Pulse diagnosis is one of the four examinations in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), referring to the physician using their hands to perform a form of examination on the patient, either by pressing, touching, or tapping, to obtain information for pattern differentiation. Pulse diagnosis includes two parts: pulse examination and palpation.

1、Pulse Examination

Pulse examination involves pressing the patient’s arteries with the fingers to understand the internal changes of the disease, also known as pulse taking or diagnosing the pulse. The pulse is the vessel of blood, circulating throughout the body, with the qi and blood of the five organs and six bowels flowing through the blood vessels. When the body is stimulated by internal or external factors, it inevitably affects the circulation of qi and blood, leading to changes in the pulse. The physician can assess the condition of the organs, the strength and weakness of qi and blood, the presence of pathogenic factors, and the nature of the disease (exterior/interior, deficiency/excess, cold/heat) by understanding the depth, speed, strength (forceful or weak), rhythm (regular or irregular), shape (size), and smoothness of the pulse.

For example, when the disease is at the surface, it presents as a floating pulse; when the disease is in the organs, it presents as a deep pulse; in cases of yin deficiency, where yang qi is insufficient and blood flow is slow, it presents as a slow pulse; in cases of yang excess, where blood flow is accelerated, it presents as a rapid pulse. Pulse diagnosis is an important basis for TCM pattern differentiation, with rich experience accumulated over a long period. However, there are special cases where the pulse does not match the symptoms, such as a yang pulse appearing in a yin condition or a yin pulse appearing in a yang condition. Therefore, relying solely on pulse diagnosis is very one-sided; it is essential to emphasize the integration of the four examinations to understand the full picture of the disease and make an accurate diagnosis.

Pulse taking location: Generally, the cun kou pulse is taken, which refers to the superficial part of the radial artery at the wrist.

Method of pulse taking: During pulse taking, the patient should be seated or lying supine, with the arm extended at the same level as the heart, palm facing up, and the forearm flat to ensure smooth blood flow.

To take the pulse, use the middle finger to press on the radial artery at the styloid process of the radius to locate the guan (position), then use the index finger to locate the cun (distal position), and finally use the ring finger to locate the chi (proximal position). The three fingers should be arranged in a bow shape at the same level, with the finger pads pressing on the pulse. The spacing of the three fingers should be adjusted according to the patient’s height; if the patient is taller, the fingers can be spaced wider, while if the patient is shorter, the fingers can be spaced closer together. The arrangement of the fingers should be neat; otherwise, it may affect the accuracy of the pulse shape.

In children, the cun kou area is small and cannot accommodate three fingers, so one finger (the thumb) can be used to locate the guan without subdividing into three parts. For children under three years old, the appearance of the fingerprints can replace pulse taking.

During pulse taking, three levels of pressure are used: initially light pressure to feel the pulse at the surface, known as lifting; then moderate pressure to feel the pulse in the muscle, known as searching; and finally heavy pressure to feel the pulse in the tendons and bones, known as pressing. Depending on clinical needs, lifting, searching, and pressing can be repeated in any order, or a single finger can be used to press directly.

The cun, guan, and chi positions each have three levels: floating, middle, and deep, referred to as the three positions and nine levels.

The different positions of the cun kou pulse reflect the functional status of different organs, with the cun, guan, and chi corresponding to specific organs. This is based on the experience of predecessors and has certain reference significance in diagnosing diseases, but in clinical practice, a comprehensive consideration is still necessary.

Precautions for pulse taking:

1. The physician must be fully focused, carefully pressing and repeatedly experiencing the pulse to prevent subjective assumptions and hasty conclusions. The time for each pulse diagnosis should not be less than 50 seconds.2. Pay attention to the influence of internal and external factors on the pulse: for example, children’s pulses are softer and faster than adults’, women’s pulses are generally finer and slightly faster than men’s, and obese individuals have deeper pulses compared to thinner individuals. In summer, pulses are generally larger, while in winter, they are smaller. After intense exercise, the pulse may be rapid, and after drinking alcohol, the pulse may also be rapid. Mental stimulation and certain medications can also cause temporary changes in the pulse.3. Some individuals may have anatomical variations in the radial artery, leading to the pulse not being detectable at the cun kou position but rather at the thumb’s wrist side, known as reversed guan pulse, or slanting towards the back of the hand, known as slanting flying pulse.

