The Xian Mai (Xian Pulse) is the most common and representative pulse type in clinical practice, characterized by its variability. It resembles a taut string, indicating tension, tightness, and a lack of softness and fluctuation. It can be seen in conditions of dryness and lack of nourishment, as well as in states of contraction and rigidity. Both cold and heat can present with a Xian pulse, as can conditions of liver and kidney yin deficiency and phlegm retention. How can we understand the Xian pulse using a conduit model?

Imagine a hollow, soft rubber tube. When inflated, it becomes taut, similar to the formation of a Xian pulse.

The Xian pulse arises from increased pressure within the conduit, causing a blockage in the exchange between the conduit and surrounding tissues. For instance, when a person’s emotions change, such as during anger, the pressure within the conduit can suddenly increase, leading to a Xian pulse. During states of tension and repression, nerve reflexes cause both the ends of the conduit and the tissues to tighten, further increasing pressure and making the Xian pulse more pronounced. In modern society, as people experience increasing stress, the Xian pulse has become more prevalent.

However, the formation of the Xian pulse is not solely related to emotions. Next, we will analyze different types of Xian pulses.

1. Zheng Xian Mai (Normal Xian Pulse)

This is the most clinically significant pulse type.

Before discussing the Zheng Xian pulse, we must introduce two important concepts: Fluid Balance and Blood-Fluid Exchange Balance.

(1) Fluid Balance

Life originated in seawater, evolving from single-celled organisms into complex life forms. Every cell and tissue must survive on the nourishment of water. The human body is no exception; all metabolic processes rely on water as a medium, highlighting its dominant role in the body.

What nourishes can also harm. Water is the fundamental fluid for life and is also a significant factor in the development of diseases.

For every cell and tissue, both too little and too much water are detrimental. The body’s ability to accommodate water is related to the current state of its yang qi. When the yang qi of the body’s tissues and cells is in a balanced state with water, the fluid can be transformed into jin ye (body fluids) for utilization. We can refer to this state as the Fluid Balance state.

If there is too much fluid, exceeding the burden of yang qi, the excess will become waste, referred to as “yin” evil. This waste cannot be utilized and will accumulate in various layers and parts of the body, leading to various diseases.

Many people may not believe that numerous diseases arise from excessive water intake or incorrect drinking methods (e.g., drinking large amounts of water when thirsty). Recently, I treated a patient with severe palpitations and premature beats. According to his description, the onset was due to drinking large amounts of water after discovering he had kidney stones. Although the stones were expelled, he developed heart disease and required radiofrequency ablation treatment, along with daily medication, which did not effectively control his symptoms. I prescribed a formula based on Ling Gui Zhu Gan Tang (Poria, Cinnamon, Atractylodes, and Licorice Decoction), and through herbal treatment, his symptoms were controlled, allowing for a gradual reduction in Western medication.

(2) Blood-Fluid Exchange Balance

Here, the term “blood” does not equate to the Western medical concept of blood. Instead, it refers to the jin ye within. We can understand it as follows: water, under the influence of yang qi, carries various energy nutrients to become jin ye, which nourishes the exterior as qi and the interior as blood. After completing its nourishing task, jin ye will exit from the blood. The Blood-Fluid Exchange Balance refers to a state where the flow of fluids in and out of the interior is balanced and smooth. When the flow of jin ye becomes stagnant, leading to the formation of stasis blood, the entry of water into the interior will be obstructed, disrupting this balance.

Stasis blood syndrome can lead to obstruction of jin ye entering the blood, which is why many stasis blood syndromes are accompanied by symptoms of dryness and heat, such as irritability, dry lips, and yellow urine. Clinically, we often see patients with signs of deficiency and cold, yet they also exhibit obvious symptoms of dryness and heat. This is because, on one hand, the deficiency of yang qi fails to vaporize jin ye, leading to insufficient jin ye; on the other hand, due to the presence of stasis blood, the entry of jin ye into the blood is obstructed, resulting in further insufficiency of nourishment to the blood. This leads to the simultaneous presence of deficiency and cold, along with dryness and heat.

Based on my clinical experience, I believe there are three key junctions for blood-fluid exchange in the body, located in the upper, middle, and lower jiao. When stasis blood syndrome is severe and occurs at these junctions, the concept of blood-fluid exchange becomes particularly important.

