In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the practice of observation diagnosis (望诊, wàng zhěn) involves the purposeful observation of visible signs and excretions from the body to understand health or disease states.

Observation diagnosis is a profound field of study that requires multidisciplinary knowledge. The application of Chinese physiognomy (相学, xiàng xué) to TCM observation diagnosis enhances its effectiveness. Clinically, many diseases can sometimes be intuitively recognized at a glance, encapsulated in the phrase “to know by observation is called spirit (神, shén).” The observation of spirit, color, and form holds significant importance in TCM diagnostics. Historical texts such as the “Huangdi Neijing (内经)” and “Shanghan Lun (伤寒论)” document relevant information about observation diagnosis. In 1875, Wang Hong (汪宏) compiled the “Wangzhen Zunjing (望诊遵经),” which systematically summarized historical literature on observation diagnosis, marking the beginning of its standardization. This work elaborates on the fundamental principles and guidelines of observation diagnosis, including the timing, mental state, and the relationships between various body parts and the five organs, as well as the connections to seasonal changes, geographical directions, temperament, age, and lifestyle. It analyzes and compares the shape, color, and sweat, blood, urine, and stool characteristics from various body parts to discern the nature of diseases, including their internal and external manifestations, deficiency and excess, cold and heat, and yin and yang, while predicting their prognosis. The “Wangzhen Zunjing” is well-founded, rich in content, and combines the experiences of predecessors with personal clinical insights. Today, there are numerous academically valuable texts on observation diagnosis. Over the years, I have also focused on learning and exploring observation diagnosis, and I now present the following summarized content: Overall Observation Diagnosis Overall observation diagnosis involves understanding disease conditions through the observation of changes in the spirit, color, form, and state of the entire body. Although tongue diagnosis and facial color diagnosis pertain to the head and face, they accurately reflect internal organ changes. This article will briefly introduce the unique traditional TCM diagnostic methods of observing spirit, facial color, and tongue diagnosis.

1Observation of Spirit (望神, wàng shén)

Observation of spirit is one of the main components of observation diagnosis. Spirit refers to the overall vitality of life activities, and a normal person possesses both form and spirit. It is expressed through the gaze, facial expressions, body movements, speech, and responsiveness. The concept of spirit can be understood in both broad and narrow senses: in a broad sense, spirit refers to the external manifestation of life activities; in a narrow sense, it refers to mental activities. Observation of spirit should encompass both aspects.Spirit is a function based on essence and qi (气, qì), and it is the external manifestation of the five organs. By observing spirit, one can understand the vitality of the five organs and the severity and prognosis of the disease. Key observations should focus on the patient’s mental state, consciousness, facial expressions, body movements, and responsiveness, particularly the changes in the gaze. The content of spirit observation includes gaining spirit, losing spirit, and false spirit, as well as insufficient spirit and abnormal mental states.1Gaining Spirit (得神, dé shén)

Gaining spirit, also known as having spirit, is a manifestation of abundant essence and qi, indicating that although the patient is ill, the righteous qi remains intact, suggesting a mild condition and a good prognosis. Signs of gaining spirit include: clear consciousness, coherent speech, a rosy and moist complexion, natural and rich expressions; bright eyes with inner vitality; quick responses, agile movements, and a relaxed posture; steady breathing and well-toned muscles.

2Losing Spirit (失神, shī shén)

Losing spirit, also known as having no spirit, is a manifestation of depleted essence and qi, indicating a severe condition with a poor prognosis. Signs of losing spirit include: lethargy, unclear speech, or confusion, wandering aimlessly, or collapsing with closed eyes and open mouth; a dull complexion, apathetic or stiff expressions; dull eyes with a vacant gaze; slow responses, impaired movements, and forced postures; weak or labored breathing; and significant muscle wasting.

3False Spirit (假神, jiǎ shén)

False spirit refers to a temporary improvement in the spirit of critically ill patients, which is a sign of impending danger rather than a good omen. Signs of false spirit include: a long-term ill patient who has lost spirit suddenly appearing more spirited, with bright eyes and excessive chatter, wanting to see loved ones; or a patient whose voice suddenly becomes loud after being weak and intermittent; or a patient whose complexion suddenly changes from dull to flushed; or a patient who suddenly develops an appetite after having none. The distinction between false spirit and genuine improvement lies in the suddenness of false spirit, which does not correspond to the overall condition of the disease and is merely temporary and localized. The appearance of false spirit is due to extreme depletion of essence and qi, where yin cannot contain yang, leading to a temporary “improvement” that exposes the imminent danger of separation between yin and yang, likened by ancient texts to a “flickering lamp” or “reflected light.”

4Insufficient Spirit (神气不足, shén qì bù zú)

Insufficient spirit is a mild form of losing spirit, differing only in degree. It lies between having spirit and lacking spirit, commonly seen in patients with deficiency syndromes. Clinical manifestations of insufficient spirit include: lack of energy, forgetfulness, drowsiness, low voice, reluctance to speak, lethargy, and sluggish movements. This is often associated with deficiency of both heart and spleen, or insufficient kidney yang.