Normal pulse:

The pulse of a healthy person is referred to as a normal pulse. Generally, it is neither floating nor deep, neither large nor small, neither strong nor weak, neither fast nor slow, but rather even and gentle, with a regular rhythm, also known as 平脉 (ping mai) or 缓脉 (huan mai). A normal pulse beats four to five times per breath (one inhalation and exhalation), corresponding to 72-80 beats per minute, with consistent rhythm and strength. The pulse can undergo physiological or temporary changes due to internal and external factors, which is also normal. For example, the younger the individual, the faster the pulse; infants may have a pulse rate of 120-140 beats per minute, while children aged five to six may have a pulse rate of 90-110 beats per minute. Young adults typically have a strong pulse, while the elderly may have a weaker pulse. Adult women generally have a finer and slightly faster pulse than adult men, and thinner individuals may have a floating pulse, while obese individuals may have a deeper pulse. Heavy physical labor, intense exercise, long-distance walking, overeating, emotional excitement, and hunger can all lead to a faster and stronger pulse.

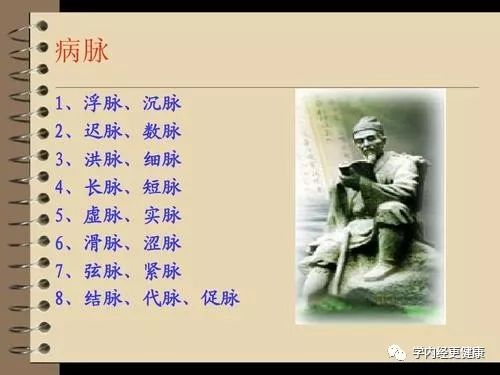

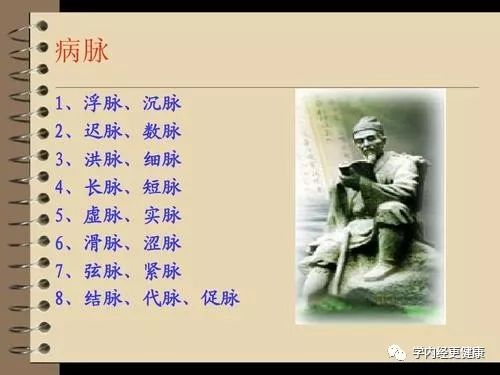

Abnormal pulse and clinical significance:

In the classical texts of Chinese medicine, 28 types of pathological pulses are recorded. However, the classification of pulse types based on pulse position, rate, strength, shape, and smoothness is often mixed. Some pathological pulses are composed of two or more single pulse types. Below are 14 common pulse types and their clinical significance:

(1) Floating Pulse

The pulse is superficial. It can be felt with light pressure, but feels slightly reduced with heavy pressure. This pulse often indicates an exterior syndrome, suggesting the disease is at the surface. A floating tight pulse indicates exterior cold, a floating rapid pulse indicates exterior heat, a floating strong pulse indicates excess, and a floating weak pulse indicates deficiency. It is commonly seen in the early stages of colds, flu, and various infectious diseases. However, in cases of chronic illness or yin deficiency with yang not supporting, a floating weak pulse may also appear.

(2) Deep Pulse (Fùfú Pulse)

The pulse is deep. It is not felt with light pressure, but can be felt with heavy pressure. This pulse indicates an interior syndrome; a deep strong pulse indicates interior excess, a deep weak pulse indicates interior deficiency, a deep slow pulse indicates interior cold, a deep rapid pulse indicates interior heat, and a deep choppy pulse indicates qi stagnation or blood stasis. It is commonly seen in conditions like edema, abdominal pain, chronic illness, and various weakness-related diseases.

Fùfú pulse: This pulse is even deeper than the deep pulse and can only be felt with significant pressure, indicating internal obstruction of pathogenic qi or severe pain or syncope.

(3) Slow Pulse

The pulse rate is low, with fewer than four beats per breath (less than 60 beats per minute), indicating a cold syndrome. A slow strong pulse indicates cold accumulation (yang deficiency with yin excess), while a slow weak pulse indicates 虚寒证 (xu han zheng), commonly seen in conditions like heart qi deficiency.

