Pulse diagnosis includes pulse taking and palpation. The ancient method of pulse taking was comprehensive, but since the “Nanjing” (Classic of Difficult Issues), it has focused on the cun (寸) position. All pulses converge at the lungs, hence the cun position is more reflective of the overall condition of the body. Clinical verification shows that the changes in pulse correlate closely with the variations in qi and blood. The “Jingyue Quanshu” states: “The color of the pulse is the shadow of blood and qi. If the form is correct, the shadow is correct; if the form is slanted, the shadow is slanted. If disease arises internally, the pulse color must be seen externally; therefore, anyone examining a disease must first clarify the pulse color.” Palpation was first mentioned in the “Neijing” (Inner Canon), where the “Lingshu” (Spiritual Pivot) states: “Only adjust the chi (尺) to discuss the disease.” Later generations expanded this to include palpation of the hands and feet, muscle surfaces, and the chest and abdomen. We will discuss pulse diagnosis and palpation separately.

(1) Pulse Diagnosis

Pulse diagnosis is a relatively difficult diagnostic technique. As stated in the “Chushi Yishu”: “Broadly involved in understanding diseases, frequently diagnosing and recognizing pulses, repeatedly using effective medicines.” This means that one must practice pulse taking repeatedly to discern complex pulse patterns.

Pulse taking focuses on the cun position, located at the wrist of both hands, with the back of the hand opposite the high bone as the guan (关) position. The area before the guan is the cun (寸) position, and the area behind is the chi (尺) position. Each position is further divided into three levels: superficial, middle, and deep, collectively referred to as the “three positions and nine levels”. The cun, guan, and chi positions correspond to the organs: left cun corresponds to the heart, pericardium as the outer defense of the heart, small intestine and heart are interrelated, hence they are examined at the same position; left guan corresponds to the liver and gallbladder; left chi corresponds to the kidneys and bladder. Right cun corresponds to the lungs and large intestine; right guan corresponds to the spleen and stomach; right chi corresponds to the mingmen (命门) and sanjiao (三焦).

When diagnosing the pulse, one must concentrate, breathe evenly, and position the fingers appropriately. The patient should lay their palm flat. The techniques for feeling the pulse are: light touch is called “ju” (举), heavy touch is called “an” (按), moderate touch is called “hou” (候), and probing is called “xun” (寻). There are also fixed descriptions for pulse positions: moving from the chi position to the cun position is called “shang” (上), moving from the cun position to the chi position is called “xia” (下); moving from the flesh to the skin is called “lai” (来), moving from the skin back to the flesh is called “qu” (去); the pulse reaching the finger is called “zhi” (至), and stopping is called “zhi” (止). To measure changes in pulse patterns, one must also discuss the normal pulse patterns, which are divided into three states: stomach (胃), spirit (神), and root (根).

1. Stomach (胃) — Refers to the pulse having stomach qi, with a uniform and gentle appearance. If it is excessively superficial or deep, or fluctuates between fast and slow, it indicates a lack of stomach qi.

2. Spirit (神) — Refers to the pulse having spirit qi, with a smooth and glossy appearance under the fingers. If it is hard and stiff against the fingers, it indicates a lack of spirit qi.

3. Root (根) — Refers to the pulse having a solid foundation, with a persistent presence when pressed. If it becomes loose after prolonged pressure, it indicates a lack of root.

