Click the above“blue text” to follow us!

Click the above“blue text” to follow us!

Through wènzhěn (consultation)

we can systematically collect patient history data

which is the primary means of gathering medical history

and a fundamental skill that clinical practitioners must master.

Consultation

is also an important opportunity for doctor-patient communication and establishing a good doctor-patient relationship.

Next,

let’s take a closer look at wènzhěn (consultation).

Consultation is a diagnostic method where the physician systematically inquires about the patient’s or related individuals’ medical history to make clinical judgments through comprehensive analysis. It is the primary means of collecting medical history and a fundamental skill that clinical practitioners must master. Most clues and evidence for diagnosing diseases come from the collection of medical history.

General Items

Include name, gender, age, place of origin, birthplace, ethnicity, marital status, contact address, phone number, workplace, occupation, admission date, record date, person providing the medical history and their reliability, etc. If the person providing the medical history is not the patient, their relationship to the patient should be noted. The recorded age should be the specific age, not replaced by terms like “child” or “adult,” as age itself has diagnostic significance. To avoid making the initial consultation too rigid, some general items like occupation and marital history can be interspersed within personal history inquiries.

Chief Complaint

Refers to the patient’s most significant pain or the most obvious symptom or sign, which is the primary reason for this visit and its duration. A more precise chief complaint can initially reflect the severity and urgency of the condition and provide diagnostic clues for certain systemic diseases. The chief complaint should be summarized in one or two sentences, indicating the time from the onset of the complaint to the visit, such as “sore throat, high fever for 2 days,” or “chills, fever, cough for 3 days, worsening with right chest pain for 2 days,” rather than using the doctor’s diagnostic terms like “heart disease for 2 years” or “diabetes for 1 year.” However, in cases with a longer course of illness or more complex conditions, where symptoms and signs are numerous, or the patient has many complaints, it may not be easy to simply summarize the main discomfort as the chief complaint. Instead, the entire medical history should be analyzed comprehensively to summarize a chief complaint that better reflects the characteristics of the illness.

Present Illness History

Onset Situation

Includes the time of onset, the rapidity of onset, causes or triggers, all of which are related to the diagnosis of the disease. For example, cerebral embolism, angina pectoris, and acute pyelonephritis all have sudden onset, while tumors and rheumatic heart disease tend to develop more slowly. Many diseases have certain causes or triggering factors before they occur, such as excitement or fatigue can trigger angina, and unclean diet can lead to acute gastroenteritis. Some patients may also mistakenly consider a coincidental situation as a cause or trigger, which should be carefully analyzed and distinguished. If several symptoms or signs appear sequentially, they should be recorded in order, such as palpitations for 3 months, dyspnea after exertion for 2 weeks, and lower limb edema for 3 days.

Main Symptom Characteristics

The same symptom can be common to different diseases. For example, upper abdominal pain can be associated with gastric or duodenal ulcers, as well as gastritis and pancreatitis. Chronic bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, and bronchiectasis also primarily present with cough. Therefore, the characteristics of the main symptoms should be comprehensively documented, including the time of occurrence, location, nature, duration, severity, and factors that relieve or exacerbate the symptoms. For instance, in cases of diarrhea and abdominal pain, bacterial dysentery may present with left lower abdominal pain and purulent bloody stools; amoebic dysentery may present with right lower abdominal pain and jam-like stools. Similarly, in peptic ulcers, the main symptom is upper abdominal pain, which may last for several days or weeks, can occur intermittently over years, and is related to food intake, with exacerbations in late autumn and early spring. Therefore, clarifying the characteristics of the main symptoms is crucial for diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Causes and Triggers

It is essential to understand whether the disease has any obvious causes or triggers. For example, acute gastroenteritis and dysentery often have a history of unclean food intake, bronchial asthma may be related to seasonal changes and allergy history; chronic bronchitis with infection is often triggered by cold exposure, while emotional agitation or alcohol consumption may trigger angina or cerebrovascular accidents. Therefore, clarifying these factors helps in making a clear diagnosis and formulating treatment measures. However, some diseases have complex causes, and patients may not be able to provide clear causes and triggers, and may present some seemingly plausible factors that should be analyzed and distinguished.

