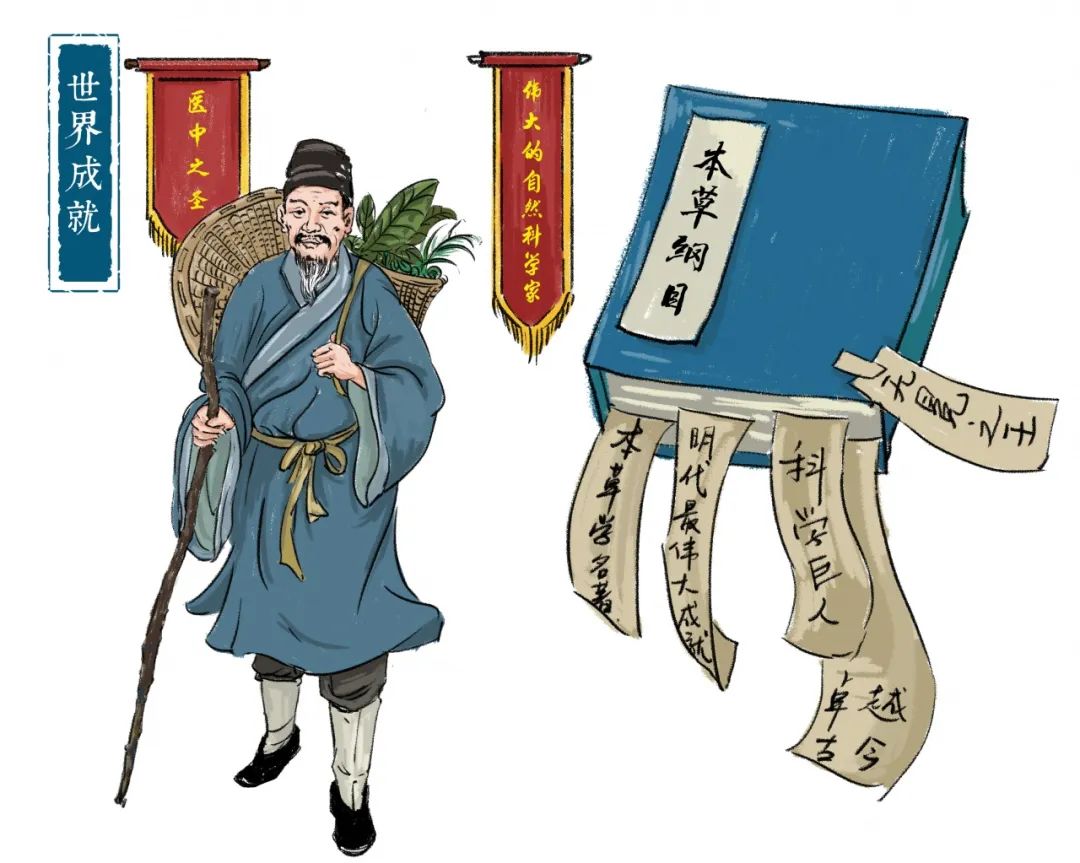

In the current battle against the COVID-19 pandemic in China, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has played a significant role. The TCM classic, the Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica), compiled over 500 years ago, documented many effective methods for disaster and epidemic prevention.

