Floating (Yang)

The floating pulse (fu mai), when lifted, is abundant, but when pressed, it is insufficient (from the “Pulse Classic”). It resembles the feathers on a bird’s back being lightly blown by a breeze, appearing light and floating (qīng fàn mào), like following the elm pods (from the “Suwen”), like wood floating on water (Cui’s description), or like twisting scallion leaves (Li’s description). The floating pulse indicates a light and clear presence above, represented by the Qian hexagram, associated with autumn, and linked to the lungs, also referred to as ‘fur’. If excessive, it becomes firm in the center and empty on the sides, resembling following chicken feathers, indicating an external illness. If insufficient, the qi comes lightly and weakly, indicating an internal illness. The “Pulse Treatise” states that if it resembles excessive, it is a combination of floating and surging tightness, not merely a floating pulse.

“Body Condition Poem” states that the floating pulse only travels along the flesh, like following elm pods appearing light. In the third autumn, if it is known to be well, it can be alarming if encountered after a long illness.

“Similarities Poem” describes the floating pulse as wood floating in water, large and hollow is a Kōu pulse. If it floats lightly, it is a surging pulse; although it comes strong, it leaves slowly. The floating pulse is light and flat like twisting scallions. If it comes weakly, it is large and empty. Floating and soft indicates a Rú pulse, scattered like willow fluff with no fixed trace. Floating and strong indicates a Hóng pulse, floating and slow indicates a Xū pulse, excessively weak indicates a Sàn pulse, floating and weak indicates a Kōu pulse, floating and soft indicates a Rú pulse.

“Main Disease Poem” states that the floating pulse indicates exterior Yang diseases, with slow wind, rapid heat, tight cold, and constrained cold. A strong floating pulse indicates much wind-heat, while a weak floating pulse indicates blood deficiency. A floating pulse at the inch position indicates headache and dizziness from wind, or there may be phlegm and wind gathering in the chest. The guan position indicates earth deficiency combined with wood excess, while the chi position indicates urinary flow issues.

The floating pulse indicates exterior conditions; a strong pulse indicates excess, while a weak pulse indicates deficiency. A floating and slow pulse indicates wind, a floating and rapid pulse indicates wind-heat, a floating and tight pulse indicates wind-cold, a floating and slow pulse indicates wind-damp, a floating and weak pulse indicates heat from summer damage, a floating and Kōu pulse indicates blood loss, a floating and Hóng pulse indicates empty heat, and a floating and Sàn pulse indicates exhaustion.

