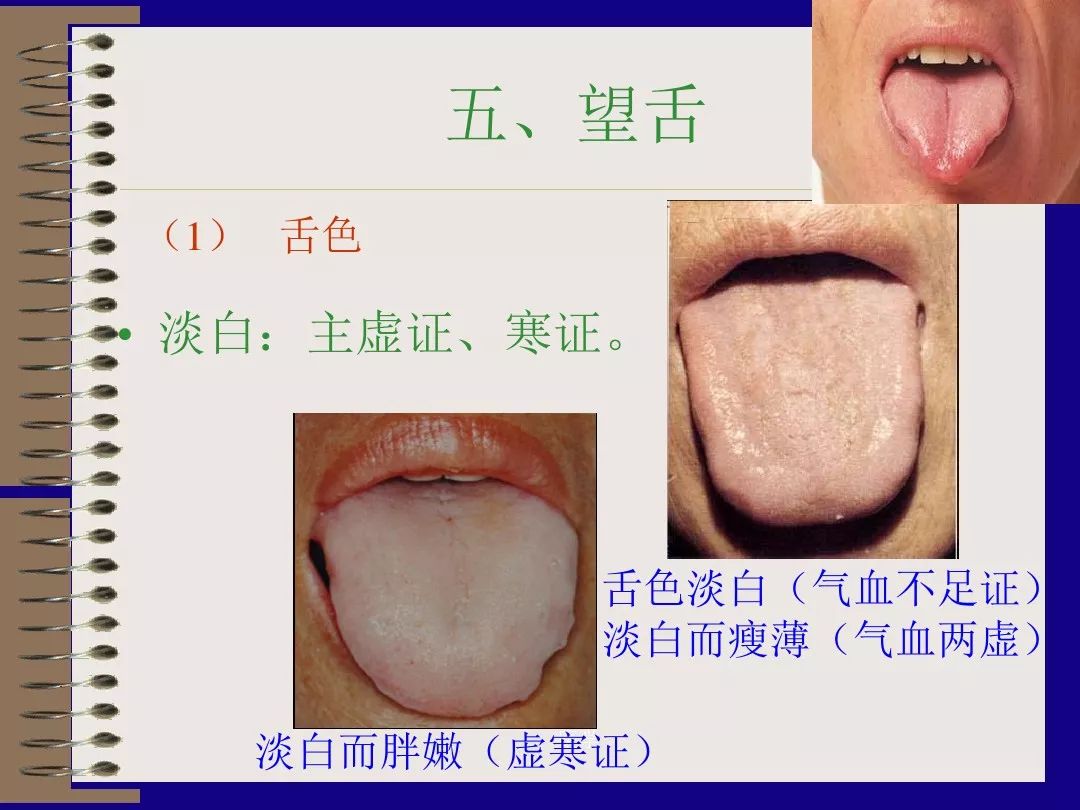

Pale white tongue: The tongue is lighter than a pale red tongue, with more white than red. This generally indicates qi and blood deficiency.

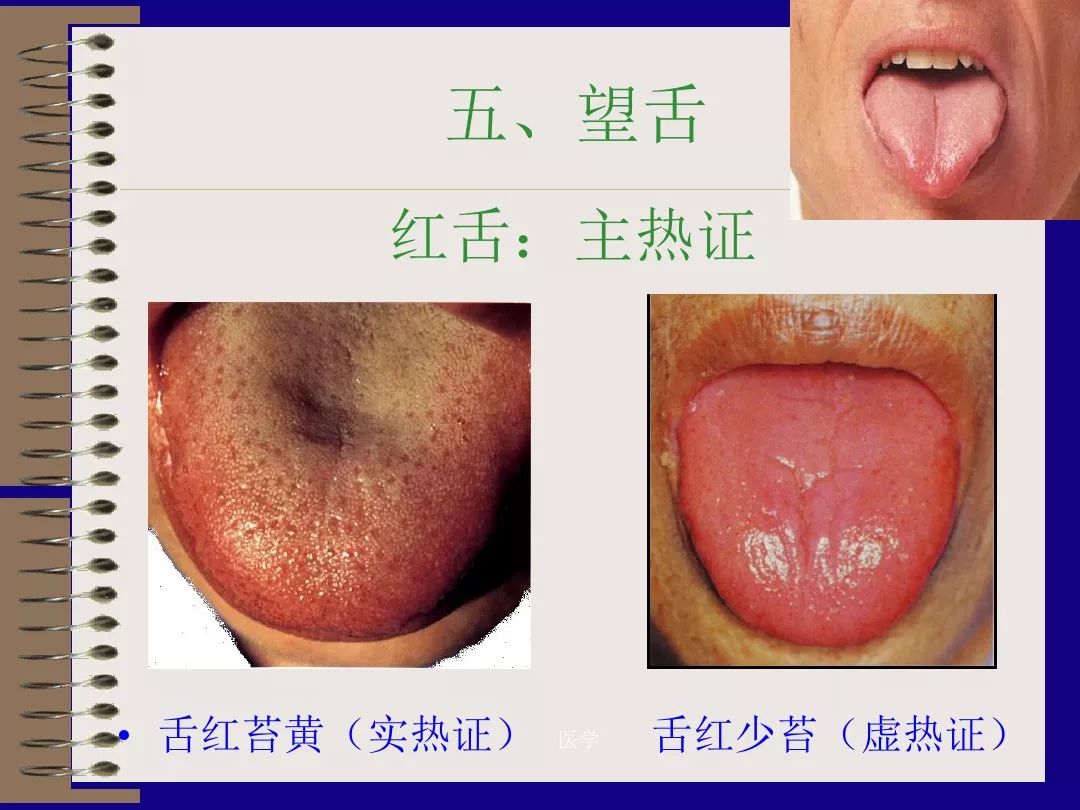

Red tongue: The tongue is redder than a pale red tongue. A bright red tongue is called a red tongue; a deep red tongue is called a scarlet tongue. This often indicates heat syndrome. A red tip indicates excessive heart fire; red sides indicate excessive liver and gallbladder fire; a red center indicates excessive stomach fire.

