In 1982, while I was in high school, the movie “Shaolin Temple” starring Jet Li became a nationwide sensation. The government, scientists, and military personnel all expressed their approval of martial arts and qigong, sparking a near-nationwide craze for practicing qigong and martial arts. I was no exception and was swept up in it.

The spirit of chivalry and righteousness locked in my dreams. A few friends and I began to train hard like the monks in the movie, waking up every day at five to run five kilometers, then doing push-ups, sit-ups, horse stance, and practicing various martial arts techniques. We would even tie sandbags to our legs and hop up steep steps, and I had a stone lock and stone barbell made by a stonemason to train my arm strength. I would lie back on a grinding wheel to do sit-ups, and practice hanging from a high bar to touch my toes…

Not satisfied, I sought out local martial arts masters and earnestly apprenticed with them to learn hard qigong, iron sand palm, Shaolin Hong Quan, Luohan Quan, drunken boxing, military boxing, and free fighting… Influenced by Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do, I would hang over ten kilograms on my head every day to strengthen my neck. Inspired by the movie “Eagle Claw Iron Shirt”, I practiced three-finger and two-finger push-ups, and used my fingers to grip a jar filled with sand to practice Eagle Claw technique, aiming to tear my opponent’s tendons and flesh in combat. After watching “Iron Bridge Three”, I would strike trees with my forearms…

After years of hard training, my physical fitness improved significantly. At that time, I was 1.72 meters tall and weighed over 120 pounds. I could jump up seven or eight steps of a concrete staircase from a standstill and lift a 100-pound stone barbell over ten times with one hand. During sparring, I often made my opponents bleed from their noses and mouths, and in free fighting, my kicks would leave bruises on their thighs. At my best, I could tense my thigh muscles so hard that others couldn’t even pinch my skin with their nails.

However, one night in 1986, while drinking beer with a few martial arts friends at a roadside shop, we had a conflict with two local thugs. Naturally, they were no match for us martial artists and fled. We continued to drink, feeling victorious. But moments later, the thugs returned with a group, brandishing gleaming knives and charging at us. We were caught off guard, unarmed, and two of us were soon slashed, blood spraying everywhere. One of them had a family background in martial arts, and I was so scared that I froze, forgetting all the techniques I had practiced. Fortunately, I reacted quickly enough to dodge the knife aimed at me and ran away…

After this battle, I, who had escaped unscathed, suddenly realized: the human body ultimately cannot withstand a knife!

Then, I gradually discovered that humans seem to share a common tendency: revenge. This is a vicious cycle; if one is injured, they will seek revenge once healed; if a loved one is killed, they will spend their lives seeking vengeance. Many people practice martial arts primarily to defend against bullying, to confront enemies, and to seek revenge. If they are retaliated against, they must seek revenge again, sharpening their knives, believing that a gentleman’s revenge is never too late…

From then on, I pondered: for someone to become a martial arts master, they must have defeated, injured, or even killed some opponents. The injured will seek revenge once healed, and the descendants of the deceased will also wait for their chance. To deal with increasingly powerful avengers, masters must either train harder or ally with dark forces. But how do they deal with ambushes and attacks? Do they have to live like characters in movies, always alert? Otherwise, after thirty years of martial arts training, if one is killed in a fight, what is the meaning of their training?

When will the cycle of revenge end? How can one defeat an opponent without provoking revenge? What is true martial prowess? Many say that true masters rarely show themselves, and I believe there are indeed true masters. Is it really about mastering invulnerable skills that completely crush opponents, allowing one to reign supreme? But if one reaches that height, why hide in the mountains? There are always stronger people out there; when does one truly become a master?

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, I encountered countless masters from Buddhism, Taoism, and folk traditions, as well as their health-preserving techniques, such as breaking bricks with one hand, breaking steel rods with feet, smashing stones with the abdomen, and various other extraordinary skills… People were infatuated with these, while I wandered among them, seeking the truth behind these practices.

In fact, I was fortunate. I had already seen through many deceptive techniques by the 1980s. From the early 1980s martial arts and qigong craze to the late 1990s, various martial arts and qigong farces gradually faded. I witnessed the entire process, which laid a solid foundation for my later studies in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), enabling me to discern and not be easily fooled by masters.

