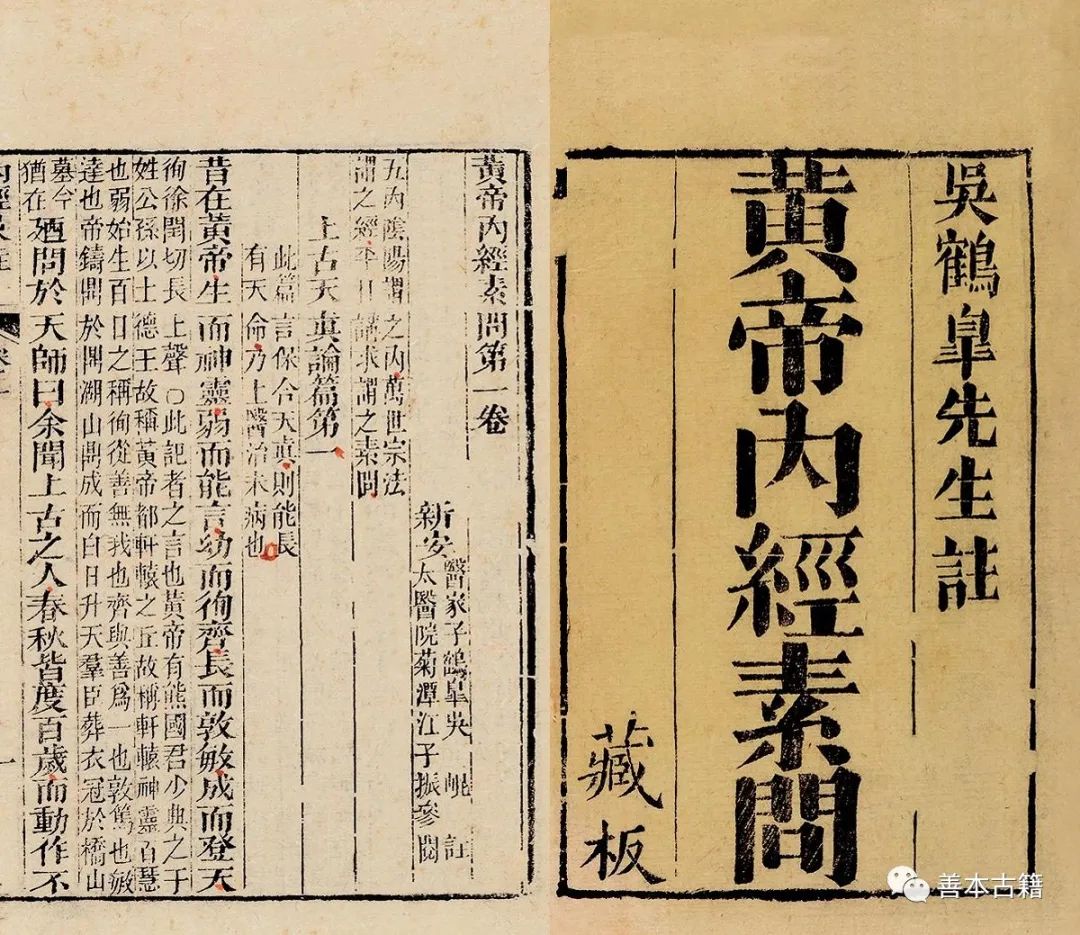

The Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon) is the most important classic work in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), establishing the academic foundation for the development of TCM. This is a consensus in the academic community throughout history. So, why does the Huangdi Neijing hold the top position among medical classics? What is the enduring charm and uniqueness that sets it apart from other TCM texts? To begin with, the conclusion is thrown out: the Huangdi Neijing is a sage book that conveys the Dao through medicine. This conclusion is presented in a decisive manner, mimicking the style of the Huangdi Neijing. After reading several sage books, one can understand that their basic style is to present conclusions without providing the process of argumentation, with every word and sentence being resolute, urging people to understand and act accordingly, without explaining why this understanding or action is necessary. However, while the Huangdi Neijing is a sage book, this article is not a sage text, so it needs to provide arguments for the conclusion presented. First, the meaning of a sage book will be explained, followed by a point-by-point argument on why the Huangdi Neijing is a sage book that conveys the Dao through medicine.