In terms of air disinfection, burning substances such as Chen Xiang (Agarwood), Mi Xiang (Honey Fragrance), Tan Xiang (Sandalwood), Jiang Zhen Xiang (Incense), and An Xiang (Benzoin) can have epidemic-preventing effects. For high-temperature steaming and disinfection, “When the epidemic strikes, take the clothes of the initial patient and steam them in a pot, then the whole family will not be infected.”[1] Steaming contaminated clothing at high temperatures to prevent further infection is also a very scientific method by today’s standards.In terms of medicinal baths for disinfection, using a decoction of Bai Mao Xiang (Imperata cylindrica), Mao Xiang (Acorus calamus), and Lan Cao (Orchid grass) for bathing can dispel epidemic qi. In terms of medicinal prevention of epidemics, the Ben Cao Gang Mu has a dedicated section on epidemic treatment, compiling numerous prescriptions for epidemic prevention, such as Cang Er Zi (Xanthium) taken in powder form with water to dispel evil, Tao Ren (Peach Kernel) and Zhu Yu (Evodia) stir-fried with salt to chew for preventing pestilence, and garlic juice to treat seasonal febrile diseases, among others.In terms of water disinfection, Li Shizhen believed that “water is the source of all transformations,” and the quality of water is crucial for human health. Water from ditches near cities is often polluted; if it must be used, it should be boiled and allowed to settle for an hour before drinking.[2] However, many people are unaware that the publication process of the Ben Cao Gang Mu was fraught with difficulties. It is said that the great literary figure Wang Shizhen was the one who recognized the value of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, as his preface referred to it as “the secret record of emperors and a treasure for the people.” Yet, few know that Li Shizhen had sought a preface from Wang ten years prior, but to no avail… Others say that the bookseller Hu Chenglong recognized the true value of the work, allowing the Ben Cao Gang Mu to be immortalized in history. But why did it take six years for the book to be engraved and printed? Alas, Li Shizhen passed away in the third year of waiting for publication in Nanjing. He never saw the work that consumed his life come to fruition, nor did he anticipate that the book would receive the emperor Wanli’s personal approval, or that he would be posthumously honored as “the Saint of Medicine” and “a great natural scientist” by various circles.What is the truth of history?

► The Ben Cao Gang Mu is a monumental work in the history of TCM

1

“Repeated attempts to gain fame but failed”—— Changing to medicine after failing the imperial examinations Li Shizhen was born in the thirteenth year of the Zhengde era (1518) in a well-off family in Wuxizhou (now Qichun County, Hubei Province). His father, Li Yanwen, was a physician who had served in the Imperial Medical Institute.[3] Being selected as a consultant for the highest medical institution in the capital from a county doctor a thousand miles away was quite remarkable. Thus, the Li family was well-known locally. However, initially, Li Shizhen did not follow in his father’s footsteps but chose the path of the imperial examinations. During the Ming Dynasty, the imperial examination was a crucial way for commoners to achieve prominence, and most scholars aspired to official positions. Li Shizhen, who was passionate about studying from a young age, was no exception.[4] At the age of 14, he passed the first level of the examination but failed to succeed in the provincial examinations in Wuchang three times in the years 1534, 1537, and 1540.

► Li Shizhen, who was devoted to the official path, realized the wonders of medicine! In the summer of 1537, Li Shizhen fell seriously ill due to a cold that led to “bone steaming” (pulmonary tuberculosis). “After a month, it worsened, and everyone thought I would surely die.” After taking a prescription from his father, he miraculously recovered in less than two days. This experience made Li Shizhen realize the wonders of medicine![5] It significantly influenced his future path. After failing the examinations three times in 1540, Li Shizhen decided to stop taking the exams, stating, “If I cannot be a good minister, I will be a good doctor.” The deep family tradition provided him with a new life path. He returned home and “studied for ten years without leaving the courtyard,” leading a life of extensive reading and medical research.[6] From then on, his medical skills improved, and his reputation spread. More importantly, he had a heart for helping others, as reflected in the saying, “Traveling a thousand miles to deliver medicine without charge.”[7]

2

“At thirty, I strive to edit and compile”—— Personal responsibility for the national pharmacopoeia A physician must be well-versed in pharmacopoeias. Ancient Chinese pharmacopoeias, generally referred to as Ben Cao, began with the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (Shen Nong’s Classic of Materia Medica) and were enriched by successive generations of physicians. The Tang Dynasty’s official pharmacopoeia established the tradition of government-organized pharmacopoeia compilation. By the Ming Dynasty, there were over 41 pharmacopoeias in circulation, mostly old works from previous dynasties, with inconsistent formats and outdated content. During his practice, Li Shizhen felt that various pharmacopoeias were filled with errors and misled the public, “Some items were split into two or three, while others were confused as one.” Thus, he conceived a bold idea: to revise the pharmacopoeia. This was a daring endeavor because since the Tang Dynasty, the revision and publication of pharmacopoeias had primarily been undertaken by the government. Although there were some private writings during the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, they focused on specific aspects, and it was nearly impossible for an individual to systematically reorganize and revise a pharmacopoeia without significant manpower, financial resources, and material support. When Li Shizhen contemplated this grand project, many of his contemporaries in the Ming Dynasty were more prestigious, older, and held higher positions than him. Besides his solid medical foundation, his only direct advantage was his grand ideal and enduring patience. He was determined to undertake this project! Without government funding, the research team consisted of his family members.[8] The difficulty of independently shouldering such a national project is unimaginable. Instead of focusing on practicing medicine and educating the next generation for a more comfortable life, his ideals and patience drove him to pursue this path relentlessly… In the thirty-first year of the Jiajing era (1552), the local physician Li Shizhen from Qizhou embarked on the long journey of compiling the pharmacopoeia, “Fishing through numerous books and gathering knowledge from various sources”[9] and “Exhaustively searching and collecting, correcting errors and filling gaps”[10] This endeavor lasted nearly 30 years…

