(1) Physiology of the Tongue

1. Tongue Texture: The muscular tissue of the tongue, nourished by blood.

2. Tongue Coating: The white, semi-transparent mucous membrane on the surface of the tongue, formed by the upward movement of stomach qi.

(2) Relationship Between the Tongue and Organs

1. Physiological Connection: The tongue has direct or indirect connections with all five zang and six fu organs, particularly closely related to the heart, spleen, and stomach.

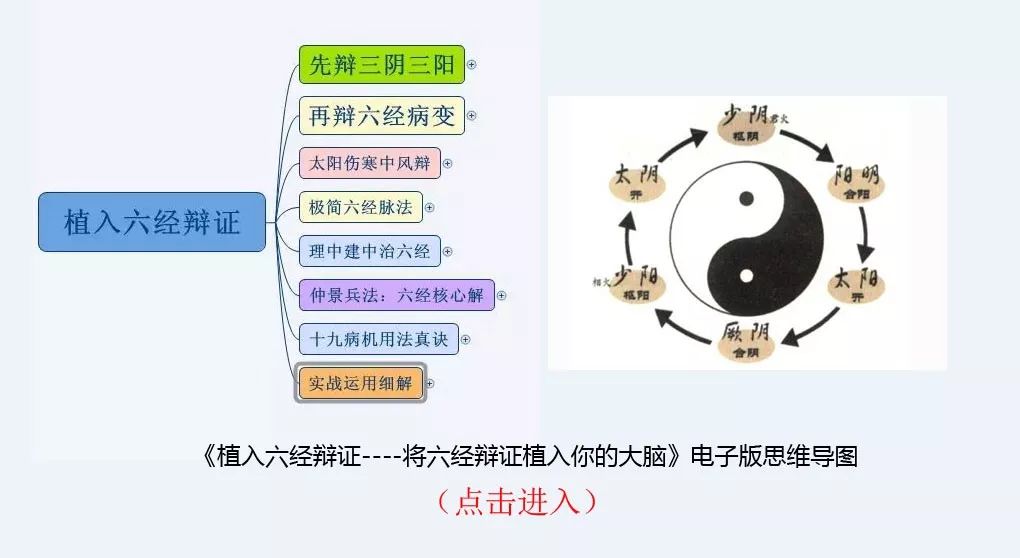

2. The division of tongue areas corresponding to the organs can be done in two ways:

(1) Based on the Stomach Meridian: The tip of the tongue corresponds to the upper jiao, the middle part corresponds to the middle jiao, and the root corresponds to the lower jiao.

(2) Based on the Five Zang: The tip corresponds to the heart and lungs, the sides correspond to the liver and gallbladder, the middle corresponds to the spleen and stomach, the left side corresponds to the liver, the right side corresponds to the gallbladder, and the root corresponds to the kidneys (see Figure 5).

(3) Principles of Tongue Diagnosis

1. The tongue can reflect the function of the heart: The heart governs blood, and the tongue’s texture is nourished by blood; the tongue regulates speech, and the heart governs the spirit, “speech is the voice of the heart.”

2. The tongue can reflect changes in the qi and blood of the organs: In addition to the direct or indirect connection of the organs with the tongue, the heart is the master of all organs, governing the qi and blood functions of the entire body.

3. The taste sensation of the tongue affects the function of the spleen and stomach: The spleen and stomach are the foundation of postnatal life and the source of qi and blood transformation; the kidney meridian is connected to the tongue, and the essence of the five organs is stored in the kidneys, thus the essence of the body is closely related to the spleen, stomach, kidneys, and tongue. Therefore, observing the tongue can reveal changes in the organs.

(4) Methods and Considerations for Tongue Observation

1. Lighting: Sufficient and soft natural light.

2. Posture: The patient should sit upright, mouth open, and extend the tongue naturally.

3. Sequence: First observe the tongue coating, then the tongue texture, observing from the tip to the root.

4. Other factors: The influence of diet, season, time, age, constitution, and tongue scraping or wiping.

(5) Clinical Significance of Tongue Diagnosis

1. Assessing the state of Zheng Qi: Observing the tongue can reveal the presence or absence of qi.

2. Differentiating the depth of the disease: A thin coating indicates a superficial condition, while a thick coating indicates a deeper condition; a crimson tongue indicates heat entering the blood, suggesting a severe condition.

