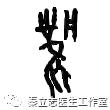

Wind is the messenger of nature; all things in the world cannot be separated from wind. Wind, or the Eight Winds, is a term that refers to the various manifestations of wind. The idiom “coming from all directions” illustrates this concept. Wind is the flow of gas, the transformation between heaven and earth, and a medium for plant reproduction. In the vast universe, wind is the greatest creation. In oracle bone script, wind is written as  and

and  , resembling the shape of a phoenix, indicating that ancient people used “phoenix” and “wind” interchangeably. In the “Shuowen Jiezi,” it is recorded that “wind is the Eight Winds. The east is called Ming Shu Wind, the southeast is Qing Ming Wind, the south is Jing Wind, the southwest is Liang Wind, the west is Chang He Wind, the northwest is Bu Zhou Wind, the north is Guang Mo Wind, and the northeast is Rong Wind. Wind causes insects to move, hence insects transform in eight days.” This shows that ancient people believed wind played a role in changing the seasons; when wind arises, insects move, and all things revive. In spring, as plants awaken and the earth comes to life, wind is regarded as the primary qi of spring. In the theory of the Five Elements, the four seasons are matched with the Five Elements, with spring corresponding to “wood,” and since the liver governs wood, it is said that the liver is the wind wood.

, resembling the shape of a phoenix, indicating that ancient people used “phoenix” and “wind” interchangeably. In the “Shuowen Jiezi,” it is recorded that “wind is the Eight Winds. The east is called Ming Shu Wind, the southeast is Qing Ming Wind, the south is Jing Wind, the southwest is Liang Wind, the west is Chang He Wind, the northwest is Bu Zhou Wind, the north is Guang Mo Wind, and the northeast is Rong Wind. Wind causes insects to move, hence insects transform in eight days.” This shows that ancient people believed wind played a role in changing the seasons; when wind arises, insects move, and all things revive. In spring, as plants awaken and the earth comes to life, wind is regarded as the primary qi of spring. In the theory of the Five Elements, the four seasons are matched with the Five Elements, with spring corresponding to “wood,” and since the liver governs wood, it is said that the liver is the wind wood.

Since wind is the qi of heaven and earth, it constantly changes and fluctuates, and it is not limited to spring; other seasons also experience “wind.” When the changes in wind are particularly strong, even exceeding the primary qi of that season, it can lead to illness, and this wind becomes a pathogenic factor, referred to as wind evil. Wind comes from all directions, with its direction and intensity being unpredictable. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) believes that wind is active; as stated in the “Suwen: Yin Yang Ying Xiang Da Lun,” “When wind prevails, movement occurs.” Therefore, any disease characterized by instability is considered related to “wind,” such as dizziness, tremors, convulsions, and opisthotonos, all of which belong to wind syndrome. It was later recognized that not only does wind exist in nature, but there is also “wind” within the human body, known as liver wind. Since the liver is associated with wind wood, when liver yin is insufficient, liver yang transforms into wind, and internal liver wind movement is very dangerous. Mild cases may present as dizziness, while severe cases can lead to loss of consciousness, which is what we commonly refer to as a “stroke.”

Thus, wind syndrome is also a common clinical diagnosis in TCM, and many diseases exhibit characteristics of wind, leading to the saying that “wind is the leader of a hundred diseases.” Many diseases are named with the addition of “wind,” such as crane knee wind, goose palm wind, and grass shoe wind, named according to animal forms, agricultural relevance, symptoms, locations, and characteristics, such as thunder head wind, shaking head wind, and scrotal wind, as well as color-based names like red travel wind and vitiligo. However, despite the variety, all these diseases are related to wind evil.

