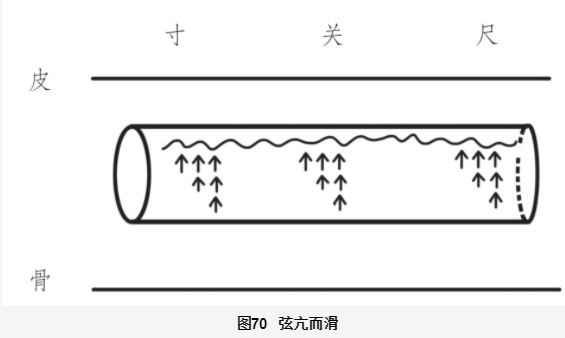

The Xian Mai (Xian Pulse) is the most common and representative pulse type in clinical practice, characterized by its variability. It resembles a taut string, indicating tension, tightness, contraction, and a lack of softness and fluctuation. It can be seen in both cold and heat conditions, as well as in cases of liver and kidney yin deficiency and water retention. How can we understand the Xian pulse using a conduit model?

Imagine a hollow soft rubber tube that becomes taut when filled with air; this is analogous to the formation of the Xian pulse.

The Xian pulse arises from increased pressure within the conduit, causing a blockage in the exchange between the conduit and surrounding tissues. For instance, when a person’s emotions change, especially during anger, the pressure within the conduit can suddenly increase, leading to a Xian pulse. During times of tension and repression, nerve reflexes cause the ends of the conduit and tissues to tighten, further increasing pressure and making the Xian pulse more pronounced. In modern society, as stress levels rise, the occurrence of the Xian pulse has become more common.

However, the formation of the Xian pulse is not solely related to emotions. Next, we will analyze different types of Xian pulses.

1. Zheng Xian Mai (Normal Xian Pulse)

This is the most clinically significant pulse type.

Before discussing the Zheng Xian pulse, we must introduce two important concepts: Fluid Balance and Blood-Water Exchange Balance.

(1) Fluid Balance

Life originated from seawater, evolving from single-celled organisms into complex life forms. Every cell and tissue must survive on the nourishment of water. Similarly, all metabolic processes in the human body rely on water as a medium, highlighting its dominant role.

What nourishes can also harm. Water is the fundamental fluid for life and is also a significant factor in the development of diseases.

For every cell and tissue, both insufficient and excessive water can be detrimental. The body’s ability to accommodate water is related to the current state of its yang qi. When the yang qi of the body’s tissues and cells is balanced with water, the liquid can be transformed into jin ye (body fluids) for utilization. We can refer to this state as the “Fluid Balance” state.

If there is too much liquid, exceeding the burden of yang qi, the excess will become waste water, known as “yin” (pathogenic water). This not only cannot be utilized but will also accumulate in various layers and parts of the body, leading to various diseases.

Many people may not believe that numerous diseases stem from excessive water intake or incorrect drinking methods (e.g., drinking large amounts of water when thirsty). Recently, I treated a patient with severe palpitations and premature beats. According to his description, the onset was due to drinking large amounts of water after discovering he had kidney stones. Although the stones were expelled, he developed heart disease and required daily medication even after radiofrequency ablation treatment, with symptoms still poorly controlled. I prescribed a formula based on Ling Gui Zhu Gan Tang (Poria, Cinnamon, Atractylodes, and Licorice Decoction), which helped control his symptoms and gradually reduce his need for Western medication.

(2) Blood-Water Exchange Balance

Here, the term “blood” does not equate to the Western medical concept of blood. Instead, it refers to the jin ye within. We can understand it as follows: water, under the influence of yang qi, carries various energy nutrients to become jin ye, which nourishes the exterior as qi and the interior as blood. After fulfilling its nourishing role in the blood, jin ye will exit from the blood. The Blood-Water Exchange Balance refers to a state where the flow of water in and out of the interior is balanced and smooth. When the flow of jin ye becomes stagnant, leading to the formation of stasis blood, the entry of water into the interior will be obstructed, disrupting this balance.

