TCM Diagnosis – Pulse Diagnosis

Everyone is familiar with pulse taking. Whenever we visit a TCM doctor, they will check our pulse and can understand our health condition through this method. Many people are curious about how TCM practitioners can determine our physical state just by feeling our pulse. Today, let’s explore what pulse diagnosis in TCM is.

Pulse diagnosis is a diagnostic method that involves feeling the pulses at different parts of the body to observe the changes in pulse patterns. It is also known as pulse taking, pulse diagnosis, and pulse pressing.

Pulse diagnosis is one of the four diagnostic methods in TCM (observation, listening, inquiry, and palpation), belonging to palpation, and is an essential objective basis for syndrome differentiation and treatment. Palpation is a diagnostic method that has gradually formed through the long-term struggle of the Chinese people against diseases. Although it is the last of the four diagnostic methods, it is the most characteristic of TCM, being the only important diagnostic method that directly touches the patient’s body. Its long history, rich content, and extensive literature make it incomparable to the other three diagnostic methods.

In clinical practice, pulse diagnosis can infer the progress and prognosis of diseases. Clinically, it is essential to master the timing of pulse diagnosis, the patient’s position, the doctor’s finger technique and pressure, and the duration of each pulse check, ensuring that each side’s pulse beats at least 50 times. Additionally, understanding the variations in pulse patterns of healthy individuals is crucial for accurate pulse diagnosis.

Pulse diagnosis involves the doctor using their fingers to press on the patient’s arteries, understanding health or illness by observing the characteristics of the pulse to differentiate diseases.

Pulse diagnosis relies on the sensitive touch of the fingers for experience and recognition. Therefore, learning pulse diagnosis requires familiarity with the basic knowledge of pulse theory and mastery of the fundamental skills of pulse taking, along with repeated practice and careful observation to gradually identify various pulse patterns and effectively apply them in clinical settings.

Let’s review what we have learned previously:

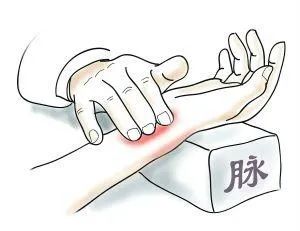

Taking the Cun position is the primary method of pulse diagnosis in TCM.

During pulse diagnosis, the left hand checks the pulse of the right hand, and the right hand checks the pulse of the left hand. The key points for pulse taking can be summarized as: three fingers aligned, middle finger positioned correctly, fingers pressing on the pulse ridge, and finger pressure being moderate.

Characteristics of a normal pulse (Ping Mai):

1. Four to five beats per breath;

2. Not floating or sinking, not large or small, calm and gentle, smooth and strong;

3. All three positions (Cun, Guan, Chi) can be felt, and the pulse is not interrupted when pressed deeply;

The characteristics of a normal pulse include having vitality, spirit, and root, but normal pulses can also show physiological variations influenced by age, gender, body type, lifestyle, emotional state, seasonal climate, time of day, and geographical environment.

As long as there is vitality, spirit, and root, these physiological variations in pulse still belong to the category of normal pulses and should be differentiated from pathological pulses in clinical practice.

The number of pulse patterns varies according to historical medical texts. The Huangdi Neijing records 21 pulse patterns, the Shanghan Zabing Lun records 26, the Mai Jing summarizes 24, the Jingyue Quanshu categorizes them into 16, and the Binhu Maixue lists 27, while the Zhenjia Zhengyan identifies 28 pulse patterns.

Modern clinical references typically mention 28 pulse patterns, and this course will discuss 19 common pulse patterns among them, focusing on position, number, shape, and momentum across eight aspects:

Classified by pulse position: floating and sinking; classified by pulse rate: slow and rapid; classified by pulse width: flooding and thin; classified by pulse length: long and short; classified by pulse strength: weak and strong; classified by smoothness: slippery and rough; classified by evenness: knotted, intermittent, and rapid; classified by tension: wiry, soft, tight, and relaxed, covering the characteristics and clinical significance of nineteen pulse patterns.

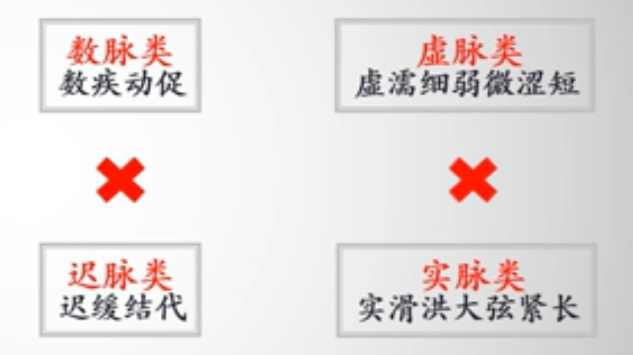

Due to the multitude of pulse patterns, many are very similar and difficult to master and memorize. Therefore, we will categorize and outline the twenty-eight pulses to provide a clearer understanding and simplify the learning process. Next, we will study pulse analogies, composite pulses, and true organ pulses.

Section 5: Pulse Analogies, Composite Pulses, and True Organ Pulses

Yesterday we studied pulse analogies; today we will learn about composite pulses and true organ pulses.

II. Composite Pulses and Their Associated Diseases

[Meaning] This refers to composite pulses (the simultaneous appearance of two or more single-factor pulses).

What are single-factor pulses? Single-factor pulses reflect only one of the four elements: position, number, shape, or momentum. Examples include floating, sinking, slow, rapid, long, short, large, and thin pulses, all of which are considered single-factor pulses.

