Poria (Fu Ling)

The term “authentic medicinal materials” first appeared in the late Ming Dynasty in the play “Peony Pavilion” by Tang Xianzu[1]. Here, “Dao” refers to an administrative division in ancient China, equivalent to a modern province, while “Di” refers to the specific production area below the “Dao” level. As early as the Eastern Han Dynasty, the “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing” recorded that “the land produces, authenticity varies, and each has its method,” emphasizing the importance of distinguishing medicinal materials by their origin[2]. The “Ben Cao Jing Ji Zhu” further noted that “many come from near the Dao, with their qi and properties not as good as those from the local area. Therefore, the efficacy of medicines from other regions may not be as effective as those from the local area. Although there are exchanges of Shu and Bei medicines, they are not of the finest quality”[3]. This text describes the authenticity of over forty commonly used medicines using terms like “first,” “best,” “good,” and “superior,” further discussing the importance of “authentic” medicinal materials. Xie Zongwan[4] believes that authentic medicinal materials refer to those produced in specific natural conditions and ecological environments, with concentrated production, careful cultivation techniques, and processing, resulting in higher quality and efficacy compared to those produced in other regions. Thus, the name of the medicinal material is often prefixed with its place of origin to indicate its authenticity. It is evident that authentic medicinal materials are always linked to their environment. The authentic medicinal materials that have been passed down through generations have now developed new scientific connotations, and the cultivation of authentic medicinal materials is gradually being standardized, promoting harmonious development of resources, ecology, culture, and economy[5]. This article takes Poria as an example to explore its discovery, changes in authentic production areas, biological characteristics, and modern applications, aiming to provide materials for the popularization of Poria.

1. Discovery of Poria

Poria was first recorded in the “Fifty-Two Disease Formulas” as “Fu Ling” and classified as a superior herb in the “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing”. In terms of medicinal efficacy, Poria is known for its ability to promote urination, drain dampness, strengthen the spleen, and calm the mind. Tracing the historical records of Poria’s origin, the ancient understanding of Poria has generally gone through four stages: ① Poria is formed from pine roots; ② Poria is formed from pine resin; ③ Poria is formed from the spiritual essence of pine; ④ Poria is a type of sclerotium. The recognition of “pine roots” and “pine resin” reflects people’s observational and inductive abilities, as they concluded from long-term practice that Poria often appears around the roots of pine trees, thus inferring a special relationship between Poria and pine trees. The third stage, the hypothesis of “spiritual essence of pine,” indicates that people had realized that Poria is a substance distinct from pine wood. With the continuous improvement of modern disciplines such as plant taxonomy and traditional Chinese medicine identification, it was ultimately discovered that Poria is the dried sclerotium of the fungus Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. The evolution of understanding regarding the origin of Poria among ancient and modern TCM practitioners reflects the traditional Chinese medicine’s foundation on practical experience. Ancient medical practitioners summarized theories from practice and then used these theories to guide further practice, forming a progressive cycle of “practice-theory-repractice” through repeated trial and error and correction, showcasing the dialectical and open-minded thinking of traditional Chinese medicine.