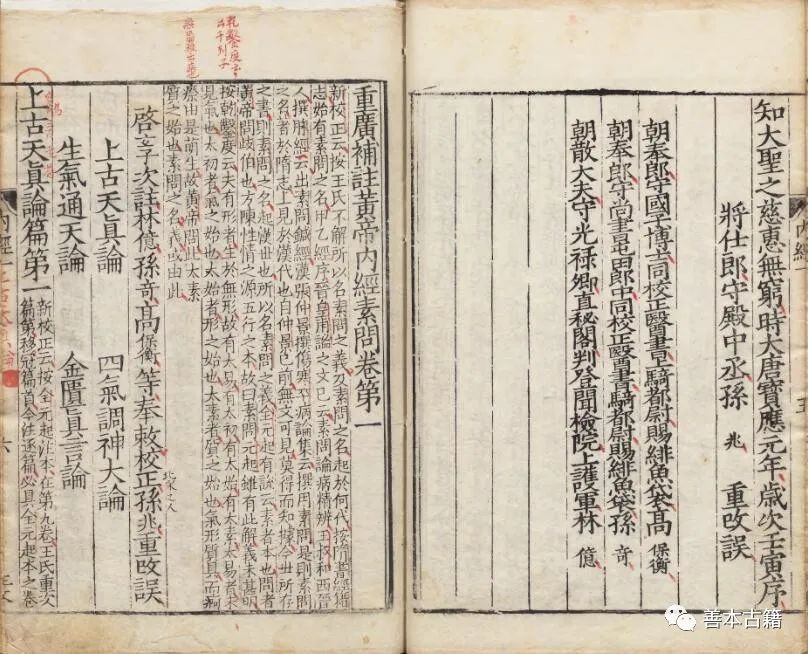

A sage book is one that is in accordance with the “Dao”. The so-called “Dao”, in modern language, can be understood as the source and laws of the universe’s operation. An author who can write a book in accordance with the “Dao” must be a person who understands the “Dao”, that is, a sage. What kind of person can be called a sage? The Suwen (Plain Questions) of the Huangdi Neijing provides a detailed explanation, and how one can become a sage is also clearly discussed in that text, which is through cultivation. Therefore, a sage, in modern terms, is a person who has achieved success in cultivation. In summary, a sage book is one written by a person who has achieved success in cultivation and can reach the source and laws of the universe’s operation. The Huangdi Neijing delves into the “Dao” through medicine, thus it is a sage book that conveys the Dao through medicine. The title: the character “Nei” (Inner) has significance. Among various ancient texts, many that are titled “Jing” (Classic) are sage books. The term “Jing” is not something that can be casually applied to any book. For example, the Buddhist Xinjing (Heart Sutra), the Daoist Daodejing (Tao Te Ching), the Confucian Yijing (I Ching), the martial arts Quan Jing (Classic of Boxing), and the medical Nanjing (Classic of Difficulties) are all highly respected and considered peak works in their respective fields. Of course, there are also books that are falsely titled as “Jing” and do not live up to the name, and some even fake their status. In fact, it is precisely because works titled “Jing” have a high academic status, even a sacred connotation, that some authors, seeking fame, attempt to mix in with the genuine, using the aura of “Jing” to steal a reputation, or even commit fraud. What significance does the character “Nei” in the Huangdi Neijing have? This article will make some speculations based on the academic content of this book. Ancient texts such as Chajing (Classic of Tea), Shuijing (Classic of Water), and Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas) are all related to their content by their titles. By this measure, the Huangdi Neijing seems to be more appropriately called the “Huangdi Medical Classic”, but it is not titled “Medical Classic” but rather “Inner Classic”, which seems to indicate that the content of this book not only includes medicine but also involves various aspects of the human body internally. According to the academic thought of the Huangdi Neijing of the unity of heaven and man, the human body is a small universe, and exploring the changes in the human body is actually exploring the changes in the universe, but this is an internal exploration, unlike the Shuijing and Chajing which explore externally. In summary, the character “Nei” seems to express the perspective of this book’s exploration of issues, implying that this book discusses the Dao of the universe from an internal perspective. Of course, this may seem like a stretch, but it is also possible that this is its original meaning. However, there is also a Huangdi Waijing (Outer Canon), and using this logic to explain the character “Wai” does not hold. Many scholars believe that the Huangdi Waijing is a pseudo-classic, using the title of the Huangdi Neijing to enhance its status. This seems plausible. The academic value of the Huangdi Waijing is far inferior to that of the Huangdi Neijing, and the dialogues in the book, besides those involving the Yellow Emperor, Qibo, and Leigong, also include a motley crew of court officials and relatives, which does not seem credible. The authorship: the standard of “sage” The authors of sage books are not ordinary authors; they must be sages. The Huangdi Neijing places great importance on and emphasizes the sage identity of its authors. The opening sentence of this great work states: “In ancient times, the Yellow Emperor was born with divine spirit, could speak in infancy, was wise in youth, and became enlightened in adulthood.” This sentence comes from the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun (On the True Nature of Ancient Times). The opening sentence clearly states that the author is not an ordinary person but a sage. It also points out that the Yellow Emperor is not a sage who has achieved cultivation but is a sage by birth. This opening is indeed unusual! It directly tells the reader: everyone, this book is written by a sage.