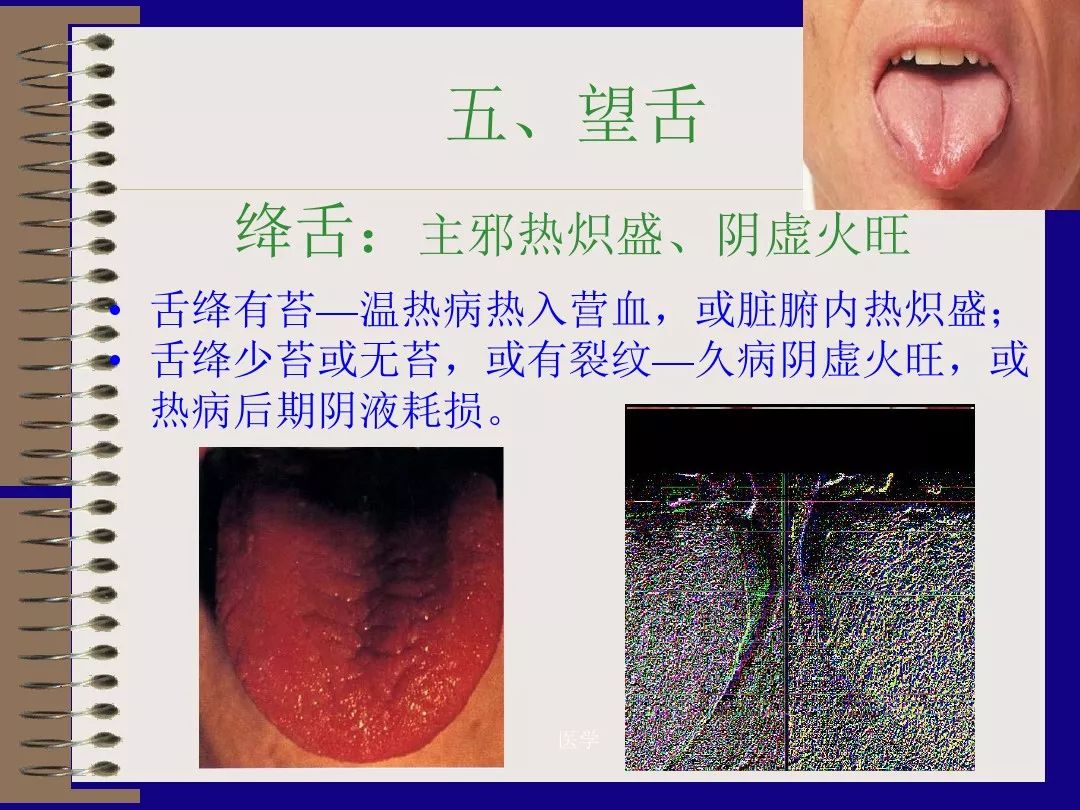

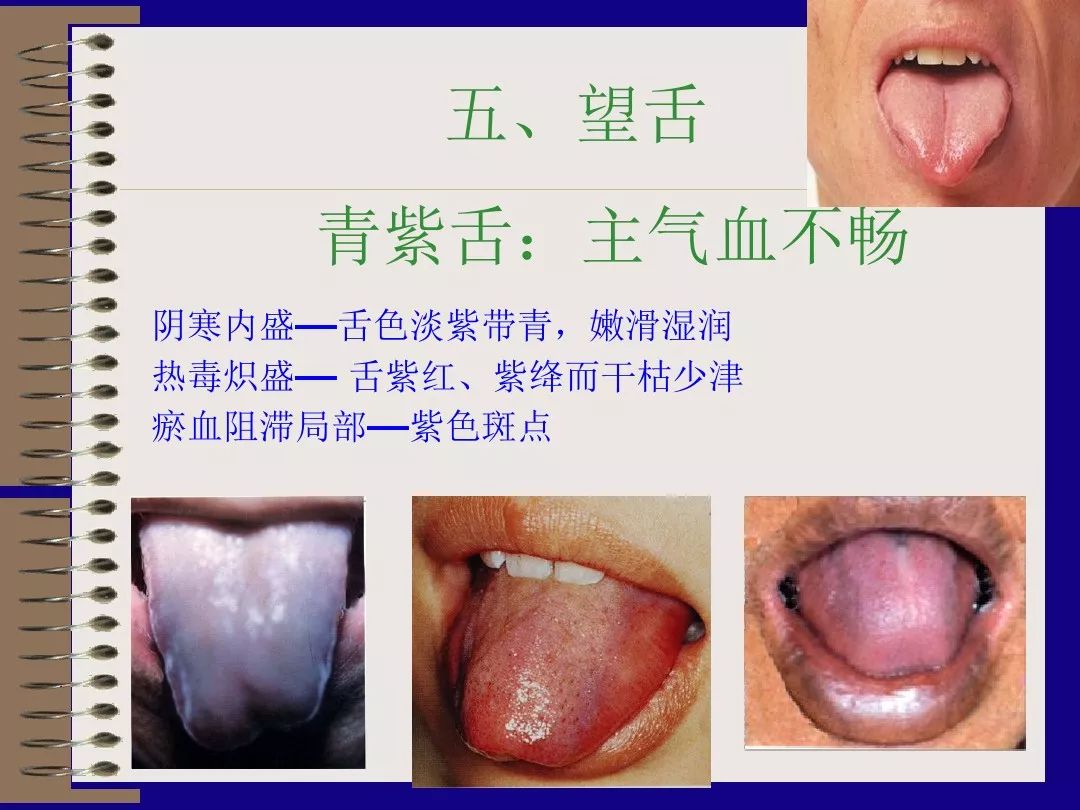

Purple tongue: The entire tongue appears uniformly blue or purple, or there are blue or purple spots or petechiae on the tongue. This indicates excessive heat toxin or internal cold, leading to poor circulation of qi and blood. This often indicates heat syndrome, cold syndrome, or blood stasis syndrome. A deep purple and dry tongue with little moisture indicates excessive heat toxin. A pale purple and moist tongue indicates internal cold. A dark purple or blue tongue indicates significant blood stasis; localized purple spots or petechiae indicate lighter blood stasis.

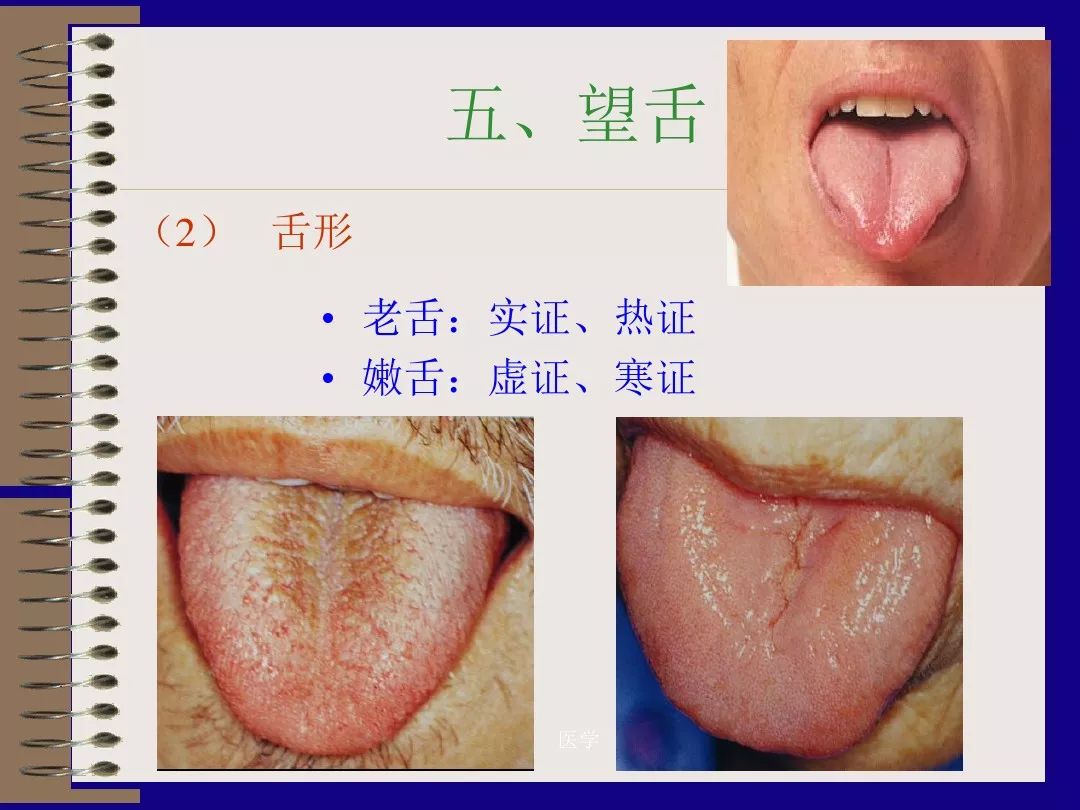

2) Observing tongue shape: Tongue shape refers to the size of the tongue. A normal tongue is of moderate size. Abnormal tongues include old tongue, tender tongue, enlarged tongue, thin tongue, cracked tongue, prickly tongue, and teeth-marked tongue.

Old tongue: The tongue has rough texture, indicating excessive heat and solid syndrome.

Tender tongue: The tongue has fine texture, often indicating poor circulation of qi and blood, with internal dampness, often indicating deficiency syndrome.

Enlarged tongue: The tongue is larger than normal, with relaxed muscles, indicating water retention and phlegm accumulation due to spleen and kidney yang deficiency.

Swollen tongue: The tongue is swollen, and the muscles appear enlarged, sometimes unable to close the mouth or retract, indicating excessive heart and spleen heat or alcohol toxicity. This often indicates solid syndrome. A bright red swollen tongue indicates excessive heart and spleen heat; a blue or purple swollen tongue indicates alcohol toxicity affecting the heart.

Thin tongue: The tongue is smaller and thinner than normal, indicating yin and blood deficiency, spleen deficiency, and atrophy of the tongue muscles.

Cracked tongue: The tongue surface has obvious cracks, which can take various shapes. This is caused by deficiency of essence and blood, indicating blood deficiency syndrome (except for congenital cracked tongues).

Prickly tongue: The tongue has red granules protruding like thorns, which feel prickly to the touch, indicating excessive heat. Prickly sides indicate excessive liver and gallbladder heat; prickly center indicates excessive stomach and intestinal heat.

Teeth-marked tongue: The edges of the tongue have indentations, indicating a swollen tongue. This often indicates spleen yang deficiency and internal water retention.

3) Observing tongue state: A normal tongue is flexible and moves freely. Pathological tongue states include rigidity, tremors, and deviations, indicating severe illness.

Rigid tongue: A red and rigid tongue is often seen in stroke precursors, often due to external heat or internal phlegm obstructing the heart or liver wind disturbing the mind.

Trembling tongue: The tongue trembles continuously. A pale white trembling tongue indicates blood deficiency; a red or scarlet trembling tongue indicates extreme heat generating wind.

Deviated tongue: The tongue is not straight and deviates to one side when extended. This often indicates stroke or stroke precursors.

Shortened tongue: The tongue is tight and cannot extend, sometimes unable to touch the teeth (except for congenital short tongues). A red or scarlet shortened tongue indicates heat disease, often seen in comatose patients.

Protruding tongue: The tongue repeatedly extends outside the mouth, with prolonged extension and slow retraction indicating protruding tongue; immediate retraction indicates moving tongue. This often indicates poor intellectual development in children.

4) Observing tongue coating: This mainly involves observing the thickness, moisture, dryness, decay, and peeling of the tongue coating.

Thickness of coating: A thin coating allows the tongue body to be seen; a thick coating obscures the tongue body. A thin coating indicates the early stage of disease, while a thick coating indicates a more severe condition.

Moisture and dryness of coating: A moist and moderate coating is normal; a dry and rough coating indicates dryness. The degree of moisture and dryness indicates the balance of body fluids. If the tongue is red and the coating is moist, it indicates excessive heat; if the tongue is red and the coating is dry, it indicates dampness obstructing yang qi.

Decay coating: A loose coating with larger granules, thick on the sides and center, resembling tofu curds, indicates decay coating. A fine and dense coating indicates a more serious condition. Observing the decay coating can indicate the degree of yang qi and internal dampness. Decay coating often indicates food stagnation in the stomach or phlegm turbidity. A greasy coating indicates obstruction of yang qi, often seen in dampness or phlegm retention syndrome.

Peeling coating: If the tongue coating has partially peeled off, it indicates damage to the stomach qi or stomach yin. If the coating suddenly disappears, leaving a smooth surface like a mirror, it indicates a critical condition of damage to both stomach yin and qi.

5) Color of coating: The color of the coating can be classified into white, yellow, gray-black, etc.

White coating: Often indicates exterior syndrome or cold syndrome. A thin white and dry coating with a red tip indicates excessive heat in the lungs. A thick white coating indicates phlegm dampness.