3

“I wish to ask for a word to ensure immortality”—— Ten years seeking a preface for publication In the sixth year of the Wanli era (1578), the Ben Cao Gang Mu was completed, consisting of 52 volumes divided into 16 sections and 60 categories, listing 1,892 medicinal substances, adding 374 new substances, with 11,096 prescriptions and 1,109 illustrations. However, the completion of the manuscript was just the beginning. The biggest problem facing Li Shizhen was: who would fund the publication of such a massive work? During the Ming Dynasty, the publishing industry was thriving, and printing technology was advanced, but the prosperity of the publishing industry had no direct relation to Li Shizhen. A work that did not conform to the relevant publishing policies, lacked funding, and was not a popular topic could only be self-funded or solicited; otherwise, it would be impossible to publish. How much money was needed to publish a book?

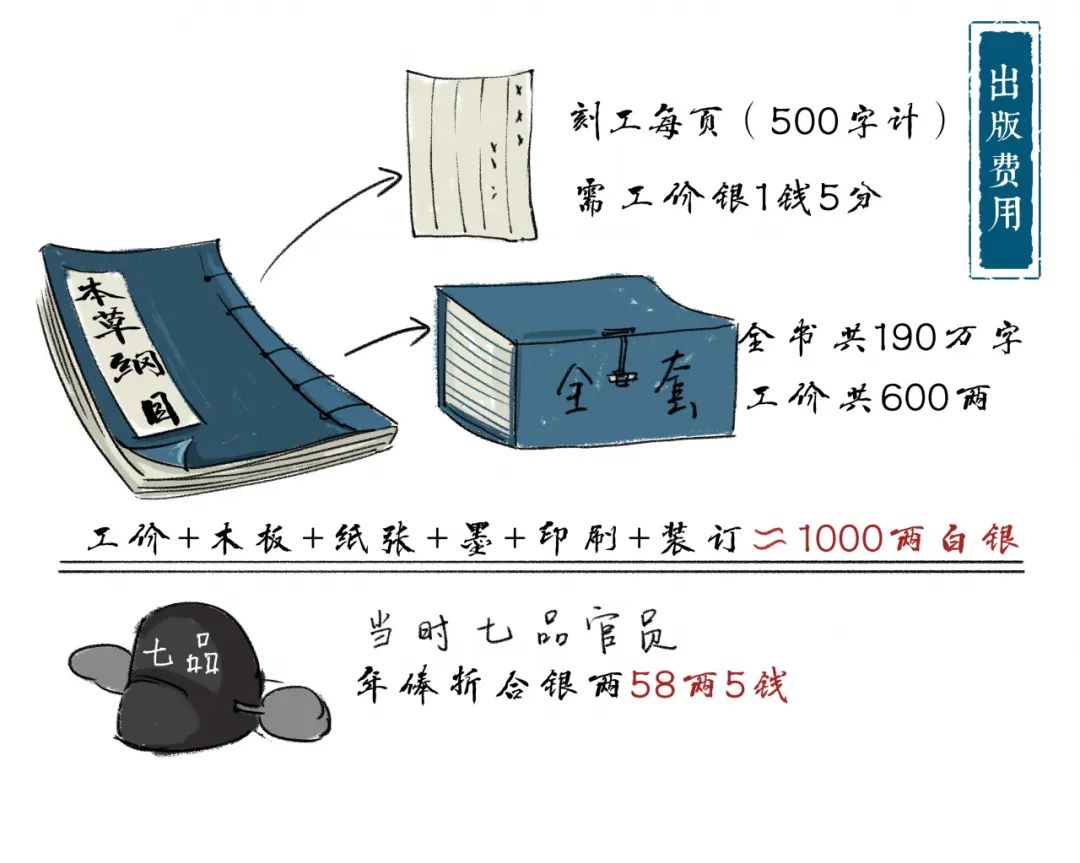

► Comparison of Ming Dynasty salaries and publishing costs

In the Ming Dynasty, the cost for engravers was 1.5 silver coins per page (based on 500 characters), and the Ben Cao Gang Mu totaled 1.9 million characters, meaning the engraving cost alone would be nearly 600 taels. Adding the costs of woodblocks, paper, ink, printing, and binding, the total would be around 1,000 taels of silver. At this time, how was Li Shizhen’s family situation? Among the Li family, his son Li Jianzhong was serving as the county magistrate of Pengxi in Sichuan, a seventh-rank official with the highest rank and income, earning an annual salary equivalent to 58 taels and 5 coins. Given Li Shizhen’s medical ethics of often treating patients without charge, the family’s annual income from medicine could only be less than this salary. Even if Li Jianzhong donated his entire salary, it would take over ten years to gather the 1,000 taels needed. Clearly, self-funding was not feasible. Unable to afford the publication costs, he had to seek help from patrons. Li Shizhen first sought funding in nearby Huangzhou and Wuchang, either appealing to officials for publication funds or asking booksellers for assistance, but to no avail. One can imagine the scene at that time; wherever he went, Li Shizhen’s efforts were met with affirmation and praise: “Such a work is truly rare,” “Your spirit is commendable,” “As for publication, the costs are simply too high, and our resources are limited; you should try elsewhere.” After nearly a year of such efforts, there were no results.

► In the Ming Dynasty, booksellers were also hesitant to publish scholarly works.