3. Distinguishing the nature of pathogenic factors: A yellow coating indicates heat, a white slippery coating indicates cold, a putrid coating indicates food stagnation and phlegm, and a thick yellow coating indicates damp-heat. A deviated tongue indicates wind pathogenic factors, while spots on the tongue indicate blood stasis.

4. Inferring the progression of the disease: A change from a white to a yellow coating, then to gray or black, indicates the progression of the pathogenic factor from superficial to deep, and the condition worsening from mild to severe; a change from a moist to a dry coating indicates increasing heat and decreasing fluids; a change from a dry to a moist coating indicates the retreat of pathogenic factors and the recovery of fluids.

(6) Main Content of Tongue Observation

1. Tongue Texture: Spirit, color, shape, and state.

2. Tongue Coating: Quality and color of the coating.

(7) Normal Tongue Appearance

Light red tongue with a thin white coating.

(8) Clinical Manifestations and Significance of Pathological Tongue Appearance

1. Tongue Texture

[Clinical Manifestations] Tongue spirit:

(1) Tongue spirit: There are two types, with spirit and without spirit. The presence or absence of spirit is mainly determined by color, luster, and the movement of the tongue.

A tongue with spirit is red, lustrous, and lively (i.e., flexible and soft).

A tongue without spirit is dull, dry, and lacks vitality (i.e., the tongue is stiff and inflexible).

(2) Tongue Color: The tongue color can be classified into five types: pale white, red, crimson, purple, and blue.

(3) Tongue Shape: Includes thickness, youthfulness, swelling, and some special pathological shapes.

Youthfulness is determined by the texture of the tongue. A mature tongue has rough texture and appears old; a youthful tongue has a delicate texture and appears swollen and tender.

Swollen: The tongue is significantly larger than a normal tongue, filling the mouth.

Edematous: The tongue is swollen, filling the mouth, and in severe cases, cannot be closed or retracted.

Thin: The tongue is noticeably smaller and thinner than a normal tongue.

Spots: Spots refer to raised red, white, or black dots on the tongue surface (red star tongue); prickles refer to soft spikes and granules on the tongue surface that not only enlarge but gradually form sharp peaks, which feel prickly (thorny tongue); stasis spots appear as flat spots that do not rise above the tongue surface and are blue-purple or purple-black.

Cracks: The tongue surface has varying numbers of deep and shallow cracks, referred to as cracked tongue.

Smooth: The tongue surface has no coating and is as smooth as a mirror, referred to as a smooth tongue, also known as “mirror tongue” or “glossy tongue.”

Teeth Marks: The edges of the tongue show teeth marks, referred to as teeth-marked tongue, also known as “tooth-impressed tongue,” often seen with a swollen tongue.

Heavy Tongue: The blood vessels under the tongue are swollen, resembling a small tongue growing underneath, hence called heavy tongue. If multiple areas are swollen, it is referred to as “lotus tongue.”

Bleeding Tongue: Bleeding from the tongue is referred to as bleeding tongue.

Abscess on the Tongue: An abscess on the tongue is red, swollen, hard, and painful, often affecting the chin.

Blood Blisters on the Tongue: Small purple blood blisters on the tongue, with a hard base, accompanied by severe pain, are referred to as blood blisters on the tongue.

Ulcers on the Tongue: Ulcers on the tongue, the size of corn kernels, scattered around the tongue, are painful and referred to as ulcers on the tongue.

Fungus on the Tongue: The tongue develops necrotic tissue, initially the size of a bean, gradually enlarging with a small base, resembling “floating lotus,” “vegetable flower,” or “cockscomb,” with a red, rotten surface, producing extremely foul saliva, and severe pain making it impossible to eat.

Sub-lingual Vessels: Normal sub-lingual vessels are faintly visible, located on both sides of the lingual frenulum, at the Jin Jin and Yu Ye points, with two thicker bluish-purple vessels faintly visible. Pathological sub-lingual vessels are thick and swollen, or branched, with blue-purple or purple-black stasis spots.