In the upper jiao, blood stasis and fluid reflux can lead to excessive sweating, primarily in the upper body, worsening with tension. When jin ye fails to nourish the blood, it can result in insomnia and vivid dreams, treated with Xue Fu Zhu Yu Tang (Blood Mansion Decoction).

In the middle jiao, blood stasis and fluid reflux can lead to diarrhea, which is why Wang Qingren used his Ge Xia Zhu Yu Tang to treat chronic diarrhea and early morning diarrhea. Zhang Zhongjing’s Shang Han Lun mentions using Huang Qin Tang for diarrhea: “When Tai Yang and Shao Yang are combined, if there is diarrhea, use Huang Qin Tang; if there is vomiting, add Ban Xia and Sheng Jiang to the Huang Qin Tang to treat it.” This is due to stasis blood and heat causing diarrhea. From this perspective, we can understand what is meant by “heat binding and flowing sideways,” why heat binding flows sideways, and why we use Da Cheng Qi Tang to treat it.

In the lower jiao, blood stasis can lead to bladder blood retention, with fluid reflux into the bladder causing symptoms such as lower abdominal distension, frequent urination, and dry stools, treated with Tao Ren Cheng Qi Tang or Shao Fu Zhu Yu Tang. Once we understand the concepts of Fluid Balance and Blood-Fluid Exchange Balance, we can see that the entire Shang Han Lun discusses how to regulate these two core issues.

The Shang Han Lun provides a qualitative description of the Xian pulse.

In the Jin Gui Yao Lue regarding phlegm, cough, pulse diagnosis, and treatment, it states: “A double Xian pulse indicates cold. A偏 Xian pulse indicates fluid. A沉而弦 pulse indicates internal pain from suspended fluid.” This indicates that the Xian pulse is associated with water and fluid as the pathogenic factor.

This type of Xian pulse caused by fluid as a disease is what I refer to as the Zheng Xian Mai. How can we understand the Zheng Xian pulse from the conduit model?

The main pathways for water in the body are through the skin and urine. When the drainage functions of these two systems are impaired, the concentration of water in the cells increases. The main source of water in the body is through diet; improper eating habits, sudden excessive water intake, or frequent consumption of fruits can also increase the concentration of water in the cells. An increased concentration of water in the cells will lead to increased permeability in the conduits, ultimately resulting in overload and the formation of yin evil. This yin evil trapped in the conduits will lead to increased pressure, even affecting normal exchanges between the conduits and cells, which is the mechanism of formation and pathology of the Zheng Xian pulse.

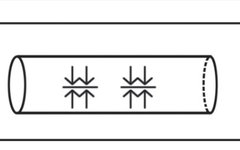

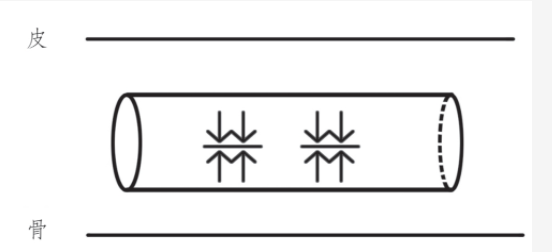

We represent the pulse diagram of the Zheng Xian pulse (63) as follows:

The diagram of the Zheng Xian pulse reflects increased tension in the conduits, with exchanges in and out being obstructed.

If the image is insufficient to fully describe the specific form of the Zheng Xian pulse, what should the tactile sensation be like?

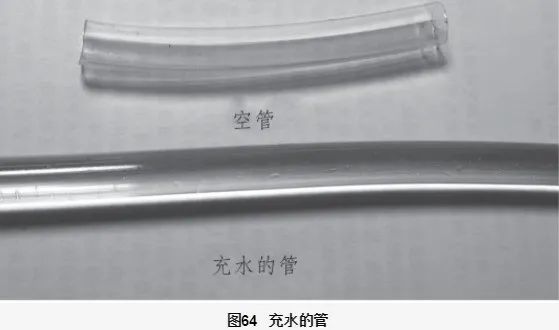

The Zheng Xian pulse should have the following characteristics: when the hand is placed on the pulse skin, the pulse shape exhibits a straight and long characteristic; when pressing inward towards the conduit, there is no slippery sensation, no weakness, no diminishing sensation, and no sensation of qi pushing against the fingertips. Instead, there is a feeling of fullness within the conduit, but it does not feel as tight and lacking in elasticity as a solid pulse. The specific sensation is akin to a conduit filled with water. Describing it in words may still be difficult to grasp. We can imagine that a typical pulse resembles an empty tube, while the Zheng Xian pulse resembles a water-filled tube that has a certain pressure, as shown in Figure 64.