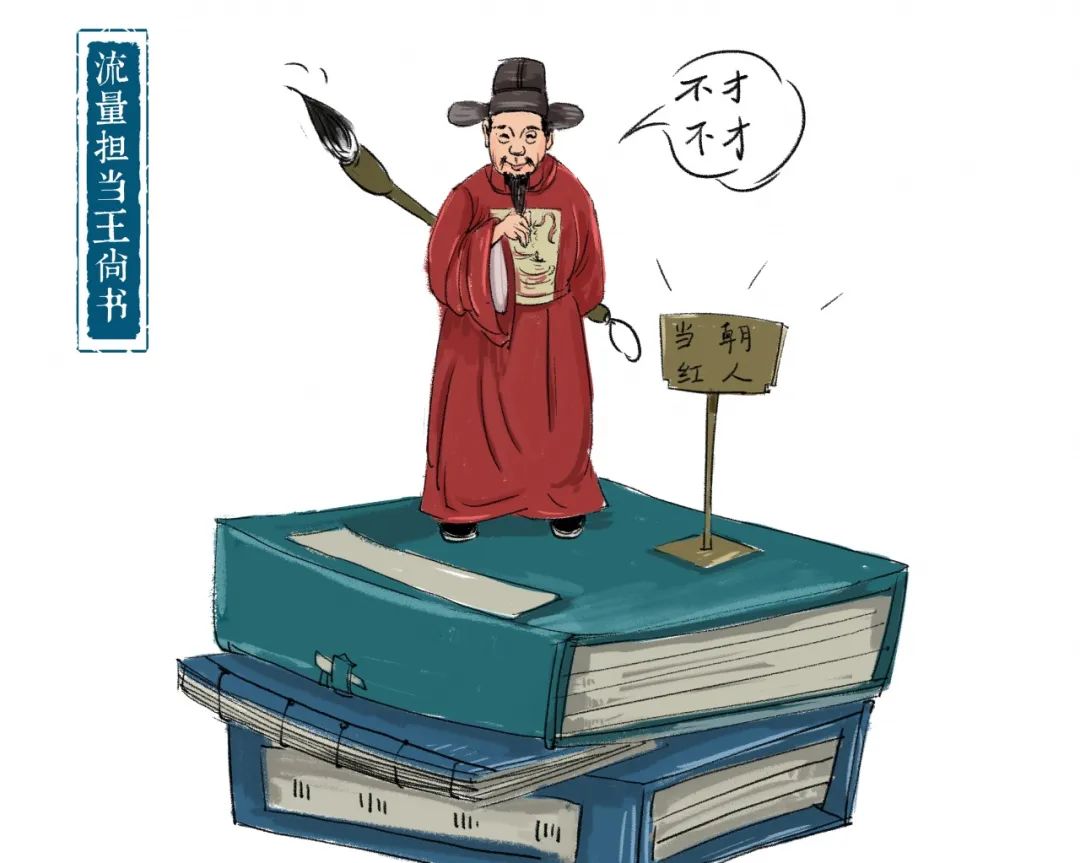

With no success in his hometown, he decided to go to Nanjing for a chance. As one of the capitals of the Ming Dynasty, it was a famous center for book publishing. In the seventh year of Wanli (1579), 63-year-old Li Shizhen went to Nanjing to seek publication opportunities for his work. “Jinling is the capital of books,” with numerous bookstores and great prosperity, yet after a year of searching, not a single bookseller was willing to publish the book. The consensus among booksellers was that they preferred exciting content with illustrations, such as dramas and novels, especially those with thrilling plots. Practical books, like examination simulation questions (preferably with endorsements from famous scholars), also had a large market. This old man from Hubei with his dictionary of medicinal substances had no market appeal, no fame, and even if printed, no one would buy it. During his market search, someone advised Li Shizhen that since government funding was unlikely, the only feasible way was to have a prominent figure write a preface to recommend the book, which might persuade booksellers to publish it. The most prominent figure at the time was Wang Shizhen, a leading literary figure known for his high talent and reputation. Many sought him to write prefaces, and it is said that he wrote as many as 319 prefaces for others. Of course, when seeking a preface from someone he did not know, a generous fee was likely expected, and once he agreed to write a preface, the book’s value would increase significantly.[12] In the eighth year of Wanli (1580), Li Shizhen traveled down the river to Wang Shizhen’s home in Taicang, saying, “I wish to ask for a word to ensure immortality.” At that time, Wang was deeply engrossed in Taoist practices, and when Li arrived, Wang was preparing a “transcendence ceremony” for his much younger female disciple, Wang Taozhen.[13] Given the circumstances, the vast differences in their worldviews made mutual understanding difficult. One revered Taoist practices, while the other despised them, creating a significant gap in their perspectives.

► Wang Shizhen was a significant figure in the literary world at the time.

After some polite exchanges, Wang did not indicate whether he would write a preface for Li, but instead wrote a poem for him, claiming it was a “playful gift.” The poem read: “Li, you resemble the tree by the river, and I see the immortal crossing the dragon. You bring forth the book from the blue bag, as if seeking a preface from the mysterious master. The true essence of Huayang wants to approach