2. Changes in the Authentic Production Areas of Poria

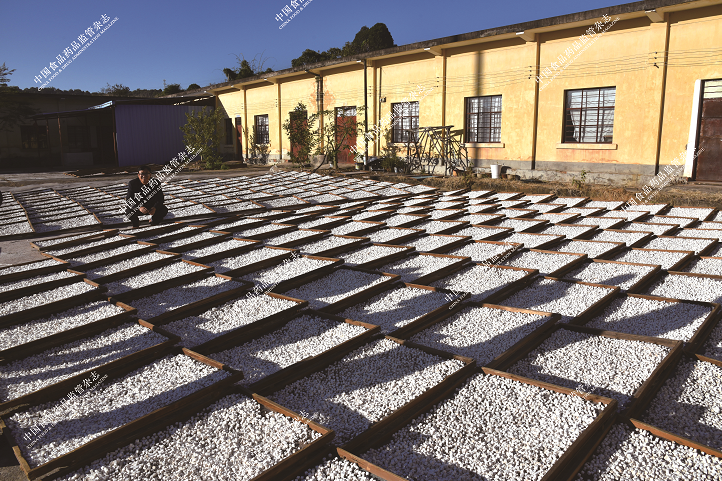

The cultivation of Poria is closely linked to pine resources. Historically, the main production areas of Poria have undergone several changes, mostly related to pine resources. According to historical records of Poria’s production areas in various Chinese herbal texts, before the Ming Dynasty, the main production areas were concentrated in Shandong, Henan, and Shaanxi, with early production also noted in places like Jiande in Zhejiang, Yulin in Guangxi, and Yibin in Sichuan. From the late Song to the early Ming Dynasty, northern China experienced years of war, leading to economic stagnation and destruction of forest resources, severely impacting medicinal material production. Consequently, the main cultivation area of Poria shifted south to the Dabie Mountains at the junction of Hubei, Henan, and Anhui, gradually achieving large-scale cultivation of Poria. After the Qing Dynasty, the Dabie Mountain area remained a major production area, with cultivation spreading to provinces such as Yunnan, Fujian, Guizhou, and Zhejiang, and a trading market for Poria established in Hunan, with wild Poria distributed across southern provinces[6]. In recent years, the promotion of Poria cultivation has been widespread across the country, with the results of the third national survey of Chinese medicinal resources indicating that the largest cultivation area and wild distribution of Poria is found in the border area of Yunnan and Sichuan, with large-scale cultivation also present in southern Shaanxi, southern Henan, Hubei, Anhui, and provinces south of the Yangtze River.

Poria cultivation base in the Dabie Mountains, Anhui. Photography: Que Ling

3. Biological Characteristics of Poria

The medicinal Poria comes from the sclerotium of the large fungus Poria, which is formed when fungal hyphae tightly intertwine under adverse environmental conditions or during the reproductive period, creating various types of mycelial tissues, resulting in a hard, kernel-like structure. The “Yao Wu Chu Chan Bian” states: “Those produced in Yunnan are called Yun Ling, which are the most authentic.”[7] This indicates that during the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China, Yunnan Poria was highly regarded as an authentic medicinal material primarily due to the particularly solid sclerotia of wild Poria from Yunnan. As wild resources have diminished, artificial cultivation has become the primary method relying on sclerotia.

Commercial cultivation of Poria typically employs asexual reproduction, using methods such as meat spawn, wood spawn, paste spawn, and mycelium spawn. Meat spawn involves using the sclerotium directly as the spawn; wood spawn involves attaching the sclerotium to logs, which are then cut into small sections after the mycelium has fully grown; paste spawn involves crushing the sclerotium into a paste for spawning; and mycelium spawn is a cost-effective method that is widely adopted for large-scale cultivation. Poria has a parasitic relationship with pine trees, requiring a large amount of pine resources for cultivation. According to current estimates of the national Poria market, the annual demand for fresh Poria is about 100,000 tons, consuming approximately 560,000 cubic meters of Masson pine wood. On average, each acre of Masson pine forest has about 2.7 cubic meters of wood storage. Based on a 10-year growth and rotation cycle, approximately 2.2 million acres of pine trees are needed specifically for Poria production. The above-ground parts of pine trees can be commercially utilized, while the underground parts can support Poria reproduction, maximizing resource utilization.

Poria cultivation bag material. Photography: Que Ling

Poria cultivation bag material. Photography: Que Ling

4. Future Applications of Poria

As people’s living standards continue to improve, there is an increasing focus on health and wellness, making the layout of the health-related industry a hot topic. As of 2018, Poria is the only fungal medicine listed in the “Directory of Substances that are Both Food and Medicinal Materials According to Tradition” (draft for public comment), thus Poria can be consumed as a food-medicinal substance. Currently, the Poria products circulating in the market include raw Poria spawn, fresh Poria; semi-processed products such as Poria slices, cubes, rolls, powder, Poria skin, Fu Shen, and Poria extracts; and deep-processed products like Poria facial masks, Poria tea, Poria wine, and Poria porridge. In the future, Poria’s applications in food, beverages, alcoholic products, and cosmetics are promising, and it can also be used in conjunction with other herbs and extracts.

Left image: Poria cubes, slices, blocks, and rolls

Middle image: Poria and pine roots

Right image: Fu Shen

Hand-drawn: Xun Yiqiao

Introduction to Members of the Fungal Medicinal Family

Fungi are a major group of eukaryotic organisms, including microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the well-known mushrooms. Fungi constitute their own kingdom, distinct from plants, animals, and other eukaryotes. Medicinal fungi are mainly distributed in the Basidiomycetes and Ascomycetes classes, and below is a summary of typical medicinal materials under each class.

① Sclerotium type

Polyporus: The dried sclerotium of the fungus Polyporus, mainly distributed in provinces such as Shaanxi, Hebei, and Yunnan.

Leigong: The dried sclerotium of the fungus Leigong, mainly distributed in northwestern, southwestern, and southern China.

② Fruiting body type

Ganoderma: The dried fruiting body of the fungus Ganoderma or Lingzhi, which refers to the structure formed during reproduction that has specific characteristics and can produce spores. Mainly distributed in Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, Guangdong, and Guangxi.

Author Biography

Que Ling, Master, Research Assistant, Institution: Beijing Normal University (Zhuhai Campus) Institute of Innovation and Development Research. Specialization: Protection of Chinese medicinal resources.

Are you “watching” me?