Yellow coating: Often indicates heat syndrome, with the degree of yellow indicating the severity of heat. Gray-black coating: A light black coating is gray coating; a deep black coating is black coating. Gray-black coating often indicates severe internal heat, with the darker the color, the more severe the condition. If the coating is gray-black and moist, it indicates yang deficiency and cold, or phlegm dampness obstructing the body; if the coating is gray-black and dry, it indicates internal heat syndrome.

2. Listening and Smelling Diagnosis Listening and smelling diagnosis involves assessing the condition through sounds and odors. The content of listening can be divided into sounds, speech, breathing, vomiting, bowel sounds, and disease odors.

Normal sounds: The voice is natural, harmonious, and clearly expressed.

Abnormal sounds:

Hoarseness: Includes voice hoarseness and loss of voice. Hoarseness is difficulty in producing sound due to dryness of the throat; loss of voice is the complete inability to speak. This is often due to external wind-cold or wind-heat, or a combination of cold and heat injuring the lungs.

Snoring: If the patient is in a deep sleep and snoring continuously, it often indicates confusion of consciousness and obstruction of the airway. This is often seen in cases of heat entering the pericardium or stroke affecting the organs.

Moaning: When there is pain or fullness in the body, the patient may emit moaning sounds. This is often seen in headaches, chest pain, abdominal pain, or tooth pain.

Sneezing: Sneezing is caused by lung qi rising. This is often seen in cases of external wind-cold. If sneezing occurs after a prolonged illness, it may indicate recovery.

Speech: The heart governs the spirit; if there is a heart issue, speech may be disordered.

Slurred speech: Difficulty speaking fluently, unclear, slow, or not conveying meaning is often seen in post-stroke sequelae or late-stage heat illness.

Delirium: Confused consciousness and incoherent speech often indicate solid syndrome.

Weak voice: Confused consciousness, repetitive speech, and low volume often indicate deficiency syndrome.

Talking to oneself: Talking to oneself or mumbling is often seen in acute heat illness or in elderly patients with prolonged illness and heart blood deficiency.

Miscommunication: The patient speaks in reverse or disorderly, knowing they are wrong but unable to control it, often indicating insufficient heart qi.

Raving: Loud, rapid speech, often accompanied by shouting or raving, is often seen in phlegm-heat disturbing the heart.

Breathing: Breathing is related to the lungs and kidneys, and changes in breathing can indicate the condition of the organs.

Wheezing: Difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, or inability to lie flat indicates wheezing, which can be divided into deficiency and excess. Excess wheezing occurs suddenly, often in robust individuals with a strong pulse, indicating lung heat or phlegm retention. Deficiency wheezing develops slowly, with shallow breaths, often in weak individuals with a weak pulse, indicating lung and kidney deficiency.

Asthma: Rapid breathing accompanied by wheezing, with phlegm sounds in the throat, often indicates phlegm retention and external wind-cold. Prolonged exposure to cold and dampness or excessive consumption of sour, salty, or cold foods can also trigger asthma. Clinically, asthma and wheezing often occur simultaneously.

Shortness of breath: Shortness of breath with a dry throat and joint pain indicates excess syndrome; shortness of breath with weakness and difficulty urinating indicates deficiency syndrome.

Cough: Coughing is closely related to the lungs.

Heavy, turbid cough: Clear white phlegm and nasal congestion are often due to external wind-cold.

Cough with phlegm: Excessive phlegm that is easy to cough up is often due to cold cough, indicating phlegm dampness obstructing the lungs.

Cough with a barking sound: A barking cough accompanied by hoarseness is often seen in diphtheria.

Paroxysmal cough: Continuous coughing, sometimes with blood, is referred to as paroxysmal cough or whooping cough.

Vomiting: Vomiting is the expulsion of food, phlegm, or liquid from the stomach. Weak vomiting sounds and slow expulsion of clear phlegm indicate deficiency syndrome or cold syndrome.

Strong vomiting sounds with yellow, sticky phlegm or sour and bitter contents indicate excess syndrome.

Sour, rotten vomiting: Often due to overeating or excessive consumption of rich foods, leading to food stagnation in the stomach.

Bowel sounds: Bowel sounds can indicate the location and condition of the disease based on the sounds produced. Bowel sounds in the stomach resemble water in a bag, vibrating with sound, and pressing on it while walking indicates phlegm retention.

Bowel sounds in the abdomen: If the sounds decrease with warmth and food, but worsen with cold or hunger, it often indicates prolonged illness or excessive consumption of cold foods, leading to disharmony in the stomach and intestines.

Smelling disease odors:

Smelling disease odors can be divided into body odors and room odors.

Body odors:

Bad breath: Normal people do not emit foul odors when speaking. Bad breath indicates digestive issues, dental problems, or poor oral hygiene. Sour odors indicate food stagnation; putrid odors often indicate ulcerative sores.

Body odor: A foul body odor may indicate the presence of sores.

Room odors: A room with a bloody smell often indicates blood loss; foul-smelling urine indicates late-stage edema; a rotten apple smell indicates diabetes; all of these are signs of critical illness.

3. Inquiry Diagnosis Inquiry diagnosis involves systematically and purposefully questioning the patient or accompanying person. This includes the patient’s constitution, lifestyle habits, onset causes, course of illness and treatment, current symptoms, past medical history, and family history. Specifically, it can include questions about cold and heat sensations, sweating, pain, sleep, dietary preferences, and bowel movements.

Questions about cold and heat: The occurrence of cold and heat mainly depends on the nature of the pathogenic factor and the balance of yin and yang in the body, reflecting the interaction between the body’s righteousness and evil.

But cold without heat: The patient feels cold without fever, indicating a deficiency cold syndrome due to insufficient yang qi.

But heat without cold: The patient has a fever without feeling cold or even feels hot, indicating internal heat syndrome. If high fever is accompanied by thirst for cold drinks, sweating, and constipation, it indicates excess heat syndrome. If there is low fever in the afternoon, accompanied by hot palms and soles, night sweats, and flushed cheeks, it indicates internal deficiency heat syndrome.

Chills and fever: The patient feels cold and has a fever, indicating the initial stage of an external disease.

Alternating cold and heat: Cold and heat appear alternately. If the alternation is regular, it indicates malaria; if irregular, accompanied by pain in the sides and bitter mouth, it indicates liver and gallbladder disease.

Questions about sweating: Sweating is related to the balance of yang qi and the abundance of body fluids.

No sweating: If the patient has fever, chills, and headache without sweating, it indicates an excess exterior syndrome.

Excess sweating: If the patient has fever, chills, and sweating, it indicates a deficiency exterior syndrome.

Spontaneous sweating: Sweating with slight activity during the day, often accompanied by fatigue, shortness of breath, and cold intolerance, indicates damage to yang qi, often seen in internal injuries.

Night sweats: Sweating during sleep, accompanied by fever, flushed cheeks, irritability, insomnia, and dry mouth, indicates internal heat due to yin deficiency, often seen in internal injuries.

Questions about pain: Inquiring about the location, nature, and intensity of pain helps observe the condition.

Headache: Sudden, persistent headache, accompanied by chills and fever, often indicates an external excess syndrome. Intermittent headaches with a feeling of pressure that worsen with fatigue or dizziness often indicate internal deficiency syndrome.

Chest pain: Chest pain due to lung heat is often unilateral, accompanied by fever and cough with yellow, thick phlegm; chest obstruction syndrome presents as a feeling of pressure or stabbing pain in the heart area, often recurring with palpitations and shortness of breath; liver and gallbladder pain presents as discomfort in the sides; stomach pain presents as fullness and pain in the stomach area, often accompanied by belching and sour regurgitation.

Questions about sleep: Insomnia includes difficulty falling asleep, waking easily during the night, difficulty falling back asleep, or sleeplessness. This often indicates deficiency of yin and blood, leading to insufficient nourishment of the heart. It is often accompanied by palpitations, vivid dreams, tinnitus, and tidal fever. If phlegm-heat or food stagnation causes insomnia, it is often accompanied by a flushed face, shortness of breath, thirst, and discomfort in the stomach.

Excessive sleepiness: Excessive drowsiness and frequent involuntary sleepiness, often seen in elderly patients with weak bodies, indicates heart and kidney yang deficiency; in obese patients, it is often accompanied by abdominal distension and excessive phlegm, indicating spleen deficiency and excessive dampness, leading to failure of clear yang to rise.

Questions about dietary preferences: This includes understanding the amount of water intake, preference for hot or cold foods, appetite and food intake, and any abnormal tastes in the mouth.

Thirst and excessive drinking: Excessive thirst and drinking often indicate damage to body fluids, often seen in heat syndrome, dryness syndrome, or excessive sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea. If the patient prefers cold drinks, it indicates internal heat damaging body fluids. Frequent urination and weight loss indicate diabetes.

No thirst and not wanting to drink: Not feeling thirsty and not wanting to drink often indicates cold syndrome. If the patient feels thirsty but does not drink much, and prefers hot drinks, it often indicates damp syndrome or deficiency cold syndrome; if they prefer cold drinks, it indicates damp-heat syndrome.

Not wanting to eat and aversion to food: Not wanting to eat or finding food tasteless indicates a lack of appetite. If this occurs in a new illness, it often indicates food stagnation or external heat. If this occurs in a prolonged illness, it indicates spleen and stomach weakness. If there is aversion to certain foods, it often indicates food stagnation or liver and spleen damp-heat.

Excessive eating and picky eating: Excessive eating and feeling hungry often indicate excessive stomach fire; if a previously ill person suddenly eats excessively, it often indicates impending failure of spleen and stomach qi. Picky eating of raw rice, dirt, or foreign objects often indicates parasitic accumulation.

