Huang Qin (Scutellaria baicalensis), Huang Lian (Coptis chinensis), and Huang Bai (Phellodendron amurense) are collectively known as “San Huang”. They all possess the ability to clear heat and dry dampness. The “San Huang” herbs are cold in nature and clear heat, with a bitter taste that helps to dry dampness and has the function of draining fire and detoxifying. Each of the “San Huang” herbs has its own focus: Huang Qin is generally believed to clear lung fire from the upper jiao, Huang Lian drains heart fire and clears dampness from the middle jiao, and Huang Bai drains fire from the lower jiao and clears damp heat.

Huang Lian

Huang Lian, as a traditional Chinese medicinal material, has a long history of medicinal use in China. Historically, the origin of Huang Lian has been relatively stable, and it is now commonly divided into three types: Wei Lian, Ya Lian, and Yun Lian; there are also varieties such as short calyx Huang Lian, five-leaf Huang Lian, and five-split Huang Lian. The dried rhizome is used in medicine, and its main components include: berberine (berberine), coptisine, palmatine, and coptisine.

Regarding its origin, the “Bie Lu” first recorded Huang Lian as “growing in Wuyang Chuan Valley and Shu County, Taishan”, indicating that Huang Lian has been produced in Sichuan since ancient times. However, many ancient texts later recorded that Huang Lian was also produced in Lizhou, Xuanzhou, and other places. Although there are many producing areas for Huang Lian, the highest quality is mostly from Sichuan. Currently, the main production areas of Huang Lian are generally Sichuan, Hubei, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, mostly cultivated artificially.

Huang Lian has many aliases, but later generations have continued to use the name Huang Lian from the “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic” as the standard name. Huang Lian was first recorded in the “Mu Jing” as a superior product, stating: “Huang Lian, bitter and cold in taste, is used for heat in the eyes, tears from injury, brightening the eyes, and for intestinal pain and diarrhea; for women with swelling and pain in the lower abdomen, long-term use makes one forgetful.” The “Bie Lu” adds: “Slightly cold, non-toxic, governs the cold and heat of the five organs, long-term use can stop diarrhea and blood, relieve thirst, eliminate water, benefit bones, regulate the stomach and intestines, benefit the gallbladder, and treat mouth sores.” Huang Lian is a strong bitter and cold herb, specializing in clearing heat and drying dampness, and detoxifying. The symptoms described in the “Ben Jing” and “Bie Lu” are all caused by evil fire or damp heat, which is why Huang Lian is used to govern them. Huang Lian was already a commonly used medicine during the Han Dynasty, with 15 formulas containing Huang Lian recorded in classical prescriptions, of which one formula has been lost, and 14 formulas remain, all for its heat-clearing properties.

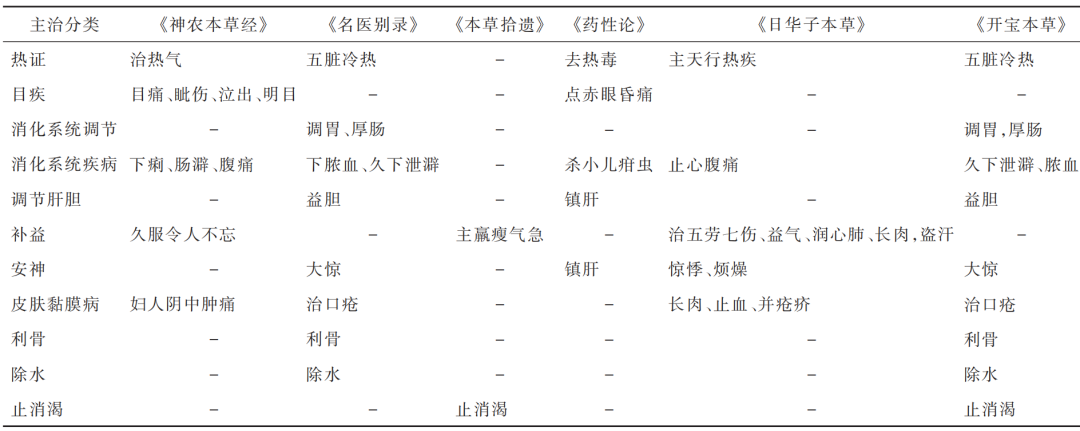

Statistics show that the functions of Huang Lian in herbal texts before the Song Dynasty include several aspects: heat syndrome, eye diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, liver and gallbladder diseases, deficiency syndromes, mental disorders, skin and mucous membrane diseases, and bone diseases.