(4) Tongue State: The state of the tongue refers to its dynamic characteristics, including softness, hardness, tremor, elongation; deviation, shortening, and movement.

Stiffness: The tongue is stiff and rigid, making movement difficult, leading to slurred speech, referred to as “stiff tongue.”

Weakness: The tongue is weak and lacks the strength to extend, referred to as “weak tongue.”

Tremor: The tongue trembles and shakes involuntarily, referred to as “trembling tongue,” also known as “quivering” or “tongue battle.”

Deviation: The tongue is tilted to one side, referred to as “deviated tongue.”

Movement: The tongue extends outside the mouth, referred to as “sticking out the tongue”; if the tongue slightly protrudes and is immediately retracted, or licks the lips up and down or side to side, continuously moving, it is called “playing with the tongue.”

Shortening: The tongue is contracted and cannot extend, referred to as “shortened tongue.”

Elongation: The tongue extends beyond the mouth, and retracting is difficult, or cannot retract, referred to as “elongated tongue.”

Tongue Paralysis: The tongue feels numb and cannot move, referred to as “tongue paralysis.”

[Clinical Significance] Observing the tongue texture is crucial for diagnosing the vitality of the organs and assessing the prognosis of diseases.

(1) Tongue Spirit: A tongue with spirit indicates a better prognosis, while a tongue without spirit indicates a poor prognosis.

(2) Tongue Color: The clinical significance of tongue color must be closely combined with luster for assessment.

Pale White Tongue: Indicates deficiency, cold, or both qi and blood deficiency; a pale white and moist tongue is often seen in yang deficiency, while a thin, pale, and lustrous tongue indicates both qi and blood deficiency.

Red Tongue: Indicates heat syndrome, with distinctions between deficiency and excess. A red tongue with prickles or a thick yellow coating often indicates excess heat; a red tongue with little coating, cracks, or a bright red tongue without coating indicates deficiency heat.

Crimson Tongue: Indicates differentiation between exterior and interior conditions. An exterior condition with a crimson tongue indicates warm disease heat entering the blood; an interior condition with a crimson tongue indicates yin deficiency with excess fire, often with little coating and dryness; if it is bright red and moist, it indicates blood stasis.

Purple Tongue: Indicates differentiation between cold and heat conditions. A purple tongue with crimson indicates heat syndrome, dry and lacking fluids; a pale purple tongue indicates cold syndrome, moist and hydrated.

Blue Tongue: Indicates cold stagnation and blood stasis. A completely blue tongue indicates cold in the liver and kidneys, while a blue tongue on the sides indicates internal blood stasis.

(3) Tongue Shape: The shape of the tongue indicates complex conditions and must be assessed based on specific situations.

Youthfulness: A youthful tongue indicates deficiency, while a mature tongue indicates excess conditions.

Swollen Tongue: Generally caused by water retention and phlegm, but can differ between excess and deficiency. In excess conditions, the disease is in the spleen and stomach with damp-heat and phlegm; in deficiency conditions, the disease is in the spleen and kidney yang deficiency, with a pale and swollen tongue.

Edematous Tongue: A bright red tongue indicates heart and spleen heat; a purple tongue indicates heat combined with alcohol toxicity or congenital tongue vascular malformations.

Thin Tongue: Indicates qi and blood deficiency, with a pale color; indicates yin deficiency with excess fire, with a red and dry appearance.

Spots: Red, black, or white spots indicate heat toxins in the blood. Red spots are often seen in heat toxins, damp-heat accumulation in the blood, or heat toxins attacking the heart. White spots are often due to insufficient qi, while black spots are due to blood heat and stagnation.

Cracks: Indicate three conditions: (1) Excess heat injuring yin (red color), (2) Blood deficiency leading to lack of nourishment (pale color), (3) Spleen deficiency with dampness (pale color, swollen tongue with teeth marks).

Smooth Tongue: Indicates a critical condition where stomach qi is about to fail. If pale and lustrous, it indicates extreme qi and blood deficiency, severe damage to the spleen and stomach; if red and lustrous, it indicates excess fire and depletion of stomach and kidney yin fluids.

Teeth Marks: Indicates spleen deficiency with excess dampness. If pale and moist, it indicates excess cold; if pale red, it indicates spleen deficiency and qi deficiency.