When the Zheng Xian pulse is present, patients often experience symptoms such as chest tightness and cough related to lung fluid conditions;

When the left cun exhibits a Zheng Xian pulse alone, patients often experience palpitations and heart discomfort related to heart fluid conditions;

When both cun pulses exhibit a Zheng Xian pulse, patients may experience symptoms such as shortness of breath, upward qi counterflow, cough, a sensation of a foreign body in the throat, and swallowing obstruction related to fluid obstruction in the upper jiao. The treatment for upper jiao fluid conditions is with Ling Gui Zhu Gan Tang. This formula, while composed of balanced herbs, is a treasure for elderly health, as it can clear upper jiao fluid, significantly reducing the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

Middle Jiao fluid conditions typically present with a Zheng Xian pulse at the guan pulse. If the Zheng Xian pulse appears at the right guan, it usually indicates symptoms such as abdominal distension, borborygmi, diarrhea, and belching related to gastrointestinal fluid conditions, treated with Sheng Jiang Xie Xin Tang or Shen Zha Tang. If the Zheng Xian pulse appears at the left guan, it usually indicates symptoms such as poor appetite, bitter mouth, and chest and flank distension, treated with Chai Hu formulas.

Lower Jiao fluid conditions typically present with a Zheng Xian pulse at the chi pulse, often accompanied by symptoms such as abnormal urination, low back pain, cold feet, cold lower back, cold buttocks, dizziness, and a heavy head, treated with Wu Ling San, Zhen Wu Tang, or Fu Zi Tang.

Clinical practice has shown that patients exhibiting Zheng Xian pulses in multiple locations often eventually present with a weak pulse at the right guan after treatment, necessitating a conclusion with formulas like Li Zhong Tang, which fully demonstrates that fluid is generated by the spleen and stomach. One cannot live without water, but one can also be harmed by it. The above discussion pertains to the situation where a Zheng Xian pulse appears in a single location while other areas are generally normal. Clinical applications must also be analyzed based on specific circumstances.

2. Qi Xian Mai (Qi Xian Pulse)

The general discussion of the Xian pulse mentioned that when a person is in a state of anger without expression, the pressure in the conduits increases, and the exchange is obstructed by “qi,” leading to the appearance of the Xian pulse. We can borrow the term from the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing to refer to this state of “qi blockage” as “Jie Qi”, and we call the Xian pulse in this state the Qi Xian Mai.

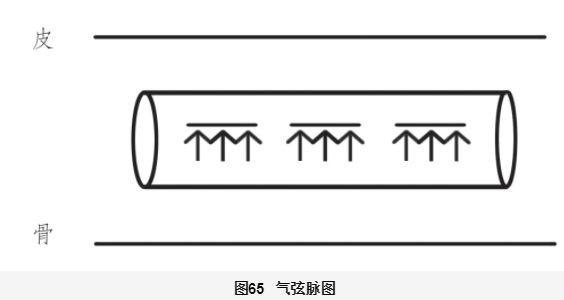

We can imagine a person in a state of rage, with blood vessels dilating and veins bulging, corresponding to an increased pressure state within the circulatory conduits. The diagram of the Qi Xian pulse is represented as follows: as shown in Figure 65, we use two arrows to indicate that the pulse qi force is at a normal level, while the three arrows in the diagram indicate that the pulse qi is excessive, with a strong sensation upon pressing, and the horizontal line on the arrows indicates that the pressure within the conduits is not smoothly released.

What is the tactile sensation of the Qi Xian pulse like?

When we press our fingers on the pulse skin, we feel the straight and long sensation of the Xian pulse. When pressing inward towards the pulse, the sensation of pulse qi is strong but not slippery, not properly Xian, and not solid. When pressing towards the center of the conduit, we feel a force pushing our fingers away, similar to an angry person refusing to let someone close.