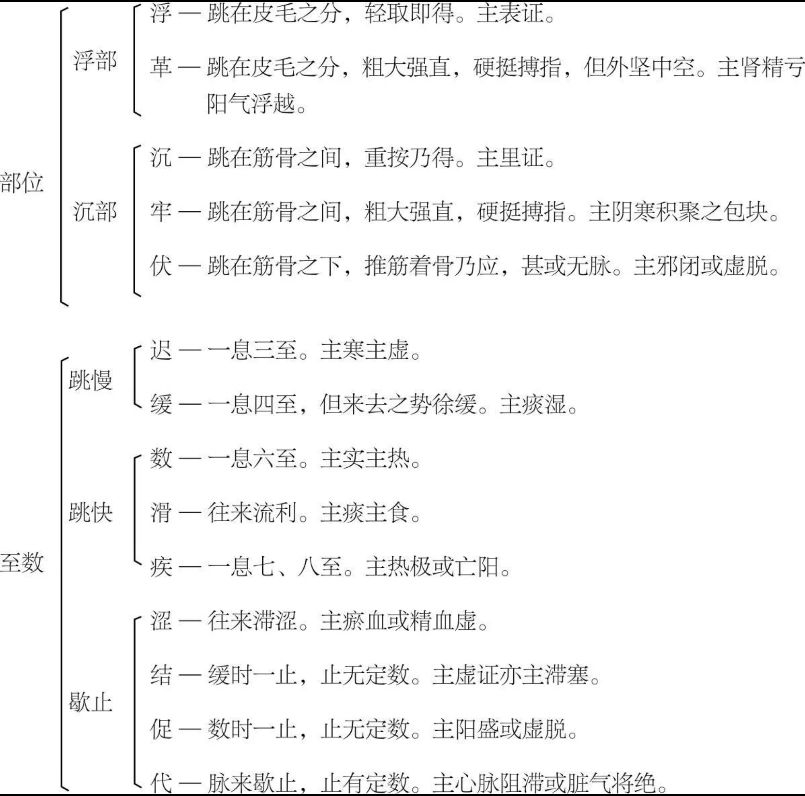

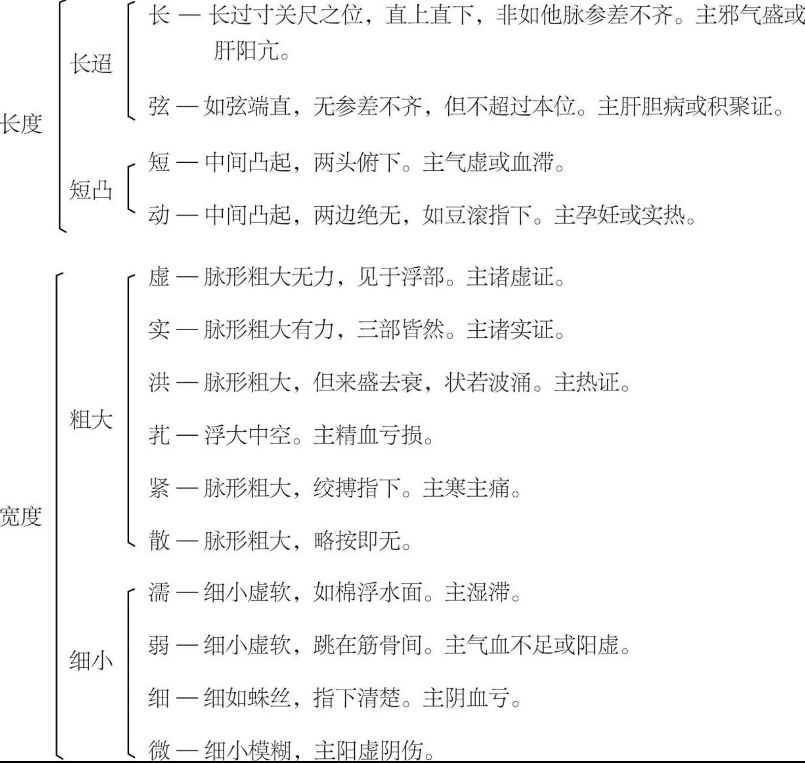

If the pulse loses its stomach, spirit, and root characteristics, it is considered a pathological pulse. There are twenty-eight pathological pulse types, categorized by position, quantity, length, and width. They can be further divided into categories such as pulse jumping between skin and hair, pulse jumping between muscle and bone, pulse shape jumping quickly, pulse shape jumping invasively, pulse shape stopping, pulse shape being long and distant, pulse shape being short and protruding, pulse shape being coarse and large, and pulse shape being fine and small. The list is as follows:

Identification of the twenty-eight pulse patterns and their corresponding diseases

Ancient practitioners proposed many methods for applying the twenty-eight pulses based on the principles of pulse patterns, such as the method of comparison, inference, analogy, and seeking uniqueness, which are described as follows.