Accompanying Symptoms

These refer to other symptoms that appear simultaneously with the main symptoms. Accompanying symptoms often serve as the basis for differential diagnosis. For example, hemoptysis can be caused by various factors, and relying solely on this symptom makes it difficult to establish a clear diagnosis. Clarifying accompanying symptoms can provide a clearer direction for diagnosis. For instance, massive hemoptysis accompanied by recurrent fever, cough, and purulent foul-smelling sputum may indicate bronchiectasis; hemoptysis accompanied by long-term low fever, night sweats, fatigue, and weight loss may suggest the possibility of pulmonary tuberculosis; hemoptysis accompanied by palpitations, dyspnea, and signs of left atrioventricular valve stenosis may indicate rheumatic heart disease. Conversely, if accompanying symptoms that should generally be present are absent, this should also be recorded in the present illness history for further observation, as such negative findings often have significant diagnostic implications. For example, a patient with acute viral hepatitis may not exhibit jaundice, and a patient with nephritis may not show edema. A good medical history should not overlook any minor accompanying symptoms outside the main symptoms, as these often provide crucial clues for a definitive diagnosis.

Progression and Evolution of the Condition

During the course of the disease, changes in the main symptoms or the appearance of new symptoms can be seen as the progression and evolution of the condition. For example, a patient with chronic glomerulonephritis may develop severe anemia, nausea, vomiting, and skin itching, which may indicate the onset of chronic renal failure (uremia stage); a patient with angina may suddenly experience persistent squeezing pain in the precordial area, suggesting the possibility of myocardial infarction; similarly, a patient with chronic bronchitis may further develop into emphysema and cor pulmonale, presenting with dyspnea, fatigue, and lower limb edema. Therefore, understanding the progression and evolution of the disease aids in diagnosis and differential diagnosis.

Diagnosis and Treatment Process

Any diagnostic examinations and their results that have been conducted prior to this visit, as well as the names, dosages, routes of administration, duration, and efficacy of medications used in treatment, should be clearly documented for reference when formulating a diagnostic and treatment plan.

General Condition During the Course of Illness

The patient’s mental state, physical condition, dietary habits, sleep, and bowel and bladder function after the illness are also very useful for evaluating the patient’s overall condition and determining what auxiliary treatments to take.

Past Medical History

Includes the patient’s past health status and any diseases previously suffered (including various infectious diseases), injuries, surgeries, vaccinations, allergies, especially those closely related to the current illness.

For example, in cases of rheumatic heart valve disease, inquire about any history of migratory joint pain or throat pain; for patients with cerebrovascular accidents, inquire about any history of hypertension.

System Review

Respiratory System

Inquire about the presence of cough and the nature of the cough, the timing and exacerbation of the cough, the severity, frequency, and its relationship with climate changes and body position. Inquire about the presence of sputum and its characteristics, color, quantity, viscosity, and odor. Inquire about hemoptysis, including the timing, quantity, color, triggers, and whether there are any symptoms like dizziness, palpitations, or shock following hemoptysis. Inquire about dyspnea, including the timing, nature, and severity of the dyspnea. Inquire about chest pain, including the location, nature, and its relationship with breathing, coughing, and body position. Inquire about any history of contact with tuberculosis patients. Inquire about smoking habits and any occupational or environmental air pollution.

Circulatory System

Inquire about palpitations, including the timing and triggers; inquire about precordial pain, including its nature, severity, duration, and any radiation of pain, as well as triggers and alleviating methods. Inquire about dyspnea, including its timing, nature, and severity, and its relationship with physical activity and body position. Inquire about cough, hemoptysis, sputum; inquire about edema, including its location and timing; inquire about urine output and any abdominal distension; inquire about sudden blackouts or fainting. Inquire about any past history of rheumatic fever, hypertension, or arteriosclerosis. For female patients, inquire about any edema or palpitations during pregnancy or childbirth.

Digestive System

Inquire about abdominal pain, including the timing, location, nature, severity, radiation, and its relationship with diet and medications; inquire about accompanying symptoms like abdominal distension, acid reflux, belching, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hematemesis, melena, fever, and jaundice of the skin and mucous membranes. Inquire about any abdominal masses, including their location and size, and whether they are painful or tender. Inquire about constipation or alternating diarrhea and constipation. Inquire about nausea and vomiting, including the timing, frequency, and its relationship with diet; inquire about hematemesis, including the quantity and color, and whether it is accompanied by food or gastric juice; inquire about diarrhea, including its frequency, stool color, and whether there is mucus, pus, or undigested food; inquire about jaundice and whether it is intermittent or persistent; inquire about the color of urine.

Urinary System

Inquire about low back pain, frequency of urination, urgency, dysuria, hematuria, pyuria, oliguria, and nocturia. Inquire about edema, including its location, severity, and timing; inquire about abdominal pain, including its location, and whether there is any radiation of pain or interruption of urine flow. Inquire about anemia and its characteristics. Inquire about any past history of throat pain, hypertension, or bleeding.

Hematological System

Inquire about dizziness, pallor of the skin and mucous membranes, weakness, etc. Inquire about bleeding, bruising, jaundice, edema, fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Inquire about any history of drug poisoning, allergies, exposure to radioactive substances, and long-term habitual medication.