In the “Cold Lu Yi Hua,” it is recorded that the famous Qing Dynasty physician Cui Mo’an once treated a newlywed youth who suddenly developed facial swelling, making it difficult for him to open his eyes. Mo’an carefully examined the pulse, diet, and urination but found no clues, leaving him puzzled. Since the journey was long, he began to eat in front of the patient. The youth struggled to open his eyes and looked at him; Mo’an asked, “Do you want to eat?” The patient replied, “I really want to, but the previous doctors forbade me from eating.” Mo’an said, “Why should this illness require fasting?” He immediately had someone bring food for the youth, who ate happily. Mo’an, observing this, was even more puzzled and could not understand the cause of the illness. After much thought, he suddenly noticed that the furniture in the room was all new, with a strong smell of paint. He realized that he should move the patient to another room without new furniture. He then crushed raw crabs and applied them to the patient’s face and body, and after a day or two, the patient fully recovered. This condition is what ancient TCM literature refers to as wind evil, which corresponds to urticaria in Western medicine. Here, “wind” does not refer to the specific wind of nature, but rather a type of “qi”; in this case, it is “paint qi,” as the condition aligns with the characteristics of wind evil, which is “rapid onset and variable changes.” Therefore, this type of condition is also referred to as “wind.” In modern TCM, the rapidly formed lumps on a patient’s body are also called “wind rash lumps.”

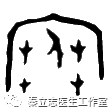

Cold, in bronze script, is written as  , and in small seal script as

, and in small seal script as  . The “Shuowen Jiezi” explains it vividly: “Frozen. It is written with a person under a roof, covered with grass, indicating that the weather is very cold.” Therefore, “cold” is a compound character, indicating a person curled up indoors, using grass to avoid the cold, showing that the weather is very cold.

. The “Shuowen Jiezi” explains it vividly: “Frozen. It is written with a person under a roof, covered with grass, indicating that the weather is very cold.” Therefore, “cold” is a compound character, indicating a person curled up indoors, using grass to avoid the cold, showing that the weather is very cold.

TCM believes that cold governs contraction and pain. Internal cold refers to conditions arising from within, due to the reduced functional activity of the organs, leading to a lack of warmth in the limbs. External cold, as the name suggests, is acquired from the outside, such as dressing too lightly in cold weather. When exposed to external cold, the cold evil binds to the muscle surface, blocking the pores, preventing the defensive qi from dispersing, leading to symptoms of fever, chills, and no sweating; cold evil obstructs the meridians, resulting in pain in the head and body.

The correct principle of health preservation is to keep the head cold and the feet warm. The silk book “Pulse Method” unearthed from the Mawangdui tomb states: “The sage keeps the head cold and the feet warm; the healer takes what is in excess to benefit what is insufficient.” The classic TCM text “Neijing” also states that the pathways of the twelve meridians and the 365 collaterals indicate that the spirit, qi, and blood, especially yang qi, primarily ascend to the head and face, making the head and face the most abundant in yang qi and the most resistant to cold. The famous Tang Dynasty physician Sun Simiao pointed out: “Do not place a stove near the head, as prolonged exposure will lead to fire qi, causing heaviness in the head and redness in the eyes.” Modern TCM practice also follows the principle that the head should be kept cool and not hot.

In contrast to the head, the feet are the area of heavy yin qi. The “Neijing” states: “Yin gathers below, thus the feet are cold.” There is also a saying that “cold rises from the feet.” The “Beiji Qianjin Yaofang” states: “After the first day of the eighth lunar month, warm the feet with a small fire.” Since the lower limbs are most susceptible to cold evil, attention should be paid to keeping the feet warm. A common saying is, “If you want to keep your body safe, do not neglect the Sanli point.” Regular acupuncture or massage of the Sanli (ST36) and Yongquan (KD1) points has good health benefits, promoting the spleen and kidneys to function well, driving away cold and preventing disease.

In real life, following the principle of “cold head,” washing the face with cold water in winter can enhance cold resistance and effectively prevent colds. Many people wash their faces with cold water all year round; some even take a deep breath before immersing their heads in water repeatedly, persisting in this practice, and they do not catch colds throughout the year.

The Tang Dynasty frontier poet Cen Can’s poem “White Snow Song Sending Wu Judge Back to the Capital” describes: “The general’s horn bow cannot be drawn, the protector’s iron armor is too cold to wear. The vast sea is lined with ice a hundred feet thick, gloomy clouds hang heavy over the sky. … Flurries of evening snow fall at the chariot gate, the wind pulls the red flag, freezing it in place.” When snow arrives, the general’s beast horn bow is too hard to draw, and the iron armor is too cold to wear. The desert is crisscrossed with thick ice, and dark clouds hang in the sky. … In the evening, heavy snow falls at the chariot gate, freezing the red flag so that even the fierce wind cannot unfurl it, evoking a sense of bone-chilling cold.