immortality, but annotating the pharmacopoeia delayed me for ten years. Why not let your son do it instead, as he can ascend to the heavens?” This poem, rich in allusions, is filled with mockery and advice, suggesting that at the time of his immortal teacher’s transcendence, Li Shizhen came to seek a preface. Just as Tao Hongjing was delayed for ten years by annotating the pharmacopoeia, Wang suggested that such matters should be left to Li’s son, and that focusing on Taoist practices was the real priority. This reflects the traditional Chinese custom of politely declining requests while maintaining courtesy. Although later generations often interpret this poem with idealistic goodwill, the reality was that Li Shizhen left empty-handed after seeking a preface from a famous figure. In fact, the difficulty in obtaining a preface from Wang Shizhen stemmed from his own struggles with such requests. In a preface he wrote for a friend the following year, he expressed his difficulty in praising others without sincerity and his desire to refrain from writing prefaces altogether.[14] Perhaps Wang Shizhen felt that although he could be compensated, he was not lacking in money, did not know Li well, and had no interest in reading his book, thus he felt entitled to refuse. Li Shizhen’s mood likely did not improve; with no success in obtaining a preface, publication was impossible. He returned home to continue revising the manuscript and wait… Ten years later, in the eighteenth year of Wanli (1590), Li was already 73 years old. As the saying goes, “At seventy-three, eighty-four, the King of Hell does not invite you, you go yourself.” At this point, Li Shizhen, suffering from old age and illness, felt that if he did not try again, he might not see his work published in his lifetime. Thus, he approached Wang Shizhen for a second time. Perhaps moved by the old man, Wang finally agreed to write a preface. In the preface, he described the scene of their meeting: a thin old man enthusiastically introducing the Ben Cao Gang Mu, resembling “a person south of the Big Dipper.” Wang then recorded a summary of Li Shizhen’s self-description. After “carefully reading” the manuscript, Wang Shizhen’s attitude was markedly different from ten years prior. He lamented that this book should not be viewed merely as a medical text, but as “the subtle essence of nature and principles, a classic of material investigation, a secret record for emperors, and a treasure for the people,” and praised Li Shizhen, saying, “Li, your dedication is truly commendable!” Wang Shizhen passed away in the same year the preface was completed.