Throughout history, herbal texts have provided detailed records of Huang Lian’s properties, flavors, meridian entry, and therapeutic effects, confirming the characteristics of Huang Lian as bitter and cold before the Song Dynasty.

In terms of therapeutic effects, ancient herbal texts from the Qin and Han Dynasties and the Southern and Northern Dynasties mainly reflect: “Clearing stomach and liver fire, drying dampness, and detoxifying”. Additionally, the “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic” mentions that Huang Lian can treat swelling and pain in women’s lower abdomen, and the “Bie Lu” first mentions Huang Lian’s effect of stopping thirst. By the Tang and Song Dynasties, the effects of Huang Lian gradually expanded, for example, the “Yao Xing Lun” mentions “killing children’s intestinal worms”, and the “Ben Cao Shi Yi” mentions “governing emaciation and shortness of breath”, while the “Ri Hua Zi Ben Cao” mentions “stopping abdominal pain and anxiety”.

After the Jin and Yuan Dynasties, herbal texts further recognized Huang Lian’s therapeutic effects and provided more comprehensive records of its meridian entry.

After the Jin Dynasty, physicians mainly discussed Huang Lian’s function of lowering excess fire, and they often explained the aforementioned therapeutic effects from the perspective of clearing heat, draining fire, and drying dampness. However, the explanations for the functions with nourishing properties, such as “benefiting bones”, “promoting flesh”, “benefiting qi”, “regulating the stomach”, and “thickening the intestines”, which were mentioned before the Song Dynasty, still lacked effective explanations. Li Dongyuan explained Huang Lian’s role in eliminating spleen and stomach damp heat, and Miao Xiyong further developed this, proposing that “when the disease is gone, the stomach and intestines will naturally thicken”, believing that Huang Lian treats “heat diarrhea”, “intestinal dysentery”, and “blood in the stool” by eliminating spleen and stomach damp heat. Huang Lian’s ability to drain heart fire and spleen and stomach fire has been widely recognized by physicians throughout history.

By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, many ancient herbal texts provided deeper and more comprehensive explanations of each therapeutic effect of Huang Lian based on the work of predecessors. For example, regarding Huang Lian’s ability to clear heat and dry dampness, the Qing Dynasty’s “Ben Cao Zheng Yi” provided a detailed explanation: “Huang Lian is extremely bitter and cold, bitter and drying dampness, cold overcoming heat, able to drain all excess damp heat… clearing wind fire from eye diseases above, balancing liver and stomach for vomiting in the middle, and relieving abdominal pain below, all are effects of drying dampness and clearing heat.”

In summary, the descriptions of Huang Lian’s therapeutic effects in herbal medical texts mainly include draining heart fire, cooling blood and calming the liver, clearing heat and drying dampness, stabilizing anxiety, stopping dysentery, relieving thirst, detoxifying and killing parasites, treating children’s intestinal accumulation, mouth sores, toothaches, and heat vomiting and diarrhea. Many physicians believe that Huang Lian can only be used for excess heat syndromes; if used for deficiency heat, it may instead increase deficiency yang, leading to a collapse of yang.

Huang Lian’s Medicinal Properties

Huang Lian is cold in nature, indicating a deficiency of yang qi, and its cold nature excels at clearing and descending internal heat, making it suitable for internal heat syndromes.

Huang Lian has a bitter taste, and “sour and bitter promote descent as yin”; the bitter taste primarily promotes descent. Huang Lian is very bitter and belongs to the category of thick-tasting yin herbs, and its bitterness and thickness give it the power to descend.

Huang Lian has a firm texture, and the medicinal part is the root, which has a downward force that enhances its bitter cold ability to clear heat. Additionally, since the medicinal part is the root, it excels at entering the middle jiao and lower jiao, thus the bitter cold Huang Lian is adept at clearing heat evil from the gastrointestinal tract.