The Qi Xian pulse represents excessive and stagnant qi.

When the Qi Xian pulse appears at the floating position, we can use some floral and leaf qi-regulating herbs in combination for treatment, such as Zi Su Ye, Zi Su Gen, Ju Ye, Qing Pi, Chen Pi, Bo He, and Hua Jiao; when the Qi Xian pulse appears in the middle or deep position, we can choose to use Si Ni San for treatment.

Clinically, the Qi Xian pulse is often seen at the guan pulse, and it tends to be larger than at other locations.

3. Xian Ruo Mai (Weak Xian Pulse)

We have discussed the Qi Xian pulse characterized by excessive anger and qi. Correspondingly, there is a type of Xian pulse characterized by repression, tension, and weak qi, which we refer to as the Xian Ruo Mai.

There is often a type of patient whose constitution is weak, personality is gentle, and who frequently swallows their anger, holding it in. They are often in a state of tension and defense, which can be imagined as the circulatory conduits being in a state of internal contraction and tightness. This state reflects in the pulse as the Xian Ruo pulse.

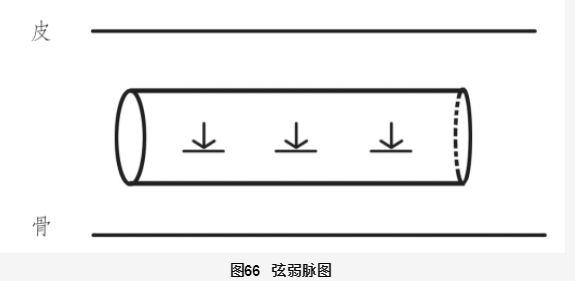

Due to emotional “stagnation,” the microcirculation between the conduits and tissues tightens, leading to increased pressure within the conduits. We can understand that the Xian Ruo pulse, compared to the Qi Xian pulse, is caused by increased pressure at the input end of the conduits, while the Qi Xian pulse is caused by increased pressure at the output end. We represent the Xian Ruo pulse in Figure 66, with downward arrows and horizontal lines indicating input pressure on the conduits.

What is the tactile sensation of the Xian Ruo pulse like?

This pulse type is relatively simple: it is a Xian pulse with weak qi. When the fingers touch the pulse, it feels straight, and when pressing inward, the sensation of pulse qi is weak, lacking the strong sensation of the Qi Xian pulse. When the pulse is dominated by the Xian Ruo pulse, I usually prescribe Xiao Yao San (Free and Easy Wanderer Powder).

4. Xian Sheng You Li Mai (Strong Xian Pulse)

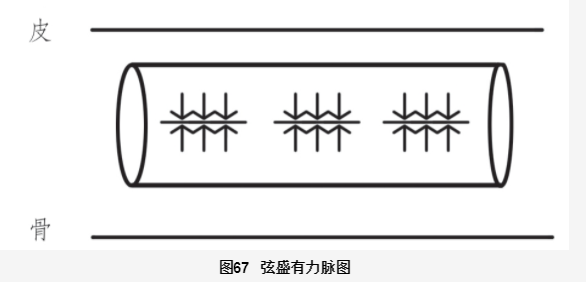

This pulse is characterized by a Xian shape with strong qi. Compared to the Qi Xian pulse, the Xian Sheng You Li pulse has even stronger qi. Unlike the Qi Xian pulse, where one must press to the middle of the pulse to feel the pressure, this pulse is strong at all levels, whether floating, middle, or deep. It belongs to the diagnosis of liver excess heat syndrome, representing a progression and intensification of the Qi Xian pulse, where qi stagnation leads to heat.

The Xian Sheng You Li pulse is illustrated in Figure 67.

We will use a case to illustrate the clinical application of this pulse type.

Patient: Male, 32 years old. Presenting with “sudden pain and foreign body sensation in the right eye.”