4

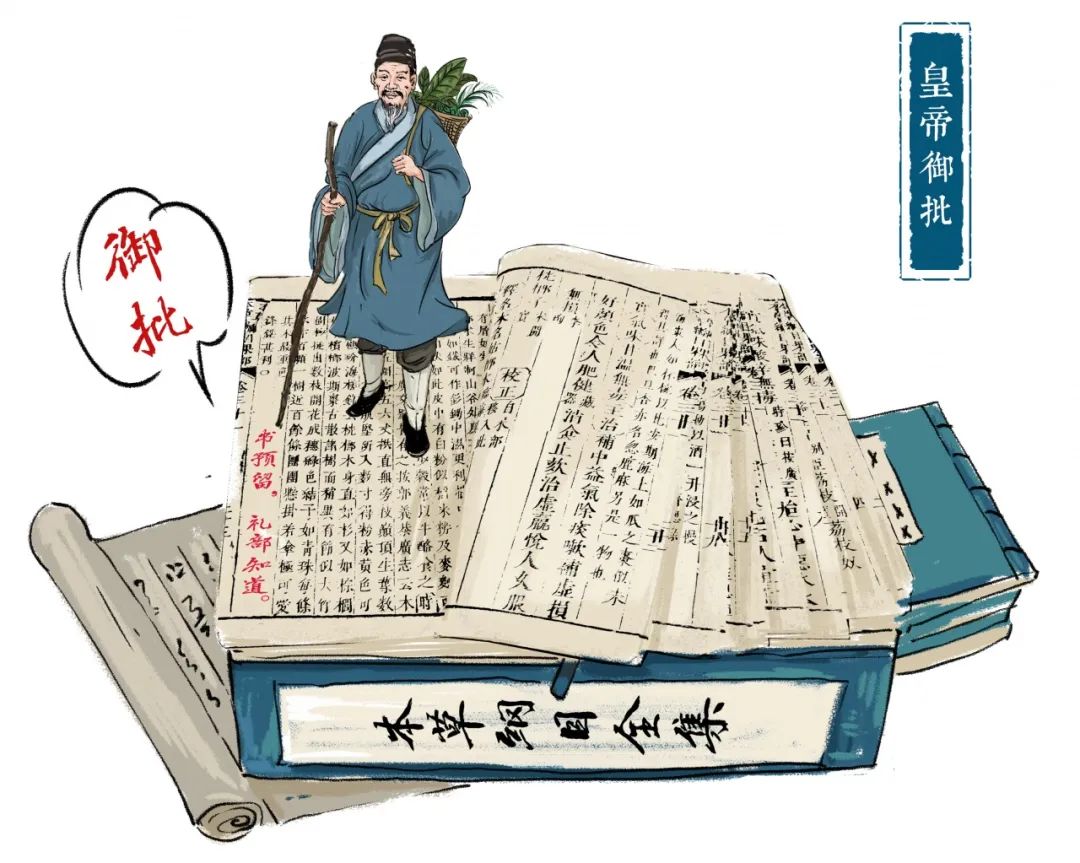

“The book remains for review, the Ministry of Rites is informed”—— Posthumously awarded the title of Taixue Hospital Judge With Wang Shizhen’s preface, the bookseller Hu Chenglong decided to take a risk, believing that sales should not be a problem, though he was uncertain about the volume. History played a joke on Hu; he likely never imagined that after a lifetime of publishing many books and earning considerable profits, the work that would immortalize him in history would be the Ben Cao Gang Mu, which had initially been overlooked. The engraving and printing process takes time, and as a businessman prioritizing profit, Hu Chenglong could not afford to let craftsmen invest too much time and effort into a work with uncertain profitability. How long did it typically take to engrave and print a book of similar content at that time? In the second year of Jiajing (1523), the Shandong government took a year to engrave and print the Zheng Lei Ben Cao. In the thirty-first year of Wanli (1603), the governor of Jiangxi, Xia Liangxin, took six months to reprint the Ben Cao Gang Mu (“It took six months to complete”); in the thirteenth year of Chongzhen (1640), the bookseller Qian Weiqi took eight months to reprint the Ben Cao Gang Mu (“It took eight months to complete”). Three years later, in the twenty-first year of Wanli (1593), the book was still in the engraving process. Li Shizhen, who was waiting for publication in Nanjing, passed away, never having seen his work published. Three years after his death, the Ben Cao Gang Mu was finally printed, taking six years from engraving to publication. The delay was not due to the author’s revisions but rather the bookseller’s issues. After nearly 30 years of effort, with three revisions of the manuscript, the aging and ailing author hoped to see the book published quickly and would not have troubled the publisher again. This illustrates the difficulties of publication. In six years, if funds were sufficient and conditions met, ten similar books could have been printed. What might Li Shizhen have thought before his death? Given his attitude towards writing, he likely thought that the engraving must be flawless, that he should present the book to the court to attract attention, and that once the book circulated, people would no longer suffer from the errors of previous generations. In November of the twenty-fourth year of Wanli (1596), Li Shizhen’s second son, Li Jianyuan, a Confucian