The Shanggu Tianzhen Lun devotes considerable space to introducing the sage. It categorizes sages into four types: true person, supreme person, sage, and virtuous person, explaining their behavioral characteristics and lifespan. Notably, it also explains how one can become one of these four types of sages. For the highest level of true person, the description in the text is: “The Yellow Emperor said: I have heard that in ancient times there were true persons who could manipulate heaven and earth, grasp yin and yang, breathe in essence, guard their spirit, and their muscles were unified, thus they could live long enough to cover heaven and earth, without an end; this is their Dao of life.” The phrases “breathe in essence, guard their spirit, muscles unified” are the original expressions and theoretical foundations of the core content of TCM Qigong cultivation, which is a skill of cultivation that embodies the unity of heaven and man, body and mind. This indicates that the method and path to becoming a sage is through cultivation. The classification of true, supreme, sage, and virtuous persons depends on the level of cultivation achieved. The true person is the highest level of cultivation achievement. “This is their Dao of life” means reaching the level of the “Dao”. A close reading of the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun reveals that its writing logic is very meticulous. After introducing the sage identity of the Yellow Emperor in the first sentence, the first question he asks Qibo is: “I have heard that ancient people lived to be over a hundred years old and did not decline in their actions; why do people today decline at fifty? Is it due to the times or is it a loss on the part of people?” Qibo answers based on the health-preserving methods of ancient people. Next, the Yellow Emperor asks about the lifespan of humans, and Qibo responds with various principles. These two segments discuss ordinary people, that is, the natural lifespan and health preservation of common people. Only then does the Yellow Emperor talk about sages. Please pay special attention: this segment about true, supreme, sage, and virtuous persons is the Yellow Emperor’s monologue. At this point, he has set Qibo aside. Here, the Yellow Emperor speaks about the Dao of sages from the perspective of a sage, emphasizing the authenticity of these words. This writing structure fully demonstrates that the Yellow Emperor understands ordinary people and sages, first discussing ordinary people and then sages, clearly conveying the main theme of this text, which is aimed at transcending the ordinary and entering the sacred. As the first chapter of the Huangdi Neijing, the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun hardly discusses medicine. If the discussion of ordinary people’s health preservation can be considered preventive medicine, the sage’s path of cultivation almost completely transcends medicine. This indicates that the academic viewpoint the chapter wants to express is: the ultimate goal of all medicine is to achieve transcendence through health preservation and cultivation; treating diseases is not the most important thing. The text has already stated: “The teachings of the ancient sages all say to avoid the ‘evil winds’ and ‘harmful influences’ at the right times, to be tranquil and void, to let the true qi flow, and to guard the spirit within; how can illness arise?” This means that when the cultivation of health preservation reaches a certain level, there will be no illness, and thus nothing to treat. Therefore, the “Dao” contained in the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun is the path to transcendence. It encompasses medicine yet transcends medicine, conveying the Dao through medicine. However, in modern society, not many people recognize the authenticity of the path to transcendence; mainstream views either regard it as mystical, or as a form of martial arts medicine, or simply as superstition. The main purpose of this article is to reveal the original intention of the Huangdi Neijing, not to evaluate it. However, as mentioned earlier, at the end of this article, some reference ideas will be provided to understand its original intention in conjunction with modern scientific progress. Content: Conveying the Dao through medicine, integrating medical Dao.