Huang Qin

Huang Qin is first recorded in the “Ben Jing” as: “Huang Qin, bitter and neutral in taste, governs various heat, jaundice, intestinal dysentery, diarrhea, expelling water, stopping blood, and treating evil sores and ulcers.” The “Bie Lu” adds: “Greatly cold, non-toxic, treats phlegm heat, heat in the stomach, cramping pain in the lower abdomen, promotes digestion, benefits the small intestine, treats women’s blood stagnation, and stops blood in urine; for children with abdominal pain.” Tao Hongjing states: “Treats running piglet syndrome and heat pain below the navel.” The “Dian Nan Ben Cao” states: “It ascends to drain lung fire and descends to drain bladder fire, treating men’s five types of painful urination, women’s excessive bleeding, regulating menstruation and clearing heat, calming fetal heat, and eliminating six meridian excess heat.” The symptoms described in the “Ben Jing” and subsequent herbal texts are all due to heat evil or damp heat. Huang Qin’s cold nature can clear heat, and its bitterness can dry dampness. Huang Qin is a commonly used herb by Zhang Zhongjing, with 26 classical prescriptions containing Huang Qin. It is primarily used for its heat-clearing, detoxifying, and cooling blood properties. Tao Hongjing states: “The garden variety is called Zi Qin, which is superior; the broken one is called Su Qin.” Zi tea refers to the current variety of Huang Qin, while Su Qin refers to the current dried Huang Qin. Zi Qin is heavy and descends well, good at clearing large intestine fire, while Su Qin is light and ascends well, good at clearing lung fire. Nowadays, the distinction is often not made, and they are generally referred to as Huang Qin. Huang Qin is bitter and cold, and those with weak spleen and stomach should use it cautiously; if necessary, it should be taken with Dang Shen (Codonopsis pilosula) to avoid excessive stimulation of the gastrointestinal tract.Historical Records of Huang Qin

“Ben Cao Tu Jing”: “Zhang Zhongjing treats cold damage with fullness below the heart using the Xie Xin Decoction, which uses Huang Qin in all four formulas because it governs various heat and benefits the small intestine. If there is continuous diarrhea in solar disease, with wheezing and sweating, there are also formulas like Ge Gen Qin Lian Decoction, and it is often used in pregnancy and calming the fetus powder.”

“Yao Lei Fa Xiang”: “Treats damp heat in the lungs, alleviates upper heat, red and swollen eyes, and excessive flesh accumulation. It drains lung fire evil, counteracting the cold water deficiency in the bladder, thus nourishing its source.”

“Yao Xing Fu”: “Bitter, neutral, cold in nature, non-toxic. It can ascend and descend, being yin. Its uses are fourfold: the dry and floating type drains lung fire and eliminates phlegm; the fine and firm type drains large intestine fire and nourishes yin to counter yang; the dry and floating type eliminates wind dampness while retaining heat on the skin surface; the fine and firm type nourishes the source and reduces heat in the bladder.”

“Tang Ye Ben Cao”: “Cold in nature, slightly bitter. Bitter and sweet, slightly cold, thin in taste but thick in qi, yin with a hint of yang, greatly cold, non-toxic. It enters the Taiyin meridian.”

“Ben Cao Gang Mu”: “Jie Gu Zhang states that Huang Qin drains lung fire and treats spleen dampness. Dongyuan Li states that Pian Qin treats lung fire, while Tiao Qin treats large intestine fire. Danxi Zhu states that Huang Qin treats upper and middle jiao fire. Zhang Zhongjing treats Shaoyang syndrome with Xiao Chai Hu Decoction, and in cases of solar and shaoyang combined disease with diarrhea, Huang Qin Decoction is also used. Cheng Wujin states that Huang Qin is bitter and enters the heart, draining heat from the fullness. Huang Qin uniquely enters the hand shaoyin and yangming, as well as the hand and foot taiyin and shaoyang meridians.”