Stasis blood syndrome can obstruct the entry of jin ye into the blood, which is why many stasis blood syndromes are accompanied by symptoms of dryness and heat, such as irritability, dry lips, and yellow urine. Clinically, we often see patients with signs of deficiency and cold, yet they also exhibit obvious symptoms of dryness and heat. This is because, on one hand, the deficiency of yang qi fails to vaporize jin ye adequately, leading to insufficient jin ye; on the other hand, the presence of stasis blood obstructs the entry of jin ye into the blood, further exacerbating the deficiency of nourishment in the blood. This results in the simultaneous presence of deficiency, cold, and dryness in the blood.

Based on my clinical experience, I believe there are three pivotal points in the body’s blood-water exchange: the upper, middle, and lower jiao. When stasis blood syndrome is severe and occurs at these pivotal points, the concept of blood-water exchange becomes particularly important.

In the upper jiao, blood stasis can lead to the reflux of jin ye, resulting in excessive sweating, primarily in the upper body, which worsens with tension. If jin ye fails to nourish the blood, it can lead to insomnia and vivid dreams, treated with Xue Fu Zhu Yu Tang (Blood Mansion Decoction).

In the middle jiao, blood stasis can lead to reflux of jin ye, resulting in diarrhea. Wang Qingren used his Ge Xia Zhu Yu Tang to treat chronic diarrhea and morning diarrhea. Zhang Zhongjing’s Shang Han Lun contains a passage about using Huang Qin Tang to treat diarrhea: “When Taiyang and Shaoyang combine and cause diarrhea, use Huang Qin Tang; if there is vomiting, use Huang Qin plus Ban Xia and Sheng Jiang Tang.” This illustrates how stasis blood and heat can lead to diarrhea. From this perspective, we can understand what is meant by “heat binding and flowing sideways” and why Da Cheng Qi Tang is used for treatment.

In the lower jiao, blood stasis can lead to bladder blood retention, causing symptoms such as abdominal distension, frequent urination, and dry stools, treated with Tao Ren Cheng Qi Tang or Shao Fu Zhu Yu Tang. Once we grasp the concepts of “Fluid Balance” and “Blood-Water Exchange Balance,” we can see that the entire Shang Han Lun revolves around how to regulate these two core issues.

The Shang Han Lun provides a qualitative description of the Xian pulse.

In the Jin Gui Yao Lue (Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Cabinet), it states: “A double Xian pulse indicates cold; a偏 Xian pulse indicates water retention; a沉而弦 pulse indicates internal pain from suspended water.” This indicates that the Xian pulse is associated with pathogenic water.

This type of Xian pulse caused by pathogenic water is what I refer to as the Zheng Xian pulse. How can we understand the Zheng Xian pulse from the conduit model?

The main pathways for water in the body are through the skin and urine. When the drainage functions of these two systems are impaired, the concentration of water in the cells increases. The main sources of water in the body are through diet; improper eating habits, sudden excessive water intake, or frequent consumption of fruits can also increase the concentration of water in the cells. An increased concentration of water in the cells will permeate into the conduits, ultimately leading to an overload of water in the conduits and cells, which cannot be utilized, resulting in pathogenic water. This pathogenic water, when blocked in the conduits, increases pressure, even affecting normal exchanges between the conduits and cells, leading to the formation of the Zheng Xian pulse and its pathogenesis.

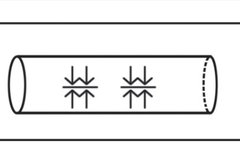

We represent the pulse diagram of the Zheng Xian pulse as follows:

The diagram of the Zheng Xian pulse reflects increased tension in the conduits, with exchanges in and out being obstructed.

If the image is insufficient to fully describe the specific morphology of the Zheng Xian pulse, what should the tactile sensation be like?