Taste: Bitter taste indicates liver and gallbladder heat; sour taste indicates food stagnation in the stomach and intestines; foul taste indicates excessive stomach fire; bland taste indicates dampness or deficiency; sweet taste indicates spleen damp-heat; salty taste indicates kidney deficiency.

Questions about bowel movements: Understanding the characteristics, color, odor, timing, quantity, and frequency of bowel movements, as well as the sensations during defecation and urination.

Abnormal bowel frequency: Difficulty defecating or not defecating for several days is called constipation. Heat accumulation damages body fluids, leading to heat constipation; internal cold leads to cold constipation; qi stagnation leads to qi constipation; qi deficiency leads to deficiency constipation. Loose stools or watery stools with increased frequency indicate diarrhea. Loose stools that are thin and unformed often indicate spleen failure to transport. Abdominal pain with diarrhea at dawn indicates five o’clock diarrhea, often due to kidney yang deficiency. Abdominal pain with diarrhea that improves after defecation often indicates food stagnation.

Abnormal stool quality: A burning sensation or feeling of heaviness in the anus during defecation indicates spleen deficiency and qi sinking. Incomplete defecation indicates liver qi stagnation. If there are undigested food particles in the stool, and pain decreases after defecation, it often indicates food stagnation. If the stool is yellow and sticky, it often indicates damp-heat accumulation in the large intestine. Abdominal pain with frequent urges to defecate often indicates damp-heat obstruction or intestinal qi stagnation, which are symptoms of dysentery. Incontinence often indicates kidney yang deficiency.

Abnormal urine volume: Increased urine volume often indicates deficiency cold. Decreased urine volume may be due to excessive heat, excessive sweating damaging body fluids, or vomiting and diarrhea damaging body fluids.

Abnormal urine frequency: Increased urination frequency, short, red, urgent urination indicates damp-heat. In prolonged illness, clear urine with increased frequency, or nighttime urination indicates kidney yang deficiency. Difficulty urinating, with dribbling, often indicates damp-heat or blood stasis, or obstruction by stones, indicating excess syndrome; if due to kidney yang deficiency, it indicates deficiency syndrome.

Abnormal sensations during urination: Painful urination, urgency, or burning sensations often indicate damp-heat descending to the bladder, commonly seen in gonorrhea. Incontinence during sleep indicates weak kidney qi. Confusion and incontinence indicate a critical condition.

4. Palpation Diagnosis Palpation diagnosis refers to the method where the doctor uses their fingers to press on the patient’s arterial pulse to explore the pulse pattern and understand the condition.

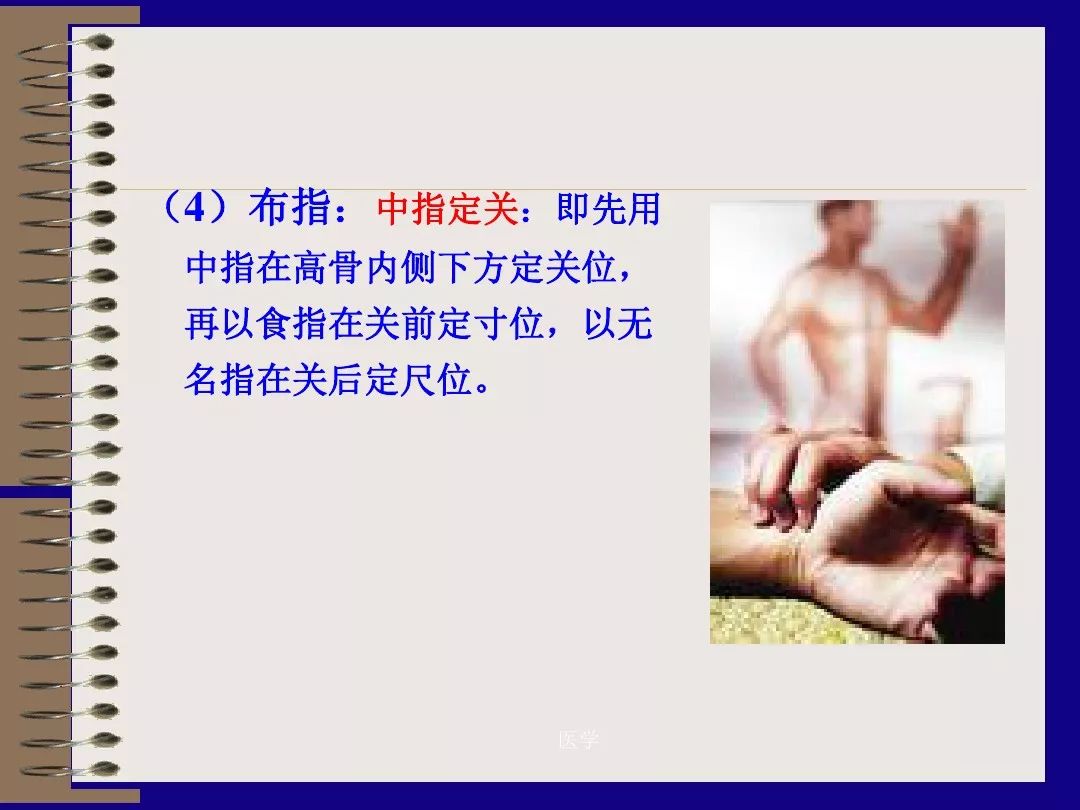

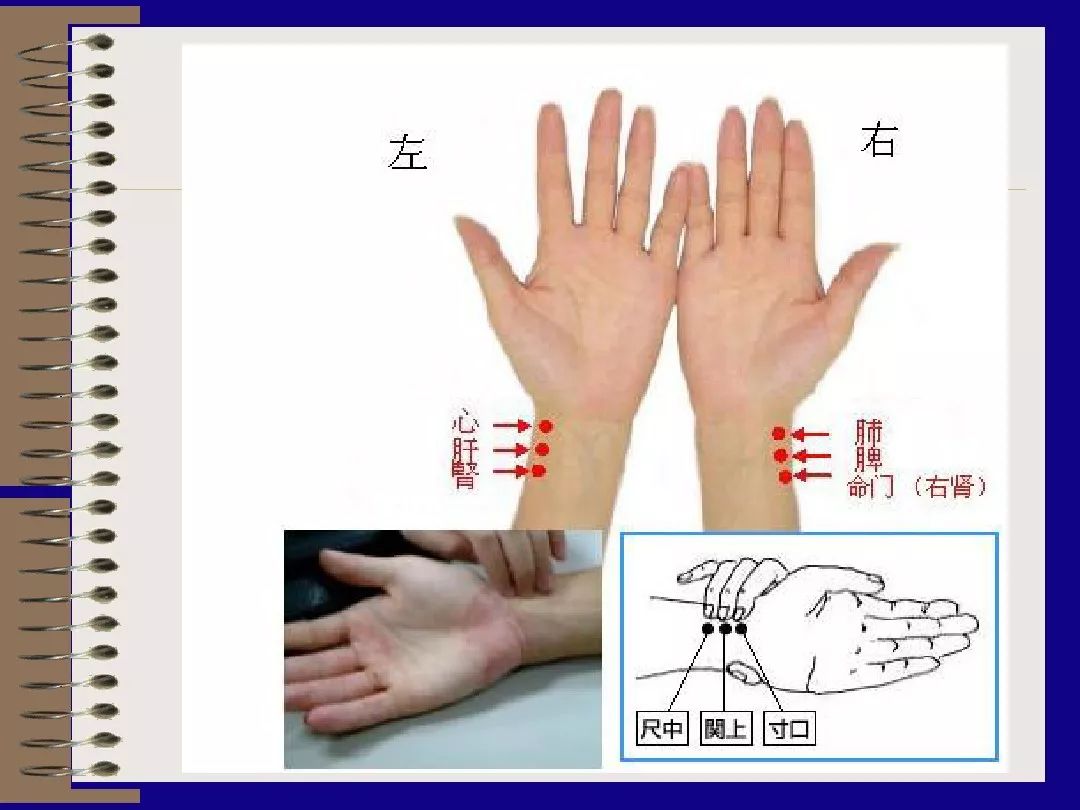

Palpation can be divided into three methods: comprehensive examination, three regions examination, and cun-kou examination, with the cun-kou method and abdominal examination being the most commonly used. The cun-kou is located at the radial artery pulse point behind both wrists, divided into cun, guan, and chi regions. The high bone at the back of the palm is the guan, the area in front of the guan is the cun, and the area behind the guan is the chi. The cun-kou pulse can reflect the qi of the organs: the left cun reflects the heart and small intestine; the left guan reflects the liver and gallbladder; the left chi reflects the kidney and bladder; the right cun reflects the lung; the right guan reflects the spleen and stomach; the right chi reflects the kidney.