Composite pulses, such as floating-tight, floating-rapid, floating-slow, sinking-thin, etc., are those where two or more single-factor pulses appear simultaneously.

Additionally, some pulses are inherently composed of several single-factor pulses, such as ru pulse, which is a combination of floating, thin, and soft factors. Se pulse is formed by the combination of thin, slow, and uneven pulse strength.

Why do composite pulses occur?

This is because every disease in clinical practice involves changes in the balance of positive and negative factors, variations in etiology, location, and nature of the disease, which are reflected in the pulse’s momentum, shape, position, and number.

[Causes]Changes in the balance of vital energy, multiple etiologies, and variations in location and nature of the disease.

During pulse diagnosis, it is essential to consider all aspects comprehensively; thus, the pulse patterns observed in clinical practice are generally composite pulses that encompass momentum, shape, position, and number.

What are the principles of composite pulse formation?

[Formation Principles] Any pulse that does not have opposite characteristics can form a composite pulse.

Here are two examples: due to their opposite nature, these two pulses cannot appear simultaneously in one patient:

[Disease Patterns] Composite pulses correspond to the diseases associated with each individual pulse.

Using four common pulse patterns as examples:

Floating Pulse‘s Composite Pulse: Floating indicates exterior

Rapid indicates heat, so floating-rapid pulse indicates exterior wind-heat evil exterior heat syndrome, also known as wind-heat exterior syndrome;

Tight indicates cold, so floating-tight pulse indicates exterior wind-cold evil exterior cold syndrome, also known as wind-cold exterior syndrome;

Slow indicates deficiency, so floating-slow pulse indicates exterior wind evil exterior deficiency syndrome, also known as wind deficiency exterior syndrome.

Sinking Pulse‘s Composite Pulse: Sinking indicates interior

Slow indicates cold, so sinking-slow pulse indicates interior cold syndrome;

Wiry indicates liver disease, so sinking-wiry pulse indicates liver qi stagnation or water retention;

Thin indicates deficiency, so sinking-thin pulse indicates blood deficiency;

Thin indicates deficiency, rapid indicates heat, so sinking-thin-rapid pulse indicates yin deficiency with internal heat;

Rough indicates blood stasis, so sinking-rough pulse indicates blood stasis, often seen in cases of yang deficiency with cold and blood stasis.

Wiry Pulse‘s Composite Pulse: Wiry indicates liver disease, pain, phlegm retention

Tight indicates cold, pain, so wiry-tight pulse is often seen in cold stagnation in the liver pulse;

Rapid indicates heat, so wiry-rapid pulse indicates liver qi transforming into fire or liver-gallbladder damp-heat, liver yang rising;

Thin indicates deficiency, rapid indicates heat, so wiry-thin-rapid pulse indicates liver and kidney yin deficiency;

Slippery indicates phlegm dampness, food accumulation, excess heat, rapid indicates heat, so wiry-slippery-rapid pulse is often seen in liver fire with phlegm, liver-gallbladder damp-heat or liver yang disturbing, phlegm-heat retention;

Thin indicates deficiency, so wiry-rapid pulse indicates liver blood deficiency or liver qi deficiency and so on.

Rapid Pulse‘s Composite Pulse: Rapid indicates heat

Slippery indicates phlegm retention, food accumulation, excess heat, so slippery-rapid pulse indicates phlegm-heat, excess heat, or food accumulation with internal heat;

Flooding indicates excess heat, so flooding-rapid pulse indicates excess heat syndrome, often seen in cases of exterior heat disease;

Thin indicates deficiency, so thin-rapid pulse indicates yin deficiency with excess fire.

That concludes our discussion on composite pulses and their associated disease patterns. Finally, let’s learn about true organ pulses.

III. True Organ Pulses

True organ pulses are pulses that appear during the critical phase of a disease and are characterized by the absence of vitality, spirit, and root.

True organ pulses typically indicate severe pathogenic factors, depletion of vital energy, loss of stomach qi, and critical illness, also known as failure pulse, absolute pulse, dead pulse, or strange pulse.

[Content]

1. Absence of Vitality Pulse: Characterized by a lack of harmony, with a firm and bounding pulse. Examples include Yanda pulse, Zhuan Dou pulse, Dan Shi pulse;

2. Absence of Spirit Pulse: Characterized by disordered pulse rate and chaotic pulse shape. Examples include Que Zhuo pulse, Wu Lou pulse, Jie Suo pulse, Ma Cu pulse;

3. Absence of Root Pulse: Characterized by a weak or unresponsive pulse. Examples include Fu Fei pulse, Yu Xiang pulse, Xia You pulse.

Although true organ pulses are seen in critically ill patients, with the continuous advancement of medical technology and ongoing research and clinical practice, there is a new understanding of true organ pulses. Some are caused by organic heart disease, but they are not necessarily hopeless signs of death; careful observation and efforts to treat should be made.

The Huangdi Neijing states: “The meridians are the pathways that can determine life and death, manage all diseases, and regulate deficiency and excess; they must be unobstructed.” This means that pulse diagnosis can determine a patient’s life and death, manage various diseases, and regulate deficiency and excess.

The Huangdi Neijing also states: “A good diagnostician observes color and feels the pulse, … weighing and measuring to understand the disease’s main organ, observing the floating and sinking to know the cause of the disease.” This means that from the pulse’s characteristics, one can identify the main organ affected by the disease; from the patient’s pulse, one can discern the cause of the disease.

This concludes our study of pulse analogies, composite pulses, and true organ pulses for this section.

Long press to recognize the QR code and follow Xile Liangyao

Let’s discover the wonders of TCM together and bring TCM closer to life.