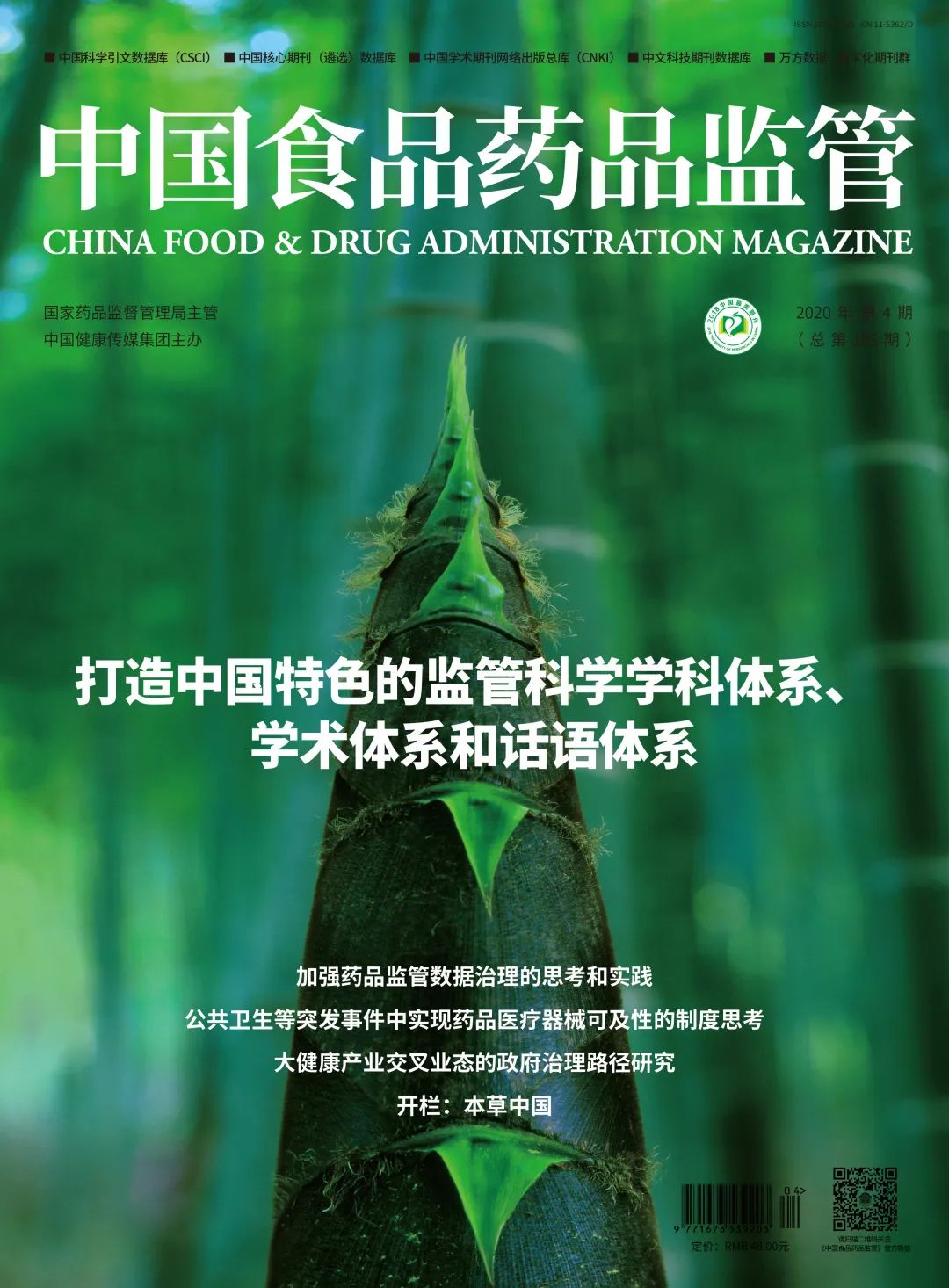

Editor’s Note

The “Herbal China” column is supported by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s “Biodiversity Conservation Special Project (2017) – Investigation of the Current Status of Medicinal Biological Germplasm Resource Conservation”. It is based on the annual “China Traditional Chinese Medicine Resource Development Report” written from the fourth national survey of Chinese medicinal resources, co-founded by the Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences’ Center for Chinese Medicinal Resources, the journal “China Food and Drug Administration”, and the “Zhongyao Ba” WeChat platform. With a top-notch professional team and resources, it is dedicated to popularizing TCM, allowing readers to appreciate the essence of TCM science and culture, and hopes that the establishment of this column can serve the basic research of biodiversity conservation and TCM innovation in our country.