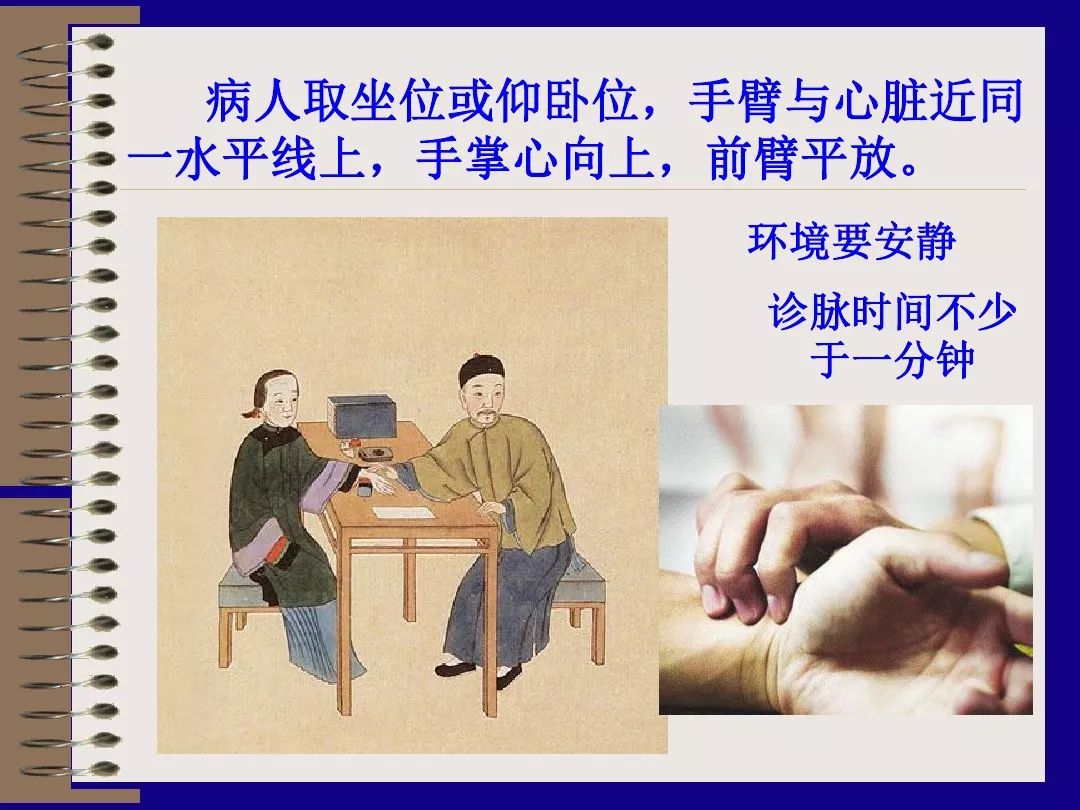

When palpating the pulse, attention should be paid to the time, posture, and technique. The examination should be conducted in the morning when the patient has not moved. If the patient has been active, they should rest for about 15 minutes before pulse diagnosis. The patient can be seated or lying down, with the arms extended and palms facing up, bringing the arms close to the heart level. During palpation, all three fingers should press the pulse simultaneously, with balanced pressure, ranging from light to heavy, divided into floating, moderate, and sinking pressure. The pulse diagnosis should last at least one minute.

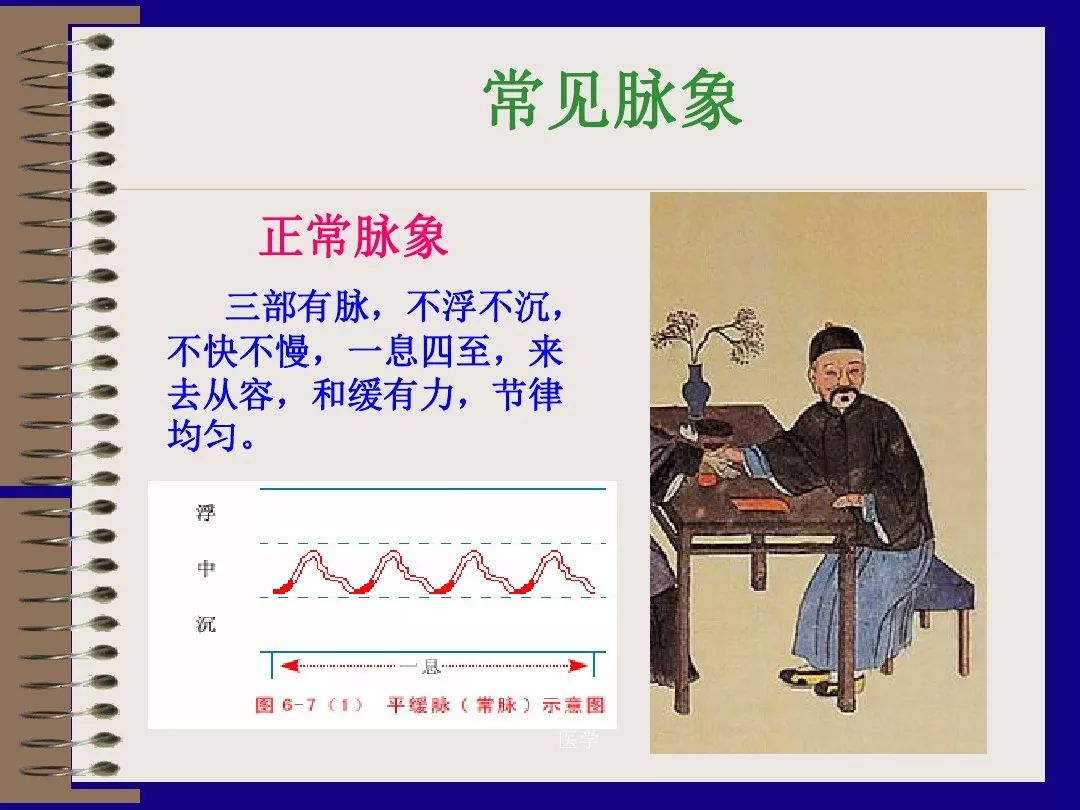

In healthy individuals, the pulse should beat four times with each breath, with pulses present in the cun, guan, and chi regions, not floating or sinking, and should be gentle and strong. The chi pulse should be strong when pressed. Common pulse patterns include floating pulse, sinking pulse, slow pulse, rapid pulse, weak pulse, strong pulse, slippery pulse, surging pulse, thin pulse, and wiry pulse.