1. Method of Comparison (对举法)

The twenty-eight pulses are divided into fourteen pairs to compare and assess their diseases. Superficial and deep, one rises and one falls; superficial indicates rising, deep indicates falling. Slow and rapid, one is slow and one is urgent; slow indicates slow and rapid indicates urgent. Empty and full, one is hard and one is soft; empty is soft, full is hard. Long and short, one is full and one is retracted; long is full, short is retracted. Slippery and rough, one is smooth and one is stagnant; slippery is smooth, rough is stagnant. Slow and fast, one is relaxed and one is tense; slow is relaxed, fast is tense. Moving and still, one is out and one is in; moving is out, still is in. Bound and rapid, one is yin and one is yang; bound is yin, rapid is yang. Flooding and thin, one is strong and one is weak; flooding indicates strength, thin indicates weakness. Empty and solid, one is void and one is real; empty is void, solid is real. Stringy and hollow, one is qi and one is blood; stringy indicates qi, hollow indicates blood. Soft and tight, one is soft and one is hard; soft is soft, tight is hard. Intermittent and scattered, one is long and one is short; intermittent indicates a long-term disease, scattered indicates an acute disease. Large and small, one is strong and one is weak; large indicates strong body, small indicates weak body.

2. Method of Inference (推断法)

Qing Dynasty physician Ke Yunbo proposed six methods of inference for pulse diagnosis, including direct observation, comparative observation, mutual observation, reverse observation, flat observation, and comprehensive observation, which are described as follows. Direct observation — for example, yang pulses indicate yang diseases, and yin pulses indicate yin diseases. Comparative observation — if there is a superficial pulse, there must be a deep pulse; if yang is strong, yin must be weak. Mutual observation — if a yang disease shows a yin pulse, it indicates a loss of yang; if a yin disease shows a yang pulse, it indicates a loss of yin. Reverse observation — if a yang pulse is seen first, followed by a yin pulse, it indicates the progression of disease; if a yin pulse is seen first, followed by a yang pulse, it indicates the retreat of disease. Flat observation — if a yang pulse is accompanied by another yang pulse, it is pure yang; if a yin pulse is accompanied by another yin pulse, it is pure yin. Comprehensive observation — if the pulse remains unchanged while the body shifts from strong to weak, it indicates disease progression; conversely, if it shifts from weak to strong, it indicates recovery.

3. Method of Analogy (比类法)

Pulse patterns are often compared with seasonal changes, six excesses, and seven emotions.

For example, seasonal comparisons: spring corresponds to the liver and has a stringy pulse; summer corresponds to the heart and has a flooding pulse; late summer corresponds to the spleen and has a slow pulse; autumn corresponds to the lungs and has a superficial pulse; winter corresponds to the kidneys and has a deep pulse. Comparisons with the six excesses: superficial corresponds to wind, tight corresponds to cold, flooding corresponds to heat, slippery corresponds to dampness, rough corresponds to dryness, and rapid corresponds to fire. Comparisons with the seven emotions: joy corresponds to a slow pulse, anger corresponds to a stringy pulse, sadness corresponds to a short pulse, worry corresponds to a rough pulse, thought corresponds to a deep pulse, fright corresponds to a moving pulse, and fear corresponds to a rapid pulse.

4. Method of Seeking Uniqueness (求独法)

Seeking uniqueness in pulse patterns involves using the principles of pulse patterns to analyze the unique manifestations of the pulse to assess the disease.

From the unique perspective of pulse patterns, there are distinctions such as unique large, unique small, unique slow, and unique rapid; from the perspective of organs and seasons, for example, the heart should have a flooding pulse but shows a superficial pulse, summer should have a flooding pulse but shows a deep pulse, late summer should have a slow pulse but shows a stringy pulse, autumn should have a superficial pulse but shows a flooding pulse, winter should have a deep pulse but shows a slow pulse, indicating a disease of organ qi conflict. Additionally, from the perspective of position, if all positions are harmonious but one shows a unique pulse, it indicates a change in that area.