In 1998, during my search, I met Master Chen Hegao and was introduced to the concept of unrestricted fighting. It was then that I began to realize that true martial arts do not primarily depend on techniques and skills. Once a certain physical foundation is established, there is no need to delve deeper into flashy techniques; what is more important is to enhance one’s spirit and resolve. There are no fixed methods, but all methods must adhere to the law. Martial arts are about stopping conflict, which means incapacitating the opponent’s ability to resist under the premise of self-defense, which is the true essence of martial arts.

I thought of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Japan, so arrogant during World War II, was ultimately brought to its knees by the atomic bomb from America, and from then on, they obeyed the U.S. without daring to retaliate. True martial prowess not only defeats the enemy but also eliminates their capacity for revenge. The techniques practiced by martial artists, competing for superiority, are essentially just performances with little practical significance. Using force to resolve interpersonal conflicts in real life is foolish.

In 1999, while I was in business, although the concept of unrestricted fighting greatly influenced me, I was still somewhat confused about traditional martial arts. One day, my elderly mother suffered from lumbar disc herniation, enduring unbearable pain in all positions. After visiting numerous hospitals and clinics with no effective treatment or being advised to undergo surgery, I encountered a blind masseur. After more than two months of therapy, my mother’s symptoms significantly improved. Although it was only a noticeable improvement, it amazed me, prompting me to self-study TCM, and thus I entered the world of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

As a TCM enthusiast, I became fascinated by various miraculous folk medical legends I heard, and my stubborn pursuit of martial arts mastery shifted to medicine. I sought out TCM masters, attending thirty to forty different training courses in various techniques, meeting many like-minded individuals, and visiting some folk medical experts across the country. I also developed a strong interest in more mysterious practices such as talismans, spells, and necromancy.

I experienced the spell of bone transformation, where a bamboo chopstick was broken into four pieces and tossed into a bowl of water. After the master recited the incantation, I drank it down without discomfort. However, another hesitant classmate struggled, choking on the pieces and ending up in tears…

After learning spells, I would burn yellow paper with symbols to change interpersonal relationships while drinking, secretly reciting incantations to make the liquor disappear, allowing me to drink without getting drunk. Using spells, I could strike at the stars in the sky, making them sway… Isn’t that amusing and absurd? Haha, there are quite a few believers in such folk practices, and sometimes they really do seem to work.

I also experienced necromancy, where a medium could summon deceased relatives to converse with you. A stranger medium could describe your relationship with the deceased in detail, their expressions, tones, and events, just like when they were alive…

In addition to exploring more truths about life, I also became interested in fortune-telling, feng shui, and predictions, leading me to visit and experience many masters of the I Ching and feng shui, as well as various folk shamans. From disbelief to half-belief to firm belief, then back to disbelief, and finally to self-confidence, I ended up laughing at it all. This process fully demonstrated the four words of belief, understanding, practice, and verification, reflecting my increasing awareness.

After more than a decade of ups and downs in the TCM field, I gradually understood that some of the deceptive techniques popular in the qigong and martial arts community in the 1980s did not disappear in China but transformed into other forms, now fervently prevalent in the medical and health fields. Most practitioners in the medical field, like the martial artists of the past, have diligently practiced various medical techniques, battling diseases in countless rounds, achieving narrow victories, and seeing symptoms disappear, earning the title of miraculous doctor. Little do they know, the diseases they defeated do not concede, continuing to breed in the shadows, waiting for their chance to retaliate. Once the timing is right, old ailments resurface or manifest in another form, leaving the practitioners helpless to defend against the consequences of chronic illnesses, which the patients must endure.

Just as I reflected on the meaning of martial arts at the end of the 1980s, I found myself pondering the significance of practicing medicine. In my medical practice, I employed acupuncture, herbal medicine, massage, moxibustion, hot compresses, gua sha, and cupping, but those ailments seemed like defeated enemies, either resting for a while before retaliating or continuing to cause harm in different forms, leaving me increasingly perplexed… Not only I felt this way, but most other practitioners around me did too. The practice of medicine was exhausting, and I found myself questioning the meaning of my medical journey.

Gradually, I began to understand why ancient people combined the concepts of immortal medicine and fate in treating diseases. Every medical technique has its limitations, and some issues must be resolved with the help of other energies. Just as no matter how powerful one’s fists and feet are, sometimes one must rely on sticks, knives, and guns, as well as strategies and timing, to solve problems smoothly. The relationship between medicine and disease is also a form of “martial” relationship. How many practical problems can a martial artist’s flashy techniques solve? So, how should a practitioner combat disease? Relying solely on acupuncture, herbal medicine, and massage can indeed inflict pain and drive away diseases to some extent, but once the disease regains strength, it will continue to harm.