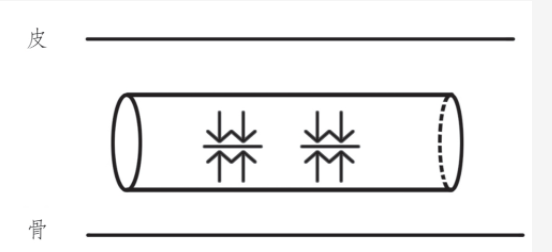

The Zheng Xian pulse should have the following characteristics: when the hand presses on the pulse skin, the pulse shape exhibits a straight and long characteristic; when the finger presses into the conduit, there is no slippery sensation, no weakness, no feeling of diminishing strength, and no sensation of qi pushing against the fingertip. Instead, there is a feeling of fullness within the conduit, but it does not feel as tight and lacking in elasticity as a solid pulse. The specific sensation is akin to a conduit filled with water. Describing it in words may still be elusive. We can imagine that a typical pulse resembles an empty tube, while the Zheng Xian pulse resembles a water-filled tube that has a certain pressure, as shown in the following diagram:

When the Zheng Xian pulse is present, patients often experience symptoms such as chest tightness and cough related to pulmonary water retention;

When the left cun exhibits a Zheng Xian pulse, patients often experience palpitations and irregular heartbeat related to cardiac water retention;

When both cun pulses exhibit a Zheng Xian pulse, patients may experience symptoms such as shortness of breath, upward qi counterflow, cough, a sensation of foreign body in the throat, and difficulty swallowing related to water retention obstructing the upper jiao. The treatment for upper jiao water retention is Ling Gui Zhu Gan Tang. This formula, while composed of gentle herbs, is a treasure for elderly health, as it can clear water retention from the upper jiao, significantly reducing the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Middle jiao water retention is indicated by a Zheng Xian pulse in the guan pulse. If the Zheng Xian pulse appears in the right guan, it typically indicates symptoms of abdominal distension, borborygmi, diarrhea, and belching related to gastrointestinal water retention, treated with Sheng Jiang Xie Xin Tang or Shen Zhuang Tang. If the Zheng Xian pulse appears in the left guan, it usually indicates symptoms such as poor appetite, bitter mouth, and chest and flank distension, treated with Chai Hu formulas.

Lower jiao water retention is typically indicated by a Zheng Xian pulse in the chi pulse, often accompanied by symptoms such as abnormal urination, low back pain, cold feet, cold lower back, cold buttocks, dizziness, and a heavy head, treated with Wu Ling San, Zhen Wu Tang, or Fu Zi Tang.

Clinical practice has shown that patients exhibiting Zheng Xian pulses in two or more pulse positions often eventually present with a weak pulse in the right guan after treatment, necessitating the use of Li Zhong Tang to conclude treatment, which fully demonstrates that water is generated by the spleen and stomach. One cannot live without water, but one can also be harmed by it. The above discussion pertains to the occurrence of a Zheng Xian pulse in a single position while other positions are generally normal. Clinical applications must also be analyzed based on specific circumstances.

2. Qi Xian Mai (Qi Xian Pulse)

The Xian pulse overview mentioned that when a person is in a state of suppressed anger, conduit pressure increases, and the exchange within the conduit is obstructed by “qi,” leading to the emergence of the Xian pulse. We can borrow the term from the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (Shen Nong’s Classic of Materia Medica) to refer to this state of “qi obstruction” as “Jie Qi”, and we call the Xian pulse in this state the “Qi Xian pulse”.

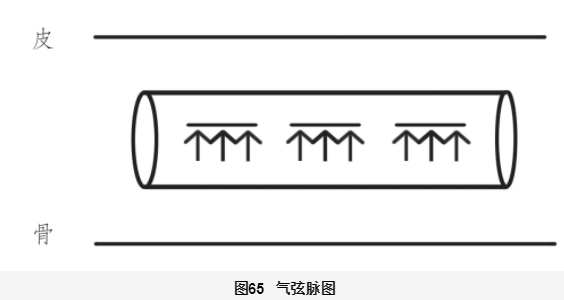

We can imagine a person in a state of rage, with blood vessels dilated and veins bulging, corresponding to an increased pressure within the circulatory conduits. The diagram of the Qi Xian pulse is represented as follows:

What is the tactile sensation of the Qi Xian pulse like?

