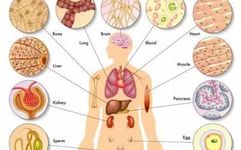

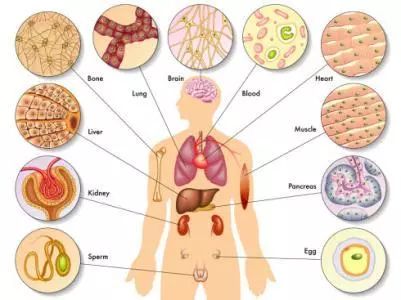

The six fu organs refer to the gallbladder, stomach, large intestine, small intestine, bladder, and san jiao (triple burner). Except for the gallbladder, all are involved in the intake and transportation of food and fluids, and are responsible for the separation of clear and turbid substances. Their function is to “excrete without storing,” corresponding and cooperating with the five zang organs. The five zang organs are yin and located internally, while the six fu organs are yang and located externally, together maintaining the life activities of the human body.

The gallbladder is located beneath the liver and was referred to by ancient people as the “palace of clarity.” It stores clear bile, which is secreted to aid in the digestion of food. It works in conjunction with the liver, forming an interdependent relationship. The liver governs planning and the gallbladder governs decision-making, which falls within the realm of mental activities. Common phrases such as “courageous” and “timid as a mouse” relate to the strength of gallbladder qi.

The stomach is responsible for receiving and rotting food and fluids, meaning it accommodates and digests ingested substances. It works in conjunction with the spleen, collectively referred to as the “official of granaries,” similar to a warehouse that stores food and supplies the body’s nutritional needs. Thus, the spleen and stomach are often called the “foundation of postnatal life,” with the stomach alone referred to as the “sea of food and fluids.”

The small intestine receives and digests food, separating the clear from the turbid. It extracts the pure essence (nutrients) to be stored in the five zang organs and the turbid waste (food residues or waste-containing fluids) to be expelled through the six fu organs (mainly the large intestine and bladder). Therefore, the small intestine is referred to as the “official of reception and storage,” and it has an interdependent relationship with the heart.

The large intestine is known as the “official of conduction.” “Conduction” refers to the process of transportation, and its main function is to transport the residues and waste from the small intestine out of the body. It works in conjunction with the lungs, forming an interdependent relationship. Since the lungs store the po (corporeal soul), the ancient people referred to the anus at the end of the large intestine as the “gate of po.”

The bladder is located in the lower abdomen and was referred to as the “official of the capital.” The term “capital” refers to a place where water and fluids accumulate, indicating that the bladder is the storage place for urine. Its main function is to store fluids and expel urine. It works in conjunction with the kidneys, forming an interdependent relationship.

Among the six fu organs, the five mentioned above are well-known, but the san jiao is less commonly understood. Indeed, it is quite difficult to pinpoint its specific location and form. The nature of this organ has been the subject of much discussion among ancient scholars, and we will not enumerate them all here. We can consider it as a functional unit. According to the explanations in the Neijing, the san jiao encompasses all the locations of the five zang and six fu organs, and its function relates to the overall functionality of the organs. It is divided into upper, middle, and lower jiao, which summarize the physiological functions and pathological changes of the internal organs in the chest, stomach, and lower abdomen, respectively. Specifically, the “upper jiao is like mist,” representing the heart and lungs’ function of circulating qi and blood; the “middle jiao is like a stew,” representing the spleen and stomach’s function of digesting and processing food; and the “lower jiao is like a drain,” representing the bladder and large intestine’s function of expelling waste.