The Rú Mài (濡脉) is soft and fluffy, often lacking clear boundaries, while the Xì Mài (细脉) is as thin as a thread. What exactly is the Rú Xì Mài? Is it both soft and fine? Does it resemble a thin line but feel weak and fluffy? This seems a bit difficult to imagine.

I recall reading in a pulse diagnosis book that the Rú Mài is like cotton floating on water and as fine as a thread, indicating dampness. This description has always been hard for me to understand.

However, a recent case has helped me grasp the concept of the Rú Xì Mài.

A 30-year-old female patient presented with severe hair loss for about two months. She reported fatigue, easy exhaustion, a bitter taste in her mouth, poor sleep with frequent awakenings, occasional lower back soreness, and normal bowel and urinary functions. She mentioned significant work-related stress. Her complexion appeared slightly yellow, and her fingers looked somewhat thick.

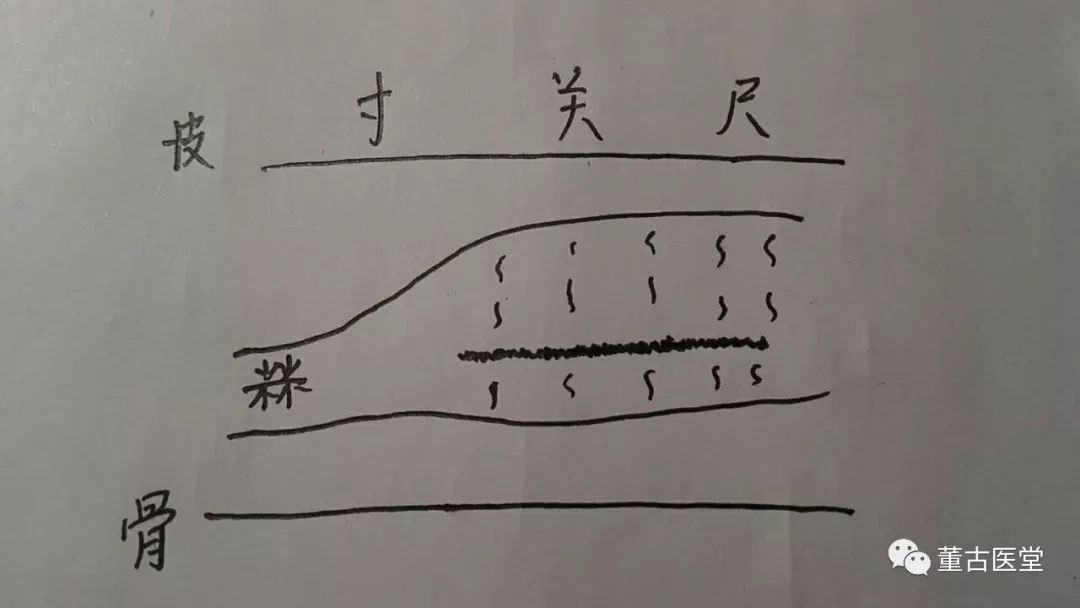

Pulse diagnosis revealed: the Cùn Mài (寸脉) was deep and wiry, while the Guān Mài (关脉) and Shǐ Mài (尺脉) were soft and large, with a fine and rough sensation in the middle section.

Tongue diagnosis showed: a thin, pale tongue with a light color and little moisture on the surface.

The pulse image is as follows:

This is a case of Tàiyáng Bìng (太阳病) with a deficiency pattern transitioning to Tàiyáng Shàoyáng Bìng (太阳少阳病), combined with dampness and water retention.

The prescription is based on the framework of Xiǎo Chái Hú Tāng (小柴胡汤). The formula includes Guī Qí Jiàn Zhōng Tāng (归芪建中汤) with added Líng Guì Zhú Shì Gān Tāng (苓桂术甘汤) and Chái Hú (柴胡), Rén Shēn (人参).

Due to the wiry Cùn Mài, Líng Guì Zhú Shì Gān Tāng is used.

Given the yellow complexion and normal urination, Guī Qí Jiàn Zhōng Tāng is applied. Following the Shāng Hán Lùn (伤寒论): for those with yellow complexion and normal urination, treatment for deficiency patterns is indicated, and Guī Qí Jiàn Zhōng Tāng is the main formula.

Because the pulse is fine and rough, Dāng Guī (当归), Rǔ Xiāng (乳香), and Mò Yào (没药) are included.

The condition is located in the head, originally a Tàiyáng Bìng position. Due to the patient’s significant work stress, there is stagnation in the middle burner, leading to the presence of Shàoyáng Bìng (少阳病).

The prescription is as follows:

Fú Lìng (茯苓) 15g, Cāng Zhú (苍术) 10g, Guì Zhī (桂枝) 10g, Zhì Gān Cǎo (炙甘草) 10g

Qiāng Huó (羌活) 10g, Zé Xiè (泽泻) 20g, Huáng Qí (黄芪) 20g, Dāng Guī 20g

Rǔ Xiāng 5g, Mò Yào 5g, Chái Hú 20g, Rén Shēn 6g

Lóng Gǔ 20g, Mǔ Li 20g, Bái Sháo (白芍) 20g, Dà Zǎo (大枣) 10g

Shēng Jiāng (生姜) 10g, 5 doses.

Why is this considered a prescription based on the framework of Xiǎo Chái Hú Tāng? Because the Líng Guì Zhú Shì Gān Tāng in the formula represents the half of Xiǎo Chái Hú Tāng with Rǔ Xiāng and Mò Yào representing the Huáng Qín (黄芩) aspect of Xiǎo Chái Hú Tāng.

After taking the medicine, the patient reported improvement in hair loss, the bitter taste in her mouth was nearly gone, and her sleep improved.

Personally, I do not treat hair loss frequently. I usually use Jiàn Zhōng Tāng (建中汤) combined with Líng Guì Zhú Shì Gān Tāng, which has shown good results.

Hair loss is fundamentally a Tàiyáng Bìng condition.

If it is purely a Tàiyáng Bìng deficiency pattern, Jiàn Zhōng Tāng is sufficient. If it is a severe deficiency pattern, Guì Zhī Jiā Lóng Gǔ Mǔ Li Tāng (桂枝加龙骨牡蛎汤) should be used.

For Tàiyáng Bìng with water retention, Xiǎo Jiàn Zhōng Tāng (小建中汤) combined with Líng Guì Zhú Shì Gān Tāng is recommended. I believe this is a relatively common pattern.

Tàiyáng Bìng with dampness is also very common. Usually, Zé Xiè is added, and Bái Zhú (白术) is replaced with Cāng Zhú.

Tàiyáng Bìng with dampness transitioning to Tàiyáng Yángmíng Bìng (阳明病) with dampness is also quite common. For mild Yángmíng conditions, it should be treated with Rǔ Xiāng and Mò Yào. For severe Yángmíng conditions, it should be treated for blood dryness and heat accumulation, which is less common, and I have less experience with.

The more combined patterns there are, the more transformations occur, making treatment increasingly difficult.