When we press our fingers on the pulse skin, we feel the straight and long sensation of the Xian pulse. When pressing into the conduit, we feel that there is strength beneath the fingers, but it is not slippery, not properly Xian, and not solid. When pressing towards the center of the conduit, we feel a force pushing our fingers away, similar to an angry person rejecting someone’s approach.

The Qi Xian pulse represents excessive and stagnant qi.

When the Qi Xian pulse appears in the floating position, we can use some floral and leaf qi-regulating herbs for treatment, such as Perilla leaves, Perilla stems, Tangerine leaves, Green tangerine, Aged tangerine peel, Mint, and Rose petals; when the Qi Xian pulse appears in the middle or deep positions, we can choose to use Si Ni San for treatment.

Clinically, the Qi Xian pulse is often seen in the guan pulse, and the guan pulse tends to be larger than in other positions.

3. Xian Ruo Mai (Weak Xian Pulse)

We have discussed the Qi Xian pulse characterized by excessive anger and qi. Correspondingly, there is a type of Xian pulse characterized by repression, tension, and weak qi, which we refer to as the Weak Xian pulse.

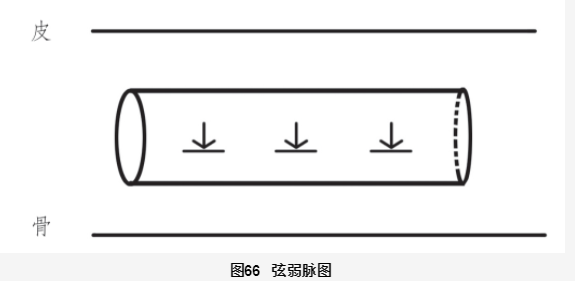

There is often a category of patients who have a weak constitution, gentle personality, and frequently swallow their anger, holding in their feelings. They often remain in a state of tension and defense, which can be imagined as the circulatory conduits being in a state of internal constriction. This state reflects in the pulse as a Weak Xian pulse.

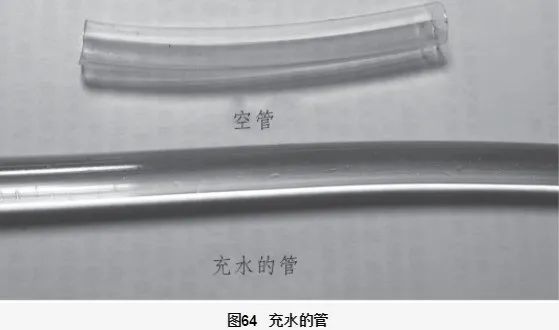

Due to emotional “stagnation,” the microcirculation between the conduits and tissues tightens, increasing conduit pressure. We can understand that the Weak Xian pulse, compared to the Qi Xian pulse, is caused by increased pressure at the input end of the conduits, while the Qi Xian pulse is caused by increased pressure at the output end. We represent the Weak Xian pulse as follows, with downward arrows and horizontal lines indicating input pressure on the conduits.

What is the tactile sensation of the Weak Xian pulse like?

This pulse type is relatively simple: it is a Xian pulse with weak qi. When the fingers touch the pulse, it feels straight; when pressing into the conduit, the qi felt is weak, without the forceful sensation of the Qi Xian pulse. When the pulse is dominated by the Weak Xian pulse, I usually prescribe Xiao Yao San.

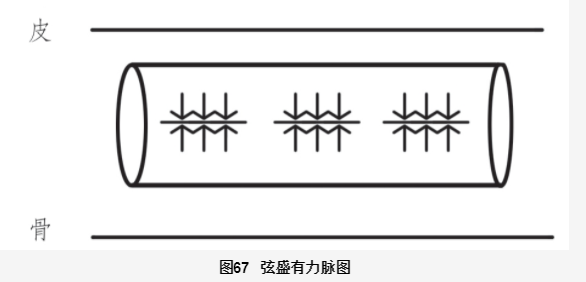

4. Xian Sheng You Li Mai (Strong Xian Pulse)

This pulse is characterized by a Xian shape with strong qi. Compared to the Qi Xian pulse, the Strong Xian pulse has even more strength. Unlike the Qi Xian pulse, which requires pressing to the middle of the pulse to feel the force, this pulse is forceful at floating, middle, and deep levels, belonging to the liver excess heat syndrome in organ differentiation, representing a progression and intensification of the Qi Xian pulse, indicating extreme qi stagnation and heat.

