The unpleasant bitter taste has become a significant barrier to the development of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) that urgently needs to be addressed. Powdered formulations (sàn jì) possess the flexibility of decoctions (tāng jì) in adjusting dosages according to symptoms and demonstrate good clinical efficacy. Additionally, powdered formulations require smaller dosages and are convenient to take, which can greatly eliminate the bitterness associated with decoctions. With the application of technologies such as ultra-micro powdering and particle design in TCM, the quality of powdered formulations is expected to improve significantly, potentially breaking the bottleneck of the bitter taste of effective TCM.

The bitter taste is a direct experience for individuals taking internal TCM, especially decoctions, and it hinders their clinical application to some extent. As modern people pay more attention to health, TCM has encountered a favorable opportunity for development, promoting the modernization process of TCM. However, the taste issue of TCM decoctions remains unresolved. Currently, the academic community pays far too little attention to this issue, which reflects a certain degree of neglect by practitioners regarding patients’ medication experiences. Even with accurate syndrome differentiation and precise prescriptions, if patients cannot take the medicine, diseases cannot be treated, especially for young patients or those with chronic conditions requiring long-term decoction use. The issue of the bitter taste of effective TCM should attract more attention, as it is crucial for the development of TCM. Besides adding flavor-masking or flavor-correcting agents, are there other strategies for patients taking decoctions? Based on this, this article explores how powdered formulations can address the bitter taste of TCM.

The four traditional forms of internal TCM include decoctions (tāng), powders (sàn), pills (wán), and pastes (gāo). While pills and pastes are convenient to take, their preparation requires the addition of binders or other matrices, limiting their adjustability and clinical practicality. Powdered formulations are created by grinding and mixing herbs uniformly, which are then taken with warm water, offering advantages such as smaller dosages, convenience, and faster absorption. The preparation process of powdered formulations is relatively simple, similar to that of decoctions, making it easier to adjust in clinical practice.

1. The Long History of Powdered Formulations

Powdered formulations have been recorded in ancient texts such as the “Fifty-Two Disease Formulas” and the “Huangdi Neijing” during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. For example, in the “Suwen: Discussion on Diseases,” it states: “Take ten parts of Ze Xie (Alisma) and ten parts of Bai Zhu (White Atractylodes), and mix them to form a dose the size of three fingers.” The “Shang Han Za Bing Lun,” written during the Eastern Han Dynasty, was the first to name powdered formulations, listing over thirty internal powdered formulas such as Wu Ling San (Five-Ingredient Powder), Si Ni San (Four Reverse Powder), Dang Gui Shao Yao San (Angelica and Peony Powder), Bai He Hua Shi San (Lily and Talc Powder), and Yin Chen Wu Ling San (Yin Chen and Five-Ingredient Powder), which were often taken with rice soup, warm water, or wine. For instance, the Wu Ling San formula states: “Crush the five ingredients into a powder, mix with white drink and take a spoonful three times a day,” where white drink refers to rice soup. Powdered formulations can also be decocted like decoctions without needing to be filtered. In the “Shang Han Lun,” it is noted that for the Si Ni San formula, adjustments can be made: “For those with diarrhea and heavy stools, first boil three sheng of Xie Bai (Garlic) in five liters of water… then take a spoonful of the powder in the decoction, boil down to one and a half sheng, and take warm in two doses.” Decocting powdered formulations into a soup makes their application more flexible. However, powdered formulations require manual grinding, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and their hygroscopic nature makes them prone to spoilage, significantly limiting their application. By the early Song Dynasty, due to a shortage of medicinal materials, powdered formulations rapidly developed to save on herbs. With confirmed clinical efficacy and mature preparation techniques, along with government support, powdered formulations gradually reached their peak during the Song Dynasty. As noted by Shen Kuo in the “Mengxi Bitan”: “In recent times, the use of decoctions has become rare; all prescriptions are made into powders.” During this period, the government officially compiled the “Taiping Huimin Heji Ju Fang,” which included 788 formulas, of which 239 were powdered formulations.

