Acupuncture is a term that encompasses both needling and moxibustion techniques.Needling refers to the insertion of filiform needles into specific acupuncture points on the body, utilizing various needling techniques to treat diseases.Acupuncture has demonstrated remarkable clinical effects, particularly in emergency situations and pain relief, showcasing its ability to produce immediate results. It has evolved over thousands of years and remains widely used in frontline clinical practice today. Reports indicate that the ancient practice of acupuncture has been introduced as a special treatment for battlefield injuries among U.S. troops stationed in Afghanistan, highlighting its significant practical value.

In ancient China, acupuncture emergency techniques included filiform needles, fire needles, finger acupuncture, bloodletting, and moxibustion, with filiform and finger acupuncture being particularly convenient for clinical application. Therefore, this article focuses on a brief overview of their historical development and their close relationship with emergency medicine.

1. The Classic of Needling Emergency Techniques — Filiform Needles

1.1 The Origin of Needling

The original tool for needling was the stone needle, known as bian stone. It appeared approximately 4,000 to 8,000 years ago during the Neolithic period. The name filiform needle originates from the Huangdi Neijing, which has a history of over 2,000 years. According to the Ling Shu, Chapter on the Nine Needles: “Filiform needle, modeled after fine hair, is one inch and six tenths long, primarily used for cold, heat, pain, and obstruction in the collaterals.” This indicates that the filiform needle is named based on its shape and function.

The earliest written record of needling for emergency treatment is found in the idiom “to bring the dead back to life,” which originates from the Shiji (approximately completed in 91 B.C., over 2,100 years ago) in the biography of Bian Que, detailing how Bian Que used needling to perform emergency treatment, stimulating several points to revive the “Prince of Guo” who had “died suddenly.” This account became the earliest successful case of needling for emergency treatment.

Since then, using filiform needles for emergency needling has gradually become a primary measure for physicians throughout the ages.

1.2 The Development of Needling

The outstanding physician of the Eastern Han Dynasty, Hua Tuo, was renowned for his expertise in surgery and acupuncture. As recorded in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, Hua Tuo’s emergency needling involved: “If needling is required, it is usually only one or two points. When the needle is inserted, it is said to be at a certain depth; if so, the patient will say they feel it, and the needle is withdrawn, and the illness is alleviated.” This indicates that Hua Tuo often used only a few acupuncture points (one or two) and that the procedure was simple, yet effective, demonstrating his exceptional needling skills. This also reflects that during the Han Dynasty, using filiform needles for emergency treatment had become a common medical practice.

By the Jin Dynasty, the earliest existing acupuncture text, the Zhenjiu Jia Yi Jing, was completed in 259 A.D. The book consists of twelve volumes and 128 chapters, systematically discussing the pathways of the body’s meridians, the total number of acupuncture points (349), their locations, needling techniques, indications, and contraindications, laying a solid foundation for the further development of acupuncture in later generations. At the same time, the first domestic emergency manual, the “Emergency Formulas for Elbow Disorders”, authored by Ge Hong, was published in 341 A.D., which included descriptions of simple treatments for various sudden injuries and illnesses using needling.

By the Tang Dynasty, the great physician Sun Simiao was the first to propose the concept of “Ah Shi points,” which later led to the development of the concepts and clinical applications of “Tian Ying points” and “pain points” in needling. Furthermore, during the Tang Dynasty, the Taiyi Bureau had already established an independent “Acupuncture Department,” staffed with acupuncture doctors, acupuncturists, and acupuncture students, becoming the earliest medical institution in Chinese history dedicated to training acupuncture practitioners and managing acupuncture clinical practices.

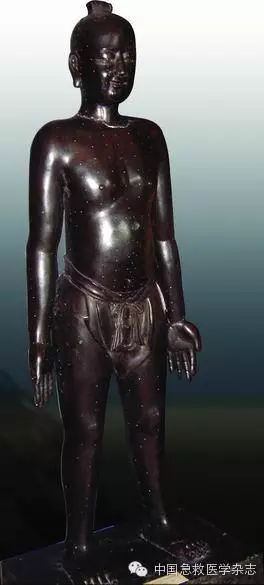

The development of needling techniques advanced significantly during the Song and Yuan Dynasties. In 1026, the Hanlin Medical Officer Wang Weiyi was commissioned to create the “Acupuncture Copper Man,” which was a groundbreaking achievement of its time. The copper man’s size was similar to that of an average adult male, with a removable shell and internal organs. The copper man was engraved with 657 acupuncture points, with the points sealed with wax and filled with water. When needling, if the needle reached a point, water would flow out; if not, the filiform needle could not penetrate. This can be considered the earliest clinical teaching model in China, being both precise and scientifically practical.

Acupuncture Copper Man Model

In the Yuan Dynasty, the famous acupuncturist Dou Hanqing authored the renowned “Guide to Acupuncture Classics” (published in 1295), which included the main content of the “Biao You Fu.” The first line of the “Biao You Fu” states: “The method of rescue, the wonderful use is needling.” This emphasizes that in clinical treatment of critical conditions, needling is the most effective and can often be performed quickly to save lives, thus it should be prioritized over other treatment measures. This was the first time that “needling for emergency treatment” was mentioned with such prominence in a professional text, and it has been widely circulated in later generations.

By the Ming Dynasty, acupuncturists selected for the Tai Hospital had to pass examinations using the acupuncture copper man to prove their theoretical knowledge and technical skills. Additionally, the publication of the “Complete Book of Acupuncture” (approximately published in 1439) and the “Great Accomplishment of Acupuncture” (published in 1601) further promoted the development of needling for emergency treatment and acupuncture studies during the Ming Dynasty.

