1. Pulse Diagnosis*

Pulse diagnosis is a method where the physician uses the fingertips to palpate specific arteries (such as the Renying Mai (Renying pulse), Cunkou Mai (Cunkou pulse), and Fuyang Mai (Fuyang pulse)) on the patient to observe changes in the pulse characteristics, known as Mai Xiang (pulse patterns). This method has a long history in China, receiving significant attention from physicians throughout the ages, and has accumulated rich theoretical and practical experience, making it a distinctive feature of TCM diagnostics.

The blood vessels circulate throughout the body, nourishing the internal organs and moistening the muscles, bones, and various organ openings. Additionally, the blood in the vessels is directly linked to the five organs, such as the heart governing blood, the heart generating blood, the spleen controlling blood, and the liver storing blood. Therefore, the normalcy of blood circulation directly reflects the physiological and pathological states of the internal organs and the body as a whole. In other words, the pulse patterns reflect the health and disease of the body. Some diseases may alter the pulse patterns even before clinical symptoms appear. Clinical practice has confirmed that various pathological changes, such as exterior, interior, deficiency, excess, cold, and heat, can manifest as corresponding changes in the pulse patterns. Thus, pulse diagnosis is one of the reliable diagnostic methods with both theoretical and practical foundations.

(1) Locations for Pulse Diagnosis

The locations for pulse diagnosis vary depending on the chosen method. There are generally three methods: comprehensive pulse diagnosis, three-position pulse diagnosis, and Cunkou pulse diagnosis. Comprehensive pulse diagnosis examines the pulse at three specific arteries simultaneously: the head, hands, and feet; three-position pulse diagnosis examines the Renying, Cunkou, and Fuyang arteries simultaneously; while Cunkou pulse diagnosis focuses solely on the Cunkou artery. The comprehensive and three-position methods are rarely used today, with the Cunkou method being the most widely applied.

The Cunkou, also known as the Qikou (Qi mouth) or Mai Kou (pulse mouth), is located on the radial side of the wrist. The pulse can be felt where it beats. The Cunkou pulse can reflect systemic changes because it is the convergence point of the body’s blood vessels, belonging to the Shou Taiyin Fei Jing (Hand Taiyin Lung Meridian), where the blood vessels converge in the lungs (“the lungs govern the hundred vessels”). The Hand Taiyin Lung Meridian starts in the middle jiao, where the spleen and stomach reside, which are the source of the body’s Qi and blood. Therefore, examining the Cunkou pulse can reveal the conditions of the five organs and six bowels, as well as Qi and blood changes.

The Cunkou pulse is divided into three sections: the Guan (barrier) at the wrist bone, the Cun (inch) before the barrier, and the Chi (尺) after the barrier, with a total of six sections across both hands. (See Figure 47)

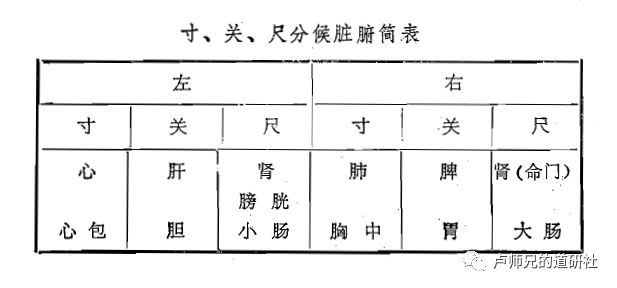

Regarding the allocation of the three sections to the internal organs, there have been many differing opinions among physicians throughout history, but the basic spirit remains consistent. The commonly accepted allocation method today is: the left hand’s Cun, Guan, and Chi correspond to the heart (pericardium), liver (gallbladder), and kidney (bladder, small intestine); the right hand’s Cun, Guan, and Chi correspond to the lung (chest), spleen (stomach), and kidney (mingmen, large intestine). This allocation reflects the principle of “upper (Cun) corresponds to the upper (upper jiao), middle (Guan) corresponds to the middle (middle jiao), and lower (Chi) corresponds to the lower (lower jiao).”