(4) Rapid Pulse (Fùjī Pulse)

The pulse rate is high, with more than six beats per breath (more than 90 beats per minute), indicating a heat syndrome. A floating rapid pulse indicates exterior heat, a deep rapid pulse indicates interior heat, a surging rapid pulse indicates excess heat, a thin rapid pulse indicates deficiency heat, and a wiry rapid pulse indicates liver fire excess. It is commonly seen in heat-related diseases or hyperthyroidism, and a rapid weak pulse may also be seen in 气虚证 (qi xu zheng).

Jí pulse: This pulse has a rate of seven to eight beats per breath (approximately 120 beats per minute) and often indicates extreme yang excess, with yin qi about to be depleted, or a critical condition.

(5) Slippery Pulse

The pulse feels smooth and flowing, like rolling beads, often indicating excess pathogenic factors, phlegm, or food stagnation. This pulse may also be seen in healthy individuals with abundant qi and blood, and is commonly observed in pregnant women. In pathological conditions, it is often seen in phlegm-dampness, food stagnation, blood stasis, and excess heat, such as various inflammations, indigestion, and menstrual disorders.

(6) Choppy Pulse

The pulse feels rough and stagnant, like scraping bamboo, often indicating deficiency of essence, blood deficiency, qi stagnation, or blood stasis, commonly seen in conditions like anemia, blood loss, postpartum recovery, and blood stasis.

(7) Wiry Pulse

The pulse is straight and long, like pressing a bowstring, with significant tension and elasticity, indicating qi stagnation, liver and gallbladder diseases, and pain syndromes. It is commonly seen in exterior 少阳证 (shao yang zheng), liver diseases, gallbladder diseases, hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and various pain conditions.

(8) Tight Pulse

The pulse feels tense and strong, like a tightly twisted rope, indicating cold syndromes, pain syndromes, and food stagnation. It is seen in conditions like exterior wind-cold and severe pain.

(9) Moderate Pulse

This pulse has a rate of four beats per breath, neither fast nor slow, neither strong nor weak, and feels gentle, indicating a normal pulse with sufficient stomach qi, commonly seen in healthy individuals. In pathological conditions, it may indicate dampness obstructing qi.

(10) Flooding Pulse (Dà mài)

The pulse is large and surging, like turbulent waves, with a wide shape and significant fluctuation, indicating a heat syndrome with excessive yang heat. It is commonly seen in patients with high fever.

Large pulse: This pulse is large but does not exhibit the surging pattern, often indicating disease progression, where a large and strong pulse suggests disease advancement, while a large and weak pulse suggests deficiency.

(11) Thin Pulse (Small Pulse)

The pulse is thin like a thread, narrow, and with small fluctuations, indicating deficiency syndromes (qi deficiency and blood deficiency). It is commonly seen in various deficiency conditions and chronic diseases.

Small pulse is synonymous with thin pulse, indicating the same conditions.

(12) Rapid Pulse

The pulse is rapid and irregular, sometimes stopping, with an unpredictable rhythm, indicating yang excess heat or stagnation of qi, blood, phlegm, or food, commonly seen in conditions of qi stagnation, blood stasis, and various heat syndromes. A thin rapid pulse with weakness often indicates a state of collapse.

(13) Knotted Pulse

The pulse is slow and irregular, sometimes stopping, indicating yin excess cold accumulation or qi and blood stasis, commonly seen in conditions of qi stagnation, blood stasis, phlegm accumulation, and hernia pain. A knotted weak pulse indicates qi and blood deficiency, commonly seen in chronic illness and various heart diseases causing arrhythmia.

(14) Intermittent Pulse

The pulse stops and starts, with a regular rhythm, indicating a weak state of the organ qi, commonly seen in arrhythmias such as 二联律 (dian lian lv) and 三联律 (san lian lv).

Combined pulses and their associated diseases:

The causes of diseases are multifaceted, and the manifestations and changes of diseases are complex. Therefore, the common pulse types often reflect multiple aspects of the disease. Combined pulses, also known as composite pulses, are a comprehensive representation of two or more single pulse types. As long as they are not completely opposite, two or more single pulses can appear simultaneously and form a combined pulse, such as floating tight, floating rapid, deep slow, deep thin rapid, etc. The clinical significance generally reflects the sum of the diseases associated with the individual pulses, such as floating tight pulse indicating exterior cold syndrome; floating rapid pulse indicating exterior heat syndrome; deep slow pulse indicating interior cold syndrome; deep thin rapid pulse indicating interior deficiency heat syndrome, etc.