The Strong Xian pulse is illustrated as follows:

We will use a case to illustrate the clinical application of this pulse type.

Patient: Male, 32 years old. Presenting with “sudden pain and foreign body sensation in the right eye.”

On examination, a block-like hemorrhage was observed on the inner conjunctiva of the right eye, with symptoms of bitter mouth and irritability, and yellow urine. Both guan pulses were Xian and large, with a strong forceful sensation, while other pulse positions were thin. The left cun pulse was thin and not smooth, while the right guan was large and forceful, indicating internal liver fire. The strong liver fire travels along the meridian and naturally spills out from the weak points of the liver and gallbladder meridians, leading to conjunctival hemorrhage. The conjunctiva, being a weak blood vessel, is the first to be affected, sacrificing itself to protect other areas. Conjunctival hemorrhage is certainly preferable to intracranial hemorrhage. The prescription was based on Long Dan Xie Gan Tang (Gentiana Decoction to Drain the Liver), addressing the significant contradiction of excessive wood and fire. Other adjustments were merely minor techniques, not critical.

The prescription was as follows: He Shou Wu 20g, Bai Zhi 12g, Ma Huang 3g, Sang Ye 10g, Da Huang 10g, Yi Mu Cao 20g, Long Dan Cao 3g, Shan Zhi Zi 10g, Che Qian Zi 15g, Mu Tong 10g, Huang Qin 10g, Gui Zhi 3g, Dang Gui 10g, Sheng Di Huang 15g, Ze Xie 15g, Sheng Gan Cao 10g, Chai Hu 15g.

3 doses.

After 2 days, follow-up revealed improvement in all symptoms, and the hemorrhagic spots had begun to resolve.

5. Xian Kang Mai (Hyperactive Xian Pulse)

The Hyperactive Xian pulse is a very special pulse type in clinical practice. What is this pulse type like?

As illustrated, this pulse type is characterized by increasing strength as it is taken in the floating position. When lightly touching the pulse skin, one can feel a strong and vigorous sensation, but as the finger continues to press down, this strong sensation gradually weakens, becoming weaker until it feels weak and powerless at the bottom. This pulse type is what we commonly refer to as the Hyperactive Xian pulse. Because this pulse type involves a comparison of floating and sinking, it cannot be explained using the conduit model.

What does this pulse type reflect in terms of pathogenesis?

This pulse type is usually large, “a large pulse indicates exhaustion”, reflecting a side of deficiency and insufficiency; the floating pulse is strong, while the sinking pulse is weak, reflecting a side of internal deficiency and floating yang qi; the floating Xian pulse indicates a side of stagnation.

From the perspective of organ differentiation, this pulse type indicates “excessive liver wood dispersion”. The underlying cause is still due to insufficient jin ye in the interior, leading to inadequate nourishment of the blood, causing the liver wood to become dry. Once the liver wood becomes dry, it will fail to perform its dispersing function. Due to deficiency heat, there is excessive qi dispersion, while dryness leads to insufficient expansion, resulting in this special Hyperactive Xian pulse.

The treatment for this syndrome, in addition to selecting prescriptions based on specific symptoms and signs, is crucially to supplement the jin ye in the interior. As long as the jin ye in the interior is replenished, deficiency heat can be pacified, liver qi can be soothed, and symptoms can be alleviated. Common formulas for replenishing jin ye in the interior include Shen Qi Wan, Liang Wei Di Huang Wan, and Wu Zi Yan Zong Wan.

In clinical practice, some emotionally volatile patients have shown improvement in symptoms and even their temper after using Shen Qi Wan combined with Wu Zi Yan Zong Wan.

We will use a case to illustrate the clinical application of this pulse type.

Patient: Female, 60 years old.

Presenting with “pulling pain along the back of the lower limbs.”