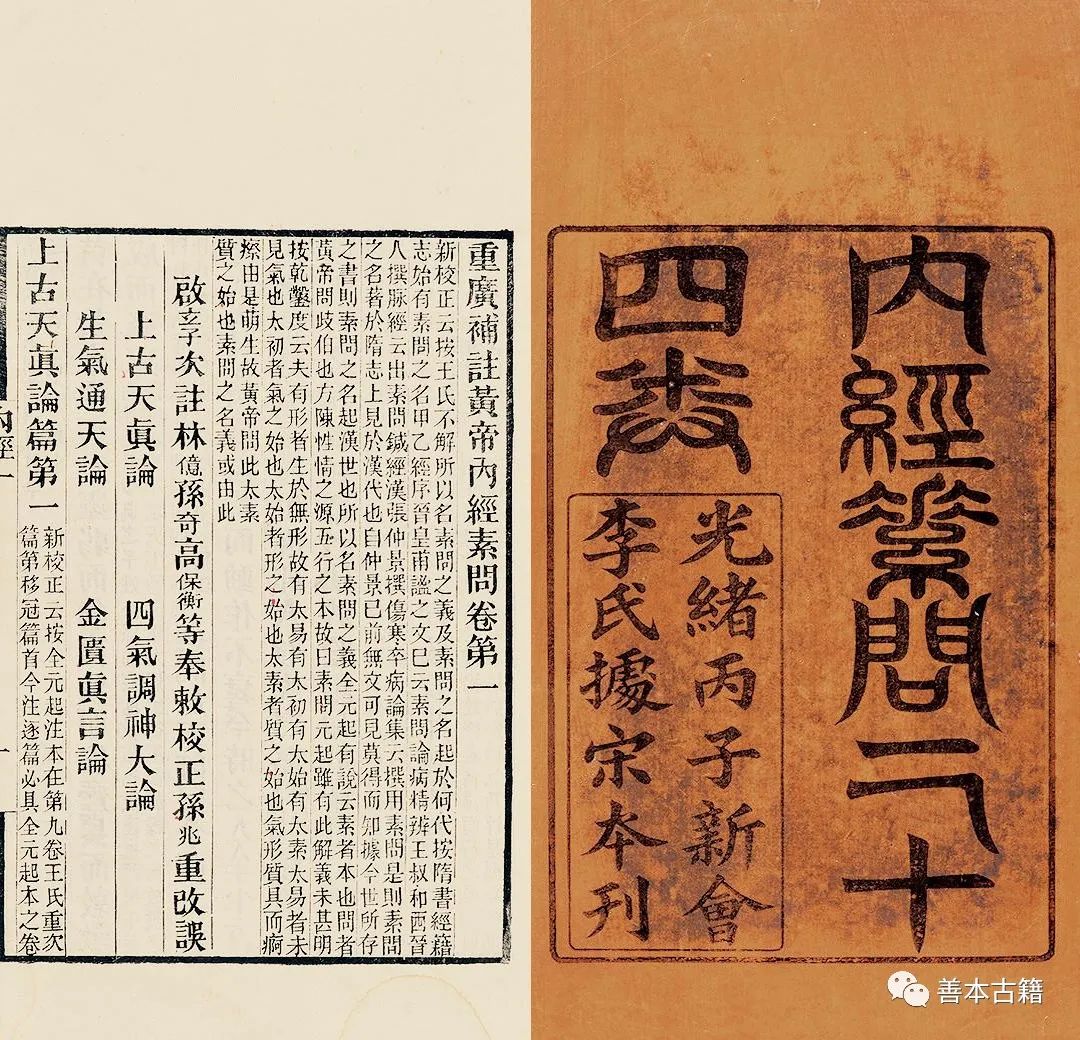

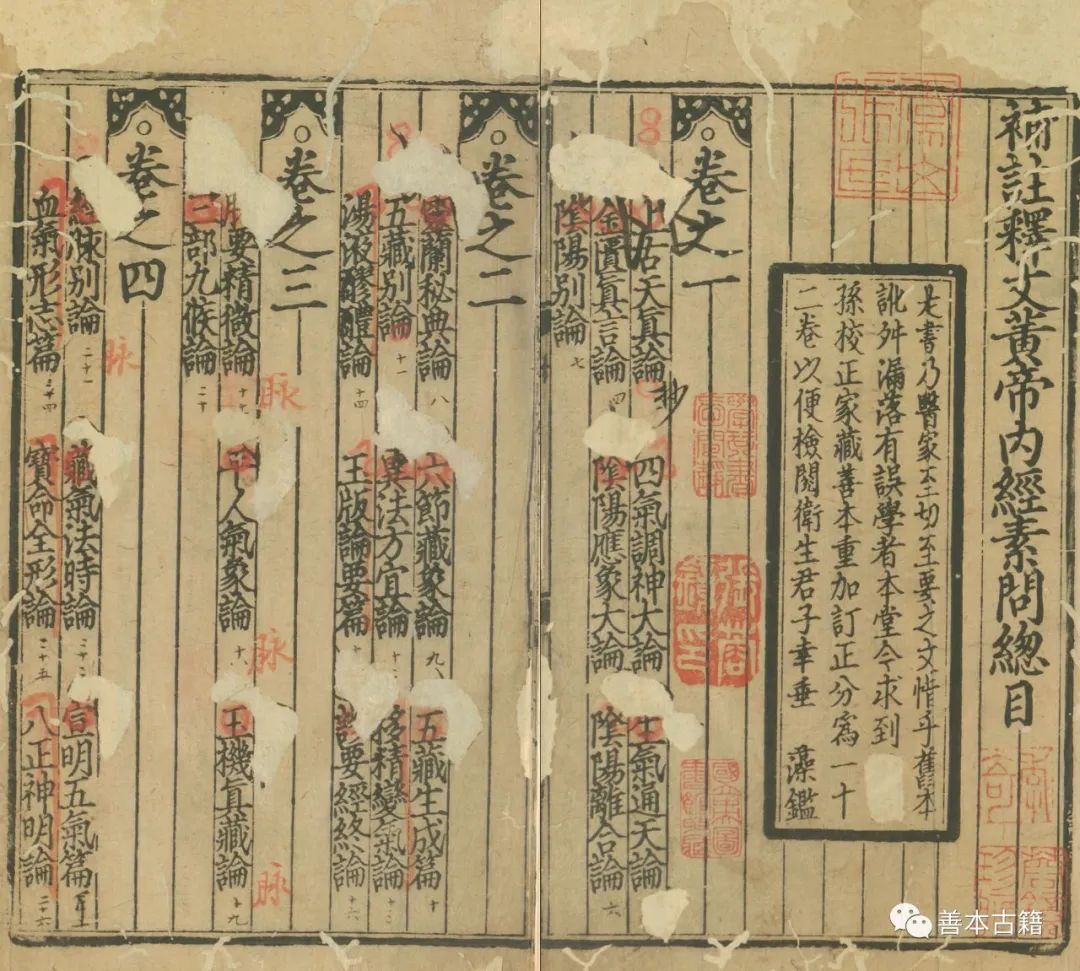

The Huangdi Neijing consists of approximately 140,000 words in total, combining the Suwen and Ling Shu, which does not qualify as a lengthy work, yet its content spans astronomy, geography, and human affairs, being rich and broad. Due to space constraints, this article cannot explore all the content of the Huangdi Neijing in detail. The following will first explore the academic thought of its overall content, and then discuss the academic characteristics of its core content. The Wang Bing edition of the Huangdi Neijing contains a total of 24 volumes and 81 chapters, with the majority of his additions being seven major discussions on the theory of the five movements and six qi, which occupy more than one-third of the entire Suwen. Besides these seven chapters, there are also several discussions on the theories of yin-yang and the five elements, the correspondence between heaven and man, and the path to transcendence, such as the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun, Siqi Tiaoshen Dalu Lun, Shengqi Tongtian Lun, Yifa Fangyi Lun, Yijing Bianqi Lun, Yin Yang Yingxiang Dalu Lun, and Yin Yang Lihe Lun. Although precise word counts have not been conducted, it is not difficult to estimate that the total word count of these chapters exceeds half of the entire text. Why are these chapters singled out? Because from a modern scientific perspective, the content of these chapters largely falls within the realms of astronomy, geography, climatology, phenology, anthropology, and philosophy; they may have some relation to epidemiology, but they do not have direct connections to the subjects of anatomy, histology, physiology, pathology, or biochemistry, which are formally taught in medical schools. Based on this, it can be inferred that the content of the entire book that aligns with modern medical categories is even less than half. In other words, viewed from a modern perspective, this great work that laid the foundation for the development of TCM seems to spend more than half of its content discussing matters outside of medicine. It does not resemble a purely medical theoretical monograph. However, this is merely an analysis from the perspective of modern science; if viewed from the perspective of TCM itself, these contents are all organic components of its theoretical system. Moreover, if one were to look at the content of modern medical disciplines through the lens of TCM, one would find that they primarily discuss “techniques” without addressing the “Dao”. TCM is a study of human health and disease. In the worldview of TCM, a person is not an individual separated from the universe; rather, they are a “small universe”. Each person is a holographic reflection of the universe, and their life, aging, illness, and death are closely related to the development and transformation of the universe. To learn and understand the knowledge and laws of human health and disease, one must know the overall knowledge and laws of the universe’s operation. This is the TCM perspective of the unity of heaven and man. The so-called conveying the Dao through medicine, what Dao is being conveyed? It is the Dao of the unity of heaven and man, which means aligning the medical “techniques” with the heavenly “Dao”. The theories of yin-yang and the five elements, the five movements and six qi, the correspondence between heaven and man, and the path to