On examination, a block-like hemorrhage was observed on the inner conjunctiva of the right eye, with symptoms of bitter mouth and irritability, and yellow urine. Both guan pulses were Xian and large, with a strong sensation upon pressing, while other pulse areas were thin. The left cun pulse was thin and not smoothly Xian, while the right guan was large and strong, indicating internal liver fire. The strong liver fire travels along the meridian and naturally spills out from the weak points of the liver and gallbladder meridians, leading to conjunctival hemorrhage. The conjunctiva, being a weak blood vessel, is the first to be affected, sacrificing itself to ensure the safety of other areas. Conjunctival hemorrhage is certainly preferable to intracranial hemorrhage. The prescription was based on Long Dan Cao Xie Gan Tang (Gentiana Decoction to Drain the Liver), addressing the significant contradiction of excessive wood and fire. Other adjustments were minor and not critical.

The prescription was as follows: He Shou Wu 20g, Bai Ji Li 12g, Ma Huang 3g, Sang Ye 10g, Da Huang 10g, Yi Mu Cao 20g, Long Dan Cao 3g, Shan Zhi Zi 10g, Che Qian Zi 15g, Mu Tong 10g, Huang Qin 10g, Gui Zhi 3g, Dang Gui 10g, Sheng Di Huang 15g, Zea Xia 15g, Sheng Gan Cao 10g, Chai Hu 15g.

3 doses.

Two days later, follow-up by phone indicated improvement in all symptoms, with the hemorrhage resolving.

5. Xian Kang Mai (Hyperactive Xian Pulse)

The Xian Kang pulse is a very special pulse type in clinical practice. What is this pulse like?

As shown in Figure 68, this pulse type is characterized by an increasing strength of the pulse as it is taken at the floating level. When lightly touching the pulse skin, one can feel a strong and vigorous sensation, but as one continues to press down, this strong sensation gradually weakens, becoming weaker and weaker until it feels weak and powerless at the bottom. This pulse type is what we commonly refer to as the Xian Kang pulse. Because this pulse type involves a comparison of floating and sinking, it cannot be explained using the conduit model.

What does this pulse type reflect in terms of pathology?

This pulse type is usually large, with “large pulse indicates exhaustion”, reflecting a side of deficiency and insufficiency; the floating pulse is strong, while the sinking pulse is weak, reflecting a side of internal deficiency and floating yang qi; the floating pulse being Xian indicates a side of stagnation.

From the perspective of organ differentiation, this pulse type indicates “excessive liver wood dispersion.” The underlying reason is still due to insufficient jin ye in the interior, leading to inadequate nourishment of the blood. When the liver wood becomes dry, it fails to perform its dispersing function. Due to deficiency heat, there is excessive qi dispersion, while dryness leads to insufficient expansion, resulting in this special Xian Kang pulse.

From the perspective of the six meridians, this pulse type corresponds to the Shaoyang and Yangming diseases of deficiency syndrome, indicating a combination of deficiency syndrome with Shaoyang stagnation and dryness heat. Patients with this pulse type often experience irritability due to dryness, dry mouth, dry eyes, yellow urine, irritability, poor sleep, dry mucous membranes and skin, and dry red lower lips; on the other hand, they may also experience fear of wind and cold, with cold hands and feet. A weak constitution is prone to recurrent phlegm fluid conditions; qi stagnation is prone to recurrent Si Ni San syndrome; and blood deficiency and heat can easily lead to stasis blood syndrome over time. These characteristics lead to recurrent diseases, making treatment quite challenging.

The treatment for this condition, in addition to selecting prescriptions based on specific symptoms and signs, is crucially to supplement the jin ye in the interior. As long as the jin ye in the interior is replenished, deficiency heat can be pacified, and liver qi can be soothed, alleviating symptoms. Common formulas for replenishing jin ye include Shen Qi Wan, Liang Wei Di Huang Wan, and Wu Zi Yan Zong Wan.

In clinical practice, some emotionally volatile patients have shown significant improvement in symptoms and temperament after using Shen Qi Wan combined with Wu Zi Yan Zong Wan.

We will use a case to illustrate the clinical application of this pulse type.

Patient: Female, 60 years old.

Presenting with “pulling pain along the back of the lower limbs.”

The patient experiences pulling pain from the heels to the lower back, which is more pronounced when standing and alleviated when lying down. Resting helps relieve the pain, and sleep and bowel movements are normal. Upon pulse diagnosis, both guan pulses are Xian Kang, while both chi pulses are thin. This indicates insufficient jin ye, leading to inadequate nourishment of the tendons, resulting in pulling pain, specifically in the heels extending to the waist and legs.