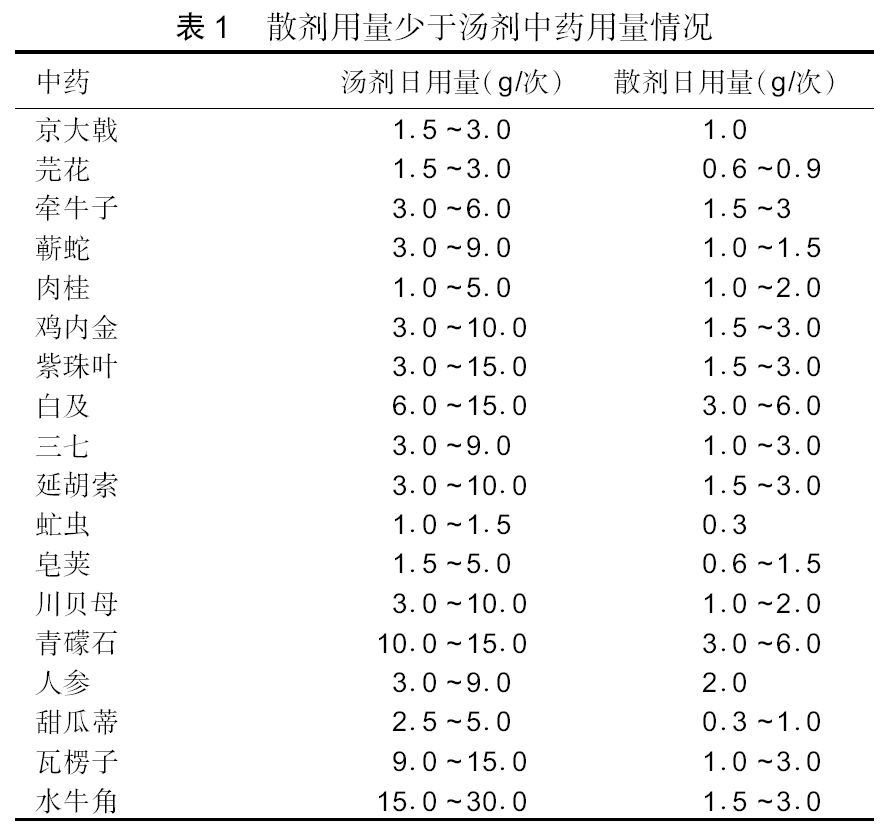

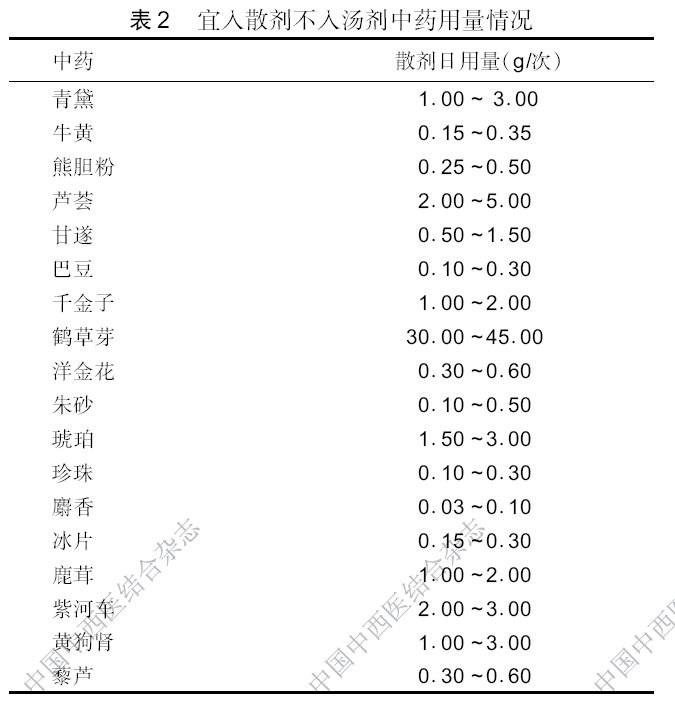

Over the centuries, the application of powdered formulations in TCM has accumulated rich experience. The dosage range for most powdered formulations is consistent with that of decoctions, such as Chi Shao (Red Peony), Long Dan Cao (Gentian), Ma Bo (Mushroom), Fang Feng (Siler), Cang Er Zi (Xanthium), Niu Bang Zi (Burdock), and Chan Tui (Cicada Slough); some powdered formulations have lower dosages than decoctions, primarily consisting of precious, potent, or shell-stone herbs (Table 1); and there are also some herbs that are more suitable for powdered formulations than decoctions, often being precious or potent herbs (Table 2).

2. The Efficacy of Powdered Formulations is Not Inferior to Decoctions

Although the dosage is less than that of decoctions, the efficacy is not inferior. As modern scholar Zhang Taiyan commented, “Although the quantity is light, the effect is nearly the same; this is the clever use of it.” Many scholars have also conducted research on the efficacy of powdered formulations. Che Xiangqing and others compared the anti-inflammatory effects of Bai Hu Tang (White Tiger Decoction) in decoction and powdered form, finding that the anti-inflammatory effect of the powdered group was the same as that of the decoction group but with a smaller dosage, with statistically significant differences. Zou Benliang and others used Xiao Yao San (Free and Easy Wanderer Powder) in both decoction and powdered forms to treat liver qi stagnation and spleen deficiency syndrome, discovering that the powdered formulation was superior in improving TCM symptom scores and symptoms of loose stools. Wang Junli and others found that the analgesic effect of Ling Zi San (Lingzi Powder) was superior in powdered form compared to decoction. Sun Caixia and others detected differences in the chemical composition of Wu Ling San when converted from powdered to decoction, finding that this could lead to the loss of the main active ingredients. Xiong Ping and others compared the anti-ulcer effects of Zuo Jin Wan (Left Metal Pill) in water decoction and powdered form, discovering that the powdered formulation was superior in anti-ulcer effects in rats. In the water decoction of Wu Zhu Yu (Evodia) and Huang Lian (Coptis), the dissolution rates of berberine in Huang Lian and flavonoids in Wu Zhu Yu were reduced, and since the water decoction empties quickly in the gastrointestinal tract, the local effect time is short; whereas powdered formulations have a relatively longer gastrointestinal emptying time, allowing the fine powder to easily adhere to the gastrointestinal mucosa, keeping the damaged mucosa and submucosal tissue in a high-concentration medicinal solution for a longer time, demonstrating the therapeutic advantages of powdered formulations.