student from Huangzhou, went to the capital to present the printed 58 copies of the Ben Cao Gang Mu and his father’s memorial to the court. This was because two years prior, in the twenty-second year of Wanli (1594), the court had ordered the collection of lost works while compiling the national history. Li Jianzhong stated in his memorial: “Just as the book was completed, my father suddenly passed away.” This was undoubtedly a comforting statement; otherwise, he would not have waited three years after the book was completed to present it. If Li Shizhen’s memorial was filled with hope for the court, Li Jianyuan’s memorial reflected a mix of emotions. Sixteen years after the manuscript was completed, it finally came to fruition. After numerous rejections and setbacks, it ultimately achieved success. “If the father has a will, the son must follow; if the father has a work, the son must present it. How can we fulfill the father’s aspirations?” In the eyes of Li Shizhen and his son, “To govern oneself is to govern the world; the book should shine as brightly as the sun and moon, ensuring the longevity of the nation and the people.”[15] This submission aimed to gain national recognition and seek an explanation. On November 18, the long-ignored Wanli Emperor commented on Li Jianyuan’s memorial: “The book remains for review, the Ministry of Rites is informed, thus decreed.”[16]

► The emperor’s decree “The book remains for review, the Ministry of Rites is informed” made this book a classic. One result of the emperor informing the Ministry of Rites was the posthumous award of the title of Taixue Hospital Judge (a sixth-rank honorary title), equivalent to a current departmental-level official. During his lifetime, Li Shizhen had already received two titles: one for his exceptional medical skills, recommended for a position in the Chu Wangfu (Chu Prince’s Mansion), and the other due to his eldest son Li Jianzhong’s official position, receiving the honorary title of Wenlin Lang, County Magistrate of Pengxi (a seventh-rank honorary title). Young Li Shizhen did not achieve fame through the imperial examinations but gained recognition from the court through his work. In his later years, he struggled for over a decade for the publication of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, and when he passed away, he had not seen it printed. Yet, this work became sought after and renowned, leaving a mark in history. These are likely things he never dared to imagine.