5Abnormal Mental State (神志异常, shén zhì yì cháng)

Abnormal mental states are also a manifestation of losing spirit, but they differ fundamentally from losing spirit due to depletion of essence and qi. This generally includes restlessness and conditions such as mania, delirium, and other mental disorders. These are determined by specific pathological mechanisms and disease patterns, and their manifestations do not necessarily indicate the severity of the condition. Restlessness refers to a feeling of heat and agitation in the heart, with restless hands and feet. Restlessness is a subjective symptom, while agitation is an objective symptom, such as mania or hyperactivity, often related to excess heat in the heart. It can be seen in conditions of internal heat, phlegm-heat disturbing the heart, or yin deficiency with excess fire. Mania is characterized by wild behavior, shouting, and destructive actions, often due to liver qi stagnation transforming into fire, or phlegm-heat disturbing the spirit. Epilepsy presents as sudden loss of consciousness, drooling, and convulsions, returning to normal afterward, often due to liver wind with phlegm obstructing the clear orifices, or phlegm-heat disturbing the heart, leading to liver wind.

2Observation of Facial Color (望面色, wàng miàn sè)

Normal facial color is rosy and radiant, indicating sufficient qi and blood and robust organ function. Due to disease, a patient’s facial color may exhibit abnormal changes, referred to as “disease color (病色, bìng sè).” Disease colors are generally classified into five types: blue, red, yellow, white, and black.

1Blue Color (青色, qīng sè)

Indicates cold syndromes, pain syndromes, blood stasis syndromes, pediatric convulsions, and liver diseases. It signifies obstruction of the meridians and poor circulation of qi and blood.

2Red Color (红赤, hóng chì):

Indicates heat syndromes. It is a manifestation of blood filling the skin’s vessels. When the body is hot, blood circulation accelerates, leading to a flushed face. A fully flushed face indicates excess heat, while a pale red appearance on the cheeks in chronic illness often indicates low-grade fever or a sensation of heat, suggesting deficiency heat. In long-term patients, a complexion that alternates between pale and red indicates a critical condition of true cold and false heat.

3Yellow Color (黄色, huáng sè):

Indicates dampness syndromes and deficiency syndromes. A pale yellow complexion with no luster indicates spleen and stomach qi deficiency, leading to insufficient qi and blood. A complexion resembling orange peel and yellowing of the sclera indicates dampness. A yellow and emaciated complexion is often seen in gastric diseases with deficiency heat; a pale yellow complexion indicates gastric diseases with deficiency cold.

4White Color (白色, bái sè):

Indicates deficiency cold syndromes and blood deficiency syndromes. A white and swollen complexion indicates deficiency cold. A pale and emaciated complexion indicates blood deficiency. A sudden pale complexion, excessive sweating, and cold extremities indicate a critical condition of yang qi collapse or excessive blood loss. White spots or patches on the face are often seen in patients with intestinal parasites.

5Black Color (黑色, hēi sè):

Indicates kidney deficiency syndromes, cold syndromes, pain syndromes, blood stasis syndromes, and water retention syndromes. Cold, pain, and blood stasis syndromes lead to kidney yang deficiency, causing water retention and poor blood circulation, resulting in a black complexion. Dark circles around the eyes indicate phlegm retention.

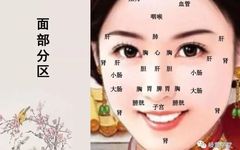

3Observation of the Head and Face (望头面部, wàng tóu miàn bù)

1Observation of the Head (望头, wàng tóu):

Observation of the head primarily involves examining the shape, dynamics, and hair quality and loss to understand brain and kidney changes and the vitality of qi and blood. (1) Observation of Head Shape: In children, an excessively large or small head accompanied by intellectual disability often indicates congenital insufficiency and kidney essence deficiency. An enlarged head may be due to hydrocephalus. In examining a child’s head, it is essential to assess the fontanelle. If the fontanelle is sunken, it indicates fluid loss and insufficient brain marrow; if it is bulging, it indicates excessive heat evil, often seen in brain diseases. If a child’s fontanelle fails to close, it is termed “open fontanelle,” indicating insufficient kidney qi and developmental issues. Whether in adults or children, an inability to control head movements indicates internal wind of the liver. (2) Observation of Hair: Normal hair is thick, black, and lustrous, indicating abundant kidney qi. Sparse or slow-growing hair indicates kidney qi deficiency. Yellow and dry hair, or hair loss in chronic illness, often indicates insufficient essence and blood. Sudden patchy hair loss is due to blood deficiency and wind. Hair loss in adolescents often results from kidney deficiency or blood heat. Premature graying in youth, accompanied by forgetfulness and weakness in the lower back and knees, indicates kidney deficiency; if there are no other symptoms, it is not pathological. In children, hair that is knotted like a tuft is often seen in malnutrition. 2Observation of the Face (望面部, wàng miàn bù):

The observation of facial color has been discussed previously. Here, we focus on changes in facial shape. Facial swelling is often seen in edema. Swelling of one or both sides of the jaw, gradually enlarging and painful to touch, often accompanies throat pain or hearing loss, indicating warm toxin, as seen in mumps. Facial asymmetry, where the mouth or eyes are crooked, often indicates a stroke. A frightened expression is commonly seen in children with convulsions or rabies, while a grimace is seen in tetanus patients.

3Observation of the Five Organs (望五官, wàng wǔ guān)

Observation of the five organs involves examining the eyes, nose, ears, lips, mouth, gums, and throat. Observing abnormalities in these organs can provide insights into internal organ diseases.

1. Observation of the Eyes (望目, wàng mù):

(1) Eye Spirit: The presence or absence of spirit in the eyes is a key focus of spirit observation. Clear vision, inner vitality, and abundant spirit indicate the eyes have spirit; if the whites of the eyes are cloudy, the pupils are dull, and the eyes lack vitality, they are considered to lack spirit.