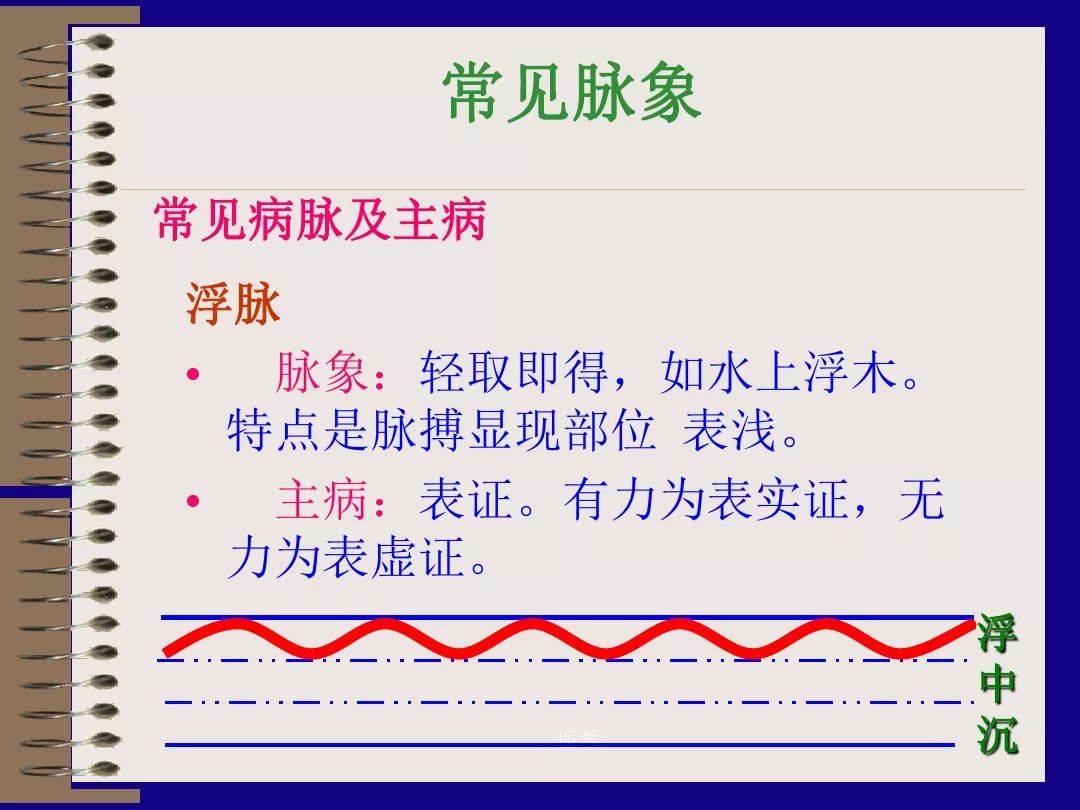

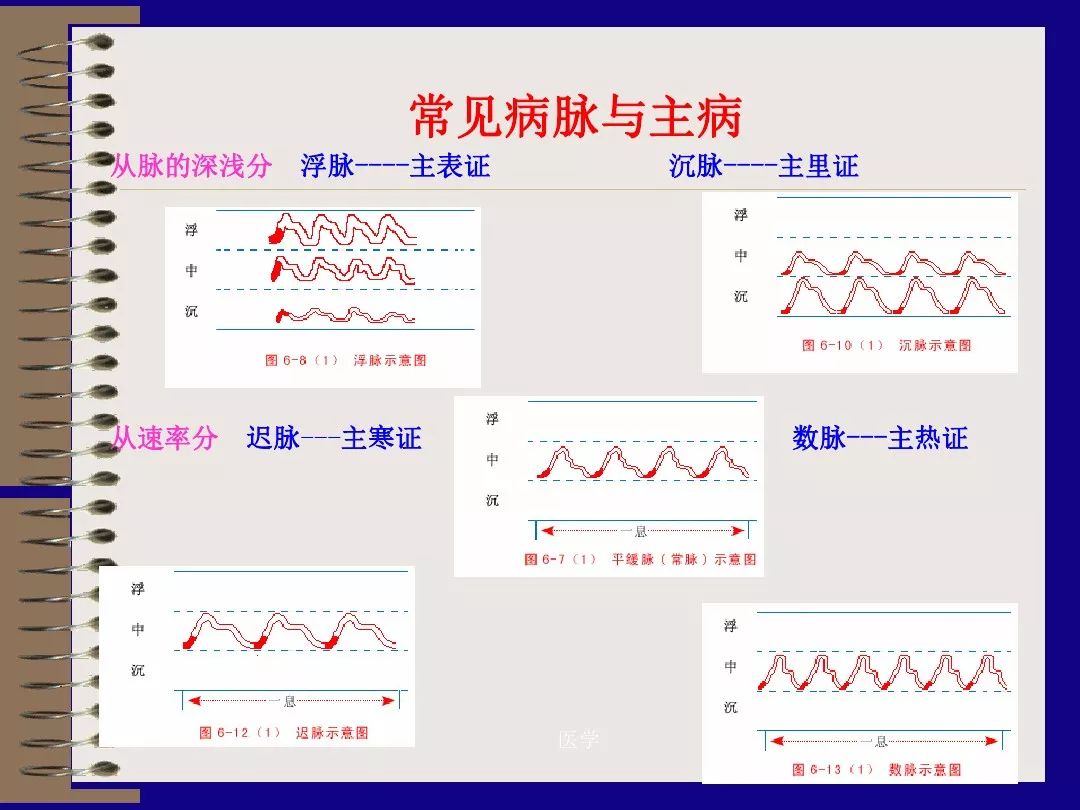

Floating pulse: Can be felt with light pressure but diminishes with heavy pressure. Indicates: exterior syndrome due to external pathogenic factors remaining on the surface, where the defensive qi resists the pathogen, causing the pulse to be superficial. A strong floating pulse indicates excess; a weak floating pulse indicates deficiency. In cases of internal injury and prolonged illness, due to deficiency of yin and blood, and insufficient yang qi, the pulse may be floating and weak, indicating a critical condition.

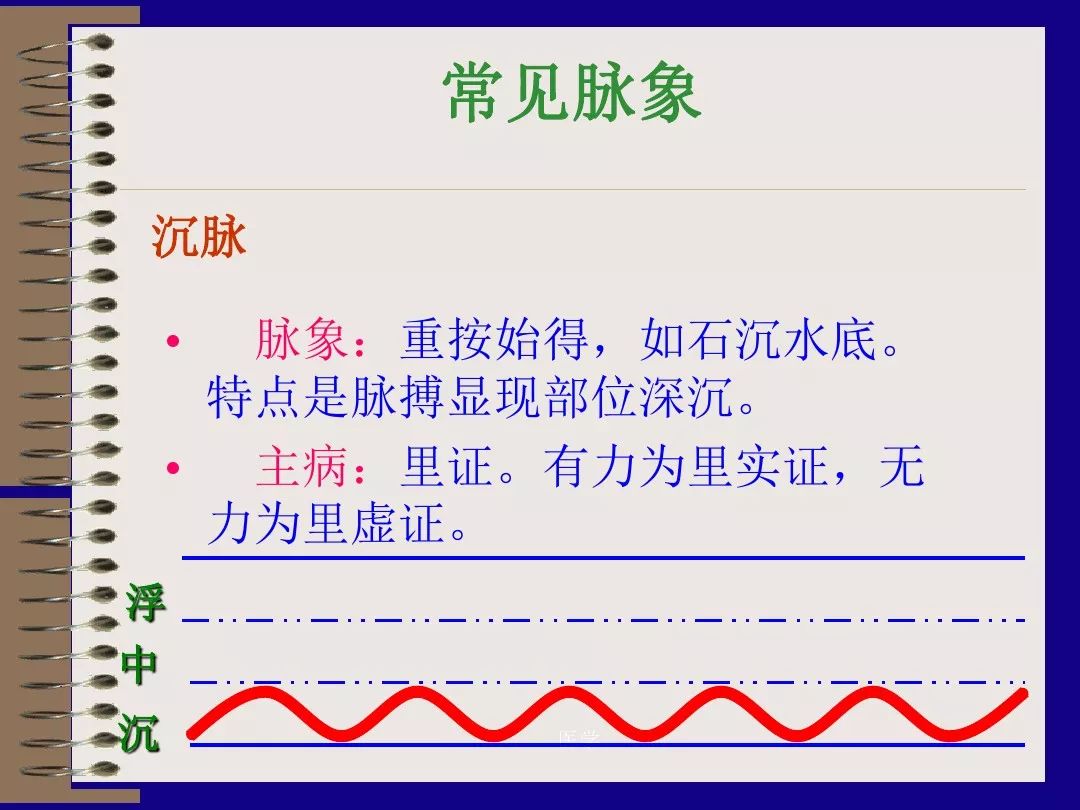

Sinking pulse: Cannot be felt with light pressure but can be felt with heavy pressure. Indicates: interior syndrome. A strong sinking pulse indicates excess; a weak sinking pulse indicates deficiency. If the pathogenic factor is trapped internally, qi and blood are obstructed, leading to poor circulation of yang qi, resulting in a strong sinking pulse; if the organs are weak, yang is deficient, and qi is trapped, the pulse will be weak.