5

“An Encyclopedia of Ancient China”—— The Eastern Medical Classic Captivates the World The Ben Cao Gang Mu, engraved and printed in Nanjing by Hu Chenglong, is considered the original version of the book, also known as the Jinling First Edition. Due to engraving quality and funding issues, the printing was not very meticulous, and the print run was limited. However, regardless of the quality, this version reflects the original appearance of Li Shizhen’s work. To date, only eight copies of the Jinling edition are known to exist (seven in public collections and one in private collection). After the Jinling edition was published, the Ben Cao Gang Mu was reprinted four times during the Ming Dynasty, and by the time of the Chongzhen era, this initially overlooked book had become widely circulated and highly regarded. After entering the Qing Dynasty, the book was repeatedly reprinted by various families and institutions, and by 1912, there were 61 different versions of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. Currently, there are over 100 Chinese versions of the book available. Li Shizhen has been honored with titles such as “Saint of Medicine” and “Great Natural Scientist” from various circles. Moreover, the Ben Cao Gang Mu is highly esteemed internationally. It reached Europe in the 18th century and was first translated into French in the 1735 edition of the General History of the Chinese Empire. Subsequently, English, German, Russian, and Latin versions appeared, sparking great interest among European scholars. The British biologist Charles Darwin cited the Ben Cao Gang Mu over a dozen times in his 1859 work, On the Origin of Species, referring to it as “an encyclopedia of ancient China.” In the late 19th century, the Russian physician Belev praised the Ben Cao Gang Mu as a classic of Chinese materia medica, stating, “Li is undoubtedly an outstanding writer in the field of natural science in China throughout history.” The renowned British scholar Joseph Needham regarded the Ben Cao Gang Mu as the greatest scientific achievement of the Ming Dynasty, placing its author, Li Shizhen, alongside Galileo and Vesalius as a giant of the Western Renaissance. If Li Shizhen were aware of this, he would surely feel immense satisfaction!

[1] Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume 38, Section on Clothing and Equipment, Patient’s Clothing.

[2] Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume 5, Water Section, “Thus, the nature and flavor of water are especially important for those concerned with health… Water near urban ditches is mixed with pollutants and becomes alkaline; it must be boiled and allowed to settle for a while before use, otherwise, it will taste foul.”

[3] Li Shizhen’s brothers erected a tombstone for their father, Li Yanwen, stating: “The late Li Gong, who served in the Imperial Medical Institute.”

[4] From Wang Shizhen’s preface to the Ben Cao Gang Mu: “I am from Jingchu, often ill in my youth, and devoted to reading, as if I were eating sugarcane.”

[5] Li Shizhen’s self-description in the Ben Cao Gang Mu: “At the age of twenty, I fell ill due to a prolonged cold and cough, leading to a fever that made my skin feel like it was on fire. After a month, it worsened, and everyone thought I would surely die. My father thought of Li Dongyuan’s treatment for lung heat, and prescribed a decoction of Huang Qin (Scutellaria) which cured me in two days. The wonders of medicine are indeed profound!”

[6] From Gu Jingxing’s Bai Mao Tang Ji: “He studied for ten years without leaving his courtyard, and was well-versed in all subjects. A good doctor is one who considers himself a doctor.”

[7] From the Qizhou Zhi, Volume 11, Biography of Li Shizhen.

[8] According to the original Jinling edition of the Ben Cao Gang Mu: Edited by Li Shizhen, with corrections by his sons Li Jianzhong and Li Jianyuan, and revisions by his grandsons Li Shuzong, Li Shusheng, and Li Shuxun, with illustrations by Li Jianzhong and Li Jianyuan.

[9] From Wang Shizhen’s preface to the Ben Cao Gang Mu.

[10] From the Ming History, Volume 299, Biography of Li Shizhen.

[11] From Ye Dehui’s Shulin Qinghua, Volume 7.

[12] From the Ming History, Volume 287, Biography of Wang Shizhen, “A few words of praise can greatly increase the value of a work.”

[13] At that time, Wang Shizhen was 55 years old, and Wang Taozhen was 23 years old, a disciple of Wang Xijue, who had a passion for Taoism and passed away when Li Shizhen visited Wang Shizhen.

[14] From Wang Shizhen’s preface to the Green Loquat Pavilion Poetry Collection: “I cannot flatter others, nor can I make everyone satisfied, so I wish to refrain from writing altogether.”

[15] From Li Jianyuan’s memorial regarding the Ben Cao Gang Mu.

[16] From the Ming Shilu, Volume 271.

END

This article is exclusively reported by the “Cultural Tourism China” client.

Comic Creation: Huang Zhuo

Editor: Li Zheng

Source: China Cultural Report