(2) Eye Color: If the eyes are red, it indicates heart fire; if the whites are red, it indicates lung fire; if the whites show red vessels, it indicates excess fire due to yin deficiency; if the eyelids are red, swollen, and ulcerated, it indicates phlegm fire; if the entire eye is red and swollen with tears in the wind, it indicates liver wind-heat. If the eyes are pale, it indicates blood deficiency. Yellowing of the whites indicates jaundice. Dark circles around the eyes indicate kidney deficiency and water retention.

(3) Eye Shape: Slight swelling of the eyes, resembling a “sleeping worm,” indicates the onset of edema; in the elderly, facial swelling often indicates kidney qi deficiency. Sunken eye sockets indicate depletion of yin fluids or extreme depletion of essence and qi. Bulging eyes indicate lung distension; protruding eyes indicate goiter.

(4) Eye State: If the eyes are fixed and cannot move, it is termed “fixed gaze,” often seen in convulsions, seizures, or severe conditions of spirit collapse. Crossed eyes indicate internal wind of the liver. Drooping eyelids, termed “eyelid failure,” may be congenital or acquired due to qi deficiency or post-traumatic qi and blood imbalance. Uneven eyelid drooping may indicate post-traumatic qi and blood imbalance. Dilated pupils often indicate extreme depletion of kidney essence, a sign of imminent danger.

2. Observation of the Nose (望鼻, wàng bí):

The observation of the nose primarily involves examining its color, shape, and secretions.

(1) Nose Color: A bright and moist nose indicates intact stomach qi or recovery of stomach qi after illness. A red nose tip indicates lung heat; a white nose indicates qi deficiency and blood deficiency; a yellow nose indicates internal damp-heat; a blue nose often indicates abdominal pain; a slightly black nose indicates internal water retention.

The nose tip may be dry, indicating spleen and stomach deficiency, where stomach qi cannot nourish the nose. Dry nostrils indicate internal heat due to yin deficiency or dryness invading the lungs; if the nose is dry and bleeds, it often indicates excessive yang.

(2) Nose Shape: A red nose tip or nose with papules often indicates rosacea, caused by stomach fire affecting the lungs and blood stasis in the lung vessels. If there are growths inside the nostrils that block airflow, it is termed “nasal polyps,” often due to wind-heat stagnation in the lung meridian. Frequent flaring of the nostrils with rapid breathing indicates “nasal flaring.” If this occurs in chronic illness, it indicates critical lung and kidney qi deficiency; in acute illness, it often indicates lung heat.

(3) Nasal Secretions: Clear nasal discharge indicates external wind-cold; turbid nasal discharge indicates external wind-heat; foul-smelling turbid discharge indicates nasal phlegm, often due to external wind-heat or heat accumulation in the gallbladder.

3. Observation of the Ears (望耳, wàng ěr):

Observation of the ears should focus on their color, shape, and internal conditions.

(1) Ear Color: Normal ear color is slightly yellow and rosy. A predominantly white ear color often indicates cold syndromes; a blue-black ear color often indicates pain syndromes; a dry, black ear indicates extreme kidney essence deficiency; a cool ear root often indicates a precursor to numbness. Ear color should ideally be rosy; yellow, white, blue, or black colors indicate pathological conditions.

(2) Ear Shape: Normal ears are thick and moist, indicating sufficient kidney qi. If the ear is thick, it indicates excess; if thin, it indicates deficiency. Enlarged ears indicate excess evil; thin ears indicate deficiency of righteous qi. Thin and red or black ears indicate kidney essence deficiency. Dry, black ears are often seen in lower body deficiency syndromes. Wrinkled ears are often seen in chronic blood stasis. Atrophied ears indicate critical kidney qi depletion.

(3) Internal Ear Changes: Pus in the ear indicates ear infection, often due to long-standing liver and gallbladder damp-heat. Growths resembling sheep’s teats in the ear, or those resembling jujube pits, are termed “ear polyps” or “ear protrusions,” which are painful to touch, often due to liver fire or kidney fire, or heat accumulation in the stomach.

4. Observation of the Lips and Mouth (望口与唇, wàng kǒu yǔ chún):

(1) Observation of the Lips: The clinical significance of lip color diagnosis is similar to that of facial color, but due to the thin and transparent mucosa of the lips, their color is often more pronounced than that of the face. Normal lips are red and moist. Deep red lips indicate excess or heat; pale red lips often indicate deficiency or cold; dry, cracked, and deep red lips indicate extreme heat damaging fluids; tender red lips indicate excess fire due to yin deficiency; pale lips often indicate deficiency of both qi and blood; bluish-purple lips often indicate deficiency of yang qi and stagnation of blood. Dry, cracked lips indicate damage to fluids, leading to loss of moisture. Ulcerated lips often result from heat accumulation in the spleen and stomach.

(2) Observation of the Mouth: The shape of the mouth should also be noted: a closed mouth indicates difficulty in opening; if the mouth is closed and silent, accompanied by limb convulsions, it often indicates convulsions or seizures; if accompanied by hemiplegia, it indicates a severe stroke. A tightly closed mouth indicates a condition often seen in children with umbilical wind or adults with tetanus. A crooked mouth indicates a stroke.