According to the body’s heating needs, the ideal indoor temperature should be what TCM advocates as “cold head, warm feet.” Modern medicine also proves that the capillaries in the feet are fewer, and blood circulation is not as good as in other parts of the body. Especially when the temperature of the feet is low, the whole body feels cold. If this condition persists, blood pressure may rise, leading to other diseases. Therefore, radiant heat is the best heating method, with a uniform indoor temperature that gradually decreases from the bottom up, providing a good feeling of warm feet and a cool head, without causing the circulation of polluted air, keeping the indoor environment clean, thus forming a truly heat environment that meets the body’s heat dissipation requirements, improving blood circulation, promoting metabolism, benefiting cardiovascular diseases, and being particularly suitable for the elderly and children, as well as having certain preventive and therapeutic effects on arthritis and cold legs.

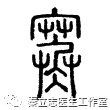

The Han Dynasty “Shu Xing Fu” states: “The poor are clever in the pavilion, the people sleep wet in the dew.” In ancient times, dampness referred to low and wet ground. Dampness, in oracle bone script, is written as  and

and  , resembling the appearance of straw on the ground soaked with water. In the “Zhuangzi: Letting the King” there is a sentence describing the hardships of the people whose houses leak rain, causing the ground to be damp.

, resembling the appearance of straw on the ground soaked with water. In the “Zhuangzi: Letting the King” there is a sentence describing the hardships of the people whose houses leak rain, causing the ground to be damp.

Dampness, with the radical “氵,” is undoubtedly closely related to water. Whether it is damp ground or humid weather, it gives a sticky and uncomfortable feeling. Since water is cold in nature, dampness is also essentially yin. The “Suwen: Tian Yuan Ji Da Lun” states: “Cold, heat, dryness, dampness, wind, and fire are the yin and yang of heaven…” The “cold” and “dampness” mentioned here are climatic factors that exist in nature, and unlike the other climatic factors, wind and dampness can exist in almost any season.

Under normal circumstances, dampness does not significantly affect human health; at most, it may cause discomfort or inconvenience, similar to the humid weather in Shanghai during May and June, where it rains continuously, causing things to become damp and moldy, and a faint odor fills the room, which is disliked by northern people. However, due to different constitutions, some people may be more sensitive to changes in damp weather, especially those with weak spleen and stomach. As mentioned earlier, when the humid weather arrives, many people with weak gastrointestinal systems may experience indigestion and diarrhea. Even without obvious physical discomfort, observing the tongue coating in the mirror may reveal a thick coating.

In the Ming Dynasty, physician Zhao Xianke classified dampness into four types: rain, mist, and dew, which are dampness from the sky; mud and water, which are dampness from the ground; food and drink dampness, and sweat dampness. He also specifically mentioned that different types of dampness lead to completely different diseases. Ancient physicians believed that “the stomach is the sea of water and grain,” and food and drink dampness primarily harms the spleen and stomach. For example, excessive drinking of water or alcohol can lead to vomiting, which is a self-protective response of the stomach when it cannot accommodate such a large amount of food. Eating unclean food can also lead to vomiting and diarrhea, which are manifestations of gastrointestinal discomfort. Moreover, external dampness and dietary dampness can influence each other; if the environment is particularly humid, it is essential to reduce the burden on the stomach and intestines.

Why does the tongue coating appear thick when experiencing damp evil? Because the tongue coating is formed by the qi of the stomach, dampness injures the spleen and stomach, which will be reflected on the tongue coating. The characteristic of dampness is its stickiness and unpleasantness, so the tongue coating appears thick. This is also a reflection of TCM’s holistic view, where even a small phenomenon can reveal a significant issue; as the ancients said, “One leaf falls, and autumn is known,” which illustrates this principle.