Discussing Herbal Medicine

In recent years, public perception of “Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)” has been highly polarized; those who recognize it revere it, while those who do not remain stuck in outdated views of “quacks” and “wild plant foraging”. These stereotypes often become the focal point of the “East-West medicine debate”. However, contemporary TCM has undergone significant development, with many historical issues greatly improved. Since the introduction of Western learning, TCM has never rejected Western medicine and modern science; many Western medical professionals are also keen to research and develop Chinese medicine, with both fields complementing each other. This has been fully validated in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Nevertheless, there are still many misconceptions about TCM among the public. This column is dedicated to professional TCM popularization, exploring materials from the fourth national survey of Chinese medicinal resources, and narrating the ancient yet modern stories of our herbal medicine from the perspectives of scientific research, cultural essence, and human and ecological civilization.

The term “herb” first appeared in the “Book of Han: Records of Sacrifices” and is now a general term for Chinese medicinal materials, sometimes specifically referring to plant-based medicines, and also denotes books that record these medicines. The brilliance of TCM lies in its ability to combine natural remedies into precise formulas, with careful dosage and efficacy evaluation at the practitioner’s fingertips. Herbs, especially authentic medicinal materials, are highly esteemed by TCM practitioners. Authentic medicinal materials, characterized by strong regional features, refer to those selected through long-term clinical application in TCM, produced in specific regions through specific processes, and are of superior quality and efficacy compared to the same type of medicinal materials from other regions. In a sense, authentic medicinal materials represent the excellent quality of herbs, akin to “brand-name” products in the herbal world.

We respect the ancient understanding of “herbs” while continuously exploring new scientific connotations. As the saying goes, “A region’s soil and climate nurture its people,” each type of Chinese medicine has its specific growth environment. Unlike the past stereotype of people foraging for endangered wild plants, good Chinese medicine emphasizes: mountains, rivers, and streams nurture it, accompanied by flowers, birds, insects, and fish, with humans and nature coexisting harmoniously. In the stride of ecological civilization construction, new herbal stories and the stories of herbal gatherers are born.

Watch how herbalists inherit, protect, and sustainably utilize Chinese herbs in our column “Herbal China”, where you can appreciate the beauty of landscapes and herbs, and feel the light of the fusion of traditional culture and modern science.

Herbal Calendar

Ginseng

(Ren Shen)

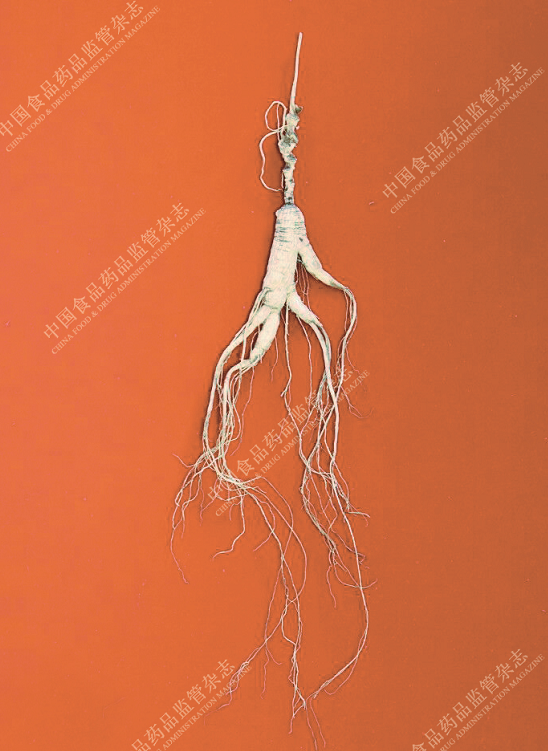

Ginseng prefers shade and avoids strong light. It often grows under layers of vegetation, with only its red seeds possibly revealing its presence. Named for its human-shaped root, it has long been revered as the “King of Herbs”. A single herb can have a lifespan of over a hundred years, inevitably sparking curiosity. Historical records indicate that ginseng has the ability to revive the yang and save patients in critical conditions. This species is unique to the Northeast region, a miraculous life nurtured by heavy snow and long winters.