What the unrestricted fighting concept taught me was that within legal limits, if you can kill the enemy, do not merely injure them; if you can injure them, do not merely cause light wounds; if you can cause heavy wounds, do not cause light ones; otherwise, you will face endless ambushes and retaliation. So, what should I truly focus on in the field of medicine?

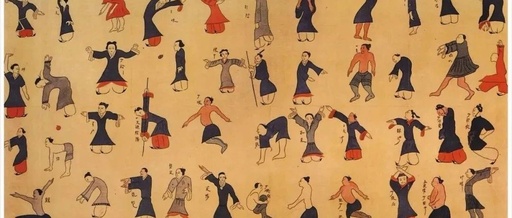

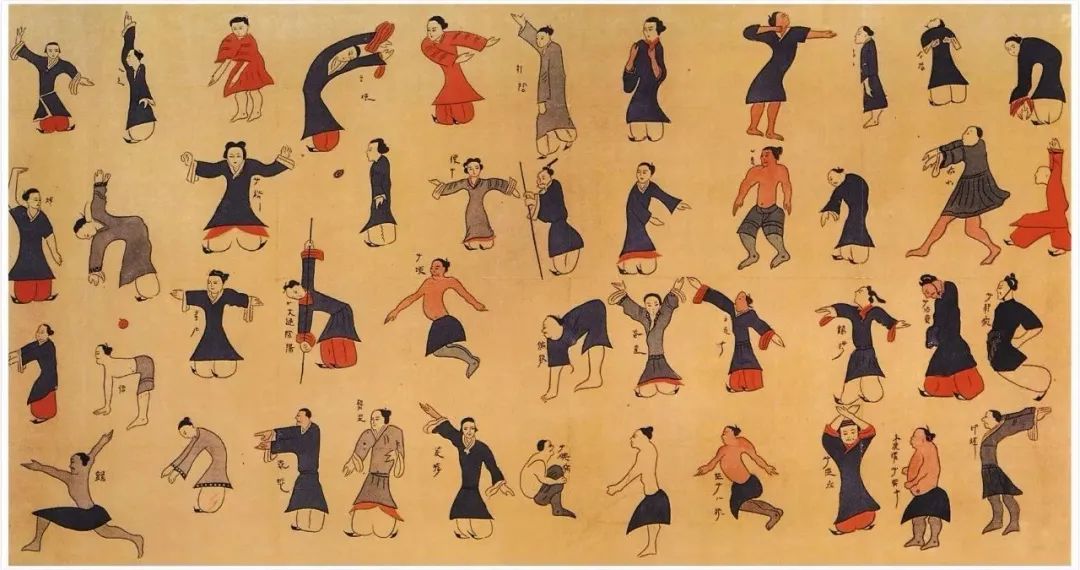

I have always enjoyed exercising, and after entering the TCM field, I did not give up on training; I just shifted my focus to studying health preservation and disease treatment. During this process, I encountered methods such as the Five Animal Frolics, Ba Duan Jin, Yi Jin Jing, Ma Wang Dui guiding techniques, and Hong Yuan Gong of Tong Bei Quan. The most influential for me was the Hong Yuan Gong taught by Master Wang Hongjun, along with the guiding diagrams and breathing methods discovered through archaeological research on the Ma Wang Dui tomb.

I met Master Wang Hongjun in 2008, and I was amazed that he could allow anyone to kick him in the groin without flinching. After observing him closely, I greatly admired him. The Hong Yuan Gong he taught combined guiding techniques with breathing, but Master Wang was not well-educated and could only teach the techniques without explaining the theory behind them. This left me wanting more, so I deliberately sought out materials on breathing and guiding techniques, leading me to the guiding diagrams and breathing methods unearthed from the Ma Wang Dui tomb in 1974.

However, the popular Ma Wang Dui guiding techniques for health preservation did not seem quite right to me. The ancient understanding of life over two thousand years ago was certainly not as modern, but it should not be superficial either. I once searched online and purchased some silk manuscripts related to the eleven meridians of the feet and arms and guiding techniques unearthed from the Ma Wang Dui tomb, but I could not understand the original text at all. When I looked at the experts’ annotations, I felt somewhat skeptical but did not know how to truly understand or practice them, leaving me quite helpless.