(2) Methods of Pulse Diagnosis

During pulse diagnosis, the patient should sit or lie down with their arm at the same level as the heart, palm facing up, and the arm resting naturally. For adult patients, the three-finger positioning method is used, where the physician first places the middle finger on the wrist bone to locate the Guan section, then the index finger on the section before the Guan to locate the Cun section, and the ring finger on the section after the Guan to locate the Chi section. The three fingers should be positioned in a natural arc and pressed at the same level, with the fingertips touching the pulse. The spacing between the fingers should be adjusted according to the patient’s height, generally with a slight gap between them. For children, if the Cunkou pulse is too short to accommodate three fingers, the “one finger to locate three sections” method can be used, without subdividing into three sections. For children under three years old, the fingerprint observation method can replace pulse diagnosis.

The pressure applied during pulse diagnosis is categorized based on the physician’s finger strength into three types: superficial, moderate, and deep, also known as lifting, searching, and pressing. Light pressure on the pulse is termed superficial, also known as “lifting”; moderate pressure that reaches the muscle is termed moderate, also known as “searching”; and heavy pressure that reaches the tendons and bones is termed deep, also known as “pressing”. Each of the three sections (Cun, Guan, Chi) has three types of pressure (superficial, moderate, deep), resulting in a total of nine assessments, hence also referred to as “three sections and nine assessments”.

During pulse diagnosis, both the physician and patient should pay attention to certain issues. The environment should be quiet, and the patient should rest for a moment before the diagnosis. Historically, it has been advocated to perform pulse diagnosis in the morning before eating, but this is often difficult to achieve today. Any time can be used, but it is still preferable to do so in the morning or at a time far removed from meals. The physician must focus and carefully observe the pulse patterns. Additionally, the physician’s breathing should be even to accurately assess the patient’s pulse rate. The duration of pulse diagnosis should not be less than three minutes; if the pulse patterns are difficult to discern, the time should be extended.

(3) Normal Pulse Patterns

Normal pulse patterns, also known as Ping Mai (regular pulse) or Chang Mai (common pulse), have a pulse rate of four beats per breath (one inhalation and exhalation). The pulse is characterized by a gentle, strong, and even rhythm, with all three sections (Cun, Guan, Chi) and the three types of pressure (superficial, moderate, deep) showing a pulse. The three main characteristics of a normal pulse are: having Wei (stomach), Shen (spirit), and Gen (root), which refer to the pulse’s regularity, strength, and depth. In clinical practice, the presence or absence of “Wei, Shen, Gen” is a primary basis for judging the strength or weakness of the vital Qi and predicting prognosis.

The pulse patterns are closely related to the internal and external environments of the body, not only reflecting changes in disease states but also showing physiological variations due to age, gender, constitution, and mental state. Younger individuals tend to have faster pulse rates. Young adults with strong physiques have strong pulses, while older individuals with weaker physiques have weaker pulses. Adult females generally have slightly weaker and faster pulses than adult males. Taller individuals have longer pulse presentation areas, while shorter individuals have shorter areas. Lean individuals often have slightly superficial pulses, while overweight individuals tend to have deeper pulses. Additionally, heavy physical labor, intense exercise, long walks, alcohol consumption, overeating, and emotional agitation can lead to faster and stronger pulses, while hunger can result in weaker pulses. The pulse patterns of normal individuals can also vary with seasonal changes. For example, in spring, the pulse may be slightly wiry, in summer, slightly surging, in autumn, slightly superficial, and in winter, slightly deep. These variations are all considered “normal pulses” and should be distinguished from pathological pulses.

Some individuals may not have a pulse detectable at the Cunkou section but may feel it slanting from the Chi section towards the back of the hand, known as Xie Fei Mai (slanting pulse), while others may feel the pulse on the back of the hand, known as Fan Guan Mai (reversed pulse), both of which are due to anatomical variations in the radial artery and are not considered pathological pulses.

(4) Pathological Pulses and Their Main Diseases

In pathological states, changes in the internal organs, meridians, Qi, and blood lead to corresponding changes in pulse patterns, referred to as pathological pulses. Through pulse diagnosis, one can understand the location and nature of the disease, providing a basis for syndrome differentiation and treatment. Therefore, pulse diagnosis holds significant clinical importance.

Regarding the types of pulse patterns, there have been various interpretations throughout history. In modern times, they are often classified into twenty-eight types. The following are introduced:

1. Floating Pulse

Pulse Pattern: Easily felt with light pressure, weak with heavy pressure. Characterized by a superficial pulse presentation.

Main Disease: Generally indicates exterior syndrome. It reflects the presence of external pathogens attacking the exterior, with the vital Qi moving towards the exterior to resist the pathogen. A strong floating pulse indicates an exterior excess, while a weak floating pulse indicates an exterior deficiency. If a long-term illness leads to a floating pulse that is large and weak, it indicates a critical condition of Yang Qi deficiency.

