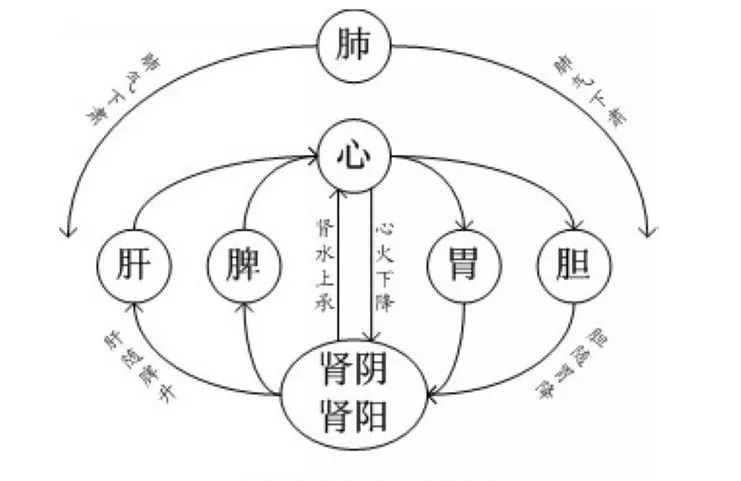

Huang Yuanyu’s Diagram of Qi Mechanism Ascending and Descending

The Relationship Between the Five Zang Organs and Six Fu Organs

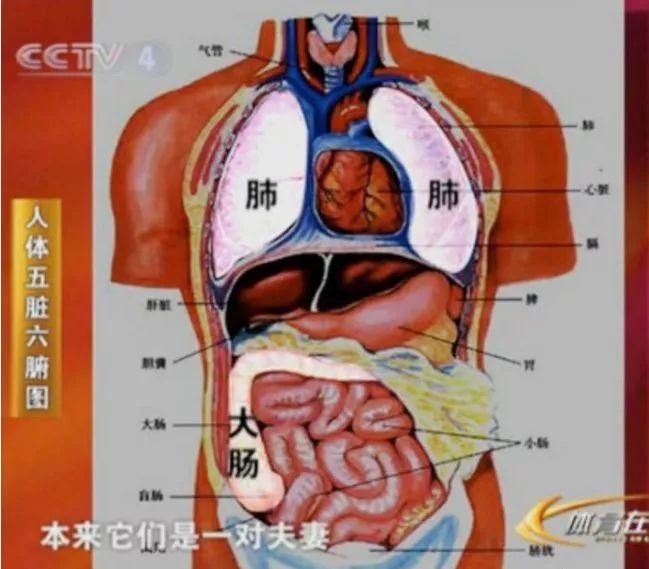

“Zang” refers to solid organs, including the heart (xin), liver (gan), spleen (pi), lungs (fei), and kidneys (shen). “Fu” refers to hollow organs, including the small intestine (xiao chang), gallbladder (dan), stomach (wei), large intestine (da chang), and bladder (pang guang), which correspond to the five zang organs. Additionally, the thoracic and abdominal cavities are divided into the upper jiao (shang jiao), middle jiao (zhong jiao), and lower jiao (xia jiao), which is considered the sixth fu organ.

[The Relationship Between Zang Organs]

1. Heart and Lungs: The heart governs blood, while the lungs govern qi. The maintenance of organ function relies on the circulation of qi and blood to deliver nutrients. Although the normal flow of blood is governed by the heart, it must be propelled by lung qi. The ancestral qi stored in the lungs must nourish the heart vessels to ensure smooth circulation throughout the body.

2. Heart and Liver: The heart is the driving force of blood circulation, while the liver is an important organ for blood storage. Therefore, when heart blood is abundant, liver blood is also plentiful, nourishing the tendons and promoting normal activity of the limbs and body. If heart blood is deficient, it can lead to insufficient liver blood, resulting in symptoms such as muscle and bone pain, limb spasms, and convulsions. Additionally, liver qi stagnation can generate heat, affecting the heart and causing irritability and insomnia.