The patient has a good appetite, and her spleen and stomach digestive functions are satisfactory.

Therefore, I directly used Liang Wei Di Huang Wan to replenish jin ye and Shaoyao Gan Cao Tang to drain liver qi. The Huang Di Nei Jing states: “The liver desires to disperse… eat pungent to supplement it, eat sour to drain it.” Therefore, the sour and bitter properties of Shaoyao can drain excessive liver wood qi, while Gan Cao can alleviate its urgency, and Jinzhenzi can nourish the liver.

The specific prescription is as follows:

Gou Qi Zi 20g, Chuan Niu Xi 15g, Sheng Di Huang 30g, Huang Shan Yao 30g, Shan Zhu Yu 24g, Mu Dan Pi 10g, Zea Xia 10g, Fu Ling 20g, Bai Shao 24g, Zhi Gan Cao 10g, Suan Zao Ren 12g, Rou Cong Rong 8g, Chuan Lian Zi 8g, Xuan Hu Suo 8g.

3 doses.

During the second consultation, the patient reported that the pulling pain in the heels had mostly resolved, with only slight pain remaining after walking. Upon pulse diagnosis, the Xian Kang pulse at the right guan had diminished, while the left guan appeared slightly weaker.

The weakness of the right guan pulse reflects a constitution prone to spleen deficiency. Following the principle in the Jin Gui Yao Lue that states, “When seeing liver disease, know that it transmits to the spleen, and one must first strengthen the spleen,” I added Li Zhong Tang to the original formula to replenish the earth qi, allowing the nourishing qi to naturally arise, reducing liver qi. I removed Jinzhenzi from the formula, as its cold draining properties are not suitable for spleen and kidney deficiency.

6. Xian Hua Mai (Slippery Xian Pulse)

The Xian Hua pulse is often seen in cases of phlegm qi stagnation.

We will use a case to illustrate this pulse type.

A woman in her 50s presented with numbness and discomfort in both lower limbs below the knees. Upon pulse diagnosis, both hands exhibited a rough and obstructed pulse, with a pale and slightly dark tongue. This indicates insufficient qi and blood, along with qi stagnation and blood stasis. The treatment involved using Zhang Xichun’s Xiao Ling Huo Luo Dan combined with Huang Qi Gui Zhi Wu Wu Tang and Si Ni San.

The prescription is as follows: Dan Shen 15g, Dang Gui 12g, Ru Xiang 5g, Huang Qi 20g, Gui Zhi 12g, Bai Shao 12g, Da Zao 10g, Sheng Jiang 10g, Chuan Niu Xi 15g, Ji Xue Teng 15g, Xi Xin 2g, Fo Shou 10g, Chai Hu 12g, Zhi Ke 12g, Xiang Fu 10g, Da Huang 10g.

5 doses.

During the second consultation, the patient reported that after taking 2 doses, the numbness in her feet had resolved, but she experienced pain in the left knee. When asked when the pain started, she mentioned it had been ongoing for a long time but had been ignored due to the numbness. Now she hoped to treat the knee pain as well. Upon pulse diagnosis, the pulse had changed compared to before. The left hand pulse remained thin, indicating blood deficiency, while the right guan pulse appeared Xian Hua.

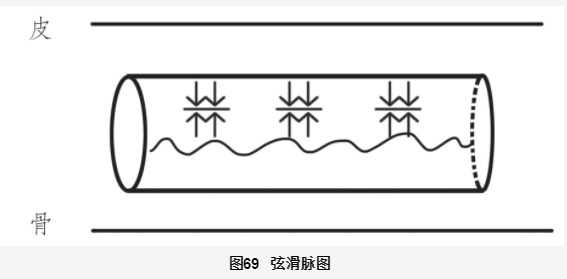

This Xian Hua pulse is characterized by a pulse that feels Xian upon pressing but is slippery and smooth when pressing deeper into the conduit, as illustrated in Figure 69.