Heavy Tongue: Indicates heart fire syndrome, often seen in children.

Bleeding Tongue: Indicates heart fire, stomach heat, liver fire, or spleen deficiency.

Abscess on the Tongue: Indicates heart fire or accumulation of heat in the spleen and kidneys.

Blood Blisters on the Tongue: Indicates heart and spleen fire toxicity.

Ulcers on the Tongue: Indicates heat toxins in the heart or excess fire due to yin deficiency.

Fungus on the Tongue: Indicates heart and spleen stagnation with heat and fire.

Sub-lingual Vessels: Blue-purple and swollen sub-lingual vessels indicate qi stagnation and blood stasis.

(4) Tongue State: Refers to the dynamic characteristics of the tongue, including softness, hardness, tremor, elongation; deviation, shortening, and movement.

Stiffness: Indicates heat entering the pericardium, high fever, fluid damage, phlegm obstruction, or stroke and its precursors.

Weakness: Indicates prolonged illness with qi and blood deficiency, or extreme yin deficiency with recent heat damage.

Tremor: Indicates three conditions: (1) Deficiency syndrome, seen in qi, blood, and fluid deficiency and yang deficiency; (2) Extreme heat generating wind; (3) Alcohol toxicity.

Deviation: Indicates stroke or its precursors. In chronic illness, it often indicates stroke sequelae; in acute illness, it often indicates liver wind spasms.

Movement: The tongue extends outside the mouth, referred to as “sticking out the tongue”; if the tongue slightly protrudes and is immediately retracted, or licks the lips up and down or side to side, continuously moving, it is called “playing with the tongue.” Both indicate heat in the heart and spleen. Sticking out the tongue is often seen in heart and spleen heat, while playing with the tongue is often seen in precursors to wind or congenital intellectual disability in children.

Shortening: Indicates a critical condition, seen in cold stagnation, phlegm obstruction, extreme heat generating wind, or extreme qi and blood deficiency.

Elongation: If the tongue extends and cannot retract, it indicates a critical condition. If it can retract and is moist, the condition is less severe. This can be seen in phlegm heat disturbing the heart and prolonged qi deficiency.

Tongue Paralysis: Indicates wind qi combined with phlegm obstructing blood vessels, or blood deficiency leading to wind movement and lack of nourishment.

2. Tongue Coating

[Clinical Manifestations] Mainly observe changes in coating color and quality.

(1) Coating Color: The main colors are white, yellow, gray, and black. Additionally, it is important to distinguish between moist and dry qualities and the transformation between colors.

(2) Coating Quality: Refers to the shape and quality changes of the tongue coating. It can be classified into thickness, partial or full, peeling, and changes in moisture and dryness, as well as true and false appearances.

[Clinical Significance] The color and quality of the coating can be summarized as follows:

(1) Coating Color:

White Coating: Generally indicates exterior conditions or cold conditions. However, in special cases, it can also indicate heat conditions, seen in epidemics or internal abscesses as “accumulated powder coating” or “powder white coating,” and can also be seen in warm diseases transforming into heat rapidly or mistakenly taking warming herbs leading to “rough, cracked coating.”

Yellow Coating: Generally indicates interior conditions or heat conditions. However, attention should be paid to the changes in coating color and the transformation between yellow and white coatings, as well as the moisture and dryness of the coating.

The changes in the depth of yellow coating generally parallel the development of heat pathogens, i.e., if the coating changes from light yellow to deep yellow, it indicates the heat pathogen is becoming more severe; if the yellow coating gradually becomes lighter, it indicates the heat pathogen is becoming milder.

Transformation between yellow and white coatings: A gradual change from white to yellow indicates the transition from an exterior condition to an interior heat condition. Wind-heat exterior conditions can also initially present as a thin yellow coating.

Moisture and dryness of yellow coating: A yellow coating that is dry indicates excessive heat damaging fluids, while a yellow coating that is moist indicates yang deficiency with water dampness not transforming.

Gray Coating: Indicates interior conditions, but can be differentiated between cold and heat: gray coating that is dry indicates interior heat conditions, seen in exterior heat diseases or internal injuries with yin deficiency and excess fire; gray coating that is moist indicates interior cold conditions, seen in phlegm retention or cold damp obstruction.