3. Heart and Spleen: The essence transformed by the spleen requires the circulation of blood to be distributed throughout the body. Heart blood must rely on the water and grain essence absorbed and transported by the spleen. Furthermore, the heart governs blood, and the spleen regulates blood; normal spleen function is essential for blood regulation. If spleen qi is weak, it can lead to blood not following its proper channels.

4. Heart and Kidneys: The heart and kidneys interact and constrain each other to maintain a relative balance of physiological functions. Under physiological conditions, heart yang continuously descends while kidney yin continuously ascends, creating a harmonious interaction known as “heart-kidney intersection.” In pathological conditions, if kidney yin is insufficient and cannot ascend to nourish the heart, it can lead to excessive heart yang, resulting in disharmony known as “heart-kidney disconnection.”

5. Liver and Spleen: The liver stores blood, while the spleen governs the transformation of water and grain essence into blood. If spleen deficiency affects blood production, it can lead to insufficient liver blood, resulting in dizziness, blurred vision, and other symptoms. The liver prefers smooth flow and dislikes stagnation; if liver qi is stagnant and counteracts the spleen, it can lead to abdominal pain and diarrhea.

6. Liver and Lungs: The liver meridian connects to the lungs, establishing a relationship between the two. When liver qi ascends, lung qi descends, affecting the rise and fall of qi in the body. If liver qi ascends excessively, lung qi may fail to descend, leading to symptoms such as chest tightness and shortness of breath. If liver fire invades the lungs, symptoms such as chest and rib pain, dry cough, or blood-streaked phlegm may occur.

7. Liver and Kidneys: The kidneys store essence, while the liver stores blood. Liver blood relies on kidney essence for nourishment, and kidney essence requires continuous supplementation from liver blood; they are interdependent and mutually supportive. Insufficient kidney essence can lead to liver blood deficiency. Conversely, liver blood deficiency can affect kidney essence production. If kidney yin is insufficient, the liver may lose nourishment, leading to liver yin deficiency, resulting in symptoms such as excessive liver yang or internal wind, including dizziness, tinnitus, tremors, numbness, and convulsions.

8. Lungs and Spleen: The spleen transports the essence of water and grain to the lungs, combining with the essence inhaled by the lungs to form ancestral qi (also known as lung qi). The strength of lung qi is related to the spleen’s ability to transform essence; thus, strong spleen qi leads to abundant lung qi. When spleen deficiency affects the lungs, symptoms such as reduced appetite, reluctance to speak, loose stools, and cough may appear. Clinically, the method of “tonifying the spleen and benefiting the lungs” is often used for treatment. For example, in cases of chronic cough with copious, thin, white phlegm that is easily expectorated, along with fatigue and reduced appetite, although the disease manifests in the lungs, the root cause lies in the spleen, necessitating the use of methods to “strengthen the spleen, dry dampness, and transform phlegm” for effective treatment. The saying “the lungs are the storage for phlegm, while the spleen is the source of phlegm” reflects the relationship between the spleen and lungs.

9. Spleen and Kidneys: Spleen yang relies on kidney yang for warmth to perform its transformation function. Insufficient kidney yang can weaken spleen yang, leading to abnormal transformation and resulting in symptoms such as morning diarrhea and undigested food. Conversely, if spleen yang is weak, it can also lead to insufficient kidney yang, resulting in symptoms such as lower back pain, cold extremities, and edema.

10. Lungs and Kidneys: The lungs govern descent and regulate the water pathways, allowing water and fluids to return to the kidneys. The kidneys govern water and fluids, and through kidney yang’s vaporization, the purest essence rises to the lungs, relying on spleen yang’s transformation to complete the function of water and fluid metabolism. The lungs, spleen, and kidneys are interconnected; dysfunction in one organ can lead to water retention and edema. The lungs govern respiration, while the kidneys govern qi intake, and both organs work together to maintain the rise and fall of qi in the body.