5. Observation of the Teeth and Gums (望齿与龈, wàng chǐ yǔ yín):

(1) Observation of the Teeth: Teeth that lack luster indicate uninjured fluids. Dry teeth indicate damage to stomach fluids; teeth that are dry as stone indicate extreme heat in the stomach and intestines, leading to severe fluid loss; dry teeth resembling dried bones indicate depletion of kidney essence, unable to nourish the teeth; loose and sparse teeth with exposed roots often indicate kidney deficiency or excess fire. Grinding teeth during sleep often indicates internal wind of the liver. Teeth that are worn down during sleep often indicate stomach heat or parasitic accumulation.

(2) Observation of the Gums: Healthy gums are red and moist. Pale gums indicate blood deficiency; swollen or bleeding gums often indicate stomach fire. Slightly red, swollen, and painless gums, or bleeding between the teeth, often indicate kidney yin deficiency with excess fire; pale, non-swollen gums with bleeding between the teeth indicate spleen deficiency unable to control blood. Ulcerated gums with foul-smelling blood indicate dental disease.

6. Observation of the Throat (望咽喉, wàng yān hóu):

Throat disorders present various symptoms; here, we will only introduce the generally observable content. If the throat is red, swollen, and painful, it often indicates accumulation of heat in the lungs and stomach; if red and ulcerated with yellow-white necrotic spots, it indicates deep heat toxin; if it is bright red and tender with mild swelling, it indicates excess fire due to yin deficiency.

If the sides of the throat are red and swollen, resembling papillae, it is termed “papillary throat,” indicating excess heat in the lungs and stomach, with external wind evil accumulating. If there is a gray-white membrane in the throat that cannot be wiped away, and wiping causes bleeding, it indicates diphtheria, which is infectious and is also known as “epidemic throat.”

4Observation of the Limbs (望四肢, wàng sì zhī)Primarily involves examining the shape and color changes of the hands, feet, palms, wrists, fingers, and toes. This section will focus on hand diagnosis methods:

Examine the color of the palms. For healthy individuals of the yellow race, the primary color of the palms should be a subtle red-yellow. The following are abnormal signs: blue color indicates blood stasis diseases; red palms often indicate heat syndromes; deep red color in the thenar and hypothenar indicates hypertension or liver cirrhosis; if the redness intensifies in a short period, it is often a warning sign of cerebral hemorrhage; white color often indicates qi and blood deficiency; red and white spots covering the entire palm indicate digestive dysfunction or endocrine disorders; black or brown spots may indicate malignant diseases.

Examine the length of the fingers. The thumb should reach halfway to the third segment of the index finger; if not, it indicates a tendency to develop liver fire; the index finger should reach halfway to the first segment of the middle finger; if it is short, it often indicates poor spleen and stomach function; if the middle finger is lower than the ring and index fingers, it indicates a tendency to heart disease; if it is too long, it is often associated with lower back pain; if the ring finger is shorter than the index finger, it may indicate poor heart and brain function; the little finger should reach the horizontal line of the second segment of the ring finger; if not, it indicates poor reproductive function; if the starting position of the little finger is lower but the total length is standard, it is still considered normal.

Examine the shape and color of the nails. Blue nails indicate poor heart function, hypoxia, or blood stasis; overly red nails indicate heat syndromes; yellow nails often suggest digestive system diseases; white nails often indicate malnutrition; if the nail surface has white spots, it may indicate intestinal parasitic diseases; black nails indicate severe heart blood stasis; if a longitudinal black line appears on the nail surface of the thumb, it often indicates elevated blood lipids, a precursor to arteriosclerosis.

5Observation of Children’s Fingerprints (望小儿指纹, wàng xiǎo ér zhǐ wén)

Fingerprints are the vascular patterns visible on the front edge of the index fingers of children. The method of observing changes in children’s fingerprints to diagnose diseases is called “fingerprint diagnosis (指纹诊法, zhǐ wén zhěn fǎ),” applicable only to children under three years old. Fingerprints are a branch of the hand taiyin lung meridian, thus similar in significance to pulse diagnosis.

Fingerprints are divided into three sections: “wind (风, fēng),” “qi (气, qì),” and “life (命, mìng).” The first section near the palm of the index finger is the “wind section,” the second section is the “qi section,” and the third section is the “life section.”

(1) Method of Observing Fingerprints

Hold the child in a well-lit area, using the left hand’s index and thumb to grasp the tip of the child’s index finger. With the right thumb, gently push from the life section towards the qi and wind sections several times, applying appropriate pressure to make the fingerprints more visible for observation.

(2) Clinical Significance of Fingerprints

Normal fingerprints are light red with a hint of purple, often not prominent, and mostly appear as slanted, single branches of moderate thickness.

1. Changes in Fingerprint Position – Assessing Severity: The position of the fingerprint indicates the depth of the evil qi and the severity of the disease. If the fingerprint appears near the wind section, it indicates superficial evil and a mild condition; if it extends from the wind section to the qi section, it indicates deeper evil and a more severe condition; if it reaches from the qi section to the life section, it indicates deep-seated disease; if the fingerprint extends through all three sections to the nail tip, it is termed “penetrating the sections and reaching the nail,” indicating critical illness.

2. Changes in Fingerprint Color – Differentiating Cold and Heat: Changes in fingerprint color include red, purple, blue, black, and white. Bright red often indicates external wind-cold; purple-red often indicates heat syndromes; blue often indicates wind or pain syndromes; blue-purple or purple-black indicates blood stasis; pale white often indicates spleen deficiency.