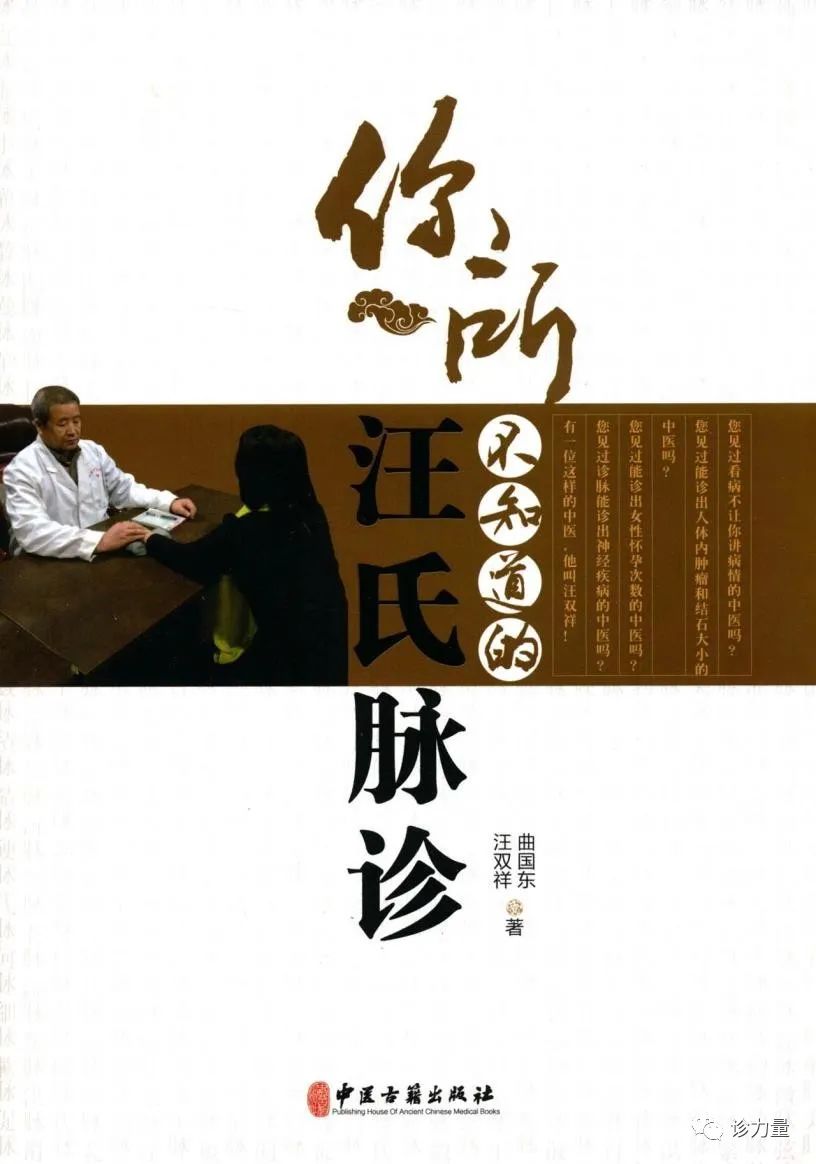

The pulse image refers to the shape and dynamics of the pulse, including frequency, rhythm, morphology, and fullness, serving as one of the bases for TCM diagnosis, which is highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine. The pulse taking we commonly refer to is the assessment of the patient’s pulse image. The pulse image has been recorded in many ancient Chinese medical texts. Wang Shuhe in the Jin Dynasty summarized the pulse images into twenty-four types in the “Pulse Classic”. In the Ming Dynasty, Li Shizhen expanded upon the twenty-four pulses in the “Pulse Classic” and added three more types in his work “Binhulu Pulse Studies”, bringing the total to twenty-seven types. Li Zhongzi in the Ming Dynasty further added disease pulses in the “Zhenjia Zhengyan”, resulting in a total of twenty-eight pulse types, which have been widely used in later generations. Most TCM practitioners are familiar with these twenty-eight pulse types and use them as a basis for diagnosing diseases. However, the pulse images are not limited to these twenty-eight types; ancient physicians also summarized an additional fifteen pulse types, which hold significant importance in clinical diagnosis. Unfortunately, these fifteen pulse types are less known, and very few TCM doctors can master and apply them in practice. For these fifteen pulse types, Wang Shuangxiang, through years of practice treating patients, has carefully experienced and studied them. After extensive case studies and years of effort, he has finally been able to correlate these fifteen pulse types with the patients’ symptoms. Therefore, Wang Shuangxiang is not only proficient in the commonly used twenty-eight pulse types but also has profound insights into the lesser-known fifteen pulse types. In recent decades, with social development, many issues such as environmental pollution, food safety, and antibiotic abuse have emerged, leading to changes in human cells and unexpected diseases and chronic conditions, resulting in significant changes in constitution reflected in the pulse. Wang Shuangxiang has dedicated himself to research, drawing on over forty years of experience and clinical insights, innovating and promoting based on inheritance, making many new discoveries on the basis of predecessors’ understanding of these pulse types. He has combined the commonly used twenty-eight pulse types with the less common fifteen pulse types, enabling him to skillfully use forty-three pulses to diagnose diseases, refining the categories of pulse images for specific symptoms and expanding the coverage of pulse diagnosis. Notably, Wang Shuangxiang can correlate these forty-three pulse types with Western medical diseases, allowing him to directly determine what Western medicine refers to as certain diseases or issues based on these pulse types. This is a groundbreaking contribution, akin to building a convenient bridge in the practice of integrating Chinese and Western medicine, representing a precious achievement of his long career.