Pulse Recording:

Using a pulse recorder to depict the pulse wave curve can be divided into wave radiation, main wave, rising branches, falling branches, notches, and heavy waves. Due to differences in the performance of recording instruments and measurement parameters, the results may not be uniform. However, the recorded characteristics of floating, deep, slow, rapid, flooding, wiry, slippery, choppy, thin, large, tight pulses are generally consistent with those obtained through pulse taking. For example, a floating pulse can be clearly recorded without applying pressure, while applying external pressure (equivalent to heavy pressure during pulse taking) may reduce the pulse wave. Conversely, a deep pulse cannot be recorded without external pressure and requires sufficient pressure to depict the wave curve. A flooding pulse shows a particularly high wave amplitude, with the main wave sharply rising and quickly falling, corresponding to the surging pattern during pulse taking. A wiry pulse shows a flat peak after a short duration of the main wave, corresponding to the sensation of pressing a bowstring during pulse taking. Rapid and slow pulses reflect changes in pulse rate, and the recorded results are completely consistent with pulse taking. A slippery pulse rises and falls rapidly, with a significant heavy wave, appearing smooth and flowing like beads. A thin pulse has a low amplitude, with small slopes in both rising and falling phases. A choppy pulse has a slower rise and fall compared to a thin pulse, with small notches visible during the rise and fall, indicating a lack of smoothness during pulse taking.

Principles of Pulse Formation:

Research in this area has accumulated some data. The changes in pulse are based on a broad pathological and physiological foundation, closely related to cardiovascular function and the neurohumoral regulatory system.

The pulse is composed of the rate, rhythm, strength, position, and shape of the pulse, which are related to cardiac output, heart valve function, blood pressure, the quality and quantity of blood in the vessels, and the functional state of peripheral blood vessels.

The formation of a floating pulse may be related to decreased (or normal) cardiac output, peripheral vascular constriction, and increased vascular elastic resistance, which can be seen as reduced voltage on an electrocardiogram.

A slow pulse can be seen on an electrocardiogram as sinus bradycardia, which may be caused by increased vagal excitability, atrioventricular conduction block, or junctional rhythm.

A rapid pulse can be seen on an electrocardiogram as sinus tachycardia, which may be caused by factors such as infection leading to decreased blood pressure, resulting in sinus tachycardia, or increased myocardial excitability and decreased myocardial strength, leading to compensatory increases in heart rate.

A weak pulse is often due to decreased cardiac output, reduced vascular elastic resistance, and lowered blood pressure.

A strong pulse is related to increased cardiac output and vascular elastic resistance, with normal pulse pressure.

A slippery pulse indicates normal or slightly increased cardiac output, normal or decreased vascular elastic resistance, thinner blood, and increased blood flow, resulting in smooth blood flow, which is reflected in the wave-like appearance on the vessels.

A choppy pulse may be related to vagal excitability, decreased heart rate, reduced cardiac output, and peripheral vascular constriction.

A flooding pulse may be related to increased cardiac output, peripheral vascular dilation, high systolic pressure, low diastolic pressure, large pulse pressure, and increased blood flow velocity.

A thin pulse may be related to decreased heart function, reduced cardiac output, peripheral vascular constriction, increased vascular elastic resistance, and small pulse pressure.

A weak pulse may be related to decreased cardiac output and low vascular elastic resistance.

A wiry pulse may be related to poor arterial wall elasticity or arteriosclerosis, vascular smooth muscle contraction, thickening of the vascular wall, and increased vascular resistance during diastole, leading to increased arterial tension and elevated blood pressure. The appearance of a wiry pulse during pain or liver disease may be the result of neurohumoral changes affecting vascular function, with complex formation factors.

A tight pulse may be related to increased cardiac output, peripheral vascular constriction, and increased arterial tension.

A rapid pulse may indicate atrial fibrillation or tachycardia with premature contractions.

A knotted pulse may be seen on an electrocardiogram as various premature contractions, escape beats, pauses, and atrial fibrillation.

An intermittent pulse is seen in premature contractions or second-degree atrioventricular block, leading to 二联律 (dian lian lv) and 三联律 (san lian lv).

Rapid, knotted, and intermittent pulses are all irregular rhythms, primarily resulting from intrinsic cardiac disease, and certain medications such as digitalis toxicity can also cause knotted and intermittent pulses.