3. Changes in Fingerprint Shape – Differentiating Surface and Interior, Deficiency and Excess: Changes in fingerprint shape include depth, fineness, and thickness. If the fingerprint is prominent and floating, it indicates a surface condition; if it is deep and hidden, it indicates an internal condition. Fine and light fingerprints often indicate deficiency syndromes; thick and dark fingerprints often indicate excess syndromes.

In summary, the key points of observing children’s fingerprints are: differentiating surface and interior, identifying cold and heat, determining deficiency and excess, assessing severity, and observing the shape and color of the fingerprints carefully. The hand is a microcosm of the human body, and through hand diagnosis, abnormalities can often be detected. In fact, we can also achieve health and assist in treatment through localized interventions (such as acupuncture, massage, etc.). One of the easiest methods is “clapping hands.” The key is to relax the joints of the shoulders, elbows, wrists, and fingers, using one hand (left or right) to clap the palm and back of the other hand for 5-10 minutes daily to strengthen the body.

6Observation of the Tongue (望舌, wàng shé)

Observation of the tongue, also known as tongue diagnosis, is a unique diagnostic method that assesses changes in the tongue’s quality and state, including its shape, color, moisture, and dryness, to gauge disease conditions. Tongue diagnosis primarily involves observing the tongue’s appearance, but it also includes tongue sensation (taste) and palpation. Tongue observation is one of the diagnostic methods in TCM. The tongue’s appearance consists of the tongue body and the tongue coating. Tongue observation is one of the five organ examinations. However, its content is very rich and has developed into a specialized field of tongue diagnosis, thus warranting a separate section for elaboration.

(1) Relationship Between the Tongue and Internal Organs

The relationship between the tongue and internal organs is primarily realized through the pathways of the meridians. According to the “Huangdi Neijing,” the heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and bladder, as well as the three burners and stomach, are directly connected to the tongue through the meridians. Although the lungs, small intestine, large intestine, and gallbladder do not have direct connections to the tongue, the hand and foot taiyin correspond, as do the hand and foot yangming, and the hand and foot shaoyang, allowing the qi of the lung, small intestine, gallbladder, and large intestine to indirectly connect to the tongue. Therefore, the tongue is not only the external manifestation of the heart but also reflects the conditions of the five internal organs. Physiologically, the essence and qi of the internal organs can reach the tongue through the meridians, nourishing the tongue and maintaining its normal function. Pathologically, changes in the internal organs must also affect the essence and qi, reflecting on the tongue. From the perspective of biological holism, any local area resembles a microcosm of the whole, and the tongue is no exception. Thus, ancient texts state that the tongue corresponds to specific internal organ locations. The basic principle is: the upper part corresponds to the upper organs, the middle part corresponds to the right organs, and the lower part corresponds to the lower organs. The specific classification methods are as follows: 1. By organ affiliation: the heart and lungs are located at the top, thus the tip of the tongue corresponds to the heart and lungs; the spleen and stomach are in the middle, thus the middle part of the tongue corresponds to the spleen and stomach; the kidneys are at the bottom, thus the root of the tongue corresponds to the kidneys; the liver and gallbladder are located on the sides of the body, thus the sides of the tongue correspond to the liver and gallbladder, with the left side corresponding to the liver and the right side corresponding to the gallbladder. This classification is generally used for internal injuries and miscellaneous diseases. 2. By the three burners: the tongue is classified according to the positions of the three burners, with the tip corresponding to the upper burner, the middle part corresponding to the middle burner, and the root corresponding to the lower burner. This classification is often used for external pathogenic changes. 3. By the stomach: the tip of the tongue corresponds to the upper stomach, the middle part corresponds to the middle stomach, and the root corresponds to the lower stomach. This classification is commonly used for gastrointestinal diseases. The relationship between the tongue and internal organs is one of the current research topics in biological holism. Although there are various interpretations, they all hold reference value. In clinical diagnosis, it is essential to combine tongue quality and tongue coating observations for verification, but all four diagnostic methods should be considered together for comprehensive judgment, avoiding overly mechanical adherence to any one method.

