Facial Observation in TCM

The various parts of the face correspond to different organs, forming the basis of facial observation in TCM. The combination of color and location further enhances the understanding of the patient’s condition.

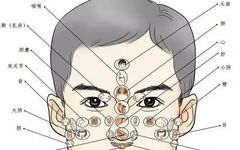

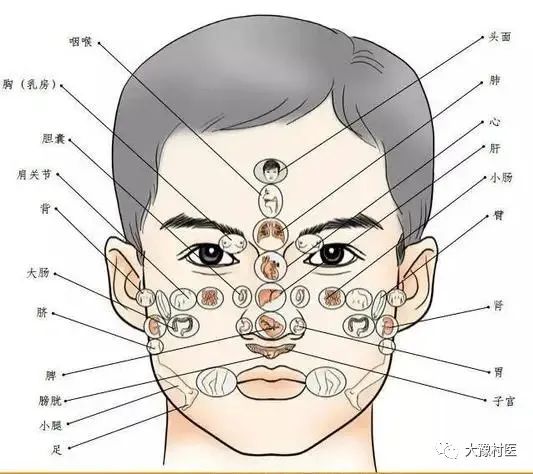

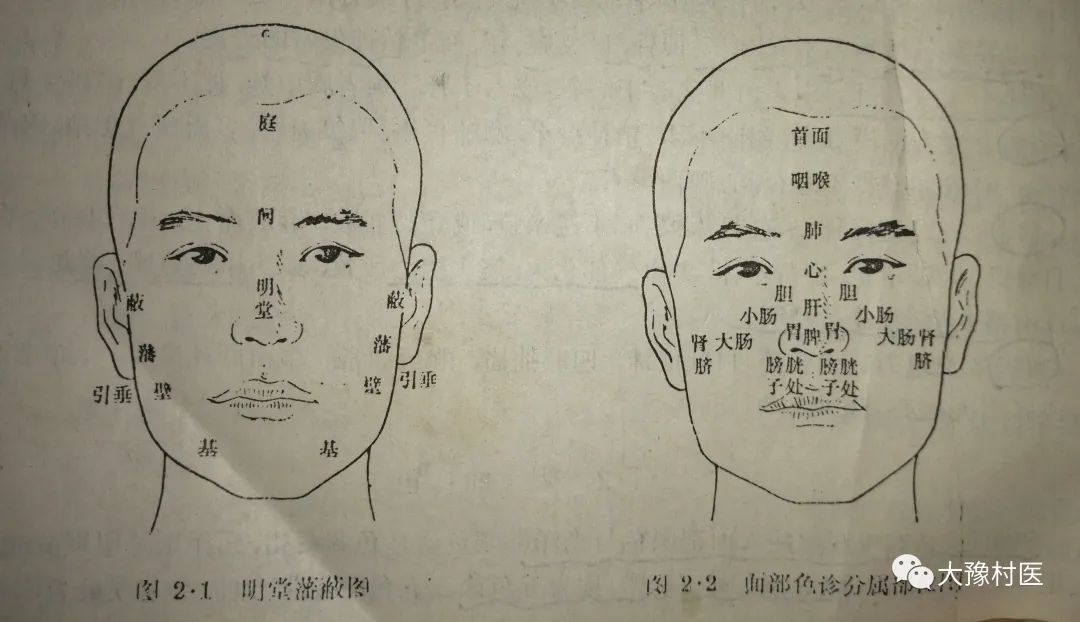

The facial regions corresponding to the organs are classified according to the “Lingshu: Five Colors” as follows: Nose – Ming Tang (Hall of Brightness). Between the eyebrows – Que (Threshold). Forehead – Ting (Yard). Cheeks – Fan (Fence). Ear gates – Bi (Cover) (see Figure 2.1).

According to the aforementioned names and their related positions to the five zang organs, they are: Ting – the head, Que Shang – the throat, Que Zhong (Yintang) – the lung, Que Xia (Xiaji, Mountain Root) – the heart. Below Xiaji (Nianshou) – the liver, the left and right of the liver – the gallbladder, below the liver (Zhun Tou) – the spleen, above Fang (both sides of the spleen) – the stomach, center (below the cheekbones) – the large intestine, adjacent to the large intestine – the kidney, above Ming Tang (tip of the nose) – the small intestine, below Ming Tang – the bladder (see Figure 2.2).

Additionally, the “Suwen: Acupuncture for Heat” divides the five zang organs and their corresponding facial regions as follows: Left cheek – liver, right cheek – lung, forehead – heart, chin – kidney, nose – spleen.

The two methods above serve as primary and clinical references respectively. In summary, the depth of the disease and the clarity of the color vary, and the mechanisms of disease are numerous; therefore, the observation of locations should not be overly mechanical but must be applied flexibly, integrating the four examinations; however, one should not overlook the observation of locations, as the division of regions is the foundation of color diagnosis.