“Huang Qin is cold in nature, bitter in taste, yellow with a hint of green, and its bitterness enters the heart, overcoming heat, draining heart fire, and treating spleen damp heat. This prevents metal from being harmed and prevents stomach fire from flowing into the lungs, thus saving the lungs. Those with lung deficiency should avoid it, as bitter cold can harm the spleen and stomach, damaging its mother. In Shaoyang syndrome, with alternating cold and heat, fullness in the chest and ribs, lack of desire to eat, irritability, nausea, or thirst, or fullness in the abdomen, Huang Qin is also a primary herb for Shaoyang syndrome. Cheng Wujin’s annotations state that the bitterness of Chai Hu and Huang Qin can release the heat of the binding evil. The bitterness of Shao Yao and Huang Qin can stabilize the qi of the stomach and intestines, but the subtleties of treating fire are often overlooked. Yang Shiying’s “Zhi Zhi Fang” states that Chai Hu can reduce heat, but not as effectively as Huang Qin. This is because it is not understood that Chai Hu’s heat reduction is due to its bitterness, which releases and disperses heat, while Huang Qin’s heat reduction is due to its cold nature overcoming heat, thus fundamentally reducing fire. Zhang Zhongjing also states that for abdominal pain in Shaoyang syndrome, Huang Qin should be removed and Shao Yao added. For palpitations and difficulty urinating, Huang Qin should be removed and Fu Ling added. This seems inconsistent with the “Bie Lu” which treats lower abdominal cramping and benefits the small intestine. Cheng’s statement that Huang Qin is cold and can strengthen the kidneys is also not entirely accurate. At this point, one should consider the reverse of the intention and differentiate based on pulse and symptoms. If abdominal pain is due to drinking cold and being chilled, and if the pulse is not rapid, it indicates that there is no heat in the interior, thus Huang Qin should not be used. However, if there is heat-induced abdominal pain, lung heat, and difficulty urinating, can Huang Qin be used? Therefore, those who study should first seek the principles and not just cling to the text. In the past, someone who frequently drank alcohol developed abdominal cramping pain that was bearable, with urination resembling a drip, and no other medicines were effective. They happened to use a decoction of Huang Qin, Mu Tong, and Gan Cao, which resolved the issue. Wang Haizang mentioned someone who, due to deficiency, took too much Fu Zi and developed constipation, and after taking Huang Qin, they recovered. These are all cases of heat-induced pain, so can learners be bound by this? When I was twenty, I suffered from a lingering cough due to a cold, and after breaking my dietary restrictions, I developed bone steaming heat, with my skin feeling like it was on fire, and I was spitting up phlegm daily, thinking I would surely die. My late father happened to think of treating lung heat like fire with irritability and increased daytime symptoms, indicating heat in the qi level. A single Huang Qin decoction was prescribed to drain the lung channel’s qi heat. The next day, my fever subsided, and my phlegm and cough were resolved. The efficacy of the medicine was like a drum responding to a beat, such is the wonder of medicine.

“Jing Yue Quan Shu”: “Bitter in taste, cold in nature, and lighter in qi than taste, it can ascend and descend, being yin with a hint of yang. The dried type is good for entering the lungs, while the solid type is good for entering the large intestine. If one wants it to ascend, it should be stir-fried with wine; if one wants it to descend, it should be used raw. The dried type clears fire from the upper jiao, eliminates phlegm, benefits qi, stabilizes cough, stops bleeding, reduces alternating cold and heat, wind heat, and damp heat headaches, resolves epidemics, clears the throat, and treats lung abscesses and breast abscesses; it especially eliminates heat from the skin surface, thus treating rashes, mouse fistula, and red eyes. The solid type cools heat from the lower jiao, thus treating rashes, mouse fistula, and red eyes. The solid type cools heat from the lower jiao, effectively eliminating dysentery, heat accumulation in the bladder, and blood in the stool. If the fetus is restless due to excessive heat, it should be combined with Sha Ren and Bai Zhu; if abdominal pain is due to heat stagnation, Huang Lian and Hou Po can be added. If the large intestine has no fire and is slippery, it should be used with caution.”