2. Deep Pulse (Fu Fu Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Not felt with light pressure, only detectable with heavy pressure. Characterized by a deep pulse presentation.

Main Disease: Indicates interior syndrome. When pathogens are trapped inside, Qi and blood are obstructed, resulting in a strong deep pulse indicating interior excess. If Yang Qi is deficient and unable to propel blood, the pulse will be deep and weak, indicating interior deficiency.

3. Slow Pulse (Chi Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Pulse beats slowly, with less than four beats per breath (less than sixty beats per minute).

Main Disease: Indicates cold syndrome. It reflects cold congealing the blood vessels, obstructing Yang Qi and making it difficult for blood to circulate. A strong slow pulse indicates cold accumulation, while a weak slow pulse indicates Yang deficiency with internal cold.

4. Rapid Pulse (Shu Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Pulse beats quickly, with more than five beats per breath (more than ninety beats per minute).

Main Disease: Indicates heat syndrome. It reflects heat pathogens stimulating Qi and blood, accelerating circulation. A strong rapid pulse indicates excess heat, while a weak rapid pulse indicates deficiency heat.

5. Deficient Pulse

Pulse Pattern: Weak in all three sections, feels empty upon pressure. A general term for weak pulses.

Main Disease: Indicates deficiency syndrome, often due to both Qi and blood deficiency. Insufficient Qi and blood lead to weak pulses.

6. Excess Pulse

Pulse Pattern: Strong in all three sections. A general term for strong pulses.

Main Disease: Indicates excess syndrome. When pathogens are strong and the vital Qi is not deficient, the pulse will be strong.

7. Slippery Pulse (Hua Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Smooth and flowing, with a round and slippery feel.

Main Disease: Indicates phlegm, food stagnation, and excess heat. It reflects internal obstruction of pathogens, with Qi and blood surging. During pregnancy, a slippery pulse may also be observed due to abundant and harmonious Qi and blood.

8. Choppy Pulse (Se Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Rough and uneven, like a light knife scraping bamboo.

Main Disease: A weak pulse indicates deficiency of essence and blood; a strong pulse indicates Qi stagnation and blood stasis.

9. Surging Pulse (Hong Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Pulses like surging waves, strong on the way in and weak on the way out. Characterized by a wide, strong pulse with significant fluctuations.

Main Disease: Indicates excess heat. It reflects internal heat filling the body, stimulating Qi and blood. A surging pulse may also be felt in cases of external heat illness affecting Yin, leading to a floating pulse that feels empty and weak upon pressure.

10. Thin Pulse (Xi Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Thin as a thread, soft and weak, but distinct upon palpation. Characterized by a narrow pulse with small fluctuations.

Main Disease: Indicates various deficiency syndromes, primarily Yin and blood deficiency. Insufficient Yin and blood lead to a thin pulse.

11. Weak Pulse (Ruo Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Weak and thin, with a soft pulse.

Main Disease: Indicates deficiency of both Qi and blood. Weak Qi leads to insufficient propulsion, resulting in a weak pulse.

12. Minute Pulse (Wei Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Extremely thin and weak, almost imperceptible.

Main Disease: Often indicates severe deficiency of Yang Qi.

13. Soft Pulse (Ru Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Floating and thin, easily felt but not distinct upon pressure.

Main Disease: Indicates deficiency and dampness. A soft pulse is due to insufficient Qi and blood.

14. String-like Pulse (Xian Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Straight and long, like pressing a guitar string.

Main Disease: Indicates liver and gallbladder diseases, pain, and phlegm. Qi stagnation in the liver and gallbladder leads to a tense pulse.

15. Tight Pulse (Jin Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Tense and tight, like a taut rope.

Main Disease: Indicates cold, pain, and food stagnation.

16. Scattered Pulse (San Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Floating and large, hollow like pressing a scallion tube.

Main Disease: Indicates blood loss, excessive sweating, or sudden damage to Yin fluids.

17. Rapid and Stopping Pulse (Cu Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Rapid and frequent, with intermittent stops.

Main Disease: Indicates excess Yang heat, blood stasis, Qi stagnation, phlegm, or food stagnation.

18. Knotted Pulse (Jie Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Slow with intermittent stops.

Main Disease: Indicates excess Yin, phlegm, or blood stasis.