3. The Taste Advantage of Powdered Formulations

Compared to decoctions, the taste advantage of powdered formulations mainly stems from their smaller dosage. The “predecessor” of powdered formulations is also the medicinal slices used in decoctions, which are further processed into powder. After grinding, the surface area of the herbs significantly increases, making the effective components easier to extract; thus, the dosage of powdered formulations is significantly reduced compared to decoctions. Cai Guangxian and others collected over 400 prescriptions from more than 40 important medical texts from the Song to Qing Dynasties, such as “Huimin Heji Ju Fang,” “Taiping Shenghui Fang,” “Zheng Zhi Zhun Sheng,” and “Jing Yue Quan Shu,” and conducted a comparative study on the dosages of 28 commonly used medicinal slices in decoctions and powdered formulations, finding that the dosages of these herbs in powdered formulations were significantly reduced, approximately 1/3 to 1/5 of the decoction dosage. As seen in Table 1, the dosage of the same herb in decoction can be up to 20 times that of the powdered formulation, averaging about 4.1 times. In the “Shang Han Za Bing Lun,” it is recorded that the single dosage of powdered formulations can be as little as “half a qian (a traditional weight unit)” and as much as “one fangcun (a traditional measurement unit),” which is approximately 1-2 grams today. The smaller dosage can effectively alleviate the bitter taste, and when taken with a small amount of honey or sugar water, the taste can be further improved. Therefore, powdered formulations avoid the discomfort of taking bitter decoctions, greatly enhancing clinical medication compliance.

4. The Modern Development of Powdered Formulations

In the 1990s, with the introduction of ultra-micro powder technology in the field of TCM processing, ultra-micro medicinal slices were produced, further promoting the clinical application of TCM powdered formulations. Ultra-micro medicinal slices are a new type of TCM slice made by grinding herbs into ultra-fine powder (particle size <75 μm) without altering their chemical structure, aiming to break the cell walls of the herbs. The dissolution and absorption of the components in ultra-micro medicinal slices are higher than those of traditional slices and powdered formulations, which can further reduce the prescribed dosage while improving the bioavailability of the effective components. Additionally, they have controllable quality and reliable efficacy, facilitating large-scale industrial production, making it a hot topic in recent TCM modernization research. Ning Lili and others found that when the dosage of ultra-micro medicinal slices of Liu Wei Di Huang Wan (Six-Ingredient Rehmannia Pill) was 1/3 of that of fine powder, the efficacy in anti-fatigue, hypoxia tolerance, and blood sugar reduction was the same.

In recent years, the emerging technology of TCM particle design has developed based on ultra-micro powdering technology. After TCM is ground, the specific surface area increases the surface free energy of the powder, making it prone to agglomeration, leading to uneven dispersion and unstable quality. Particle design technology involves structural and functional design of the powder at the microscopic level based on its physicochemical properties, thereby improving its performance. This technology can achieve uniform dispersion and stability of TCM preparations by controlling the order of powdering and utilizing different powders to form specific structures and functions. Furthermore, by selecting TCM shell particles or composite particles for the outer layer, powdered formulations can present different flavors; for example, arranging licorice particles on the outer layer can make the powder taste sweeter, while arranging bitter or astringent particles in the inner layer can effectively improve the taste of the powdered formulation. Through TCM particle design technology, volatile components can be effectively protected, the dissolution of poorly soluble components can be improved, and the hygroscopicity of the powder can be reduced. The installation of automated capsule machines in hospitals can further improve taste by mixing powdered herbs and encapsulating them after clinical prescriptions. However, the widespread clinical application of ultra-micro powdering and particle design in TCM still requires extensive research in areas such as the consistency of clinical efficacy, selection and improvement of processing equipment, standardization and control of processing procedures, and determination of dosages.

Currently, widely used granules that do not require decoction can be flexibly adjusted according to clinical conditions, have stable quality, confirmed efficacy, are easy to carry, and are convenient to take, occupying a certain market share in clinical applications. They are also widely used in countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, with increasing competition in the international market. However, these granules still require the addition of a certain amount of hot water to become decoctions, which does not avoid the issue of bitterness; some larger granules are difficult to dissolve when taken, leading to sedimentation and even worse taste than decoctions. Moreover, these formula granules only contain part of the original slices and not all components, and whether they retain the original efficacy for different conditions still requires broader and stricter clinical validation.

This article focuses on how powdered formulations can address the bitter taste of TCM, hoping to draw attention from the academic community to jointly seek effective solutions to this issue. This requires close cooperation between clinical and basic research, as well as collaborative efforts across multiple disciplines.

Click to read the original text and download the full article