As I integrated various acupuncture techniques from both TCM and Western medicine, in 2012, after gaining a preliminary understanding of the “Huang Di Nei Jing”, I gradually developed a series of clinical application methods for the nine needles mentioned in the Nei Jing and combined several of them to create the “Li Xin Seven Needles”. From then on, I immersed myself in the “Huang Di Nei Jing”, thinking and researching all day, losing interest in learning from anyone else.

What truly benefited me was Master Wang Hongjun’s saying, “When the qi is sufficient, one can strike without moving.” In the first few years, I did not understand what he meant, only knowing that ordinary people could not harm him; punches against him felt like hitting a rock, causing pain to the attacker. As I delved deeper into the experience and understanding of Hong Yuan Gong, influenced by the “Huang Di Nei Jing”, I gradually realized that the qi Master Wang referred to should be the body’s Wei Qi, which sparked my strong interest in researching “Wei Qi”.

However, at that time, I searched the medical community and found that apart from the “Huang Di Nei Jing”, which discussed Wei Qi in detail, I could not find any clearer explanations from other sources. Practitioners from the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, Qing dynasties, and contemporary doctors all seemed to follow the previous explanations without elaborating. It seemed that only the ancients understood Wei Qi better.

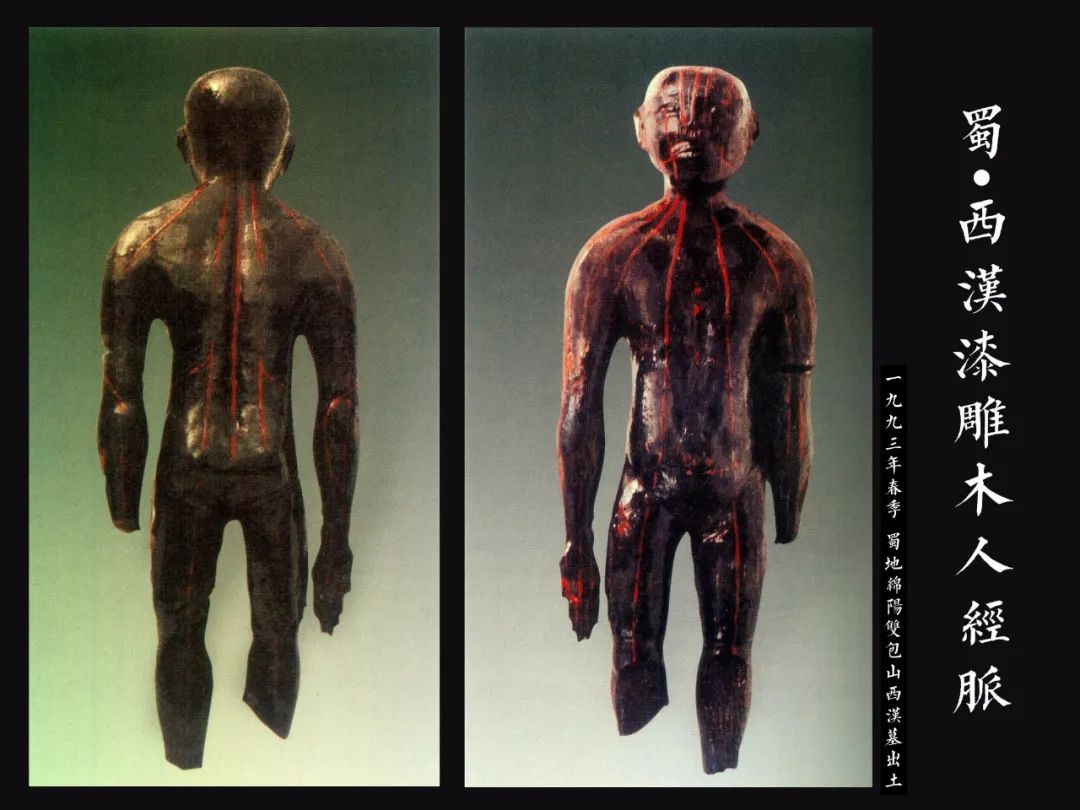

At this time, news came of the discovery of human figurines with meridians from the Han tomb at Laoguan Mountain in Chengdu. I quickly searched for related materials and saw that in the Chengdu Museum, human figurines with painted meridians were also unearthed from the Mianyang Shuangbao Mountain Han tomb in the 1990s. Comparing the images of the two figurines, I was overjoyed to find that the meridian lines on the Laoguan Mountain figurine closely resembled the distribution of the twelve meridians in the Nei Jing; while the meridian lines on the Shuangbao Mountain figurine were remarkably similar to the pathways of Wei Qi described in the Nei Jing, which deepened my understanding of the circulation of Wei Qi in the human body.

