Pulse diagnosis, which includes both pulse examination and palpation, is a method used by practitioners to assess a patient’s condition through touch at specific body locations. Pulse diagnosis is a primary means of diagnosing diseases in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM).

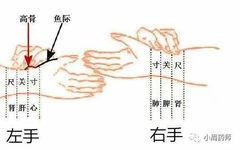

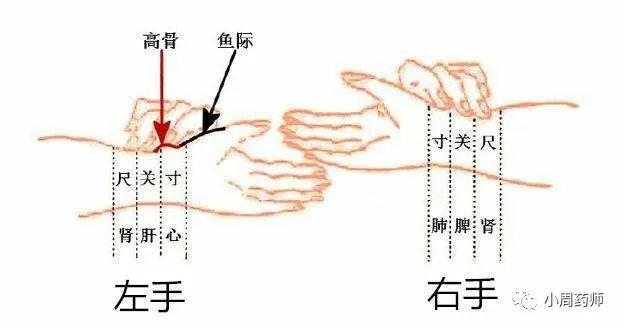

(1) Locations of Pulse Diagnosis and Assessment of Zang-Fu Organs Pulse diagnosis, also known as “qie mai” (切脉) or “hou mai” (候脉), is a diagnostic method where the physician uses their fingers to palpate the patient’s arteries to explore the pulse and understand changes in the patient’s condition. 1. Locations for Pulse Diagnosis The commonly used location for pulse diagnosis is the “cun kou” (寸口), which refers to the superficial area of the radial artery at the wrist. “Cun kou” is also known as “qi kou” (气口) or “mai kou” (脉口) and is divided into three sections: cun (寸), guan (关), and chi (尺). The location of the high bone of the palm (radial styloid) is referred to as “guan”, the area before the guan (at the wrist) is “cun”, and the area behind the guan (at the elbow) is “chi”. Each hand has three sections: cun, guan, and chi, totaling six pulses. The reason TCM employs the “cun kou diagnosis method” is that the pulse at this location can reflect the changes in the five zang organs and six fu organs. Firstly, this is because the cun kou pulse is a major junction of the hand taiyang lung meridian, where the meridians of the five zang and six fu organs converge, as the saying goes, “the lung governs all pulses”. Secondly, the foot taiyin spleen meridian connects with the hand taiyang lung meridian, and the hand taiyin lung meridian originates from the middle jiao (spleen and stomach), which is the source of qi and blood for all zang and fu organs. Therefore, the condition of the qi and blood in all the zang and fu organs can be reflected from the cun kou pulse. 2. Assessment of Zang-Fu Organs from Cun Kou Pulse

2. Assessment of Zang-Fu Organs from Cun Kou Pulse

Regarding the assessment of the three sections of the pulse and their corresponding zang-fu organs, there have been many discussions throughout history, but the basic principles are consistent. The commonly used classification method in clinical practice is: right cun corresponds to the lung, right guan corresponds to the spleen and stomach, right chi corresponds to the kidney (mingmen), left cun corresponds to the heart, left guan corresponds to the liver, and left chi corresponds to the kidney. Overall, this reflects the principle of “upper (cun pulse) assesses the upper (upper body), lower (chi pulse) assesses the lower (lower body)”. This has certain reference significance in clinical practice, but one should not mechanically interpret the method of assessing the zang-fu organs from the three sections; it is necessary to analyze the specific conditions of the disease comprehensively to arrive at a more accurate diagnosis. Additionally, the cun kou pulse is also the easiest to palpate, which is one reason for its exclusive use in pulse diagnosis.

When performing pulse diagnosis, the patient should be seated or lying supine, with the arm at approximately the same level as the heart, and the wrist should be extended with the palm facing up to facilitate smooth blood flow.

For adults, the pulse is located using three fingers: first, the middle finger is placed on the high bone of the palm to locate the guan, then the index finger is placed in front of the guan to locate the cun, and the ring finger is placed behind the guan to locate the chi. The three fingers should be arranged in an arc shape, with the fingertips level, making contact with the pulse. The spacing of the fingers should correspond to the patient’s height; taller individuals should have a wider spacing, while shorter individuals should have a closer spacing. For children, the cun kou pulse area is very short, and it is not possible to use three fingers to assess cun, guan, and chi; instead, the “one-finger (thumb) method” can be used to locate the guan without subdividing into three sections.

During pulse diagnosis, three different levels of pressure are often used to assess the pulse: light pressure on the skin is for “floating” (ju), heavy pressure down to the bones is for “sinking” (an), and moderate pressure on the muscles is for “medium” (xun). Each of the three sections (cun, guan, chi) has floating, medium, and sinking assessments, collectively referred to as “three sections and nine assessments”.