Origin of the Name Ginseng

Photography: Jin Anqi

Ginseng

(Ren Shen)

Ginseng, originally one of the twenty-eight constellations, is named after the constellation Shen. According to the “Shuo Wen Jie Zi”, it states: “Ginseng, the merchant star, is derived from crystal.” Archaeological discoveries have found pictographs of modern ginseng on bronze vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties, and similar characters appear in other inscriptions. From the evolution of these characters, it can be inferred that “ginseng” and similar terms can also refer to this plant. The Japanese kanji “蔘” comes from the “Yupian”: “Ginseng, the same as ginseng, refers to Korean ginseng.” Ginseng is named for its medicinal part’s shape resembling that of a human.

Currently, most ginseng on the market is primarily cultivated garden ginseng, which is a great tonic for health. However, in terms of medicinal potency, wild ginseng with a lifespan of over 15 years is still superior.

Hand-drawn: Gao Zhi

Ginseng cultivated under shade is called “garden ginseng”. It is the root of the plant Panax ginseng C.A. Mey. It has the effects of tonifying qi, benefiting the spleen and lungs, generating fluids, calming the mind, and enhancing intelligence. It is primarily used for symptoms of qi deficiency, lung, spleen, heart, and kidney qi deficiency, heat disease with qi deficiency and fluid damage leading to thirst, and conditions of qi deficiency with external pathogens or internal heat accumulation.

Ecological diversity is the foundation for ensuring ecological harmony; the coexistence of tonics and toxins is a natural choice. Twisted vines and beautiful flowers belong to the Aconitum genus, which contains certain neurotoxic substances. Ingestion or contact with the juice can lead to nerve paralysis. Toxic components can also be medicinal; in ethnic medicine, they can treat rheumatic pain.

Photography Identification: Que Ling

This is the Northeast Arisaema amurense Maxim, a toxic plant. When its fruits mature, they appear as a cluster of red berries, which can easily be mistaken for wild ginseng. Ingestion by animals may lead to nerve paralysis. It is unclear whether this is a protective mechanism of ginseng’s evolution or a reproductive strategy of Arisaema, or if birds that eat the seeds cannot distinguish between the two fruits, leading to the coexistence of these two medicinal materials, one a great tonic and the other highly toxic.

Photography Identification: Que Ling

Northeast Arisaema, bitter, pungent, warm; toxic. It belongs to the lung, liver, and spleen meridians. It has the effects of dispelling wind and alleviating pain, resolving phlegm and dissipating nodules. It is used for stroke with phlegm obstruction, facial paralysis, hemiplegia, numbness of hands and feet, wind-phlegm dizziness, epilepsy, convulsions, tetanus, cough with phlegm, carbuncles, scrofula, and injuries from falls or snake bites.

Nature’s gifts to humanity are not limitless; we must approach them with reverence, take only what we need, and give back in a timely manner to talk about balance and development. Wild ginseng resources were once over-harvested, leading to the near extinction of century-old ginseng. Since the 1950s, herbalists have spontaneously organized to carry out artificial sowing of wild ginseng, exploring cultivation methods, and protecting suitable ecological environments for ginseng growth. This has developed the under-forest cultivation of wild ginseng, which not only protects the resources of wild ginseng but also preserves the local ecological environment. The people of Jilin Jian’an live off “under-forest ginseng”, accompanied by green mountains and clear waters, leading a prosperous life and creating a model for ecological civilization construction in China.

What are the “Various Ginsengs”?

“Various ginsengs” comes from a mnemonic in the eighteen counteractions of Chinese medicine. “Various ginsengs” refers to four types: ginseng (Ren Shen), sand ginseng (Nan Sha Shen and Bei Sha Shen), salvia (Dan Shen), and black ginseng (Xuan Shen). In addition to these four, the “Compendium of Materia Medica” also records purple ginseng, but the specific identification of purple ginseng is still unverified. Later, we also introduced Korean ginseng, which is similar in efficacy and chemical composition to ginseng, and practitioners also include them in the category of “various ginsengs”. In the “Shennong’s Herbal Classic”, besides the five types of ginseng (Ren, Sha, Xuan, Dan, Zi), there is also “bitter ginseng”. In the later developments of herbal medicine, other classifications such as fist ginseng, party ginseng, hand ginseng, returning ginseng, bright party ginseng, prince ginseng, four-leaf ginseng, and Sichuan bright ginseng have emerged, which are distantly related medicinal plants. Due to their close genetic relationship with ginseng, Western ginseng (American ginseng), bamboo joint ginseng, pearl ginseng, and Vietnamese ginseng are also included in the category of “ginseng” and the eighteen counteractions due to their similar effects.

[End]

Are you “watching” me?