(2) Content of Tongue Observation

The content of tongue observation can be divided into two parts: tongue quality and tongue coating. Tongue quality, also known as the tongue body, refers to the muscle and vascular tissues of the tongue. Tongue quality observation is further divided into four aspects: spirit, color, shape, and state. Tongue coating is a layer of material attached to the tongue body, and tongue coating observation can be divided into two aspects: coating color and coating quality. A normal tongue appearance is referred to as “light red tongue with thin white coating.” Specifically, the tongue body should be soft, flexible, and of moderate size, with a light red color that is bright and vivid; it should be of normal thickness, without abnormal shapes; the tongue coating should be thin, white, and moist, evenly distributed over the tongue surface, easily removable, and should not be sticky or greasy. In summary, the combined normal appearance of the tongue body and coating represents a normal tongue appearance. 1. Observation of Tongue Quality (1) Tongue Spirit: Tongue spirit is primarily reflected in the luster and vitality of the tongue. The key to assessing tongue spirit is to distinguish between vitality and dullness. Vitality is characterized by a moist and radiant appearance, indicating flexible movement, a rosy color, and abundant vitality, which is considered auspicious, even in illness. Dullness is characterized by a dry and lifeless appearance, indicating poor movement and a lack of vitality, which is considered ominous. The presence or absence of tongue spirit reflects the vitality of the internal organs, qi, blood, and fluids, which is related to the prognosis of the disease. (2) Tongue Color: Tongue color can generally be classified into light white, light red, red, dark red, purple, and blue. Except for light red, which is considered normal, the other colors indicate pathological conditions. ① Light Red Tongue: A tongue color that is pale red, neither too deep nor too shallow, indicates sufficient qi and blood, reflecting the heart’s vitality and yang qi’s distribution, thus considered a normal tongue color. ② Light White Tongue: A tongue color that is lighter than light red, even lacking blood color, is termed light white tongue. This indicates a deficiency of yang qi, leading to reduced blood circulation, resulting in a pale tongue. Therefore, this tongue indicates deficiency cold or dual deficiency of qi and blood. ③ Red Tongue: A tongue that is bright red, deeper than light red, is termed red tongue. This indicates excess heat, resulting in abundant qi and blood filling the tongue, thus appearing bright red, indicating heat syndromes. This can be seen in excess syndromes or deficiency heat syndromes. ④ Dark Red Tongue: A dark red tongue is deeper than a red tongue. This indicates different diseases based on external and internal injuries. In external diseases, it indicates heat entering the nutrient and blood levels; in internal diseases, it indicates excess fire due to yin deficiency. ⑤ Purple Tongue: A purple tongue is primarily caused by poor blood circulation and stasis. Therefore, purple tongues indicate diseases, primarily differentiating between cold and heat. Excess heat damages fluids, leading to a dry and purple tongue; cold congealing blood stasis or yang deficiency leading to a pale purple or blue-purple moist tongue. ⑥ Blue Tongue: A tongue that appears blue, resembling exposed “blue veins,” indicates a lack of red color, often due to excess cold and yin, leading to stagnation of blood. (3) Tongue Shape: This refers to the shape of the tongue body, including age, thickness, swelling, cracks, prickles, and teeth marks. ① Old Tongue: A tongue with rough texture and a firm appearance is termed old tongue. Regardless of tongue color or coating, an old tongue indicates an excess condition. ② Tender Tongue: A tongue with a delicate texture, tender color, and often swollen appearance is termed tender tongue, often indicating deficiency syndromes. ③ Swollen Tongue: This can be classified into fat and swollen. A tongue that is larger than normal, even filling the mouth, or has teeth marks, is termed fat tongue. A swollen tongue that cannot retract or close is termed swollen tongue, often due to phlegm-damp obstruction. A swollen tongue is often due to heat toxin or alcohol toxicity causing qi and blood stagnation, indicating heat syndromes or toxic diseases. ④ Thin Tongue: A tongue that is thin and small is termed thin tongue, often due to deficiency of qi, blood, and fluids, leading to an inability to nourish the tongue. This indicates dual deficiency of qi and blood or excess fire due to yin deficiency. ⑤ Prickly Tongue: A tongue with enlarged soft papillae (normal state) is termed prickly tongue. If the papillae are enlarged and raised, causing discomfort, it indicates excess heat. The more prickles present, the more severe the heat. The location of prickles can help differentiate heat in the internal organs, such as prickles on the tongue tip indicating excess heart fire; prickles on the sides indicating excess liver and gallbladder fire; prickles in the middle indicating excess stomach and intestinal heat. ⑥ Cracked Tongue: A tongue with cracks that are not covered by coating is termed cracked tongue, often due to depletion of essence and blood, leading to loss of nourishment. Therefore, it often indicates deficiency of essence and blood. Additionally, about 0.5% of healthy individuals may have deep grooves on the tongue, termed congenital tongue fissures, which are covered by coating and do not indicate discomfort, differing from cracked tongues. ⑦ Teeth Marks: A tongue with indentations along the edges from teeth is termed teeth-marked tongue. This is often due to spleen deficiency, leading to water retention, causing the tongue to swell and become pressed by the teeth, resulting in teeth marks. Therefore, teeth marks are often seen with a fat tongue, indicating spleen deficiency or excess dampness. (4) Tongue State: This refers to the state of the tongue during movement. A normal tongue state is characterized by flexible movement; pathological states include rigidity, weakness, elongation, shortening, numbness, trembling, tilting, and protruding. ① Rigidity: A tongue that is stiff and rigid, with poor movement, leading to unclear speech, is termed rigid tongue. This often results from heat disturbing the heart spirit, leading to loss of control, or high fever damaging yin, causing muscle and meridian malnourishment, or phlegm obstructing the tongue. This is often seen in conditions of heat entering the pericardium, high fever damaging fluids, phlegm obstructing, or as a precursor to stroke. ② Weakness: A tongue that is weak and lacks strength to extend or retract is termed weak tongue. This often results from extreme deficiency of qi and blood, leading to loss of nourishment. This can be seen in conditions of dual deficiency of qi and blood, extreme heat damaging fluids, or severe yin deficiency. ③ Elongation: A tongue that extends beyond the mouth and is difficult to retract is termed elongated tongue. This is often due to relaxation of the tongue muscles, seen in conditions of internal excess heat, phlegm disturbing the heart, or qi deficiency. ④ Shortening: A tongue that is contracted and cannot extend is termed shortened tongue. This can be due to cold congealing the muscles, phlegm obstructing, or heat damaging fluids, leading to contraction; or due to qi and blood deficiency, leading to loss of nourishment. Regardless of whether it is due to deficiency or excess, it indicates a critical condition. ⑤ Numbness: A tongue that feels numb and cannot move is termed numb tongue. This often results from the inability of nutrients to reach the tongue. If the numbness occurs without reason and is intermittent, it indicates heart blood deficiency; if the tongue is numb and trembles, or shows symptoms of stroke, it indicates internal wind of the liver. ⑥ Trembling: A tongue that trembles uncontrollably is termed trembling tongue. This often results from dual deficiency of qi and blood, leading to loss of nourishment, or extreme heat damaging fluids, leading to wind. This can be seen in conditions of blood deficiency leading to wind or extreme heat leading to wind. ⑦ Tilting: A tongue that tilts to one side is termed tilted tongue. This often results from wind evil obstructing the meridians or phlegm obstructing the meridians, but it can also indicate wind affecting the internal organs, leading to one side of the tongue muscles relaxing, causing it to tilt towards the healthy side. This is often seen in stroke conditions or as a precursor to stroke. ⑧ Protruding: A tongue that frequently extends outside the mouth is termed “protruding tongue”; if the tongue licks the lips or moves around the mouth, it is termed “playing with the tongue.” Both are referred to as protruding tongue, often due to heat in the heart and spleen damaging fluids, leading to frequent movement. This is often seen in children with developmental delays. 