The “Jingyue Quanshu” states: “Unique means that all other areas are fine, but this one is slightly off, indicating hidden issues in that area.”

(2) Palpation

Palpation includes examining the hands and feet (including the diagnosis of the skin at the chi), examining the muscle surface, and examining the chest and abdomen. Palpation can assist in discovering various diseases and should be emphasized.

1. Examining the Hands and Feet

Examining the hands and feet actually includes all four examinations, as the limbs are the foundation of all yang and are the main area of the spleen and stomach. Therefore, examining the coldness or warmth of the limbs can indicate the existence or absence of yang qi and the prosperity or decline of the spleen and stomach. Cold hands and feet indicate that a new illness is due to excessive cold evil, while chronic illness indicates spleen yang deficiency; warm hands and feet indicate that a new illness is due to internal heat, while chronic illness indicates heat in the spleen channel. If the back of the hand is warmer than the palm, it indicates an external pathogen; if the palm is warmer than the back of the hand, it indicates internal injury. Cold hands and warm feet, along with excessive sweating and incoherent speech, indicate phlegm-heat obstructing internally; warm hands and cold feet often indicate internal damp-heat. Furthermore, examining the chi skin, the chi skin refers to the section of skin from the transverse crease of the palm to the elbow. If the chi skin is smooth, it often indicates wind evil; if it is rough, it often indicates blood stasis; if it is cold, it indicates yang deficiency; if it is hot, it indicates excess heat.

2. Examining the Muscle Surface

Examining the muscle surface involves palpating the entire skin for temperature, moisture, dryness, and swelling to diagnose changes in diseases. For example, if the body is hot, it indicates excessive evil; if the body is cold, it indicates declining yang qi. If the skin feels very hot upon initial touch but does not remain hot after prolonged pressure, it indicates that the evil is on the surface; if the skin does not feel hot upon initial touch but becomes very hot after prolonged pressure, it indicates that the evil is internal. If the muscle surface is moist, it often indicates sweating; if it is dry, it often indicates a lack of sweating. If the skin is uneven, it indicates internal blood stasis. If there is swelling that rises with pressure, it indicates skin swelling; if it remains depressed after pressure, it indicates edema.

3. Examining the Chest and Abdomen

Examining the chest and abdomen can directly reveal the changes in the organs. If the left side of the chest under the nipple has a rapid pulse, it indicates injury to the zongqi (宗气); if it has a slow pulse, it indicates obstruction of the heart vessels. If the area below the heart and stomach is hard and painful, it indicates a mass in the chest; if it is soft and painless, it indicates qi stagnation.

If the abdomen is full and painful upon pressure, it indicates excess; if it is not painful, it indicates deficiency. If the abdomen feels very hot, it indicates internal heat; if it feels cold, it indicates internal cold. If the right lower abdomen is extremely painful, it often indicates intestinal abscess; if the left lower abdomen has multiple lumps, it often indicates dry stool. If there is a mass under the left rib that is as large as a cup, it indicates liver accumulation, known as “fat qi”; if there is a mass under the right rib, it indicates lung accumulation, known as “xibin”; if there is a mass above the navel that is as large as an arm, extending to below the heart, it indicates heart accumulation, known as “fuliang”; if there is a mass in the stomach area that is as large as a plate, with hunger and fullness, it indicates spleen accumulation, known as “piqi”; if there is a mass in the lower abdomen that pushes up to the chest, it indicates kidney accumulation, known as “bentun”. If the pulse under the fingers feels like a worm moving or has a fluctuating rise and fall after prolonged pressure, or if there is a hard object like a tendon that shifts after prolonged pressure, it indicates parasitic accumulation.

Promoting Traditional Chinese Medicine∣ Sharing Healthy Living Daily

Follow us to learn from renowned physicians

Everyone can become their own doctor