2、Palpation

Palpation is a method used by physicians to touch and press on the patient’s skin, limbs, chest, and abdomen to discern their temperature, moisture, softness, hardness, swelling, lumps, and the patient’s response to pressure, such as pain, preference for pressure, or aversion to pressure, to infer the location and nature of the disease.

Skin palpation: To distinguish temperature and moisture, as well as swelling.

The temperature of the skin generally reflects the body’s temperature, but it is important to note that when heat pathogens are internally obstructed, the chest and abdomen may feel hot while the limbs and forehead may not feel as warm, or even feel cool. The moisture and dryness of the skin can reflect whether there is sweating, dryness, or depletion of body fluids. For example, moist skin generally indicates that body fluids are intact, while dry and wrinkled skin indicates fluid depletion, significant qi and yin deficiency, and chronic illness may lead to extremely dry skin that feels prickly to the touch, known as 肌肤甲错 (ji fu jia cuo), indicating insufficient yin blood and internal blood stasis. If the skin sinks and forms a pit when pressed, it indicates edema, while if the skin is swollen and rebounds when pressed, it indicates qi edema or false obesity.

Limbs palpation: Cold limbs indicate a deficiency of yang, while cold extremities indicate 亡阳 (wang yang) or internal heat obstruction. If the body feels hot but the fingertips are cold, it may indicate yang deficiency or a precursor to heat obstruction and convulsions. Warm palms and soles indicate 阴虚发热 (yin xu fa re). Additionally, limb palpation should also check for paralysis or rigidity in the limbs.

Chest palpation: To assess the severity of internal deficiency. The apex beat (the heartbeat felt in the left fourth or fifth intercostal space) is the root of all pulses. When pressed, it should feel soft, moving without tension, neither fast nor slow, indicating that the vital qi is accumulating in the chest, which is a sign of health. If the movement is weak and not prominent, it indicates internal deficiency of vital qi. If the movement is strong and felt through clothing, it indicates leakage of vital qi. If the movement is only temporary and soon returns to normal, it is often seen after fright or heavy drinking. Generally, a fatter person has a weaker apex beat, while a thinner person has a stronger apex beat, which does not indicate pathology.

Pressing below the heart (the area below the sternum) assesses the hardness and tenderness of the area. If it feels hard and painful, it indicates 结胸 (jie xiong), which is a solid condition; if it feels soft and painless, it indicates 痞证 (pi zheng), which is a deficiency condition.

Abdominal palpation: To discern the location of lesions, abdominal pain, and the nature of masses.

Lesions in the epigastric area (upper middle abdomen) indicate stomach issues, while lesions in the flanks (left and right sides of the abdomen) indicate liver and gallbladder issues. Lesions around the navel indicate stomach or intestinal issues, while lesions in the lower abdomen indicate liver, bladder, or kidney issues.

If pressing reduces pain (preference for pressure), it often indicates deficiency pain, while if pressing increases pain (aversion to pressure), it often indicates excess pain or heat pain.

If there is a mass in the abdomen that feels soft and can disperse, it is called a 瘕 (jia) or 聚 (ju), often indicating qi stagnation. If the mass is firm and cannot disperse, it is called a 瘕积 (jia ji), often indicating blood stasis, phlegm, or water accumulation as 实邪 (shi ye).

Pressing on the yu points: Organ lesions can manifest at corresponding surface acupoints. By palpating the meridian yu points, nodules, cord-like structures, painful points, or allergic reaction points can be found, which can serve as auxiliary diagnoses for certain diseases. For example, patients with hepatitis may have tenderness at the 期门 (qi men) and 肝俞穴 (gan yu xue); patients with gallbladder diseases may have tenderness at the 胆俞穴 (dan yu xue); patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers may have tenderness at the 足三里穴 (zu san li xue); and patients with acute appendicitis may have significant tenderness at the 阑尾穴 (lan wei xue) (one inch below 足三里 (zu san li)).

Application: Pulse diagnosis is one of the four examinations in TCM. When using pulse diagnosis, it is essential to integrate the four examinations organically and not neglect any aspect. Although pulse diagnosis and tongue diagnosis are unique methods of TCM diagnosis, they should not be mystified. The integration of the four examinations is necessary to comprehensively grasp the changes in the disease, thus providing the necessary basis for accurate diagnosis and treatment.