“Zhong Yi Zhong Can Xi Lu”: “Bitter in taste, cool in nature. It is best at clearing heat from the lung channel’s qi level, descending from the spleen to the three jiao, reaching the bladder to facilitate urination. It also effectively enters the spleen and stomach to clear heat, descending to the intestines to treat diarrhea with pus and blood. It also effectively enters the liver and gallbladder to clear heat, treating alternating cold and heat in Shaoyang. It can also regulate qi; regardless of which organ is affected, if there is qi stagnation causing heat, it can clear it. It also effectively clears heat from the body, eliminating heat hidden in the meridians and scattered in the skin. It is suitable for treating lung diseases, liver and gallbladder diseases, and skin diseases; for lung diseases, use the dried Huang Qin; for gastrointestinal diseases, use the solid Huang Qin. In essence, they are all Huang Qin, and their functions are not significantly different.”

Huang Bai

Huang Bai is the bark of the deciduous tree Phellodendron amurense and Huangpi, and it is named for its use of the bark. Its main component is berberine.

Huang Bai, referred to as “Nihong” in the “Ben Jing”, is recorded as a superior product, stating: “Nihong, bitter and cold in taste, governs heat accumulation in the five organs and stomach, jaundice, intestinal hemorrhoids; stops diarrhea, and treats women’s excessive bleeding and yin and yang ulcers.” The “Bie Lu” states: “It governs fright in the skin, heat in the skin, red and painful eyes, and mouth sores.”

Huang Bai’s bitterness can dry dampness, and its cold nature can clear heat, with functions of clearing heat, drying dampness, draining fire, and detoxifying, making it suitable for damp heat accumulation or toxic heat conditions. In later generations, it was also used for conditions of yin deficiency with excessive fire. Zhang Zhongjing mainly used it for jaundice and diarrhea.

Huang Bai’s alias is “Tan Huan”, and it is said to grow in the valleys of Hanzhong Mountain. The Southern Dynasty’s “Bie Lu” and “Ben Cao Jing Ji Zhu” state that “the root is called Tan Huan.” From Tao’s annotations on its aliases, it seems that the Huang Bai used during the “Ben Jing” period was likely the root.

In the “Ben Cao Jing Ji Zhu”, it is recorded: “The Huang Bai from Shaoling is light and thin with a deep color, while that from Dongshan is thick and heavy with a light color. Its root is used in Daoist medicine as a wood fungus, which modern people do not know how to consume. There is also a small tree resembling a pomegranate, with yellow and bitter bark, which is called Zi Bai and also treats mouth sores. Another small tree has many thorns, and its bark is also yellow, which also treats mouth sores.” The descriptions of “its bark is yellow and bitter” and “its bark is also yellow” indicate that both can be used medicinally, suggesting that the medicinal parts have changed over time.

Miao Xiyong’s “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic Commentary”:

“Its taste is bitter, its qi is cold, and its nature is non-toxic, thus it governs heat accumulation in the five organs and stomach. When yin is insufficient, heat begins to accumulate in the stomach and intestines. Jaundice is caused by damp heat, but it must occur in those with true yin deficiency. Diarrhea and hemorrhoids are also caused by damp heat injuring the blood. Diarrhea is due to stagnation, which is also a disease of damp heat invading the stomach and intestines. Women’s excessive bleeding and yin ulcers are all caused by damp heat invading the yin and flowing downwards.”

“Skin heat, red eruptions, red and painful eyes, and mouth sores are all diseases caused by yin deficiency and blood heat. Therefore, it is necessary to supplement the deficiency of yin. When there is deficiency, it should be supplemented, and thus yin can clear heat and dry dampness, and all symptoms will be eliminated. It is a key medicine for the hand shaoyin kidney channel, specifically treating internal heat caused by yin deficiency, with remarkable efficacy that cannot be compared to ordinary medicines.”

Many preparations of Huang Bai are recorded in ancient herbal texts. The Southern and Northern Dynasties’ “Lei Gong Pao Zhi Lun” first recorded the honey preparation method, while the Tang Dynasty’s “Yin Hai Jing Wei” first recorded the wine method, calling it “Jiu Bai”. The Song Dynasty’s “Bian Que Xin Shu” first recorded the salt preparation method, interpreting it as: “Salt water stir-fried, making it salty to enter the kidneys, governing the descent of yin fire to rescue kidney water.” Additionally, there are also methods of stir-frying it to charcoal for use.