2. Observation of Tongue Coating: The normal tongue coating is produced by the upward steaming of stomach qi, thus the changes in stomach qi can be reflected in the tongue coating. Pathological tongue coating forms due to the upward movement of turbid qi from food stagnation or due to the rise of pathogenic qi. When observing tongue coating, attention should be paid to both coating quality and coating color. (1) Coating Quality: Coating quality refers to the texture of the tongue coating, including thickness, moisture, dryness, roughness, stickiness, peeling, and whether it has roots. ① Thickness: Thickness is assessed by whether the tongue body is visible or not. If the tongue body is faintly visible through the coating, it is termed thin coating. This is produced by stomach qi and is considered normal; if seen in disease, it often indicates the early stage of illness or superficial pathogenic qi, indicating a milder condition. If the tongue body cannot be seen through the coating, it is termed thick coating. This often indicates deep-seated pathogenic qi or food stagnation, indicating a more severe condition. If the coating changes from thin to thick, it indicates that the righteous qi is unable to overcome the pathogenic qi, and the condition is worsening; if the coating changes from thick to thin, it indicates that the righteous qi is recovering, and the internal pathogenic qi is dissipating, indicating improvement. ② Moisture and Dryness: A moist tongue surface indicates adequate moisture, while a dry tongue indicates a lack of fluids. If the coating is excessively moist, it feels slippery and may even drip with saliva, indicating dampness and cold, often seen in yang deficiency with phlegm and water retention. If the coating appears dry and rough, it indicates dryness due to insufficient fluids, often seen in conditions of excess heat damaging fluids, or severe yin deficiency. Changes from moist to dry indicate worsening conditions; changes from dry to moist indicate improvement. ③ Roughness: A thick coating with coarse, loose particles resembling tofu curds on the tongue surface is termed rough coating. This is due to excess heat in the body, leading to the upward movement of turbid qi from the stomach. It is often seen in phlegm and food stagnation, with signs of gastrointestinal heat. A coating that is fine and dense, which cannot be removed, is termed sticky coating, often indicating spleen deficiency with internal dampness, leading to stagnation of yang qi. ④ Peeling: If the tongue initially has coating that suddenly peels off entirely or partially, revealing the tongue body, it is termed peeling coating. If the entire coating peels off without regrowth, leaving a smooth surface, it is termed mirror tongue or smooth tongue, indicating severe depletion of stomach yin and qi. Regardless of color, this indicates a critical condition of stomach qi. If the coating partially peels off, leaving a smooth area while the rest remains, it is termed mottled peeling coating, indicating dual injury to stomach qi and yin. Changes from having coating to none indicate insufficient stomach qi and yin, with declining righteous qi; however, if a thin white coating regrows after peeling, it indicates that the pathogenic qi has been expelled and the stomach qi is recovering, which is a good sign. It is important to note that whether the coating increases or decreases, it should change gradually; sudden changes in coating thickness often indicate a rapid change in the condition. ⑤ Coating with Roots vs. Without Roots: Regardless of thickness, if the coating adheres closely to the tongue surface, appearing to grow from within, it is termed rooted coating, also known as true coating; if the coating is not firmly attached and can be easily scraped off, it is termed unrooted coating, also known as false coating. Rooted coating indicates that while the pathogenic qi is strong, the stomach qi is still intact; unrooted coating indicates that the stomach qi has weakened. In summary, observing the thickness of the tongue coating can indicate the depth of the disease; observing moisture and dryness can indicate the balance of fluids; observing roughness can indicate dampness; observing peeling and rooted vs. unrooted can indicate the state of qi and yin and the trend of the disease. (2) Coating Color: Coating color refers to the color of the tongue coating, generally classified into white, yellow, gray, and black, along with variations. Since coating color is related to the nature of the pathogenic qi, observing coating color can help understand the nature of the disease. 1) White Coating: Commonly seen in exterior syndromes and cold syndromes. When external pathogenic qi has not yet penetrated, the tongue coating often remains normal and thin. If the tongue is pale with a moist white coating, it often indicates internal cold or damp-cold syndromes. However, in special cases, white coating can also indicate heat syndromes. For example, if the tongue is covered with thick white coating resembling a powdery substance, it is termed “powdery coating,” indicating the presence of external pathogenic qi or internal heat. This is often seen in warm epidemics or internal abscesses. If the coating is white, dry, and cracked like sand, it indicates rapid transformation of dampness into heat, with internal heat rising quickly, often seen in warm diseases or improper use of warming herbs. 2) Yellow Coating: Generally indicates internal syndromes and heat syndromes. Due to heat evil scorching, the coating appears yellow. Light yellow indicates mild heat, deep yellow indicates severe heat, and scorched yellow indicates heat accumulation. In external diseases, a change from white to yellow indicates that the exterior evil has penetrated and transformed into heat. If the coating is thin and light yellow, it indicates external wind-heat or wind-cold transforming into heat. If the tongue is pale and plump with a yellow, slippery coating, it often indicates yang deficiency with water retention. 3) Gray Coating: Gray coating is a light black color, often resulting from a transformation of white coating or appearing alongside yellow coating. It generally indicates internal syndromes, often seen in heat syndromes, but can also be seen in cold-warm syndromes. Dry gray coating often indicates severe heat damaging fluids, seen in external heat diseases or internal heat due to yin deficiency. Moist gray coating can indicate phlegm and water retention or internal dampness. 4) Black Coating: Black coating often develops from scorched yellow or gray coating. Generally, regardless of cold or heat, it indicates a critical condition. The darker the coating, the more severe the condition. If the coating is black and dry, it may indicate extreme heat and fluid depletion; if it is black and dry, it may indicate intestinal dryness and constipation, or impending stomach failure; if it appears at the root of the tongue, it indicates severe heat in the lower burner; if it appears at the tip, it indicates heart fire; if it is black and slippery, with a pale tongue, it indicates internal cold and water retention; if it is black and sticky, it indicates phlegm and water retention. 3. Comprehensive Diagnosis of Tongue Quality and Coating: The development of disease is a complex and holistic process, thus when analyzing the basic changes in tongue quality and coating, it is essential to also consider their interrelationship. Generally, observing tongue quality focuses on distinguishing the deficiency and excess of righteous qi, which also includes the nature of pathogenic qi; observing tongue coating focuses on distinguishing the depth and nature of pathogenic qi, which also includes the survival of stomach qi. In terms of their relationship, both must be considered together for a comprehensive understanding. In general, changes in tongue quality and coating are consistent, and their primary diseases often reflect a combination of their respective primary diseases. For example, in internal excess heat syndromes, the tongue is often red with yellow and dry coating; in internal deficiency cold syndromes, the tongue is often pale with white and moist coating. This is a key point in learning tongue diagnosis, but there are also instances where their changes are inconsistent, thus requiring comprehensive assessment. For example, a white tongue may indicate cold or dampness, but if accompanied by a red tongue with dry white coating, it indicates dryness and heat damaging fluids, suggesting rapid transformation of dampness into heat. Similarly, gray-black coating can indicate heat or cold, requiring consideration of the moisture and dryness of the tongue to differentiate. Sometimes, the primary diseases of the two may contradict each other, but they must still be assessed together. For example, a red tongue with white slippery coating may indicate heat in the nutrient level and dampness in the qi level in external diseases; in internal injuries, it may indicate excess fire due to yin deficiency, along with phlegm and food stagnation. Thus, while learning, one can distinguish between them, but in practice, comprehensive assessment is essential.