Black Coating: Often seen in severe epidemic diseases, indicating interior conditions, with differentiation between cold and heat: black and dry coating indicates extreme heat; black and moist coating indicates extreme cold conditions.

Additionally, there are green coating and moldy coating.

Green Coating: Transforms from white coating, indicating similar diseases as gray and black coatings, but does not indicate cold conditions, seen in epidemics or damp-warm diseases.

Moldy Coating: Indicates prolonged damp-heat or internal heat stagnation, seen in damp-heat combined with heat stroke or damp-heat injury.

(2) Coating Quality:

Thickness: Indicates the depth of the pathogenic factor. A thin coating indicates exterior conditions or light internal injuries; a thick coating indicates interior conditions with severe pathogenic factors, often caused by phlegm, dampness, or food stagnation.

The dynamic significance of the transformation between thick and thin coatings: If the coating changes from thin to thick, it indicates the transition from an exterior condition to an interior condition, with the pathogenic factor becoming more severe; if the coating changes from thick to thin, it indicates the pathogenic factor is becoming milder, with the internal condition resolving.

Partial or Full: Can indicate the location of the disease. A full coating indicates scattered pathogenic factors, seen in phlegm and dampness obstructing conditions. Localized coatings can be divided into inner, outer, middle, and both sides:

Outer coating (tip of the tongue): Indicates the pathogenic factor has not deeply entered the interior, but the stomach qi is already damaged; inner coating (root of the tongue) indicates stagnation in the stomach; middle coating indicates phlegm and food stagnation; little coating indicates insufficient stomach yang and kidney yin, with both yin and qi being damaged. Coatings seen on both sides of the tongue indicate half exterior and half interior conditions, or liver and gallbladder damp-heat diseases.

Peeling: Different forms of peeling can be classified as “smooth peeling tongue” (mirror tongue), “flower peeling tongue,” “map tongue,” and “similar peeling tongue.” The clinical significance mainly lies in assessing the survival of stomach qi and yin and the prognosis of diseases.

Smooth peeling tongue indicates severe damage to stomach qi and yin; flower peeling tongue indicates phlegm and dampness not transforming, with damage to the righteous qi; similar peeling tongue indicates prolonged illness with damage to qi and blood; thick coating with peeling indicates dryness; and signs of liquid depletion.

Growth and Decline: Mainly observe the struggle between the righteous and the evil, assessing changes in prognosis. In addition to observing the transformation of growth and decline, it is especially important to pay attention to the timing of the transformation.

The timing of coating transformation is based on gradual changes and sudden changes:

Gradual changes indicate a favorable condition; sudden changes indicate an unfavorable condition, with sudden thickening indicating a rapid decline in righteous qi and a rapid increase in pathogenic factors, while sudden disappearance indicates a critical condition.

Retreating coating and regrowth changes: If the coating does not regrow, it becomes a “mirror tongue,” indicating severe depletion of stomach qi and yin; if there are multiple areas of peeling, it becomes flower coating, also indicating an unfavorable condition; if the coating suddenly retreats but the tongue surface remains dirty or moist, or shows vermilion spots or patterns, and thick coating regrows within a day or two, it indicates excessive dampness and stagnation of the righteous and evil.

Moisture and Dryness: Based on the moisture of the fluids, it can be classified into “slippery coating,” “dry and bitter coating,” “powder coating,” and “dry and cracked coating.” The clinical significance lies in understanding the survival of fluids.

Moist coating indicates fluids are not damaged; slippery coating indicates yang deficiency with phlegm and dampness stagnating; dry coating indicates excessive heat damaging fluids, deficiency of yin fluids, or yang deficiency failing to transform fluids, with excessive cases of heat damaging fluids.

Special conditions of moist and dry coatings: Moist coatings indicate heat conditions, seen in heat pathogens entering the blood; dry coatings indicate dampness, seen in damp pathogens entering the qi level, failing to transform fluids.

Putrid Coating: Clinically divided into “putrid coating,” “floating dirt coating,” “pus putrid coating,” “moldy coating,” “greasy coating,” and “dirty coating (turbid coating)”. Indicates the changes in yang qi and dampness.