Raw Huang Bai is bitter and cold, with strong heat-clearing and damp-drying abilities, thus it is often used for damp heat jaundice, diarrhea, and heat dysuria;

Wine Huang Bai ascends the medicine, clearing blood heat and dampness, thus it is often used for red eyes, sore throat, and tongue sores.

Salt Huang Bai moderates its bitter and drying nature, enhancing its ability to nourish kidney yin and drain excess fire, thus it is often used for yin deficiency heat, bone steaming heat, and night sweats.

The Qing Dynasty’s “Ben Cao Cong Xin” summarized: “Raw use drains excess fire, stir-fried black stops bleeding, wine preparation treats upper conditions, honey preparation treats middle conditions, and salt preparation treats lower conditions.”

The 2015 edition of the “Pharmacopoeia” includes raw Huang Bai, salt Huang Bai, and Huang Bai charcoal.

Distinctions

In herbal texts before the Song Dynasty, Huang Qin mainly had the following effects: clearing various heat, expelling pus, regulating the stomach and gallbladder, eliminating women’s blood stagnation, treating dysuria, breaking qi stagnation, expelling water, and alleviating joint discomfort. Huang Qin is particularly effective for alternating cold and heat, and among the “San Huang”, it excels at regulating qi stagnation. Therefore, in Shaoyang syndrome, Chai Hu and Huang Qin are often used together, typically in an 8:3 ratio corresponding to the numbers of the liver and gallbladder in the He Tu and Luo Shu. Huang Qin’s medicinal properties tend to descend, and throughout history, physicians have discussed its entry into the small intestine, bladder, and three jiao channels, having the function of “descending qi” and also being able to “eliminate blood stagnation”, thus clearing the excess heat caused by lower jiao accumulations, making it suitable for use in Bie Jia Jian Wan and Da Huang Zhe Chong Wan. Among the “San Huang”, only Huang Qin is mentioned for treating “phlegm heat”, and since phlegm and blood often bind together, its function of breaking qi and moving blood can also assist in clearing phlegm throughout the body. Formulas like Ben Tun Tang, Wang Bu Liu Xing San, Dang Gui San, Hou’s Black Powder, and Ma Huang Sheng Ma Tang also reflect this unique characteristic of Huang Qin.

Huang Lian treats excess heat in the chest and heart: yang qi is floating, and the qi mechanism desires to rise, with the pulse appearing floating, and the qi and blood being stirred by heat, thus the evil qi is solid and painful when pressed. Therefore, Huang Lian “benefits the gallbladder”, “calms the liver”, and “regulates the stomach” to adjust the rise and fall of the spleen and stomach, clearing excess heat while also “stopping abdominal pain”, addressing both the root and the branch, making it most suitable. Additionally, due to its characteristics in treating gastrointestinal diseases, Zhang Zhongjing combined Huang Lian with Huang Bai, which treats large intestine diseases, in formulas like Wu Mei Wan, Bai Tou Weng Tang, and Bai Tou Weng plus Gan Cao and Ejiao Tang for “long-term diarrhea” and “deficiency diarrhea”. In various Xie Xin Tang cases, the qi mechanism is reversed, with intestinal sounds and diarrhea moving downward, while wheezing, vomiting, dry belching, and sweating move upward, thus both cold and warm are used, one yin and one yang, one rising and one descending. Among cold medicines, Huang Lian and Huang Qin also represent one yin and one yang; Huang Qin is good at promoting qi and tends to drain, while Huang Lian “regulates the stomach”, “thickens the intestines”, and treats “five labor and seven injuries”, tending to tonify. In a single formula, there is yin and yang, and within yin and yang, the principles of Taiji are fully expressed.

Huang Bai can “wash the liver” and treat “jaundice”; its “anti-parasitic” effects may have special relevance to the common parasitic jaundice in the Han Dynasty. Therefore, it is suitable for use in Zhi Zi Bai Pi Tang and Da Huang Niao Shi Tang, and combined with Huang Bai’s ability to treat large intestine diseases, it is most appropriate for use in Wu Mei Wan.