19. Intermittent Pulse (Dai Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Weak and intermittent, with long pauses.

Main Disease: Indicates weak organ Qi, as well as wind, pain, fear, or trauma.

20. Long Pulse (Chang Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Extends beyond the normal range, like following a long pole.

Main Disease: Indicates heat syndrome.

21. Short Pulse (Duan Mai)

Pulse Pattern: Short and weak, not reaching the normal range.

Main Disease: Indicates Qi deficiency or Qi stagnation.

The above pulse patterns total thirty types, as the large pulse is often referred to as “Hong Da” (surging large), while the small pulse is the thin pulse, thus excluding these two, there are a total of twenty-eight pulses.

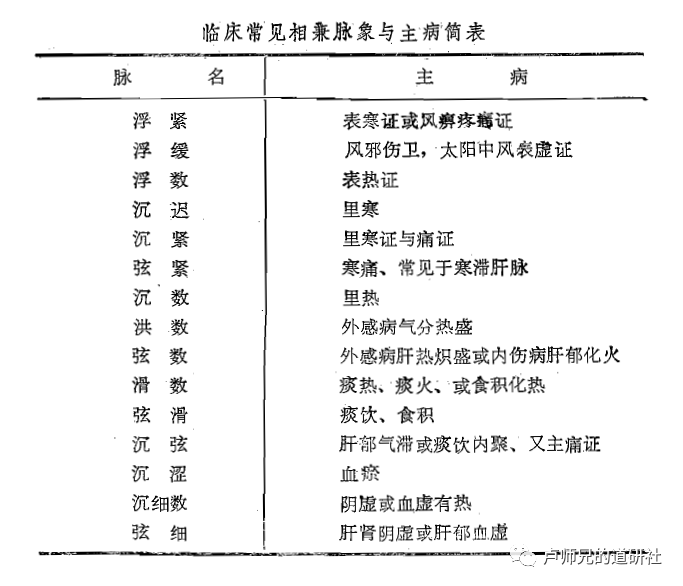

(5) Composite Pulses and Their Main Diseases

The causes of diseases are multifaceted, and the manifestations and changes of diseases are complex. Therefore, the pulse patterns commonly seen in clinical practice are often a combination of two or more single pulse patterns, known as Xiang Jian Mai (composite pulse). For example, soft pulses, rapid pulses, etc., are all considered composite pulses.

As long as they are not completely opposite single pulses (such as floating and deep pulses, slow and rapid pulses, etc.), they can coexist to form composite pulses, such as floating and tight, deep and slow, deep and thin rapid pulses.

The main diseases associated with composite pulses generally correspond to the sum of the main diseases of the individual pulses that make up the composite pulse. For example, a deep and slow pulse indicates interior cold syndrome, while a slow pulse indicates cold syndrome, thus the deep and slow pulse indicates interior cold syndrome. The rest can be inferred similarly. Below is a list of commonly seen composite pulses and their main diseases:

(6) The Relationship Between Pulse and Syndrome

The relationship between pulse and syndrome is very close. The so-called correspondence and non-correspondence between pulse and syndrome refers to whether they align or not. When they align, it is considered correspondence; when they do not, it is considered non-correspondence. This can serve as a reference for distinguishing the nature of the disease. Generally, when the disease is excess, the pulse is surging, rapid, or strong, indicating a correspondence between pulse and syndrome, suggesting that the pathogen is strong and the vital Qi is robust. Conversely, if the pulse is deep, thin, or weak, it indicates a non-correspondence, suggesting that the pathogen is strong and the vital Qi is weak, making it easy for the pathogen to invade. If a long-term illness presents with a deep, thin, weak pulse, it indicates that the vital Qi is recovering and the pathogen is retreating, suggesting improvement in the disease. However, if a new illness presents with a deep, thin, weak pulse, it indicates that the vital Qi has already weakened. In long-term illnesses, if the pulse is floating, surging, rapid, or strong, it indicates that the vital Qi is weak and the pathogen is advancing, which is a non-correspondence.

Since there are correspondences and non-correspondences between pulse and syndrome, there must be a true and a false aspect. Therefore, in clinical practice, careful differentiation is necessary to determine which to prioritize. One may prioritize the pulse over the syndrome or vice versa. For example, if there is abdominal distension and the pulse is weak, it indicates spleen and stomach Qi deficiency with Qi stagnation, where the distension is a false excess, while the weak pulse is a true deficiency, thus one should prioritize the pulse. In another example, in warm diseases where the fluids are severely damaged, the pulse may be floating and surging, indicating that the Yang Qi is floating, and although the pulse is surging, it feels empty and weak upon pressure, indicating that the syndrome is true deficiency while the pulse is false excess, thus one should prioritize the syndrome.