Putrid coating indicates excess yang heat, steaming and rising dampness; seen in food stagnation, internal abscesses, and damp-heat oral ulcers.

If the coating changes from stagnation to putrid, and gradually retreats to a thin floating coating, it indicates the righteous qi is overcoming the evil, suggesting the disease is retreating.

Pus putrid coating indicates severe pathogenic factors in lung abscesses, stomach abscesses, liver abscesses, and toxic conditions.

Moldy coating indicates the transformation of stomach yin into putrid.

Greasy coating indicates the accumulation of pathogens, with yang qi being suppressed. Seen in dampness, phlegm, food stagnation, damp-heat, and stubborn phlegm.

Greasy coating should also pay attention to the changes in yellow and white: yellow greasy indicates heat (phlegm heat, damp-heat, summer heat, damp-warm), food stagnation, and damp phlegm obstructing the qi; white greasy coating indicates moisture and dryness: slippery and moist indicates cold dampness; if it is powdery, it indicates seasonal pathogens combined with dampness; if it is not dry, it indicates spleen deficiency with excessive dampness; if it is sticky, it indicates damp-heat in the spleen and stomach.

True and False: True coating is also known as “rooted coating,” while false coating is known as “unrooted coating.” The clinical significance lies in assessing the severity of the disease and prognosis.

True coating is seen in the early and middle stages of disease, indicating deep and severe pathogenic factors; in the later stages, it indicates a favorable condition; thick coating covering new coating indicates a sign of recovery.

False coating, depending on its growth state and color, can be classified: false coating is not rootless, it is normal, seen in morning coating, and after eating, the coating retreats like a normal person; if the coating retreats little or not at all, it indicates internal deficiency. Thick coating without roots and new coating not growing indicates damage to stomach qi, seen in excessive consumption of cold items damaging yang, or damp-heat yang herbs damaging yin. The coating color is easy to retreat (observed by scraping or wiping), indicating the pathogenic factor is light.

Appendix: Tongue Diagnosis Mnemonics

(1) The tongue and coating must be distinguished; coating is dirt, while the tongue is the essence. Coating reflects qi diseases, while the tongue reflects blood diseases; yin and yang, exterior and interior, cold and heat, deficiency and excess. The depth of pathogenic factors can be observed through the coating; the deficiency and excess of the organs can be identified through the tongue texture.

(2) Changes in tongue coating have specific areas: the tip corresponds to the heart and lungs, the center corresponds to the stomach, the root corresponds to the kidneys, the sides correspond to the spleen and earth, and the sides of the tongue correspond to the liver and gallbladder; another method is to observe the three jiao divisions, with the tip above and the root below, and the center corresponding to the middle jiao.

(3) Distinguishing tongue fluids: moist, dry, slippery, and rough. Moisture is normal, while thickness indicates dampness. Moisture with abundant fluids indicates slippery coating; rough indicates floating and coarse. Dryness indicates fluid depletion.

(4) Presence or absence of spirit is determined by luster and dryness. Luster indicates nourishment, with fluids evenly distributed; red and bright indicates rich qi and blood. Dullness indicates lack of blood color. If the righteous qi is about to be exhausted, fluids are deficient and dry, indicating a critical condition.

(5) Red tongue indicates heat, with many distinctions. Heart fire is rising, with a red tip. Red on the sides indicates liver and gallbladder heat. In the early stages of warm disease, the tip and sides may be red; seen in various diseases, indicating heart and liver colors; headaches, insomnia, irritability, and constipation. Bright red also has distinctions; in warm diseases, it indicates severe heat, while in various diseases, it indicates yin deficiency. A dry red tongue indicates depletion of yin fluids, with a smooth and tender appearance, indicating a critical condition.

(6) Crimson tongue indicates warm heat entering the blood. Pure crimson and bright indicate excessive heat. Dry and withered indicates depletion of kidney yin; often accompanied by dryness of the throat. Indicates a critical condition. There is also a type of crimson tongue with little coating, even cracked, indicating imminent depletion of yin fluids. A crimson tongue with a greasy appearance, resembling coating, indicates dampness and turbidity, with a tendency to open up. Observing the tongue indicates the presence of fluids; if fluids are damaged, damp heat steams, turbidity obstructs, and fluids are depleted.