Clinical manifestations of dampness obstructing the spleen and stomach, in addition to a thick tongue coating, include more digestive issues. In severe cases, patients may also experience difficulty urinating. One can use herbs that dry dampness and strengthen the spleen, such as Huo Xiang (Agastache), Pei Lan (Eupatorium), and Cang Zhu (Atractylodes) for treatment. The dietary remedy of red bean and crucian carp soup also has excellent health benefits. TCM believes that red beans are neutral in nature, sweet and sour in flavor, and have the effect of clearing heat and detoxifying. Ancient pharmacological texts state that it can “treat edema and skin swelling,” “promote qi and strengthen the spleen and stomach,” and is used for conditions like difficulty urinating and jaundice. Crucian carp is sweet and delicious, has the effect of strengthening the spleen and replenishing deficiency. The “Bencao Shiyi” records that crucian carp “is good for weakness and can be eaten cooked,” while the “Rihua Zibencao” states that it can “warm the middle and promote qi, replenishing deficiency,” and the “Dian Nan Bencao” believes it can “harmonize the five organs and promote blood circulation.” When making red bean and crucian carp soup, first soak three taels of red beans for about half an hour, then cook them with the crucian carp in a clay pot with clear water, adding a little seasoning for a light flavor. Drinking the soup and eating the fish is very effective during humid weather. Nowadays, many office buildings use central air conditioning, creating a cold and damp environment in summer. Many white-collar workers feel dizzy, shoulder pain, and poor appetite after a day of work. Cooking red bean and crucian carp soup at home not only provides protein but also benefits the spleen and stomach while replenishing moisture, achieving three benefits in one, making it worth a try.

Dryness, in small seal script, is written as  . The “Shuowen Jiezi” explains this character as “dry,” while the “Yupian” states “dry means dry.” In ancient literature, dry and arid are often used interchangeably to indicate a state of lacking or missing moisture. The “I Ching: Qian Hexagram: Wen Yan” explains dryness as “water flows wet, fire becomes dry,” with Kong Yingda’s commentary stating, “These two are mutually influenced by their forms. Water flows to the ground, first to the wet places; fire burns its fuel, first to the dry places,” thus, dryness is “from fire” (“Shuowen Jiezi”). This shows that the meanings of dry and arid contain the ancient people’s early understanding of water and fire, dry and wet. The “Huainanzi,” written in the early Western Han Dynasty, also applies “dry” to describe climatic phenomena, stating, “Dryness, dampness, cold, and heat arrive with the seasons, sweet rain and dew fall at the right time,” and classifies dryness clearly, stating, “Jiazi qi is dry and turbid, Bingzi qi is dry and yang, Wuzi qi is damp and turbid, Gengzi qi is dry and cold, and Renzi qi is clear and cold.”

. The “Shuowen Jiezi” explains this character as “dry,” while the “Yupian” states “dry means dry.” In ancient literature, dry and arid are often used interchangeably to indicate a state of lacking or missing moisture. The “I Ching: Qian Hexagram: Wen Yan” explains dryness as “water flows wet, fire becomes dry,” with Kong Yingda’s commentary stating, “These two are mutually influenced by their forms. Water flows to the ground, first to the wet places; fire burns its fuel, first to the dry places,” thus, dryness is “from fire” (“Shuowen Jiezi”). This shows that the meanings of dry and arid contain the ancient people’s early understanding of water and fire, dry and wet. The “Huainanzi,” written in the early Western Han Dynasty, also applies “dry” to describe climatic phenomena, stating, “Dryness, dampness, cold, and heat arrive with the seasons, sweet rain and dew fall at the right time,” and classifies dryness clearly, stating, “Jiazi qi is dry and turbid, Bingzi qi is dry and yang, Wuzi qi is damp and turbid, Gengzi qi is dry and cold, and Renzi qi is clear and cold.”