1. Ten Methods of Color Observation

The “Observational Diagnosis Guidelines” states: “In general, for observation, first divide the regions, then observe the qi and color. To understand the subtleties of the five colors, one must know the ten methods.” This indicates that the ten methods have significant meaning in observational diagnosis. Based on the theories of the “Neijing” and personal clinical experience, Wang Hong summarized the ten methods as: Floating and sinking, clear and turbid, subtle and severe, scattered and congested, moist and dry.

Floating is evident on the skin, indicating a superficial disease; sinking is when the color is hidden beneath the skin, indicating an internal disease. Initially floating then sinking indicates the disease has moved from the surface to the interior; initially sinking then floating indicates the disease has moved from the interior to the surface. Clear indicates clarity and comfort, suggesting a yang disease; turbid indicates murkiness and discomfort, suggesting a yin disease. Transitioning from clear to turbid indicates a yang disease turning into a yin disease; transitioning from turbid to clear indicates a yin disease turning into a yang disease. Subtle indicates a light color, suggesting a deficiency of righteous qi; severe indicates a deep color, suggesting an excess of pathogenic qi. Scattered indicates separation, with an open color, suggesting the disease is about to resolve; congested indicates stagnation, with a closed color, suggesting the disease has been lingering. Initially scattered then congested indicates the disease is close to resolution but gradually accumulating; initially congested then scattered indicates the disease has been lingering but is about to resolve. Moist indicates a moist and lustrous color, suggesting life; dry indicates a withered and dull color, suggesting death. Initially dry then gradually moist indicates a recovery of spirit; initially moist then dry indicates a decline in blood and qi. In summary, the ten methods can be used to distinguish between superficial and deep, yin and yang, deficiency and excess, duration and proximity, success and failure. The “Observational Diagnosis Guidelines” states: “The ten methods discern the qi of color, while the five colors discern the color of qi.” This illustrates the significance of the ten methods and their relationship with color observation.

2. Normal Color and Disease Color

(1) Normal Color: Normal color refers to the facial complexion of a person in a normal physiological state, indicating the fullness of spirit, qi, blood, and body fluids, as well as the normal function of the zang organs. Due to the internal essence, the complexion radiates outward, so a normal person’s facial color should be bright and moist. As stated in the “Observational Diagnosis Guidelines”: “Brightness indicates the manifestation of spirit; moisture indicates the fullness of essence and blood.”

In our country, a normal person’s facial color should be a subtle red-yellow, bright and reserved. This indicates the presence of stomach qi and spirit. However, due to individual constitution differences, some may appear more red, black, or white; due to physiological activity changes, some may appear blue, white, or red, etc. These are all normal phenomena, so regardless of color, as long as there is spirit and stomach qi, it is considered normal color. The so-called spirit refers to brightness and moisture; the so-called stomach qi refers to a subtle yellow, reserved and not exposed.

Due to changes in time, climate, and environment, normal color can also be divided into main color and guest color.

a. Main Color: Each person’s facial color is not uniform among the population, belonging to individual characteristics. The facial color and skin tone that remain unchanged throughout life are considered the main color. For example, due to heredity, region, or working conditions, some individuals may have a white, black, red, yellow, or blue complexion, and as long as it remains unchanged throughout life, it becomes the main color. As stated in the “Yizong Jinjian: Four Diagnostic Methods Key Points”: “The colors of the five zang organs manifest according to the five shapes of individuals and do not change for a hundred years, hence they are the main colors.” According to the theory of the five elements, a person with a wood constitution appears blue, earth constitution appears yellow, fire constitution appears red, metal constitution appears white, and water constitution appears black, which is due to inherent characteristics.

b. Guest Color: Humans correspond with nature, and due to changes in living conditions, a person’s facial color and skin tone also change accordingly, which is called guest color. For example, with the changes of the four seasons, day and night, and weather conditions, the facial color also changes accordingly. According to the theory of the “Neijing”, spring qi resides in the meridians, summer qi in the collaterals, late summer qi in the muscles, autumn qi in the skin, and winter qi in the bone marrow. With the internal and external changes of qi, the color also has floating and sinking variations. According to the theory of the five elements, spring corresponds to a slight blue, summer to a slight red, late summer to yellow, autumn to a slight white, and winter to a slight black, with all seasons being yellow. These changes are not very obvious and require careful observation to discover and comprehend. During the day, qi flows in yang, and the color should be bright and reflective; at night, qi flows in yin, and the color should be bright and moist. In sunny weather, qi is warm, and warmth leads to moisture, resulting in yellow and red; in cloudy weather, qi is cold, and cold leads to blood stagnation, resulting in blue and black. These all belong to complexion, as stated in the “Yizong Jinjian: Four Diagnostic Methods Key Points”: “The colors of the four seasons change with the seasons, hence they are guest colors.”