The patient experiences pulling pain from the heels to the lower back, which is more pronounced when standing and alleviated when lying down. Resting helps relieve the pain, and sleep and bowel movements are normal. Pulse diagnosis reveals both guan pulses are Hyperactive Xian, while both chi pulses are thin. This indicates insufficient jin ye, leading to inadequate nourishment of the tendons, resulting in pulling pain, specifically in the heels extending to the waist and legs.

The patient has a good appetite, and her spleen and stomach digestive functions are satisfactory.

Therefore, I directly used Liang Wei Di Huang Wan to replenish jin ye and Shaoyao Gan Cao Tang to drain liver qi. The Huang Di Nei Jing states: “The liver desires dispersion… consume pungent foods to supplement it, consume sour foods to drain it.” Thus, the sour and bitter properties of Shaoyao can drain excessive liver wood qi, while Gan Cao can alleviate its urgency. Adding Su Zao Ren can nourish the liver, and Jin Ling Zi San can clear liver heat.

The specific prescription is as follows:

Gou Qi Zi 20g, Chuan Niu Xi 15g, Sheng Di Huang 30g, Huai Shan Yao 30g, Shan Zhu Yu 24g, Mu Dan Pi 10g, Ze Xie 10g, Fu Ling 20g, Bai Shao 24g, Zhi Gan Cao 10g, Su Zao Ren 12g, Rou Cong Rong 8g, Chuan Lian Zi 8g, Xuan Hu Suo 8g.

Two doses.

During the second diagnosis, the patient reported that the pulling pain in the heels had mostly resolved, with only slight pain remaining after walking. The pulse diagnosis showed a reduction in the Hyperactive Xian pulse in the right guan, while the left guan appeared slightly weaker.

The weakness in the right guan reflects a pre-existing spleen deficiency. Following the principle in the Jin Gui Yao Lue: “When observing liver disease, recognize its transmission to the spleen, and first strengthen the spleen,” I added Li Zhong Tang to the original formula to replenish the earth qi, allowing the nourishing qi to naturally arise. As the liver qi decreases, I removed Jin Ling Zi San, as its cold draining properties are not suitable for spleen and kidney deficiencies.

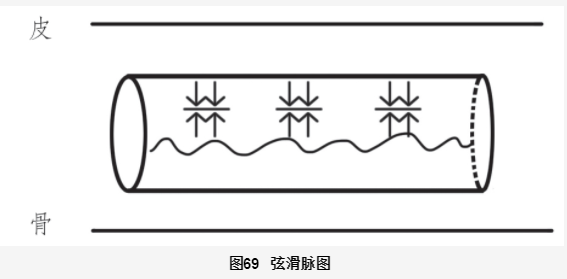

6. Xian Hua Mai (Slippery Xian Pulse)

The Slippery Xian pulse is often seen in cases of phlegm-qi stagnation.

We will use a case to illustrate this pulse type.

A woman in her 50s presented with numbness and discomfort in both lower limbs below the knees. Pulse diagnosis revealed both hands had a rough and obstructed pulse, with a pale and slightly dark tongue. This indicates insufficient qi and blood, combined with qi stagnation and blood stasis. The treatment used Zhang Xichun’s Xiao Ling Huo Luo Dan combined with Huang Qi Gui Zhi Wu Wu Tang and Si Ni San.

The prescription is as follows: Dan Shen 15g, Dang Gui 12g, Ru Xiang 5g, Huang Qi 20g, Gui Zhi 12g, Bai Shao 12g, Da Zao 10g, Sheng Jiang 10g, Chuan Niu Xi 15g, Ji Xue Teng 15g, Xi Xin 2g, Fo Shou 10g, Chai Hu 12g, Zhi Ke 12g, Xiang Fu 10g, Dai Dai Hua 10g, Chen Pi 10g, Mei Yao 10g, Mo Yao 5g, Di Long 10g.

5 doses.

During the second diagnosis, the patient reported that after taking 2 doses, the numbness in her feet had resolved, but she experienced pain in the left knee. When asked when the pain started, she mentioned it had been ongoing for a long time but was ignored due to the severe numbness. Now she hoped to treat the knee pain as well. Upon pulse diagnosis, it was found that the pulse had changed compared to before. The left hand pulse remained thin, indicating blood deficiency, while the right guan pulse appeared Slippery Xian.