The pulse reflects only one aspect of the clinical manifestations of the disease, and therefore pulse diagnosis should not be the sole diagnostic basis. A comprehensive assessment using all four diagnostic methods is necessary to make an accurate diagnosis.

2. Palpation Diagnosis*

(1) Palpation of the Skin

Initially, if the skin feels hot and the heat diminishes with prolonged pressure, it indicates heat on the surface; if the heat intensifies with prolonged pressure, it indicates heat within; if the palms feel hot or the skin is hot without a sensation of evaporation, it indicates deficiency heat. If the skin or hands and feet feel cool, it indicates Yang deficiency and cold syndrome.

If the skin is moist, it indicates sweating; if dry, it indicates no sweating. If the skin is smooth and moist, it generally indicates that the body fluids are intact; if dry or rough, it indicates that the body fluids are damaged or there is blood stasis. If heavy pressure on the skin does not cause it to rise immediately, creating a pit, it indicates edema; if it rises upon lifting, it indicates Qi edema.

In surgical aspects, palpating the skin can help distinguish between Yin and Yang syndromes and whether pus has formed. For example, if a sore feels hard and not hot, with a flat and swollen base, it generally indicates a Yin syndrome. If it feels high and hot with a tight base, it generally indicates a Yang syndrome. If it feels fixed, hard, and hot or only slightly hot, it indicates that pus has not formed. If it feels hard on the edges and soft on top with a fluctuating sensation, it indicates that pus has formed.

There is also the “Chi Fu” method, which has certain significance in diagnosing warm diseases. Chi Fu refers to the skin from the inner elbow to the transverse wrist line. If the Chi Fu feels very hot, it is often seen in cases of exterior warm pathogen.

(2) Palpation of the Hands and Feet

If both hands and feet are cold, it generally indicates Yang deficiency and cold syndrome, or excess Yang counteracting Yin; if both are hot, it generally indicates excess heat or excess Yin counteracting Yang. If the palms are very hot, it often indicates internal injury with Yin deficiency and excess fire; if the backs of the hands are very hot, it often indicates an external disease.

(3) Palpation of the Abdomen

1. Palpation of the Epigastrium

The epigastrium, located below the sternum, is also known as the “heart region.” If it feels hard and painful upon palpation, it indicates a mass in the chest, which is an excess condition; if it feels full but soft and painless, it often indicates a phlegm condition, which is a deficiency condition. If it feels hard and large like a plate, with edges like a spinning cup, it indicates water retention.

2. Palpation of the Abdomen

If abdominal pain is relieved by pressure, it indicates deficiency; if it is aggravated by pressure, it indicates excess.

If the abdomen feels distended and sounds like a drum when tapped, with normal urination, it indicates Qi distension; if it feels like a bag of water and urination is difficult, it indicates water retention.

If there are lumps in the abdomen that feel hard, do not move, and are painful in a specific area, it indicates a mass or accumulation, often due to blood stasis; if the lumps appear and disappear, or feel shapeless and cause pain in an indeterminate area, it indicates a mass or gathering, often due to Qi stagnation. If abdominal pain is around the navel, with lumps in the left lower abdomen, one should consider dry stool. If there is a mass in the abdomen that feels hard and can be moved, it may indicate a parasitic accumulation.

If there is pain in the right lower abdomen, especially if it worsens upon sudden release after deep pressure (known as rebound tenderness in modern medicine), it often indicates intestinal abscess.

Review Questions

1. What are the main aspects of observation diagnosis? What is the significance of “Shen” in observation diagnosis?

2. Why can tongue diagnosis reveal internal changes?

3. What are the clinical significances of changes in tongue quality and coating?

4. How do the clinical significances of tongue quality and coating differ in external diseases?

5. What is the clinical significance of observing children’s fingerprints?

6. What are the main contents of inquiry diagnosis?

7. What major diseases can cause tidal fever? How can one distinguish between exterior and internal cold? How can one differentiate between exterior and internal fever?

8. What are the mechanisms of sweating (normal and pathological)?

9. What is a pulse pattern? What are “Wei, Shen, Gen”? What is their clinical significance?