TCM theory has also incorporated these ancient understandings of dryness. The “Neijing” systematically and clearly discusses the relationship between dryness and human life phenomena. The TCM theory of “dryness” is based on the understanding of the natural world’s “four seasons” and “six qi.” The “four seasons” refer to spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The theory of the four seasons posits that as the yin qi of heaven and earth returns to the earth in autumn, the climate cools, and the yin qi gathers, promoting the maturation and fruition of plants. The main characteristic of this season is the gradual increase of yin qi and the decline of yang qi. However, among the two seasons of autumn and winter, autumn is the season when yin qi begins to grow, thus it is the yang within yin. At this time, the physiological activities of the human body also begin to contract and descend with the onset of autumn, the pores begin to close, and the skin’s hair follicles start to constrict. The “six qi” refers to the six climatic characteristics of wind, cold, heat, dampness, dryness, and fire that appear in different seasons. Every year after the “Beginning of Autumn” solar term, not only does the air temperature begin to drop, but the amount of water produced on the earth also begins to decrease, with humidity and rainfall significantly lower than in summer. Therefore, autumn is characterized by clear skies and refreshing air. After the “Cold Dew” solar term, the autumn wind begins to rise, and the air becomes increasingly dry. Thus, TCM theory holds that “dryness” is the primary qi of autumn. In daily life, we often feel that our nasal passages are drier in autumn, and there may even be blood streaks, with the throat frequently experiencing dryness and cough, sometimes with a small amount of phlegm, yet it is difficult to cough it out, and the lips are prone to cracking. TCM believes these are manifestations of “autumn dryness,” primarily caused by the “dryness” of the season leading to the evaporation of moisture from the upper respiratory mucosa and the skin’s surface.

“Autumn dryness” is a seasonal qi that generally does not cause illness. However, if the dryness qi is excessive or if “its qi exists out of season,” it can easily transform into dryness evil, harming the body and leading to disease. Dryness evil can harm the skin and hair, leading to symptoms such as fever, chills, and headache. If it invades the upper orifices, it can cause dryness in the mouth, nose, and throat. Dryness evil most easily harms the lungs, potentially causing “autumn dry cough syndrome,” which can be divided into “cool dryness” and “warm dryness.” The clinical manifestations of cool dryness include chills, no sweating, slight headache, cough with thin phlegm, mild thirst, dry nose and throat, white and dry tongue, and a wiry pulse. The main clinical manifestations of warm dryness include fever, slight aversion to wind and cold, headache, little sweating, thirst, dryness of the mouth, nose, and throat, dry cough with little phlegm, irritability, dry and bitter yellow tongue, and a rapid pulse.

To prevent and treat “autumn dryness,” nourishing yin and benefiting qi is key. At this time, one should avoid spicy foods such as scallions, ginger, chili, and pepper to prevent exacerbating lung heat symptoms. From the perspective of TCM’s five elements, the lung belongs to metal, and the liver belongs to wood; when metal is strong, it can damage wood, thus harming the liver. Therefore, it is advisable to consume some sour foods, as “sour enters the liver,” which can strengthen liver wood and prevent excessive lung qi from damaging the liver. Sour foods can help to restrain liver qi and protect the liver, but moderation is essential, as many sour foods like vinegar and sour plums can irritate the stomach, leading to ulcers and gastritis. In autumn, as yin qi increases and temperatures drop, if one consumes too many cold and damp fruits and vegetables, it can exacerbate the situation, leading to insufficient yang qi, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. In the five elements’ generating and overcoming relationships, if the spleen earth is harmed, it cannot generate metal, thus the lung metal is also harmed, which is not conducive to health in autumn. Therefore, one should avoid excessively cold and damp foods to protect the stomach and lungs. Adequate water intake is an essential maintenance measure to moisten dryness and prevent dryness in autumn. Drinking water should not be neglected, and the method should be appropriate, with small amounts consumed frequently being preferable to large amounts at once. Drinking large quantities at once can burden the stomach and intestines, causing discomfort; only small, slow sips can effectively moisten the mouth, nose, throat, esophagus, and even the trachea. In addition, nourishing qi and yin should include foods like yam, lily, tremella, pig’s trotters, lotus seeds, lotus root, pears, and goji berries.

Learning to use fire is a significant advancement in human civilization. In ancient times, people in different regions created deities to guide humanity in utilizing “fire” and gave them considerable respect. Suiren and Zhu Rong are the famous fire ancestors and fire gods in Chinese legend. “Fire” is the light and flame produced when a substance burns. In oracle bone script, fire resembles the shape of a blazing flame  , while ancient pottery script depicts fire as a built fire pit