This Slippery Xian pulse indicates that the pulse skin feels Xian, but when pressing into the conduit, the qi feels smooth and flowing like beads, as illustrated:

The left hand pulse being thin suggests blood deficiency, while the knee, being the residence of the tendons, lacks nourishment due to blood deficiency. The right guan pulse being Slippery indicates phlegm turbidity obstructing the conduits, leading to qi stagnation, hence the knee pain. The treatment used Si Wu Tang combined with Huang Qi Gui Zhi Wu Wu Tang and Dan Shen, Ji Xue Teng to nourish blood and unblock the conduits, and Fu Ling Yin to eliminate middle jiao phlegm turbidity. The specific prescription is as follows:

Dan Shen 15g, Dang Gui 15g, Huang Qi 20g, Gui Zhi 10g, Bai Shao 20g, Da Zao 10g, Sheng Jiang 10g, Ji Xue Teng 15g, Dang Shen 15g, Bai Zhu 15g, Fu Ling 15g, Zhi Shi 12g, Xing Ren 15g, Ban Xia 10g, Zhi Gan Cao 6g, Sheng Di Huang 20g, Mu Guo 15g, Chuan Xiong 12g.

5 doses.

After 4 days of follow-up, the patient reported that the knee pain had resolved. This case indicates that the local Slippery Xian pulse reflects phlegm turbidity obstructing the conduits, leading to qi stagnation. Why use Fu Ling Yin for the Slippery Xian pulse instead of Er Chen Tang? If it were a simple Slippery pulse, Er Chen Tang would certainly be appropriate. However, since the Slippery Xian pulse involves the Xian pulse, it indicates the presence of qi stagnation and water retention. Therefore, the Fu Ling Yin formula, which includes Fu Ling and Bai Zhu, targets this water retention, while Zhi Shi in Fu Ling Yin addresses the qi stagnation, making it more suitable than Er Chen Tang.

7. Xian Kang and Hua Mai (Hyperactive and Slippery Xian Pulse)

This pulse type corresponds to a syndrome of liver wind combined with phlegm, which is also commonly seen in clinical practice. Let’s illustrate this with a case.

A 60-year-old female patient presented with dizziness for 2 weeks, with symptoms triggered by turning in bed, standing up, or lying down, accompanied by a sensation of spinning, excessive sweating, no palpitations, no dry mouth or bitter taste, no headache, no sensitivity to wind or cold, and severe insomnia. Her appetite was normal, and her bowel and urination were regular. Pulse diagnosis revealed an overall Hyperactive and Slippery Xian pulse, with a white and slightly thick tongue coating.

This pulse type exhibits a straight sensation on the pulse skin, with a slippery and forceful feeling at the surface, while the qi becomes weaker as one presses deeper, and the slippery sensation is only present at the surface of the pulse. This indicates that the forceful and slippery sensations at the surface of the pulse are related to the weakening of the pulse as it goes deeper. This hyperactive qi and phlegm are both due to internal deficiency. Based on the pulse analysis, the prescription is as follows:

Sheng Ban Xia 20g, Bai Zhu 45g, Tian Ma 15g, Chen Pi 15g, Ze Xie 60g, Mu Li 30g, E Jiao 10g, Fu Ling 60g, Sheng Jiang 20g, Qian Shi 30g, Shen Fu 15g, Bai Shao 25g.

3 doses.

The formula uses Ban Xia Bai Zhu Tian Ma Tang to eliminate the floating wind phlegm, while Zhang Xichun’s phlegm formula addresses the internal phlegm syndrome, and Zhen Wu Tang targets the water syndrome caused by internal deficiency. E Jiao can quickly replenish the jin ye in the interior. Often, E Jiao is also an excellent remedy for phlegm.

After taking the medication, the patient was able to sleep, and the dizziness during sleep and turning was alleviated, with only slight dizziness occurring when looking down or lifting her head.