The left hand pulse being thin suggests blood deficiency, while the right guan pulse being Xian Hua indicates phlegm obstruction, leading to qi stagnation and thus knee pain. The treatment involved using Si Wu Tang combined with Huang Qi Gui Zhi Wu Wu Tang to nourish blood and unblock the meridians, along with Fu Ling Yin to eliminate phlegm and turbidity from the middle jiao. The specific prescription is as follows:

Dan Shen 15g, Dang Gui 15g, Huang Qi 20g, Gui Zhi 10g, Bai Shao 20g, Da Zao 10g, Sheng Jiang 10g, Ji Xue Teng 15g, Dang Shen 15g, Bai Zhu 15g, Fu Ling 15g, Zhi Ke 12g, Xing Ren 15g, Ban Xia 10g, Zhi Gan Cao 6g, Sheng Di Huang 20g, Mu Guo 15g.

5 doses.

After four days of follow-up, the patient reported that the knee pain had resolved.

This case indicates that the local Xian Hua pulse reflects phlegm obstruction, leading to qi stagnation. Why did we use Fu Ling Yin for the Xian Hua pulse instead of Er Chen Tang? If it were a simple slippery pulse, Er Chen Tang would certainly be appropriate. However, since the Xian Hua pulse involves both Xian and slippery characteristics, it indicates the presence of qi stagnation and water retention. Therefore, the ingredients in Fu Ling Yin, such as Fu Ling and Bai Zhu, target this water retention, while Zhi Ke in Fu Ling Yin addresses the qi stagnation, making it more suitable than Er Chen Tang.

7. Xian Kang and Hua Mai (Hyperactive and Slippery Xian Pulse)

This pulse type corresponds to a syndrome of liver wind with phlegm, which is also commonly seen in clinical practice. Let’s illustrate this with a case.

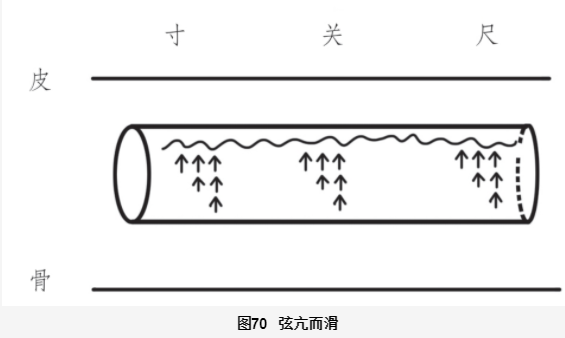

A 60-year-old female patient presented with dizziness for 2 weeks, with symptoms triggered by turning in bed, standing up, or lying down, accompanied by a sensation of spinning, excessive sweating, no palpitations, no dry mouth, no headache, no fear of wind or cold, no irritability, and severe insomnia. Her appetite was good, and her bowel movements were normal. Upon pulse diagnosis, the overall pulse was Xian Kang and slippery, with a thick white tongue coating, as shown in Figure 70.

This pulse type exhibits a straight sensation on the pulse skin, with a slippery and strong feeling at the surface, while the pulse becomes weaker as it sinks deeper, with the slippery sensation only present at the surface. This indicates that the strong and slippery sensation at the surface is related to the weakening of the pulse as it sinks deeper. This hyperactive qi and phlegm are both due to internal deficiency. Based on the pulse analysis, the prescription is as follows:

Sheng Ban Xia 20g, Bai Zhu 45g, Tian Ma 15g, Chen Pi 15g, Zea Xia 60g, Mu Li 30g, Ejiao 10g, Fu Ling 60g, Sheng Jiang 20g, Qian Shi 30g, Shu Fu 15g, Bai Shao 25g.

3 doses.

The formula uses Ban Xia Bai Zhu Tian Ma Tang to eliminate the floating wind phlegm, while Zhang Xichun’s phlegm treatment formula addresses the internal deficiency phlegm syndrome, and Zhen Wu Tang targets the water syndrome caused by internal deficiency, with Ejiao quickly replenishing the jin ye in the interior. Often, Ejiao is also an excellent remedy for phlegm.

After taking the medicine, the patient was able to sleep, and the dizziness during sleep and turning was alleviated, with only slight dizziness occurring when looking down or lifting the head.