(7) Purple tongue indicates disease, with both yang and yin; with or without coating, the main distinction is made. Moisture and dryness, deep or shallow, full tongue or spots indicate different diseases, with varying severity. Yellow coating with purple tongue indicates accumulated heat in the organs; if accompanied by dryness, it indicates urgency. A blue-purple tongue with slippery coating indicates extreme cold. In the early stages of cold damage, it directly affects the three yin. Blood stasis diseases present with a purple tongue, often moist, or with gray coating; severe cases may cover the entire tongue, while mild cases may show spots; prolonged pain leads to stasis. Alcoholics often have purple spots on the tongue. A white slippery center indicates drunkenness or cold damage.

(8) Blue changes resemble purple tongue; still able to develop coating, indicating righteous qi is not exhausted. A bright blue tongue without coating indicates a lack of vitality, indicating a critical condition. A blue tongue not covering the entire surface indicates different conditions: epidemic filth, with powdery white coating; yellow greasy coating indicates damp-heat; slippery blue coating indicates phlegm.

(9) Black indicates severe illness, with both yin and yang: moist and slippery indicates extreme cold; rough and dry indicates extreme heat. Blood has already deteriorated. In ancient times, it was referred to as a death sign. Accurate differentiation can lead to early rescue, possibly achieving recovery.

(10) Aging and youthfulness must also be analyzed: a stiff and aged tongue indicates excessive heat stagnation, with spirit still present, often indicating excess; a swollen and weak tongue indicates phlegm dampness.

(11) Lines, peeling, and prickles each have their signs: lines on the tongue texture resemble shattered porcelain, indicating blood deficiency and severe heat, also seen in yin deficiency. Peeling indicates a smooth area, with a clean surface, indicating yin damage, often difficult to fill. Severe cases may lead to complete tongue peeling. A tongue with prickles may have black or yellow spots, regardless of the front or back, indicating dryness. A swollen tongue indicates phlegm dampness and heat. A thin and withered tongue indicates various deficiency conditions.

(12) Normal tongue texture is soft and flexible, moving freely, with harmonious qi and blood. A weak crimson tongue indicates extreme deficiency, with a pale red color. A stiff tongue indicates wind-fire phlegm; a stiff tongue indicates paralysis, with heart and spleen wind; red and swollen indicates extreme heart fire; phlegm swelling indicates gray coating. The tongue should extend and relax naturally; if it cannot extend, it indicates weakness. If the tongue wants to extend but is tethered, it indicates dryness, cold, phlegm, or other conditions affecting the meridians, leading to stiff speech. Dryness and cold indicate wind phlegm adhesion. The tongue should extend and relax, indicating a critical condition; if it suddenly shortens, it indicates dryness and redness; if it is white and moist, it indicates cold stagnation; if it is sticky, it indicates phlegm retention.

(13) True and false must also be distinguished, as they relate to the survival of qi. True coating grows from the tongue, evenly spread across the surface. False coating is thick and appears clean around the edges, as if painted on the tongue surface.

(14) Thick and thin coatings indicate internal and external pathogenic factors. Exterior cold is generally thin, with various conditions; thick coatings indicate internal pathogenic factors, often due to excess. Putrid coatings are thick and can be removed, indicating the righteous qi is overcoming the evil. Greasy coatings are sticky and do not easily come off, indicating phlegm dampness obstructing the interior, with yang being suppressed. Putrid coatings resemble mold or pus, indicating damage to stomach qi or internal abscesses.

(15) Coating covering the entire tongue indicates scattered pathogenic factors, with thin white indicating exterior conditions; white greasy indicates phlegm, requiring caution in treatment to prevent changes. If the coating appears localized, it indicates specific areas of concern. Changes in coating color can indicate the direction of the disease: from white to yellow indicates the transition from exterior to interior; yellow to gray or black indicates worsening conditions. If the coating suddenly retreats without gradual change, it indicates the pathogenic factor has penetrated deeply, indicating a critical condition.

(16) Food can stain the coating, requiring differentiation. Loquats and olives can turn yellow or black. Sweet, sour, and salty foods, as well as fruit juices, can stain the coating, often leading to a white and moist tongue.