transcendence are all important focal points and handles of the Dao of the unity of heaven and man. The words and phrases of these theories reflect the influence and role of the “Dao”, expressing the interrelationship between humans and nature, especially illustrating how the operation of heaven and earth affects humans. Without these theories as a foundation and support, understanding the “Dao” becomes even more difficult. Because pure “Dao” belongs to the “metaphysical”, it is difficult to express in words or write in books. Therefore, grasping the academic thought of the Huangdi Neijing requires first reading the entire book. Selective reading must be based on thorough reading. Otherwise, it is easy to lose the “Dao” part while emphasizing the “technique” part. Especially if the editors of selective readings only follow modern medical perspectives, lacking the worldview and understanding of the human body from TCM itself. For example, when selecting the Zhi Zhen Yao Da Lun, one might overlook the content of the theory of movements and qi, focusing instead on the “Nineteen Pathogenic Mechanisms”. The “Nineteen Pathogenic Mechanisms” are indeed important, but without the theory of movements and qi, they become like water without a source, a tree without roots. The great poet Lu You of the Southern Song Dynasty once said: “If you truly wish to learn poetry, your effort lies outside of poetry.” Learning poetry is like learning TCM. Using this metaphor, the “Nineteen Pathogenic Mechanisms” are like the “Inner”, while the theory of movements and qi is like the “Outer”. TCM theory includes numerous theories such as yin-yang and the five elements, the five movements and six qi, and the theory of organs and meridians, which can be said to be the core content of TCM theory. It is equivalent to the sum of modern medical anatomy, histology, physiology, biochemistry, and pathology, expressing TCM’s unique understanding and grasp of the human body. So, what was the ancient thought in constructing the theory of organs and meridians? In short, it was to jump out of the “metaphysical” and into the “metaphysical”. The “metaphysical” is the world of forms, emphasizing structural forms. The “metaphysical” is the world of qi, emphasizing the operation of qi. In other words, the ancients did not fail to see the “techniques”; rather, they saw through the “techniques” to the “Dao” behind them. The Dao of the unity of heaven and man posits that the qi operation of the universe influences the qi operation of the human body, and the qi operation of the human body influences the functional activities of the organs, meaning the “Dao” governs the “techniques”. TCM recognizes that both the qi operation of the human body and that of the universe are living and interconnected. The theory of organs and meridians was established based on the qi operation of living beings and the living universe. This approach to understanding and grasping the human body maintains the original ecology of life itself without being destructive. If one were to adopt the anatomical structural approach, it would be difficult to achieve this. It is precisely by following this thought that the meridians were discovered. Otherwise, in today’s highly developed modern science, how could meridians not have been discovered? A special reminder: when discussing meridians, people often think of the lines and points on meridian charts, but meridian charts are merely imagined, representing