The classification of the “San Huang” based on the three jiao does not truly distinguish the medicinal differences among the three. The historical records of the “San Huang” primarily focus on the symptoms treated, revolving around the “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic”. Among the “San Huang”, their effects on heat syndromes, digestive system diseases, and skin and mucous membrane diseases are similar; both Huang Lian and Huang Bai can regulate the liver and gallbladder, treating heart-related diseases and eye diseases. Huang Qin can “treat dysuria”, “expel water”, “eliminate joint discomfort”, and “eliminate women’s blood stagnation”, excelling at adjusting the qi mechanism for heat syndromes; Huang Lian can “tonify”, “eliminate water”, “benefit bones”, and “stop thirst”, treating the damage to the internal organs caused by excess fire; Huang Bai can also treat intestinal diseases, male and female reproductive system diseases, and has “anti-parasitic” properties.

After the Jin Dynasty, herbal texts elaborated on the “Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic”, emphasizing the properties of the “San Huang” rather than their therapeutic effects. For example, Huang Qin is classified into dried and solid types to explain its functions in the upper and lower jiao, exterior and interior; Huang Lian is explained as clearing heat and drying dampness while draining excess fire to elucidate its functions of “regulating the stomach” and “thickening the intestines”; Huang Bai treats lower limb weakness and explains its treatment of male and female reproductive system diseases by draining excess fire.

Based on the “Shang Han Za Bing Lun”, the classical application of the “San Huang” closely aligns with the understanding of herbal texts before the Song Dynasty, suggesting that modern clinical applications of the “San Huang” should emphasize the experiences recorded in herbal texts before the Song Dynasty. For example, when treating heat-related reproductive system diseases, Huang Bai should be primarily used; if heat dysuria or qi stagnation is present, Huang Qin should be added; if prolonged heat leads to damage to the internal organs, Huang Lian can be added as needed.

医药求真丨菊花、野菊花医药求真丨生姜、干姜、炮姜、高良姜医药求真丨莲,荷叶、莲子、莲子心、藕节、莲蓬、莲须医药求真丨金银花、忍冬藤医药求真丨桑,桑叶、桑枝、桑白皮、桑葚医药求真丨何首乌、夜交藤医药求真丨麻黄、麻黄根医药求真丨枸杞子与地骨皮——果与根医药求真丨芦根、茅根柑橘属中药丨青皮、陈皮(橘红、橘核、橘叶、橘络)、化橘红、枳实、枳壳、香橼、佛手医药求真丨橘核、橘络、橘叶医药求真丨吴茱萸、山茱萸医药求真丨羌活、独活医药求真丨葛根、粉葛、葛花医药求真丨紫苏,苏叶、苏梗、苏子医药求真丨南沙参、北沙参医药求真丨麦冬、天冬医药求真丨瓜蒌、天花粉医药求真丨半夏,姜半夏、法半夏、清半夏、生半夏医药求真丨龙骨、龙齿医药求真丨贝壳类,牡蛎、石决明、蛤壳、蛤壳、珍珠母、瓦楞子、海螵蛸医药求真丨贝母,川贝母、浙贝母医药求真丨海浮石,浮海石、石花医药求真丨兰,佩兰、泽兰医药求真丨白茯苓、赤茯苓、茯神、茯苓皮医药求真丨砂仁、豆蔻、草豆蔻、草果、肉豆蔻医药求真丨白术、苍术医药求真丨香橼、佛手医药求真丨柴胡与前胡、银柴胡医药求真丨参——人参、党参、高丽参、太子参、西洋参、丹参、玄参、苦参甲辰龙年,“龙”字辈中药大盘点医药求真丨青皮、陈皮枳实、枳壳丨小则其性酷而速,大则其性详而缓。桂丨肉桂、桂枝、桂皮医药求真丨陈皮、橘红、化橘红三棱、莪术解一文分清郁金、姜黄、莪术、片姜黄!香附丨气中之血药川芎丨血中气药