(3) Methods and Considerations for Tongue Observation

To obtain accurate results in tongue observation, it is essential to follow specific methods and pay attention to certain issues, which are outlined as follows:

1. Tongue Extension Position: During tongue observation, the patient should extend their tongue outward, fully exposing the tongue body. The mouth should be opened as much as possible, and the tongue should be relaxed without force, with the tongue surface flat and the tip naturally hanging towards the lower lip.

2. Sequence: Tongue observation should follow a specific sequence, generally starting with the tongue coating, followed by the tongue body, in the order of the tip, sides, middle, and root of the tongue.

3. Lighting: Tongue observation should be conducted in sufficient and soft natural light, facing a bright area to allow light to shine directly into the mouth, avoiding colored doors and windows or strong reflections from colored objects, which may distort the appearance of the tongue coating.

4. Diet: Diet significantly affects the appearance of the tongue; it can cause changes in the shape and color of the tongue coating. Chewing food can cause thick coating to become thin; drinking water can moisten the tongue; excessively cold or hot foods, as well as spicy or irritating foods, can alter tongue color. Additionally, certain foods or medications can stain the tongue coating, creating false appearances, termed “dyed coating.” These are temporary and do not reflect the essence of the patient’s condition. Therefore, when clinical observations of the tongue coating do not match the disease condition, or if there are sudden changes in the tongue coating, it is essential to inquire about the patient’s recent diet and medication, especially in the period leading up to the consultation.

Guilin Ancient Texts on the Secret Techniques of Observation Diagnosis from “Shanghan Lun”

Traditional Chinese Medicine Diagnostic Techniques: The Connection Between Facial Diagnosis and Disease

— THE END —

▶ Copyright Statement:

This platform aims to disseminate traditional Chinese medicine culture. Unless otherwise specified, all images and texts are sourced from the internet, and copyright belongs to the respective rights holders. If there is any improper use, please contact us for removal. Respect knowledge and labor; please retain copyright information when reprinting.Contact (Email): [email protected]