the result of interpreting the texts with figurative thinking; the relevant texts in the Ling Shu do not mention lines or points. In reality, meridians are more like the flight paths of airplanes; they are merely the trajectories of flight, and there are no specific lines in the sky. In other words, meridian points do not exist as specific organizational structures; they are formless, existing in the “metaphysical”. Modern anatomy is sufficiently detailed, yet it still has not found the organizational structure of meridians. Of course, it is pointed out that the TCM theory of organs and meridians is established from a “metaphysical” perspective, but this does not deny or overlook the existence of the “metaphysical”. In fact, the “metaphysical” can encompass the “metaphysical”, but the “metaphysical” does not necessarily encompass the “metaphysical”. For example, discussing the qi operation of the heart or lungs certainly involves the specific “metaphysical” organs of the heart and lungs; however, if one only focuses on the structural forms of the heart and lungs, how can one discover the Hand Shaoyin Heart Meridian and Hand Taiyin Lung Meridian? In summary, whether in overall content or core content, the academic thought of the Huangdi Neijing is to convey the Dao through medicine, integrating medical Dao. If one does not see this point, it is difficult to claim to have understood the essence and original intention of this great work. Writing Style: The Authority Behind the Decisive Conclusion The writing style of the Huangdi Neijing has a prominent characteristic: it presents conclusions without explanations, or very few explanations. Therefore, all viewpoints seem to appear out of nowhere, suddenly striking the reader. This is a commanding, authoritative writing style: everything is stated decisively, leaving no room for debate. Such a writing style is common in ancient texts historically referred to as “Jing”. For example, the Daodejing begins with “The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao; the name that can be named is not the eternal name”; but why is the Dao not the eternal Dao, and the name not the eternal name? It does not explain. Similarly, in the Xinjing: “Form is not different from emptiness, emptiness is not different from form; form is emptiness, emptiness is form”; why are form and emptiness not two? It does not explain. Not only are Chinese ancient texts like this, but foreign texts also exhibit similar expressions. For instance, such expressions are common in the Bible. This writing style gives the impression of extreme certainty, as if what is being expressed is indisputable truth. Why do “Jing” texts adopt such a writing style? This article believes that the most important reason is that the “Dao” itself is difficult to convey in words. The “Dao” is “metaphysical”; all knowledge that can be expressed in words belongs to the “metaphysical”. The “metaphysical” things are invisible and intangible, except for sages who can perceive them to varying degrees, while the masses know nothing of them. Even if the author, being a sage, wishes to clarify and convey their original intention to the public, what can they say? Imagine if you were responsible for introducing something that people have never heard of, something invisible and intangible; how would you introduce it? Your final choice might also be: just state the conclusion, after all, I believe it, and to be honest, whether