Turning back to the Ma Wang Dui tomb’s “Eleven Meridians of the Feet and Arms”, it seems to reflect the ancient understanding of the circulation of Wei Qi rather than the traditional meridians, which further solidified my research on Wei Qi.

In May 2015, in the auditorium of Nanfang Hospital in Guangdong, I could no longer contain my joy and shared some of the truths I had grasped about Wei Qi with my students. However, the concepts of Ying Qi, Wei Qi, Yin Yang, the four seasons, and the five elements left everyone confused, not understanding what I was saying. Some students who had previously recognized my acupuncture techniques began to feel that I was becoming increasingly esoteric and disconnected from reality.

Gradually, I felt increasingly isolated on the path of the Nei Jing. However, the stubbornness developed from years of martial arts training made me unwilling to give up, so I continued to think and research, even amidst internal and external challenges, feeling physically and mentally exhausted.

Until the summer of 2019, after developing the “Qi Jiao Moxibustion” series, I suddenly realized that after immersing myself in the Nei Jing for so many years, I could actually understand the significance of the Ma Wang Dui guiding diagrams. It seemed that the ancients had connected the foundational elements of human life mentioned in the Nei Jing, such as Wei Qi, Jing Jin, San Jiao, Gao Huang, Ming Men, Qi Jie, Zong Jin, Kai He Shu, and Ben Gen, together.

Items buried with the deceased must have been highly valued by them during their lifetime. The guiding diagram from the Ma Wang Dui tomb is significant enough to warrant burial. Everyone exercises, and the actions depicted in the diagram can be easily performed by ordinary people. If we merely mimic these movements without understanding their significance, we will not grasp what makes them special, nor will we comprehend why the tomb owner chose to be buried with the guiding diagram.

The guiding diagram was unearthed painted on silk, and the front of the silk also contained the texts “Eleven Meridians of the Feet and Arms” and “Que Gu Shi Qi Pian”, forming a single scroll. This is intriguing; why write these specific texts? I must first understand the meanings of those two texts to comprehend the guiding diagram.

After purchasing relevant archaeological literature, in-depth research revealed that the “Eleven Meridians of the Feet and Arms” actually discusses the circulation of Wei Qi in the human body, which aligns with the saying in the Ma Wang Dui medical texts, “The path of Qi must reach the extremities, where essence is generated but does not exit.” The “Que Gu Shi Qi” discusses breathing methods, especially the phrase “The breath of food is exhaled and inhaled, beginning with lying down and rising; during exhalation, one breathes in and blows out.”

In ancient texts, we find that the practice of guiding Qi was very popular two to three thousand years ago. For example, in the “Zhuangzi, Outer Chapters, Ke Yi”, it states: “Breathing in and out, exhaling the old and inhaling the new, imitating the movements of bears and birds, is for longevity.” People practiced guiding techniques combined with breathing to prolong life. In the late Han dynasty, Hua Tuo specifically created the Five Animal Frolics, imitating the movements of tigers, deer, bears, monkeys, and birds, which had excellent health benefits.

I personally believe that the guiding techniques of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods likely also incorporated breathing and massage, as the combination of these three methods would be more beneficial for health.

It is well known that the “Huang Di Nei Jing” is difficult to understand; in fact, the medical texts from the Ma Wang Dui tomb are even more obscure. From the content, it appears that the medical texts unearthed from Ma Wang Dui were likely written before the Nei Jing was compiled. Therefore, I believe that to understand the Ma Wang Dui guiding techniques, one must first grasp the foundational knowledge in the “Huang Di Nei Jing”, such as how Wei Qi circulates, the distribution of Gao Huang, and the significance of Ben Gen…

At this point in my research, the guiding diagram unearthed from the Ma Wang Dui tomb can be utilized. By referencing the guiding diagram, combining it with the understanding of the Nei Jing, and inspired by Hong Yuan Gong, I developed the “Gao Huang Gong” and “Ben Gen Gong”.