, while ancient pottery script depicts fire as a built fire pit  . Although the character for fire has undergone changes over time, its shape still reflects the appearance of burning firewood. Fire holds an important position in the five elements, belonging to the “yang of yang,” as fire is characterized by its upward nature, thus many things associated with fire occupy higher positions, such as the sun. Regarding the cardinal directions, the “Ancient Text Shangshu” considers “fire” to be in the center, controlling other directions; the “Modern Text Shangshu” believes “fire” is in the south, consistent with its hot nature. It is now generally accepted that “fire” governs the south. In the human body, fire is closely related to the heart, which is considered the monarch. The “Suwen: Six Sections of the Zang Xiang Theory” states: “The heart is… the sun among the yang, connected to the summer qi.” The heart is the governing organ, overseeing the functional activities of all five organs and six bowels, and presiding over mental consciousness and cognitive activities, thus heart fire is also referred to as monarch fire. The yang qi in the kidneys is called kidney yang, also known as the fire of the life gate, and is referred to as kidney fire or mutual fire. Kidney yang is the root of the body’s yang qi, inherent from birth, and is the driving force of life. Mutual fire has many names, such as dragon fire, thunder fire, and dragon thunder fire, all of which are different perspectives on understanding and naming mutual fire. The “Suwen: Tian Yuan Ji Da Lun” states: “Monarch fire is for illumination, mutual fire is for position.” This means the heart is the monarch, the kidney is the root, monarch fire is for use, and mutual fire is for the root. Mutual fire must operate under the command of monarch fire to function normally. When monarch fire is in its proper state, the spirit is clear; mutual fire should be concealed and not exposed, hence it is said that mutual fire is for position. Fire has a warming function; if a patient presents with cold fingers, dull pain in the lower abdomen, or pale menstrual flow, it often indicates insufficient yang qi. The relationship between yang qi and mutual fire is very close, and in clinical practice, warming and tonifying herbs like Lu Jiao Shuang (Deer Antler Velvet) and Ba Ji Tian (Morinda Root) are often used. If male patients exhibit symptoms of impotence, TCM often considers it a decline of the life gate fire, treating it with methods to warm the kidneys and strengthen yang.

. Although the character for fire has undergone changes over time, its shape still reflects the appearance of burning firewood. Fire holds an important position in the five elements, belonging to the “yang of yang,” as fire is characterized by its upward nature, thus many things associated with fire occupy higher positions, such as the sun. Regarding the cardinal directions, the “Ancient Text Shangshu” considers “fire” to be in the center, controlling other directions; the “Modern Text Shangshu” believes “fire” is in the south, consistent with its hot nature. It is now generally accepted that “fire” governs the south. In the human body, fire is closely related to the heart, which is considered the monarch. The “Suwen: Six Sections of the Zang Xiang Theory” states: “The heart is… the sun among the yang, connected to the summer qi.” The heart is the governing organ, overseeing the functional activities of all five organs and six bowels, and presiding over mental consciousness and cognitive activities, thus heart fire is also referred to as monarch fire. The yang qi in the kidneys is called kidney yang, also known as the fire of the life gate, and is referred to as kidney fire or mutual fire. Kidney yang is the root of the body’s yang qi, inherent from birth, and is the driving force of life. Mutual fire has many names, such as dragon fire, thunder fire, and dragon thunder fire, all of which are different perspectives on understanding and naming mutual fire. The “Suwen: Tian Yuan Ji Da Lun” states: “Monarch fire is for illumination, mutual fire is for position.” This means the heart is the monarch, the kidney is the root, monarch fire is for use, and mutual fire is for the root. Mutual fire must operate under the command of monarch fire to function normally. When monarch fire is in its proper state, the spirit is clear; mutual fire should be concealed and not exposed, hence it is said that mutual fire is for position. Fire has a warming function; if a patient presents with cold fingers, dull pain in the lower abdomen, or pale menstrual flow, it often indicates insufficient yang qi. The relationship between yang qi and mutual fire is very close, and in clinical practice, warming and tonifying herbs like Lu Jiao Shuang (Deer Antler Velvet) and Ba Ji Tian (Morinda Root) are often used. If male patients exhibit symptoms of impotence, TCM often considers it a decline of the life gate fire, treating it with methods to warm the kidneys and strengthen yang.

In summary, fire holds an important position not only in nature but also as the driving force of life activities in the human body. Under normal conditions, the life “fire” provides lasting warmth and support to the body.