Diagram of the Five Zang Organs and Six Fu Organs

[The Relationship Between Zang and Fu]

The zang and fu organs are mutually supportive, with each zang corresponding to a fu. Zang organs are yin and internal, while fu organs are yang and external. The relationship between zang and fu is connected through the meridians; the meridians of the zang connect to the fu, and the meridians of the fu connect to the zang, allowing for mutual influence and interaction. Therefore, changes in one can affect the other.

The relationship between zang and fu is as follows: Heart and Small Intestine; Liver and Gallbladder; Spleen and Stomach; Lungs and Large Intestine; Kidneys and Bladder; Pericardium and San Jiao.

1. Heart and Small Intestine: The meridians are interconnected, mutually corresponding. If there is heat in the heart meridian, it can lead to sores on the tongue. If heat from the heart moves to the small intestine, symptoms such as short, red urination and painful urination may occur.

2. Liver and Gallbladder: The gallbladder is housed in the liver, and the zang and fu are interconnected through the meridians. Bile originates from the liver; if liver function is impaired, it can affect normal bile secretion. Conversely, abnormal bile secretion can also affect the liver. Therefore, liver and gallbladder symptoms often occur simultaneously, such as jaundice, rib pain, bitter taste in the mouth, and dizziness.

3. Spleen and Stomach: In terms of characteristics, the spleen prefers dryness and dislikes dampness, while the stomach prefers moisture and dislikes dryness; the spleen governs upward movement, while the stomach governs downward movement. In terms of physiological function, the stomach is the sea of water and grain, responsible for digestion; the spleen governs the transportation of the stomach’s fluids and is responsible for transformation. The two work together to complete the tasks of digestion, absorption, and transportation of water and grain.

The stomach qi must descend smoothly; if stomach qi does not descend and instead ascends, symptoms such as nausea and vomiting may occur. If spleen qi does not ascend and instead sinks, symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, prolapse of the rectum, and uterine prolapse may occur. Due to the close relationship between the spleen and stomach physiologically, they mutually influence each other pathologically, so in clinical practice, the spleen and stomach are often discussed together, and treatments often address both.

4. Lungs and Large Intestine: The meridians are connected, mutually corresponding. If lung qi descends, the large intestine’s qi can flow smoothly, allowing it to perform its function of transmission. Conversely, if the large intestine maintains its transmission, lung qi can descend. For example, if lung qi is stagnant and loses its descending function, it may lead to obstruction in the large intestine’s transmission, resulting in constipation. Conversely, obstruction in the large intestine can lead to abnormal lung qi descent, resulting in shortness of breath and cough. Additionally, in treatment, if there is excess heat in the lungs, it can be purged through the large intestine, allowing heat to be expelled. Conversely, if the large intestine is obstructed, it can help clear lung qi to facilitate the large intestine’s qi flow.

5. Kidneys and Bladder: The meridians are interconnected, mutually corresponding. Physiologically, one is a water zang and the other a water fu, working together to maintain the balance of water metabolism (with the kidneys being the primary organ). Kidney yang vaporizes, allowing water to seep into the bladder, which then expels urine through its own function, aided by kidney yang. Pathologically, insufficient kidney yang can weaken bladder function, leading to frequent urination or incontinence; bladder damp-heat can also affect the kidneys, resulting in symptoms such as lower back pain and hematuria.

6. Pericardium and San Jiao: The meridians are interconnected, mutually corresponding. For example, in clinical practice, in cases of febrile diseases with damp-heat combined evil, if it lingers in the San Jiao, symptoms such as chest tightness, heaviness in the body, and reduced urination may appear, indicating that the disease is in the qi level. If its progression is not halted, the warm-heat pathogen may enter the nutrient level from the qi level, penetrating the pericardium from the San Jiao, leading to symptoms such as coma and delirium.