How to practice? For guiding Qi, the key is to perform movements gently and breathe slowly, deeply, and steadily. However, Gao Huang Gong and Ben Gen Gong have specific requirements; either a knowledgeable person must guide you step by step, correcting mistakes in real-time, or you must understand the foundational knowledge of the Nei Jing, such as Wei Qi, Jing Jin, San Jiao, Gao Huang, Ming Men, Qi Jie, Zong Jin, Kai He Shu, and Ben Gen. Once you truly understand these, your body will naturally know how to practice Gao Huang and Ben Gen during breathing and guiding. Because you will be clear about the pathways and distribution of Qi, your body will instinctively seek the right sensations and movements. If you do not understand the essence and merely mimic my movements rigidly, you are likely to faint or injure yourself.

This is not an exaggeration; during the early stages of my development, I nearly fainted several times. Two students who had been following me also experienced blackouts during their initial practice, waking up dazed on the ground. They had studied the foundational knowledge of the Nei Jing with me for several years, but they still habitually relied on brute strength to mimic the movements, resulting in fainting after just a few attempts.

What are the effects?

For me, the benefits have been extraordinary. Due to years of dedicated research, coupled with emotional distress and neglecting self-care, I suffered a stroke in 2015, resulting in left-sided hemiplegia. Although I recovered significantly with timely adjustments, I still experienced residual numbness and weakness in my left hand and foot. In the following years, I fell into a state of internal and external troubles, and by 2019 to 2020, my health had deteriorated significantly: chronic sleep issues, a sharp decline in sexual function, frequent palpitations, blood pressure consistently around 170-180, difficulty walking, uneven shoulders, rough skin with large pores on my back, and frequent bumps. Climbing stairs left me breathless, and I would turn pale with exertion.

At that time, a friend jokingly pushed me lightly on my back, and I could only run four or five steps before stopping; otherwise, I would fall. My condition was worse than that of a sixty or seventy-year-old, and as someone studying the Nei Jing, I often felt embarrassed.

Isn’t it a bit contradictory? Since I possess such excellent methods and high understanding, why not adjust my own health? Well, there are reasons for my poor condition. On one hand, I had just experienced the sadness of betrayal and was often in a state of anxiety, needing to delve deeply into research while managing various affairs, leaving me unable to focus on self-care. On the other hand, I was overconfident in my understanding, thinking that I could easily restore my health whenever it deteriorated, so I intended to wait until my condition was as bad as possible before making adjustments.

In the Spring Festival of 2021, affected by the pandemic, I was not doing well, and my health continued to decline. I finally decided to reduce my focus on research and development and dedicate some time to self-care. I also wanted to prove to those around me that my confidence was genuine, showing them how quickly I could recover from such a poor state. On the sixth day of the Lunar New Year, I began to consistently practice breathing and guiding techniques, as well as Gao Huang Gong and Ben Gen Gong, training six days a week with one day of rest. After six months, my health improved significantly.

In the first two months of training, my body rapidly became leaner and firmer, and my waist size decreased, but I only lost a few pounds. After two months, my weight began to drop noticeably, and by the fourth month, my weight decreased from over 170 pounds to 140 pounds. For the next two months, my weight stabilized at 150 pounds, regardless of how much I sweated or how little I ate.

However, the various discomforts I had experienced disappeared without a trace after three months. I could walk up and down stairs without feeling weak, my skin became smooth, and the large pores on my back shrank. After six months of practice, my stability improved significantly, and I felt a strong sense of energy in my hands and feet. My arms became soft as cotton yet strong as iron. My mental state was especially good; I only needed three to five hours of sleep each night, yet I felt clear-headed and refreshed. The whites of my eyes became increasingly bright, and I managed a large volume of work without feeling fatigued. Although I was already a fifty-five-year-old man, I felt as if I had returned to the physical state of my thirties, which was fantastic!

In terms of diet, I did not restrict myself or fast during the entire process. I made sure to supplement various nutrients daily, including pork, beef, chicken, duck, goose, rabbit, pigeon, fish, and various eggs, prepared in steaming, frying, boiling, and roasting methods, along with seasonal vegetables and fruits.

As the saying goes, “Those who are not alone will have neighbors.” Several friends and students who interacted closely with me witnessed my significant changes in just one or two months, and many began to practice guiding Qi alongside me. Some students who had previously been inattentive during my Hong Yuan Gong teachings became focused on practicing Gao Huang Gong and Ben Gen Gong after witnessing my results. After one or two months of practice, they experienced significant changes in their bodies: improved physique, increased energy, smoother skin, more flexible limbs, and greater strength.

Ancient sages, truly do not deceive me!

The “Huang Di Nei Jing” indeed contains invaluable treasures, but most who see it are blind to its worth. Why? It is quite normal; just as many people know you in this world, very few truly understand you.