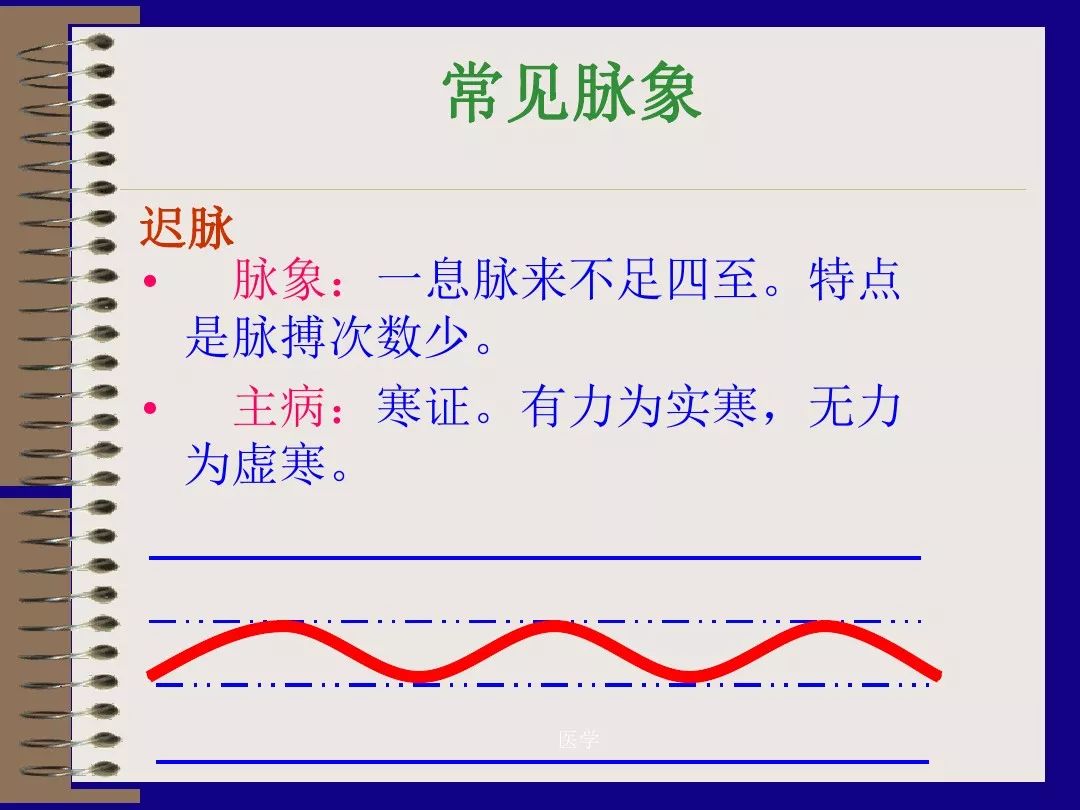

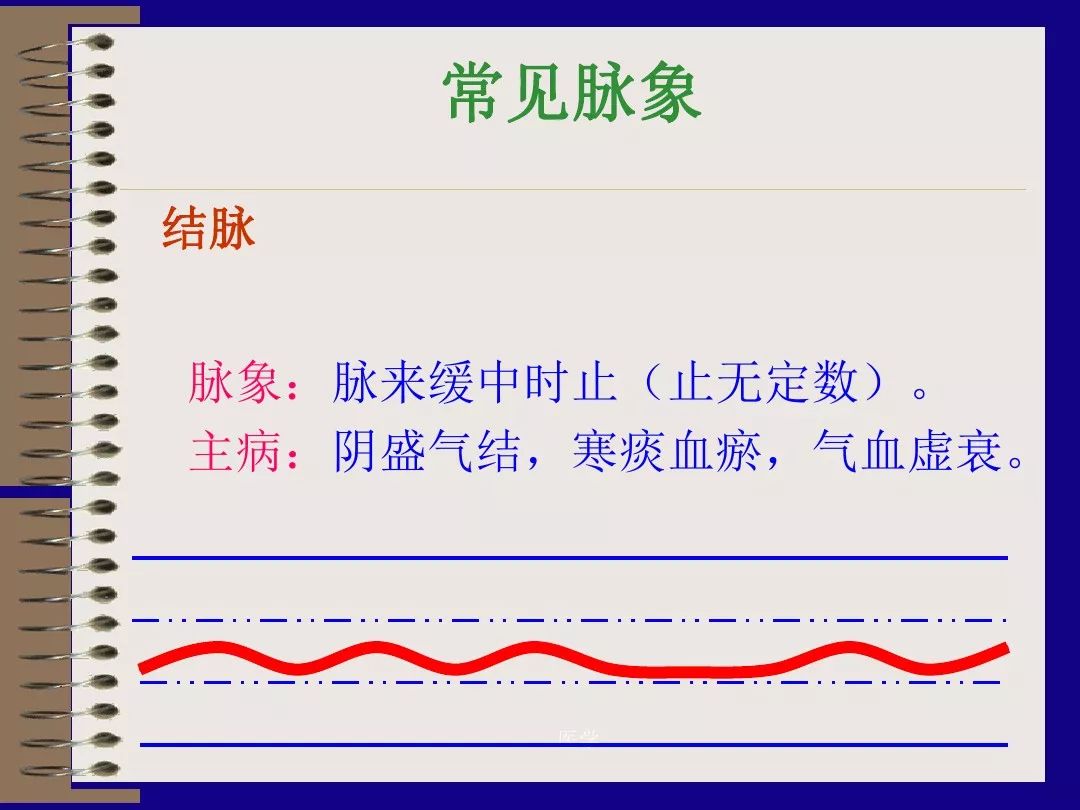

Slow pulse: A pulse rate of less than 60 beats per minute. Indicates: cold syndrome. A strong slow pulse indicates excess cold; a weak slow pulse indicates deficiency cold. Cold causes stagnation, slowing down the circulation of qi and blood, resulting in a strong slow pulse indicating excess cold syndrome. If yang qi is deficient, the pulse will be weak, indicating deficiency cold syndrome.

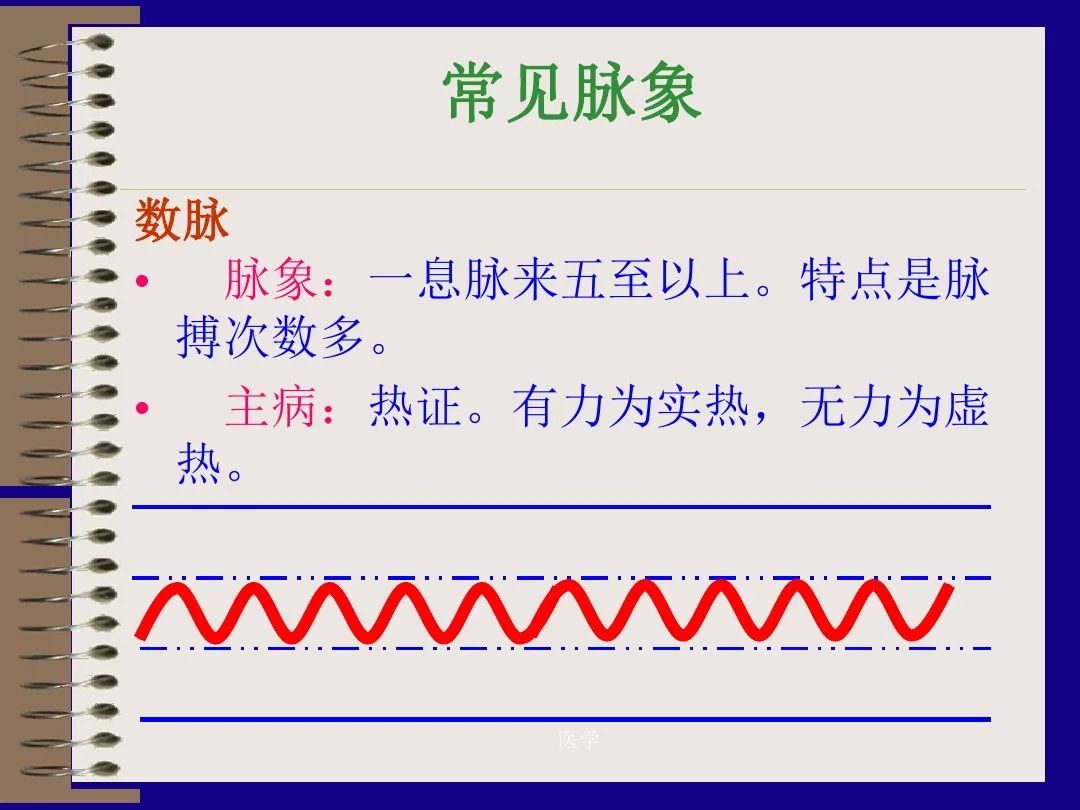

Rapid pulse: A pulse rate of more than 90 beats per minute. Indicates: heat syndrome. A strong rapid pulse indicates excess heat; a weak rapid pulse indicates deficiency heat. If an external heat illness occurs, or if the organs are hot, the pulse will be rapid and strong, indicating excess heat. If yin is deficient and fire is excessive, leading to insufficient fluids and blood, the pulse will be rapid and weak, indicating deficiency heat.

Weak pulse: All three regions of the pulse are weak. Pressing firmly feels empty. Indicates: deficiency syndrome, often due to deficiency of both qi and blood, where insufficient qi and blood cannot support the pulse, resulting in an empty feeling.

Strong pulse: All three regions of the pulse are strong. Indicates: excess syndrome, where the pathogenic factor is strong and the righteous qi is sufficient, leading to a vigorous pulse.

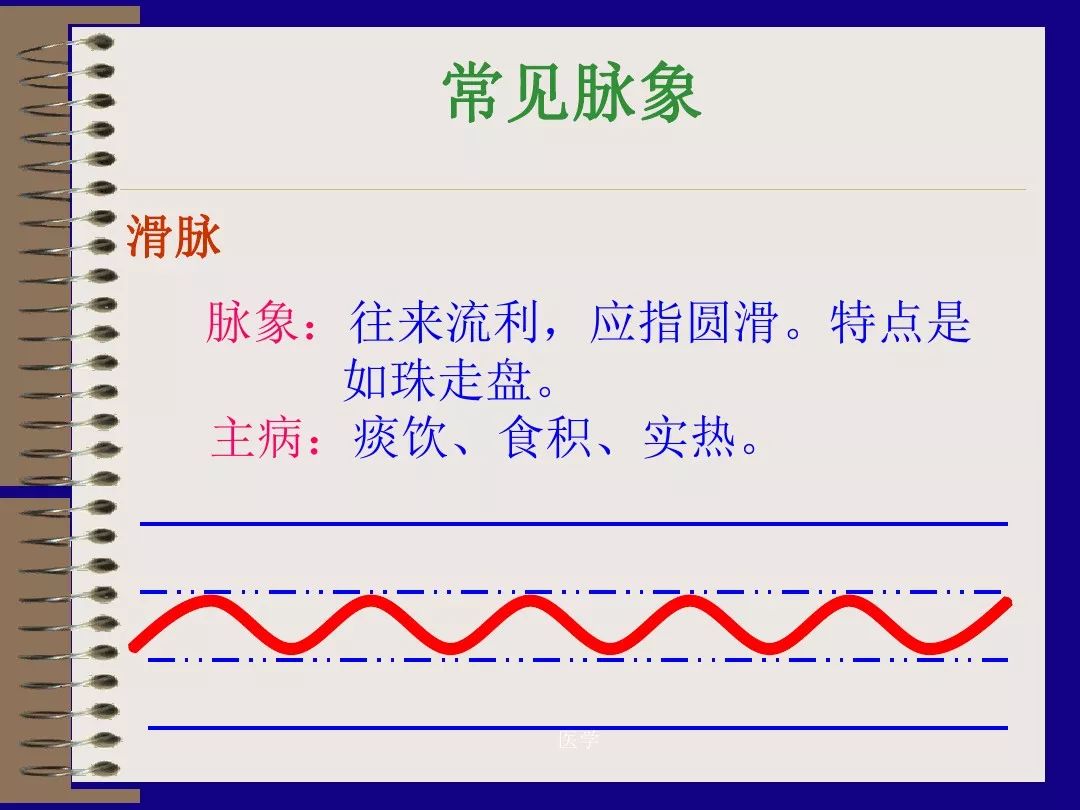

Slippery pulse: Feels smooth and flowing, like pressing a marble. Often seen in young and healthy individuals with abundant qi and blood. In pregnant women, a slippery pulse indicates strong qi and blood nourishing the fetus, which is a physiological phenomenon.

Surging pulse: A large and strong pulse, like waves surging, with a strong rise and fall. Indicates: excessive heat. When internal heat is excessive, the pulse vessels expand, and the pulse shape becomes wide, due to excessive heat burning, causing blood to surge, resulting in a surging pulse.