1.3 The Modern Application of Needling

In 1979, the World Health Organization (WHO) first listed 300 diseases suitable for acupuncture treatment. In 1980, the WHO officially recommended 43 conditions for acupuncture treatment worldwide, of which over 10 were acute conditions (approximately 28%). In November 1996, the WHO updated the list of acupuncture indications from 43 to 64 conditions recommended globally. In 2002, the WHO summarized the effects of acupuncture applications worldwide and expanded the previously recommended 64 conditions to 107 diseases across four categories.

Chinese scholars conducted a systematic analysis of clinical efficacy observations of acupuncture from 1978 to 2005, categorizing reported conditions according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), and identified a modern acupuncture “clinical spectrum” comprising 16 categories and 461 diseases, with acute conditions accounting for 26%. In 2007, needling was officially included as an emergency measure in the domestic “Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Integrated Chinese-Western Emergency Care (Draft).” Since 2009, the U.S. military has also begun to experiment with acupuncture for emergency care in battlefield and frontline hospitals, and related research has confirmed the effectiveness of needling in alleviating pain. Subsequently, “needling for pain relief” became one of the themes at the 13th International Pain Conference held in August 2010, marking the first time in 35 years that the International Association for the Study of Pain chose this topic for its conference content.

Thus, it is evident that the modern application of needling holds great promise.

2 The Preferred Choice for Self-Rescue and Mutual Rescue — Finger Acupuncture

2.1 The Origin and Development of Finger Acupuncture

Finger acupuncture therapy involves using fingers to replace filiform needles for acupoint pressure, also known as “point-pressing therapy.” It employs direct pressure stimulation on acupuncture points on the body using various techniques such as “pressing, pinching, and kneading” to treat certain acute illnesses. Here, fingers and filiform needles serve similar purposes. Finger acupuncture does not require any medical instruments; it can potentially save a life with just bare hands, which is particularly crucial in the first few minutes of a sudden illness, especially before an ambulance arrives, making it the best choice for early self-rescue and mutual rescue.

Finger acupuncture therapy originated from the Huangdi Neijing and has a history of over 2,000 years. According to the Suwen, Chapter on Pain, it states: “Cold qi resides… below, causing blood to stagnate, leading to pain. Pressing it disperses qi and blood, thus alleviating pain.” This is the earliest written record of finger acupuncture therapy and its simple principles.

By the Jin Dynasty, the “Emergency Formulas for Elbow Disorders” pioneered the on-site emergency use of finger acupuncture. For instance, the first chapter, “Methods for Rescuing Sudden Death,” states: “Press the acupoint on the patient’s philtrum to awaken them.” In other chapters, Ge Hong also recommended this method of pressing the philtrum, sometimes combined with “pressing one inch below the heart.” This is the earliest professional record of pressing the philtrum for emergency rescue, which played a crucial role in the further development of finger acupuncture therapy.

In the Ming Dynasty, approximately two-thirds of the conditions treated with acupuncture were acute illnesses. The famous acupuncturist Yang Jizhou documented clinical cases of finger acupuncture therapy in his work, the “Great Accomplishment of Acupuncture.” For example, when treating the severe lower back pain of the official Xu Jing’an, he specifically noted: due to Xu’s “fear of needles,” he used finger acupuncture at the Shenshu point, and the pain immediately decreased. This indicates that the use of fingers instead of filiform needles achieved satisfactory results, showcasing the wonders of finger acupuncture therapy.

The effectiveness of finger acupuncture lies in its similarity to filiform needles, allowing for various techniques to be applied, and achieving the goal of unblocking qi and blood and harmonizing the internal organs through the action of acupuncture points and meridians. Throughout history, physicians have commonly used it to treat conditions such as fainting, stroke, heatstroke, and acute pain.

2.2 The Modern Application of Finger Acupuncture

Finger acupuncture therapy is widely applied in modern clinical practice, covering various specialties including internal medicine, surgery, gynecology, and pediatrics. It is particularly suitable for acute injuries, angina, dysmenorrhea, and infantile crying. In the realm of family emergency care, practical concepts of “hands-on emergency care, acupoints as pathways” have emerged.

Moreover, even in the earliest drafts of the professional “Chinese Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines,” there are references to “pressing the philtrum” to promote resuscitation. Additionally, “pressing the philtrum” has been widely recognized as a technical step in on-site resuscitation by professionals and scholars in the field.

In summary, the brief overview of the ancient and modern applications of acupuncture emergency techniques, including filiform and finger acupuncture, reflects their extensive value in emergency clinical practice. As the global demand for diverse medical and health approaches continues to grow, the simplicity, effectiveness, and affordability of acupuncture in treating acute conditions will become its distinctive advantages for future promotion and application, warranting further exploration and research.

Dear friends, the series of articles on the history of emergency care has been published for seven issues, and we have received much support from many friends who have provided valuable feedback. I cannot thank everyone individually, but I have noted it in my heart! For those who have not spoken up, do you have any thoughts? If so, please don’t forget to leave us a message! Come on, come on, if you like it, please give us a thumbs up ^_^

Next time, you must be curious about the topic of the historical discussion, so let me satisfy your curiosity a little ^_^ The history of “Emergency Care” in China (Series) Part Eight — The Evolution and Progress of Ancient Battlefield Injury Rescue

【Welcome to follow the Chinese Journal of Emergency Medicine】

Click on the blue text above, Chinese Journal of Emergency Medicine, or scan the QR code or search for zgjjyx to add us ^_^

【WeChat Usage Tips】

Many friends are new to WeChat or use it frequently. To help more friends quickly grasp some tips and enjoy the fun of the WeChat era, I have specially organized the following content, hoping it will be helpful to you! If you like us, don’t forget to share with your friends in your circle of friends and spread the joy~~ It’s better to share happiness than to enjoy it alone!