Both main color and guest color are normal physiological phenomena. Additionally, factors such as drinking alcohol, running, emotional states, or occupational exposure to sunlight, or prolonged sun exposure, as well as geographical and ethnic factors can also cause changes, which are not considered disease colors and must be noted during diagnosis.

(2) Disease Color: Disease color refers to the facial complexion of a person in a state of illness, and can be considered that all abnormal colors other than the aforementioned normal colors belong to disease color. The appearance of disease color, regardless of color, whether dark and withered, or bright and exposed, or even bright and reserved but not appropriate for the time and place, or a single color appearing, all constitute disease color. Ancient physicians, based on extensive clinical experience, not only discovered that the five colors correspond to the pathological changes of the respective zang organs, but also reflect certain pathogenic nature. Due to the varying severity of the disease, the luster also changes, thus disease color can be classified into good and bad.

Five Colors of Good and Bad: Generally, bright and moist five colors are considered good colors, indicating that although there is illness, the essence and qi of the zang organs have not declined, and the stomach qi still nourishes the face, referred to as “qi arriving”, often indicating a good prognosis. Conversely, dull and withered five colors are considered bad colors, indicating that the zang organs may be damaged, and the stomach qi has been exhausted, unable to nourish and moisten, referred to as “qi not arriving”, often indicating a poor prognosis. The “Observational Diagnosis Guidelines” considers color to be based on moisture, which implies that it is based on stomach qi, and color is valued for its spirit, also referring to the moisture of color.

The “Suwen: Generation of the Five Zang” specifically describes the model of good and bad five colors: Blue like emerald feathers, red like a rooster’s comb, yellow like a crab’s belly, white like pig fat, black like crow feathers are all good colors indicating life; Blue like grass, red like blood, yellow like bitter orange, white like withered bones, black like charcoal are all bad colors indicating death. This vividly describes the brightness of good colors and the darkness of bad colors, which will help in understanding the distinction between good and bad colors.

Clinically, one can also observe dynamic changes, where a transition from good to bad color indicates a worsening condition, while a transition from bad to good color indicates a turning point in the disease, possibly leading to recovery. Furthermore, the intermingling of disease colors can indicate the prognosis of the disease. If the disease and color correspond, it is a correct disease and correct color, if the colors do not correspond, it is called intermingling of disease color. In intermingling, there are also relationships of mutual generation and mutual restraint, where mutual generation is considered smooth, and mutual restraint is considered adverse. For example, if liver disease presents with blue color, it is a correct disease and correct color, indicating a normal development of the disease. If black (water generates wood) or red (wood generates fire) appears, it is a color of mutual generation that is considered smooth; if yellow (wood restrains earth) or white (metal restrains wood) appears, it is a color of mutual restraint that is considered adverse. In smooth conditions, color generating disease is considered auspicious, while disease generating color is considered slightly adverse; in adverse conditions, color restraining disease is considered ominous, while disease restraining color is considered auspicious. Other organs can be inferred similarly. However, in clinical application, one should not be overly mechanical, but should integrate the four examinations, apply them flexibly, and make comprehensive judgments to achieve accurate diagnosis. As stated in the “Observational Diagnosis Guidelines”: “If the color is dry and not moist, even if they are mutually generating, it is difficult to treat; if the color is not dry, even if they are mutually restraining, it can still be treated.”

Five Colors and Their Associated Diseases

The five colors correspond to diseases, and when combined with regions and the ten methods, it becomes quite complex; however, if one grasps the key points, one can apply them flexibly. The following outlines the diseases associated with the five colors.

Blue: Corresponds to cold syndromes, pain syndromes, blood stasis, and convulsions.

Cold stagnation leads to qi stagnation and blood stasis, causing the complexion to appear blue, even cyanotic; obstruction of the meridians leads to pain; blood not nourishing the tendons can lead to internal liver wind causing convulsions. When internal cold is excessive, the meridians become tense and qi and blood stagnate, leading to severe abdominal pain, which can present as a pale, light blue, or dark blue complexion. Heart yang deficiency, poor blood circulation, and blood stasis can lead to stabbing pain in the chest, presenting as a gray-blue complexion and cyanotic lips. In children, convulsions or the tendency to convulse often manifest as blue color around the eyebrows, nose, and lips. Women with a blue complexion often have a strong liver and weak spleen, with poor appetite and frequent anger, or menstrual irregularities. A blue complexion with red cheeks indicates a Shaoyang disease with alternating chills and fever; a blue complexion with red ears often indicates liver fire; a blue-red and dull complexion often indicates stagnant fire. A blue complexion in spleen disease is often difficult to treat.