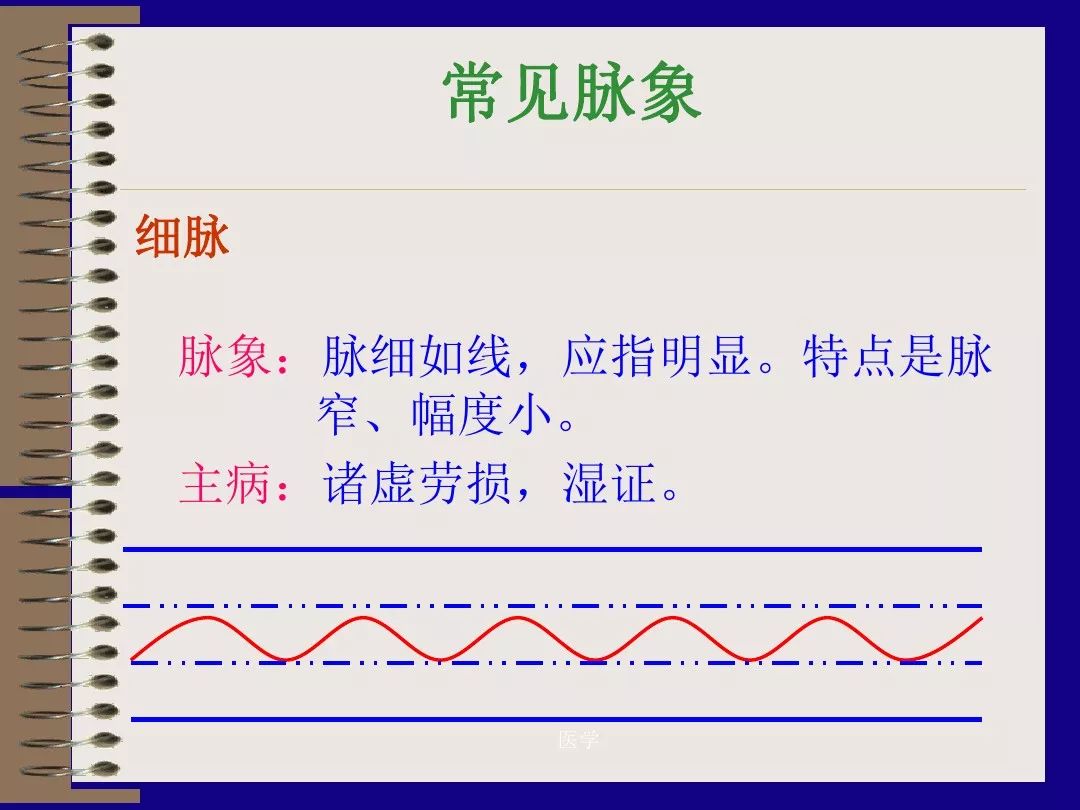

Thin pulse: A pulse that feels thin like a thread, with distinct rises and falls. Indicates: deficiency syndrome, often seen in yin deficiency or blood deficiency. It also indicates dampness. If yin and blood are insufficient, they cannot fill the pulse vessels, or if dampness obstructs the vessels, the pulse will be thin.

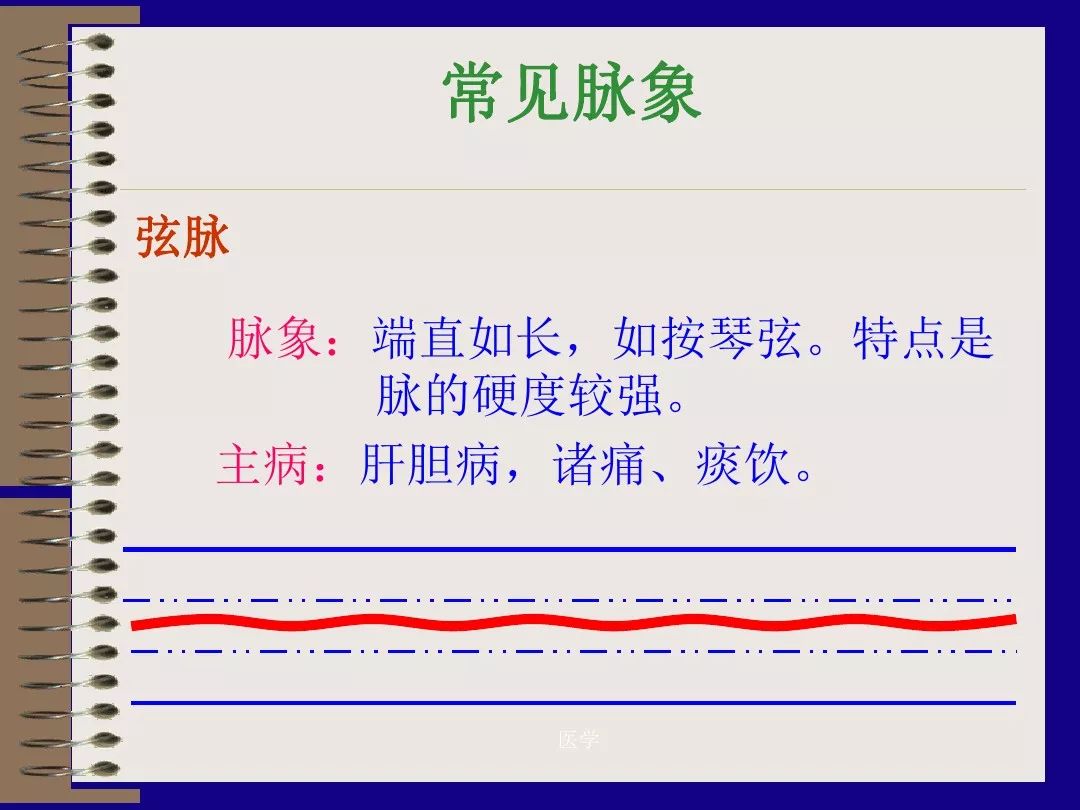

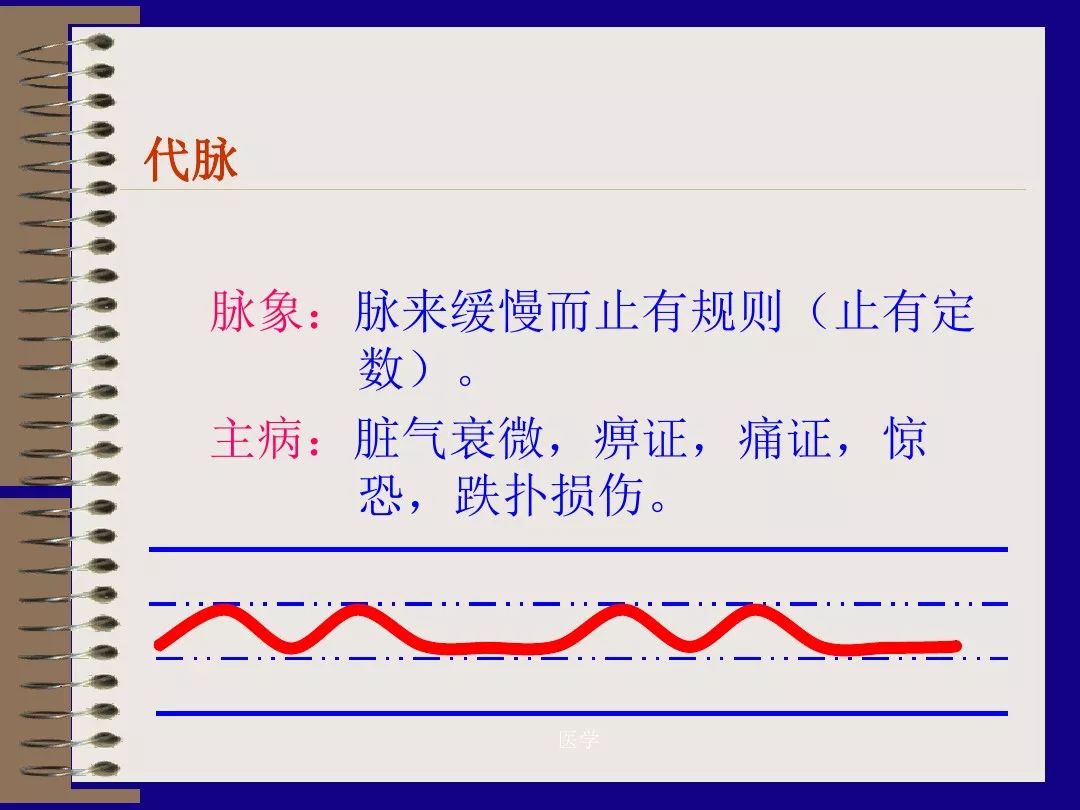

Wiry pulse: A straight and long pulse, firm under the fingers, like pressing a guitar string. Indicates: liver and gallbladder disease, pain syndrome, and phlegm retention. If qi is obstructed, the liver fails to disperse, leading to a wiry pulse. If the disease causes qi disturbance or phlegm retention, it leads to poor qi circulation, resulting in a wiry pulse.

The abdomen is an important part of the body, with the area above the navel belonging to the stomach, below the navel belonging to the intestines, the large abdomen belonging to the spleen, the area around the navel belonging to the kidneys, and the lower abdomen belonging to the liver. By touching and pressing with fingers, one can understand the local temperature, hardness, fullness, swelling, and tenderness, which helps to understand the condition of the organs. Generally, the diagnosis is made by touching and pressing the xu li point (the area where the heart beats).

Deficiency disease: Obvious pulsation, pressing feels strong.

Lung qi deficiency: Pulsation is scattered and rapid.

Liver qi stagnation: Pain in the sides, with pain radiating to adjacent areas.

Liver deficiency: Pain in the sides that feels better when pressed, with weakness when pressing under the ribs.

Blood stasis: Swelling under the ribs, with stabbing pain that resists pressure, and the pain does not move.

Liver cancer: Swelling under the ribs, with an uneven surface when pressed, indicating a warning sign for liver cancer.

Liver qi invading the stomach: Abdominal distension and pain, with pain radiating to the sides.

Stomach cold: Sudden severe stomach pain, with pain that resists pressure, and cold intolerance.

Qi deficiency: Abdominal pain that persists for a long time, with pain that eases or stops when pressed.

Deficiency: Abdominal pain that feels better with warmth and pressure, with a soft and weak abdomen when pressed.

Excess: Abdominal pain with fullness that resists pressure, with a firm abdomen, heavy sound when tapped, or a mass that does not move when pressed.