you believe it or not is up to you. Therefore, it is not that the authors of the Huangdi Neijing wish to be mysterious or secretive, but rather that they have no choice. However, if the reader also possesses the level of a sage, that is, has the relevant cultivation foundation, they can grasp the subtlety of the “Dao”; thus, conveying information related to the “Dao” is not difficult. For example, one can simply smile while holding a flower. Therefore, it can be seen that the adoption of this authoritative writing style in sage books has its inherent and necessary reasons. However, it is precisely this writing style that leaves a vast space for interpretation for future generations. Since the authors do not explain, others will certainly interpret, as the general readers have a strong need for interpretation. Thus, it is well-known that countless later generations have interpreted various classics. It is also quite interesting that since the authors do not explain, no matter who interprets, it will not be the standard answer. Therefore, despite the multitude of commentaries, the true meaning of the classics will almost never have a definitive conclusion. This is one of the unique charms of classics and one of the reasons for their enduring vitality. Discussion: Unveiling the Veil Over the “Dao” History is constantly progressing. In the era of the Huangdi Neijing, the “Dao” that was invisible, intangible, and unspeakable, can we say something about it today in the context of modern science? Yes! Especially with the new achievements in modern physics, some veils over the “Dao” can be unveiled. However, this topic is too vast to be expanded here; it can only be addressed in a small way. Over the past century, from the theory of the Big Bang to string theory, physicists have conducted a series of fruitful explorations into the origins and laws of the universe’s operation. Although these theories still carry a hypothetical nature and require further verification, they have greatly enriched humanity’s understanding of the ultimate existence of things. The Big Bang theory posits that the universe was formed from a dense, hot singularity that expanded after a Big Bang. In the extremely short time at the beginning of the Big Bang, matter could only exist in the form of fundamental particles such as neutrons, protons, electrons, photons, and neutrinos. String theory suggests that these fundamental particles are not point-like particles but rather small segments of “energy strings”. In short, these two far-reaching scientific hypotheses suggest that the essence of all things in the universe initially exists in the form of energy. If one can view TCM through the lens that the essence of things is in the form of energy, understanding the academic content of TCM’s theoretical system becomes relatively easy. For example, the TCM concept of “qi” can be understood as the energy form of life. According to the TCM monism worldview, all things in the universe gather to form shapes and disperse to become qi; gathering is “metaphysical”, dispersing is “metaphysical”; the two transform into each other, which is very similar to the modern physics concept of the mutual transformation of matter and energy! TCM treatment aims to regulate the qi operation system of the human body, which is the theory of organs and meridians. It has been previously mentioned that establishing this system is not approached from the “metaphysical” but rather