Metabolic and Endocrine System

Inquire about cold intolerance, heat intolerance, excessive sweating, fatigue, palpitations, polydipsia, polyphagia, polyuria, and edema. Inquire about muscle tremors and spasms. Inquire about abnormalities and changes in the development of sexual organs, bones, thyroid, weight, skin, hair, personality, intelligence, and physique. Inquire about any injuries, surgeries, or postpartum hemorrhage. Inquire about the health status of relatives.

Nervous System

Inquire about headaches, including their location, nature, timing, and whether they are progressively worsening. Inquire about insomnia, consciousness disturbances, memory loss, fainting, seizures, spasms, paralysis, sensory abnormalities, motor abnormalities, and personality changes.

Musculoskeletal System

Inquire about joint swelling, pain, deformity, and whether movement is restricted. Inquire about muscle numbness, atrophy, fractures, dislocations, and congenital defects. Inquire about frequent sore throats, fever, etc.

Personal History

Includes birthplace, residence, and duration of stay, especially in epidemic areas and areas with endemic diseases;

Living conditions, occupation, work environment, especially any occupational hazards;

Habits of smoking and drinking, any history of venereal diseases and syphilis, etc.

Marital History

Includes whether single or married, age at marriage, health status of the partner, marital relationship, and sexual life.

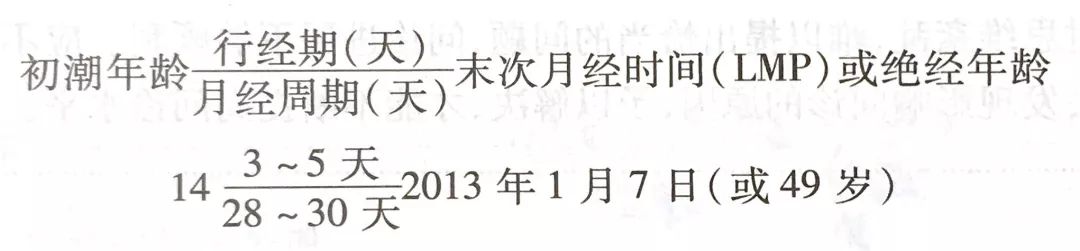

Menstrual History

Includes age of menarche, menstrual cycle and duration, menstrual volume and color, symptoms during menstruation, presence of dysmenorrhea and leukorrhea, date of last menstruation or age at menopause. For married women, inquire about the number of pregnancies, number of births, and any history of artificial or natural abortions, preterm births, or difficult deliveries. For male patients, inquire about any reproductive system diseases.

Family History

Inquire about the health and disease status of siblings, children, and parents, paying attention to whether there are any diseases similar to the patient’s, and whether there are any hereditary diseases, such as hemophilia, diabetes, mental illness, etc. Inquire about any infectious diseases. For deceased direct relatives, inquire about the cause of death and age.

Methods, Techniques, and Precautions

1. At the beginning of the consultation, due to unfamiliarity with the medical environment and fear of the disease, patients often experience anxiety. Generally, start with polite conversation, introduce yourself, and use appropriate verbal or non-verbal communication to express your willingness to alleviate the patient’s suffering. Such gestures help establish a good doctor-patient relationship, quickly shorten the distance between doctor and patient, and improve the previously unfamiliar situation, allowing for smooth collection of medical history.

2. Allow the patient to fully express and emphasize what they consider important situations and feelings. Only when the patient’s statements stray too far from the medical condition should the topic be flexibly redirected based on the main clues provided.

3. Trace the exact time of the onset of the initial symptoms up to the current evolution process. If several symptoms appear simultaneously, it is essential to determine their order of occurrence. Although it is not necessary to strictly question in the order of symptom appearance while collecting information, the obtained data should be sufficient to narrate or write the chief complaint and present illness history in chronological order.

4. Avoid suggestive questions, accusatory questions, continuous questioning, and interrogative questioning.

5. When questioning, pay attention to systematic and purposeful inquiry, sometimes using techniques like counter-questioning and explanations.

6. Avoid medical jargon; if patients use medical terms, clarify their meanings, and if patients use diagnostic terminology, record it in quotation marks.

7. Maintain a humanistic approach. Appearance, etiquette, and friendly gestures help develop a harmonious relationship with the patient, making them feel warm and approachable, even encouraging them to disclose sensitive information they initially intended to conceal.

8. If the patient provides irrelevant answers or shows poor compliance, it may be due to a lack of understanding of the doctor’s intent; check the patient’s level of understanding.

9. Pay attention to the patient. Be aware of the patient’s concerns regarding the causes, clinical symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and other issues, providing appropriate information, guidance, or education. When inquiring, offer reassurance to the patient.

Source: Jia Yi Medical School Student Affairs Office