Red: Corresponds to heat syndromes; bright red indicates excess heat, while slight redness indicates deficiency heat.

When qi and blood are heated, they circulate, and with excessive heat, the blood vessels become engorged, leading to a red complexion. A full and bright red complexion often indicates an exterior heat invasion or excess heat in the organs; if both cheeks are flushed and tender, it indicates a deficiency heat syndrome due to yin deficiency. In patients with chronic or severe illness, a pale complexion with flushed cheeks resembling makeup, tender red with white, and fluctuating indicates a critical condition of true cold and false heat. Lung disease presenting with red color is often difficult to treat.

Yellow: Corresponds to deficiency syndromes and dampness.

Yellow is a sign of spleen deficiency and damp accumulation. When the spleen fails to transport effectively, dampness accumulates internally, and qi and blood are insufficient, leading to a yellow complexion. A pale yellow, withered complexion is referred to as “withered yellow”, commonly seen in cases of spleen and stomach qi deficiency and insufficient qi and blood. A yellow complexion that is floating is referred to as “yellow and plump”, often caused by spleen qi deficiency and dampness obstructing internally.

When the entire face and body are yellow, it is referred to as “jaundice”; yellow and bright like orange indicates “yang jaundice”, caused by damp-heat accumulation; yellow and dark like smoke indicates “yin jaundice”, caused by cold damp obstruction. Yellow and emaciated indicates stomach disease with deficiency heat; yellow and pale indicates stomach disease with deficiency cold.Abdominal distension with a yellow complexion and emaciation indicates deficiency distension; if the complexion is pale yellow, with abdominal muscles distended, or if the complexion is withered yellow with red spots resembling crab claws, it often indicates spleen deficiency, liver stagnation, blood stasis, and water retention. In children, a yellow and swollen face or alternating yellow and white with distended abdomen and visible veins indicates malnutrition. A bright and moist Yintang and Zhun Tou indicates recovery of stomach qi and impending recovery.

White: Corresponds to deficiency syndromes, cold syndromes, blood loss, and qi deficiency.

White indicates a lack of nourishment in qi and blood. When yang qi is deficient, qi and blood circulation is sluggish, or when qi is consumed and blood is lost, qi and blood are insufficient, or cold stagnation leads to blood stasis, causing the complexion to appear white. A pale, floating white, or ashen complexion often indicates yang deficiency. Sudden pallor accompanied by cold sweat indicates a sudden loss of yang qi. A pale or ashen complexion often indicates qi deficiency; a white complexion without luster, or yellowish-white like chicken skin indicates blood deficiency or blood loss. Severe abdominal pain or shivering due to internal cold can also present with a pale complexion, while lung and stomach deficiency cold can also present with a pale complexion. A white complexion in liver disease is often difficult to treat.

Black: Corresponds to kidney deficiency, cold syndromes, pain syndromes, water retention, and blood stasis.

Black indicates a color of yin, cold, and excess water. Due to kidney yang deficiency, water retention is not transformed, leading to internal cold accumulation, and blood loses warmth and nourishment, causing the complexion to appear dark. Black on the cheeks and face indicates kidney disease. A dry and scorched black complexion often indicates long-term depletion of kidney essence, with deficiency fire scorching yin. A light and dull black complexion indicates kidney disease with cold water; regardless of the duration of the disease, a dark black complexion indicates a lack of yang qi. Dark circles around the eyes often indicate kidney deficiency or water retention, or cold dampness descending causing discharge issues. A black complexion with numbness in the limbs, difficulty bending or straightening, indicates kidney wind and bone pain. A dark black complexion with rough skin indicates blood stasis. A black forehead in heart disease indicates an adverse condition, while a dark black mouth often indicates kidney failure.

Color, Pulse, and Symptoms Combined

Color, pulse, and symptoms are all reflections of disease. In general diseases, color, pulse, and symptoms often appear correspondingly. For example, in liver disease, a blue color with a wiry pulse, chest and flank pain, bitter mouth, and dizziness indicate a correspondence of color, pulse, and symptoms. Sometimes the appearance of color, pulse, and symptoms may not correspond, requiring specific analysis to understand the overall picture of the disease and recognize its essence to guide treatment correctly. For example, if a patient has a fever and a flushed complexion, it presents as a heat syndrome. If one does not take the pulse and uses cold and purging herbs, it can easily lead to errors. A rapid and strong pulse indicates an excess heat syndrome, which is still somewhat appropriate; however, if the pulse is deep, thin, and weak, or floating and empty, it indicates true cold with false heat, and misusing cold and purging herbs can be dangerous. In summary, during the diagnostic process, one must observe comprehensively, as color, pulse, and symptoms cannot be viewed in isolation; thus, the combination of color, pulse, and symptoms is an important principle of diagnosis.

Editor: Yang Wenjie, Physician Email: [email protected]