8. Xian Jin Mai (Tight Xian Pulse)

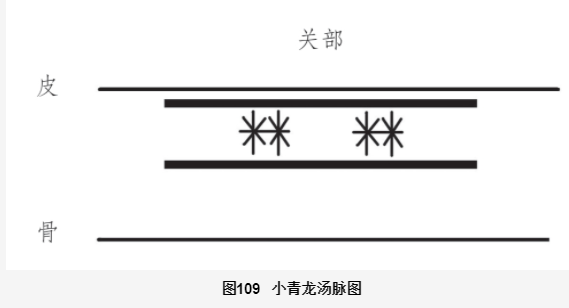

Tightness indicates cold, while Xian indicates fluid. Therefore, the Xian Jin pulse is a typical pulse type indicating a combination of cold and fluid. We will discuss this pulse type based on the Xiao Qing Long Tang pulse from the pulse chapter.

The Shang Han Lun states: “In cases of cold damage, if the exterior does not resolve, and there is water qi in the heart, with dry vomiting, fever, or thirst, or diarrhea, or difficulty urinating, or fullness in the lower abdomen, or wheezing, Xiao Qing Long Tang is indicated.”

Xiao Qing Long Tang is used for conditions with external wind-cold and internal phlegm fluid. In clinical practice, the opportunity to use Xiao Qing Long Tang for cough and wheezing is quite common. The characteristics of this cough and wheezing are that the phlegm is white and foamy, worsening after exposure to rain or swimming. The patient typically enjoys air conditioning, cold drinks, and meat, but the most characteristic aspect is the pulse type.

The pulse of Xiao Qing Long Tang is one of the most distinctive and easily recognizable pulse types. Whenever this pulse is observed, using this formula will yield good results. We will illustrate the characteristics of this pulse type with a case.

Patient: 8 years old, presenting with recurrent cough, having undergone multiple treatments with no improvement.

Previous doctors prescribed cough suppressants with no effect. The patient currently has a cough, with a thick white tongue coating, and upon pulse diagnosis, both guan pulses are floating, Xian, and tight.

This is a typical Xiao Qing Long Tang pulse. Due to the thick white tongue coating, I added some digestive herbs to the prescription, which is as follows:

Bai Shao 15g, Gan Jiang 8g, Wu Wei Zi 6g, Ma Huang 6g, Zhi Gan Cao 6g, Xi Xin 3g, Ban Xia 10g, Gui Zhi 10g, Shi Gao 15g, Shen Qu 10g, Mai Ya 10g, Shan Zha 10g, Ji Shi Teng 20g, Chen Pi 6g, Cang Zhu 10g.

3 doses.

The patient’s mother reported that after taking just one dose, the cough significantly reduced, nearing recovery.

In clinical practice, whenever both hands exhibit a floating, Xian, and tight pulse, regardless of whether it is a cough or other symptoms, I always use Xiao Qing Long Tang with adjustments for treatment. Of course, if the pulse is not accurately identified as floating, Xian, and tight, the effect of Xiao Qing Long Tang will not be good.

We have treated a stubborn cough patient with a pulse that was floating, Xian, and tight, but with weak qi at the寸 pulse. We used Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Ren Shen and a large dose of Huang Qi for effect; we treated a cough patient with a pulse that was floating, Xian, and tight, but with the right寸 pulse being floating, tight, and slippery, using Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Ma Xing Shi Gan Tang for effect; we treated a patient with abdominal distension and pain who had sought treatment for many years with no effect, with both hands exhibiting a floating, Xian, and tight pulse, using Xiao Jian Zhong Tang with increased doses of Gui Zhi and Bai Shao, with repeated adjustments, ultimately nourishing kidney essence and achieving a cure; we treated a chronic rhinitis patient with both guan and chi pulses being floating, Xian, and tight, and both寸 pulses being weak, using Xiao Qing Long Tang combined with Bu Zhong Yi Qi Tang for good results.

IFurther Reading

Insights from Chen on Pulse Diagnosis (Part 1): The Essence of Pulse Types

Insights from Chen on Pulse Diagnosis (Part 2): Introductory Principles and Common Pulse Pathologies

ICopyright Statement

-

Author: Dong Xuefeng, Editor: Yuan Tao.

-

This article is excerpted from Illustrated Pulse Diagnosis, and the copyright belongs to the relevant rights holders. Sharing this article is for the purpose of dissemination and learning exchange. If there are any improper uses, please feel free to contact us.

I Submission Email: [email protected]