The fifteen lesser-known pulse types are as follows: Màn pulse, Xiǎo pulse, Jiān pulse, Guàn pulse, Chuán pulse, Bó pulse, Jī pulse, Yìng pulse, Hé pulse, Ruǎn pulse, Dà pulse, Fǔ pulse, Wén pulse, Xiè pulse, Chōng pulse. Regarding the characteristics of these fifteen pulse types, Wang Shuangxiang provided a rough explanation based on his practice and insights, which I have organized as follows:(1) Màn pulseIn 1985 and 1986, during the process of diagnosing patients, Wang Shuangxiang realized the Màn pulse. The Màn pulse is characterized by a pulse that is very laborious and obstructed under normal qi and blood circulation and respiration, akin to a vehicle struggling on a wide road.(2) Xiǎo pulseThe Xiǎo pulse is finer than the fine pulse; it is delicate, while the fine pulse is coarse, chaotic, and prickly. The Xiǎo pulse is precise, appearing as continuously connected fine and small, making it difficult to discern. The Xiǎo pulse appears when a patient has multiple fibroids.For Wang Shuangxiang, the Xiǎo pulse is particularly significant in diagnosing diseases such as lung cancer, uterine fibroids, rectal polyps, pancreatic cancer, cholecystitis, stones, prostate changes, and gastric mucosal changes.(3) Jiān pulseBetween 1979 and 1981, Wang Shuangxiang identified the Jiān pulse in the pulse images of some fibroid patients. As the name suggests, the Jiān pulse is particularly sharp, like a needle point, causing discomfort when touched. The Jiān pulse reflects uterine fibroids and various fibroid conditions.(4) Guàn pulseIn 1989, Wang Shuangxiang began diagnosing patients through the Guàn pulse. How to describe the Guàn pulse? It is like using a large pump to irrigate a field, forcefully pushing water up. If the pulse vessel walls are thick and large, it resembles a pump pushing blood up, indicating high blood pressure. The arterial walls cannot withstand this pressure, leading to bleeding and swelling. High blood pressure, myocardial infarction, and cerebral hemorrhage are associated with the Guàn pulse. Previously, there was no term for Guàn pulse; it was referred to as a stroke.The discovery of the Guàn pulse is significant; it can indicate if a patient will experience a cerebral hemorrhage within a month to three months or three years later.(5) Chuán pulseThe Chuán pulse conveys information. This pulse type indicates the nature of information transmission; for instance, if a certain disease has not yet manifested, it can already be detected. This prompts attention to the causes of the disease and what lifestyle or dietary changes should be made.The Chuán pulse manifests as a pulse that continuously follows, with irregular thickness, sometimes thick and sometimes thin, with some areas lacking blood flow while others feel hard, indicating abnormal transmission with signs of disconnection. The Chuán pulse plays a significant role in the prevention of diseases.(6) Bó pulseThe Bó pulse appears in patients with cardiovascular diseases who have long-term taken antihypertensive medications, indicating symptoms of hypertension, myocardial infarction, cerebral thrombosis, and cerebral hemorrhage.(7) Jī pulseThe Jī pulse arises from excessive eating and drinking, accumulating a lot of greasy blood lipids and cholesterol, causing abnormal obstruction and expansion of blood vessels.It manifests in the pulse as blockages and residues that cannot be expelled during pulse taking. Patients who frequently take medications may also exhibit the Jī pulse due to excessive intake of hormones and antibiotics, leading to impurities accumulating in the vessel walls.(8) Yìng pulseThe Yìng pulse appears in cases of arterial sclerosis in cardiovascular diseases. The pulse feels particularly hard, like a lack of calcium, and cannot be pressed down; this is the Yìng pulse, which may indicate imminent cerebral thrombosis or myocardial infarction. The Yìng pulse differs from the Guàn pulse; the Guàn pulse has disconnections, while the Yìng pulse is always full, with no empty sections in the vessel walls, all being swollen.(9) Hé pulseWang Shuangxiang took three years to comprehend the Hé pulse. The Hé pulse arises from poor rest and excessive fatigue, or irregular dietary habits, leading to heart and cerebellar fatigue, resulting in the Hé pulse. In this case, the cells are normal, and blood circulation within the cell nucleus is normal, but the patient feels weak, has poor sleep quality, and experiences palpitations. Wang Shuangxiang sometimes tells patients that they do not need medication; changing their daily routine and dietary habits can improve their condition. This pulse is the Hé pulse.(10) Ruǎn pulseThe Ruǎn pulse indicates a lack of desire for movement in qi and blood, but functionally, it must move, leading to both qi and blood deficiency. Generally, this qi and blood issue arises from laziness; those who exercise regularly will not exhibit the Ruǎn pulse. The Ruǎn pulse does not equate to blood deficiency; there is still blood in the vessel walls, but it is reluctant to move, indicating low elasticity and function, with cells lacking vitality. To improve this condition, one must exercise and avoid laziness, which will gradually improve.(11) Dà pulseThe Dà pulse generally indicates tuberculosis, malignant tumors, and also appears in cases of abscesses, colds, and typhoid.(12) Fǔ pulseThe appearance of the Fǔ pulse indicates that the five organs and six bowels contain a large amount of acute conditions and diseases, where medication is often inappropriate, and no treatment is effective, leading to recurring issues. This phenomenon is called the Fǔ pulse. The cause of the Fǔ pulse is incorrect diagnosis and treatment, with the patient experiencing both qi and blood deficiency, weakness in the limbs, and overall illness. The pulse appears as if it is present yet faint, like a shadow.(13) Wén pulseThe Wén pulse is quite unique; it moves steadily, neither jumping nor erratic, neither coarse nor fine, but rather coherent and stable, yet there is stagnation in qi and blood, resulting in numerous small blockages. As long as these small blockages are resolved, symptoms like headaches, dizziness, and confusion will not occur. Western medicine refers to this condition as Ménière’s syndrome.(14) Xiè pulseThe Xiè pulse appears when one has long-term consumed unsuitable foods, manifesting during enteritis and diarrhea. In the pulse, the Xiè pulse shows that the pulse cannot keep up, with qi and blood unable to rise, indicating insufficient stomach qi and spleen deficiency leading to diarrhea.(15) Chōng pulseThe Chōng pulse is characterized by being sharp, fast, and chaotic, resembling a surge upwards. This pulse type represents neurological headaches, cervical hyperplasia, breast hyperplasia, breast lymphadenitis, lung lymphatics, and lung cysts.For many years, Wang Shuangxiang has been known as a master of pulse diagnosis, often diagnosing conditions without the patient speaking, stating, “The patient does not speak, yet I can discern eight or nine of their conditions through pulse diagnosis,” even identifying minute fibroids that instruments cannot detect, with sizes accurate to a fraction of a millimeter. These astonishing feats stem from his mastery of the traditional twenty-eight pulse types and his proficient understanding of these lesser-known fifteen pulse types. These forty-three pulse types have helped him clearly, accurately, and swiftly identify various conditions, encapsulating the essence of his years of practical experience, hard work, and wisdom. In fact, what is often termed a miracle is mostly the result of hard work.