8. Xian Jin Mai (Tight Xian Pulse)

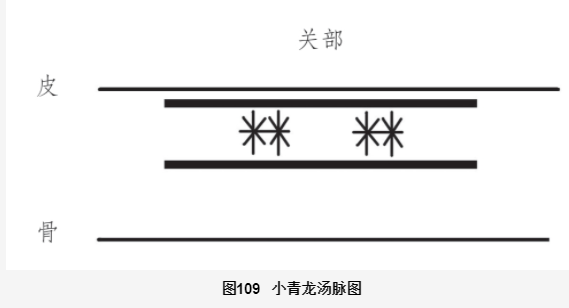

Tightness indicates cold, while Xian indicates water. Therefore, the Tight Xian pulse is a typical pulse type indicating a combination of cold and water. We will discuss this pulse type based on the Xiao Qing Long Tang pulse from the pulse chapter.

The Shang Han Lun states: “In cases of cold damage, if the exterior does not resolve, and there is water qi in the heart, with symptoms of dry heaving, fever, cough, thirst, diarrhea, or difficulty urinating, or fullness in the lower abdomen, or wheezing, Xiao Qing Long Tang is indicated.”

Xiao Qing Long Tang is used for conditions with external wind-cold and internal phlegm-water. Clinically, the opportunity to use Xiao Qing Long Tang for cough and wheezing is quite common. The characteristics of this cough and wheezing include white, foamy sputum, worsening symptoms after rain or swimming, and a preference for air conditioning and cold drinks, as well as a fondness for meat, but the most distinctive feature is the pulse type.

The pulse of Xiao Qing Long Tang is one of the most characteristic and easily recognizable pulse types. Whenever this pulse is observed, using this formula will yield good results. We will illustrate the characteristics of this pulse type with a case.

Patient: 8 years old, presenting with recurrent cough, having undergone multiple treatments with no improvement.

Previous doctors prescribed cough suppressants with modifications twice, but the cough did not improve. Currently, the patient has a cough, with a white, thick tongue coating, and pulse diagnosis reveals both guan pulses are floating, Xian, and tight.

This is a typical Xiao Qing Long Tang pulse. Due to the thick white tongue coating, some digestive herbs were added to the prescription, which is as follows:

Bai Shao 15g, Gan Jiang 8g, Wu Wei Zi 6g, Ma Huang 6g, Zhi Gan Cao 6g, Xi Xin 3g, Ban Xia 10g, Gui Zhi 10g, Shi Gao 15g, Shen Qu 10g, Mai Ya 10g, Shan Zhi 10g, Ji Shi Teng 20g, Chen Pi 6g, Cang Zhu 10g.

3 doses.

The patient’s mother reported that after taking just one dose, the cough significantly reduced and was nearly resolved.

In clinical practice, whenever both hands exhibit floating, Xian, and tight pulses, regardless of whether it is a cough or other symptoms, I always use Xiao Qing Long Tang with modifications for treatment. Of course, if the pulse is not accurately assessed and does not exhibit floating, Xian, and tight characteristics, the effectiveness of Xiao Qing Long Tang will be poor.

I once treated a stubborn cough patient whose pulse was floating, Xian, and tight, but the pulse qi was weak. The cun pulse was insufficient, so I used Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Ren Shen and a large dose of Huang Qi for effectiveness. I also treated a cough patient whose pulse was floating, Xian, and tight, but the right cun pulse was floating, tight, and slippery, using Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Ma Xing Shi Gan Tang for effectiveness. I treated a patient with abdominal distension and pain who had sought treatment for many years with no effect; both hands exhibited floating, Xian, and long pulses, so I used Xiao Jian Zhong Tang with increased dosages of Gui Zhi and Bai Shao, making repeated adjustments until I replenished kidney essence and achieved a cure. I also treated a chronic rhinitis patient whose pulses were floating, Xian, and tight in both guan and chi positions, while the cun pulses were weak, using Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Bushi Zhong Yi Qi Tang to achieve good results.

This article is excerpted from Illustrated Pulse Diagnosis, copyright belongs to the relevant rights holder. Sharing this article is for the purpose of dissemination and learning exchange. If there are any improper uses, please feel free to contact us for removal.