from the “metaphysical”. The so-called balance of yin and yang, the balance of yin and yang, is the balance of qi operation, which directly affects the balance of life energy forms, rather than directly focusing on the adjustment of life structural forms. If one uses the structural approach emphasized by Western medicine to “regulate” TCM, it would be akin to binding TCM with foot-binding, restricting its development trajectory. The structural approach is not wrong to use in studying TCM, but if it is regarded as the only or essential research approach, it would lead TCM to a path of compromise and hindered progress! TCM should strive for self-strengthening, developing its own research approach focused on the operation of life energy to achieve its modernization. In fact, in terms of scientificity, modern medicine, or Western medicine, has already lagged far behind the current perspectives and achievements in the scientific field. Generally speaking, it can be said that contemporary physicists’ understanding of things has already reached the era of Hawking, while contemporary medical practitioners’ understanding remains stuck in the era of Newton. In the 21st century, while physicists are exploring string theory and proposing that the ultimate composition of things is “energy strings”, 21st-century medical practitioners are still discussing genetic modification and striving to adjust the subtle structures of the human body. Focusing on structure is not wrong, but if one cannot see the energy operation foundation that supports the structure, at least it is incomplete and not comprehensive. Returning to the Huangdi Neijing, let us say a few words about the sage theory in the Shanggu Tianzhen Lun. When reading that the true person is “longevity covering heaven and earth, without an end”, readers should be able to associate that this form of existence can only be in the form of energy, not structural form. Is there a basis for this statement? Here, the cultivation processes of Buddhism and Daoism can serve as references. The four stages of Daoist cultivation are: refining essence into qi, refining qi into spirit, refining spirit into void, and refining void into unity with the Dao, achieving the Yang Spirit. Buddhist cultivation, taking the nine stages of meditation as an example, begins with the four meditative absorptions, then the four formless absorptions, and finally the cessation of all phenomena, achieving the Dharma body. Both cultivation paths transition from existence to non-existence, that is, from “metaphysical” to “metaphysical”. If we replace existence and non-existence with modern scientific concepts, it can be understood as transforming the existence of life structural forms into the existence of life energy forms. The so-called Qigong is the practice of cultivating life energy forms. The conclusion of this article regarding the above discussion of the “Dao” and modern science is: the academic thought of the Huangdi Neijing still has vast space for in-depth exploration even in modern times, even in the context of modern scientific backgrounds. As a sage book that conveys the Dao through medicine, it transcends time. This is not surprising; shouldn’t sage books be like this? (Liu Tianjun)

If you wish to participate in discussions related to ancient texts, please reply to the WeChat public account message: Group Chat

Welcome to join the community for learning and exchanging knowledge about ancient texts.