Simultaneous palpation of all three fingers is called “total palpation”, which is a common method in pulse diagnosis. To focus on understanding a specific pulse, one finger can be used for single palpation, known as “single palpation” or “single diagnosis”. In clinical practice, total palpation and single diagnosis are often used in conjunction.

During pulse diagnosis, a quiet internal and external environment is necessary. If the patient has just engaged in significant activity, they should be allowed to rest for a moment before pulse diagnosis.

The practitioner must breathe evenly and calmly, maintaining a serious attitude and concentrating on the pulse under their fingers. The duration of each pulse diagnosis should not be less than fifty beats according to ancient texts, and in modern clinical practice, it should not be less than one minute.

The main purpose of pulse diagnosis is to observe the pulse characteristics. The so-called pulse characteristics refer to the manifestations of the pulse under the fingers, including frequency, rhythm, fullness, location, smoothness, and amplitude of fluctuation. By observing changes in the pulse characteristics, one can discern the location, nature, and the state of the pathogenic factors.

3. Characteristics and Variations of the Normal Pulse

The normal pulse, also known as “ping mai” (平脉) or “chang mai” (常脉), has a standard count of one breath in and out corresponding to four pulse beats. The pulse is gentle yet strong, calm and rhythmic, neither fast nor slow, and varies normally with physiological activities and environmental conditions.

In pulse theory, the normal pulse has three main characteristics: first, it is “spirited” (you shen), meaning the pulse is gentle yet strong; second, it has “stomach qi” (you wei), meaning the pulse comes and goes smoothly and rhythmically; third, it has “root” (you gen), meaning that even with heavy pressure at the chi section, there remains a calm and strong response.

The pulse characteristics are closely related to the internal and external environments of the body. Due to differences in age, gender, constitution, and mental state, the pulse may undergo certain physiological changes. For example, younger individuals tend to have faster pulses, infants have rapid pulses, strong young adults have more forceful pulses, and elderly individuals have weaker pulses. Adult females generally have slightly faster and softer pulses compared to adult males. Taller individuals tend to have longer pulse manifestations; shorter individuals have shorter manifestations.Thin individuals often have slightly floating pulses; overweight individuals often have slightly sinking pulses.Heavy physical labor, intense exercise, long-distance walking, drinking alcohol, overeating, or emotional excitement can lead to faster and stronger pulses; while hunger can result in weaker pulses. Seasonal changes also affect pulse characteristics; for instance, in spring, the pulse may be slightly wiry, in summer, slightly surging, in autumn, slightly floating, and in winter, slightly sinking. These variations should be noted in clinical pulse diagnosis to differentiate from pathological pulses. Some individuals may not have a pulse detectable at the cun kou but may have a slanted pulse towards the back of the hand from the chi section, known as “xie fei mai” (斜飞脉); if it appears on the dorsal side of the cun kou, it is called “fan guan mai” (反关脉), both of which are anatomical anomalies of the radial artery and are considered physiological peculiarities, not pathological pulses.

Practice Questions: 1. After drinking alcohol, the pulse is often A. slightly floating B. slightly sinking C. fast and strong D. slightly wiry E. slightly surging Answer and Explanation: 1. C This question examines the characteristics and variations of the normal pulse. The pulse characteristics are closely related to the internal and external environments of the body. Due to differences in age, constitution, and mental state, the pulse may undergo certain physiological changes. For example, thin individuals often have slightly floating pulses (A incorrect), overweight individuals often have slightly sinking pulses (B incorrect). Heavy physical labor, intense exercise, long-distance walking, drinking alcohol, overeating, or emotional excitement can lead to faster and stronger pulses (C correct), while hunger can result in weaker pulses, etc. Seasonal changes also affect pulse characteristics; for instance, in spring, the pulse may be slightly wiry (D incorrect), in summer, slightly surging (E incorrect), in autumn, slightly floating, and in winter, slightly sinking.Master Zhou’s Commentary:This section is brief; understanding the locations for pulse diagnosis and the assessment of zang-fu organs from the cun kou is sufficient. The pulse characteristics mainly focus on the relationship between changes in the internal and external environments and the pulse characteristics. Taller individuals tend to have longer pulse manifestations; shorter individuals have shorter manifestations. Thin individuals often have slightly floating pulses; overweight individuals often have slightly sinking pulses. Heavy physical labor, intense exercise, long-distance walking, drinking alcohol, overeating, or emotional excitement can lead to faster and stronger pulses; while hunger can result in weaker pulses.