“The relationship between the lung and large intestine” is a concept derived from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) theory, which has played an important guiding role in TCM clinical practice and research, although its scientific basis still requires further validation. Recent popular studies on gut microbiota have re-examined the connection between the “lung and large intestine” from the perspective of microorganisms and human metabolism, providing an important opportunity to deepen the understanding of their relationship.

1 Doubts in TCM Understanding of the Lung and Large Intestine Relationship

The theory of meridians is an important component of traditional Chinese medicine that describes the functional connections between the organs. One of the main functions of the meridians is to connect the organs, and the related theory of “the lung and large intestine being interrelated” first appeared in the Qin and Han dynasties, developed during the Jin, Sui, and Tang dynasties, and matured during the Song, Jin, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. The lung and large intestine are interconnected in terms of fluid metabolism, food transport, and moisture regulation, and the maintenance of digestive function in the human body relies on the coordinated and orderly rise and fall of their qi. The lung is anatomically positioned highest among the organs, referred to as the “canopy,” while the large intestine is positioned lowest among the six fu organs. They occupy the upper and lower ends of the body, respectively, and both are connected to the external environment. The lung, located above, governs the dispersal and descending of qi, expelling the old and taking in the new; the large intestine, located below, is responsible for transportation and the elimination of waste. The two complement each other in the rise and fall of qi in the body. This is a direct explanation of the relationship between the lung and large intestine in organ theory. Ancient and modern physicians have conducted extensive successful clinical practices based on this principle, and the meridian theory serves as the foundation for the relationship between the lung and large intestine. Numerous discussions on the intermediary structures of the interrelationship between the lung and large intestine can be found in ancient texts, especially in the “Huangdi Neijing” (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon). However, with the establishment of the later “organ-centered” TCM theoretical system, the influence of body tissues, acupoints, and other factors outside the organs on the interrelation of organs and meridians has often been overlooked. The doubts in understanding the relationship between the lung and large intestine through meridian theory include: (1) How do the meridians, which lack a recognized material basis, connect the lung and intestine? (2) How can the relationship between the lung and large intestine explain the emotional triggers of lung and intestinal diseases? (3) What insights does gut microbiota research provide for TCM?

2 Microbiota as One of the Material Bases for the Lung-Intestine Connection

2.1 Anatomical Homogeneity: Lung-Intestine Axis and Mucosal Immune Response From an anatomical perspective, chronic gastrointestinal diseases often coincide with chronic lung diseases. The physiological balance of the intestine relies on the coordination of microbiota, and the microbiota in the respiratory tract also regulates lung immune function. Individuals with positive serology for Helicobacter pylori, especially those positive for the cytotoxin-associated gene A, have a lower incidence of asthma and allergic diseases. The increased incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other chronic bronchial diseases is positively correlated with H. pylori infection. The gut-lung axis theory suggests that a healthy gut microbiota is beneficial for lung health. Sepsis is a major cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and numerous studies have demonstrated that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota plays a key role in the pathogenesis of sepsis. The inflammatory response in the alveoli is associated with changes in the lung microbiota (from dominance of gamma-proteobacteria and firmicutes to dominance of Bacteroidetes), and alveolar TNF-α is an important intermediate substance regulating lung microbiota homeostasis. In the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, the content of gut-specific bacteria, which is strongly related to the intensity of systemic inflammation, is significantly higher, indicating that in mouse models of sepsis and patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, the lung microbiota is enriched by gut bacteria. Perhaps the primary source of the lung microbiota after sepsis is the lower digestive tract rather than the upper respiratory tract, suggesting that gut microbiota serves as a bridge connecting the lung and intestine.

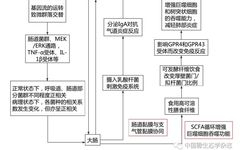

2.2 Shared Physiological and Pathological Basis of the Lung and Large Intestine Clinical data supports that patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) often have concurrent lung diseases. Yazar first pointed out that about one-third of IBS patients have respiratory diseases such as asthma, suggesting that this correlation may be related to hypothalamic dysfunction in IBS patients. Patients with COPD are more likely to develop ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and asthma shares the same physiological and pathological basis as IBS, involving various possible mechanisms including the nervous system, immune system, and smooth muscle regulation. Recent studies have further revealed the close relationship between the lung and large intestine from the perspective of gut microbiota (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Understanding the Close Relationship Between the Lung and Large Intestine from the Perspective of Gut Microbiota

2.3 Is Microbiota One of the Material Bases for Meridian Theory? The “Lingshu” states: “The hand Taiyin lung meridian originates in the middle jiao, connects to the large intestine, and returns to the stomach…” and “The large intestine hand Yangming meridian… descends into the diaphragm, connects to the lung, and belongs to the large intestine.” It can be seen that the meridian connection is the foundation of the relationship between the lung and large intestine. However, the meridians, as a “foundation,” lack a recognized anatomical structure. Is the gut microbiota one of the material bases for the meridians? Perhaps this is a form of modern medicine’s “empiricism”? In fact, this so-called empiricism is not based on the absolute value of visible discoveries, nor is it based on the resolute rejection of various systems and their fantasies, but rather on the reorganization of obvious and hidden spaces. The understanding of the relationship between the lung and large intestine through meridian theory may be validated by modern medical research on gut microbiota, reflecting a developmental trend of “holistic thinking” in the restructuring of modern medical knowledge. The “meridian lines” described by ancient people are not about the lines themselves but about their role in “illustrating connections.” The TCM concept of “the lung and large intestine” should not only concern anatomical structures but should focus more on functions. This functional connection is reflected in modern medical research on the lung-intestine axis, and meridian theory is not merely about the superficial pathways of meridians but is more importantly about explaining the connections between organs. Modern medicine has often viewed organs in isolation, while microbiota theory connects the lung and large intestine, embodying the idea of connection in meridian theory in modern medicine.

3 The Gut Microbiota Basis for the Lung’s Emotion of Sadness (Worry)

Emotional disorders are one of the triggers for IBS, with 50% to 90% of IBS patients experiencing anxiety, depression, and other psychological disorders. Depression is primarily characterized by sadness and loss of interest, and sadness and worry are governed by the lung among the five organs.

The “Zhi Zhen Yao Da Lun” states: “Thunder in the bowels, qi surges up to the chest, causing wheezing and inability to stand for long, indicating that the evil resides in the large intestine.” When the large intestine is diseased, the rise and fall of qi is disrupted, surging up to the chest and obstructing lung qi, leading to pulmonary symptoms. The lung corresponds to the emotion of worry, thus patients with intestinal diseases may exhibit emotional distress and worry. Merely explaining the viewpoint of “the lung governs sadness (worry)” through meridian connections or the shared metal element of the lung and large intestine seems to lack material evidence.

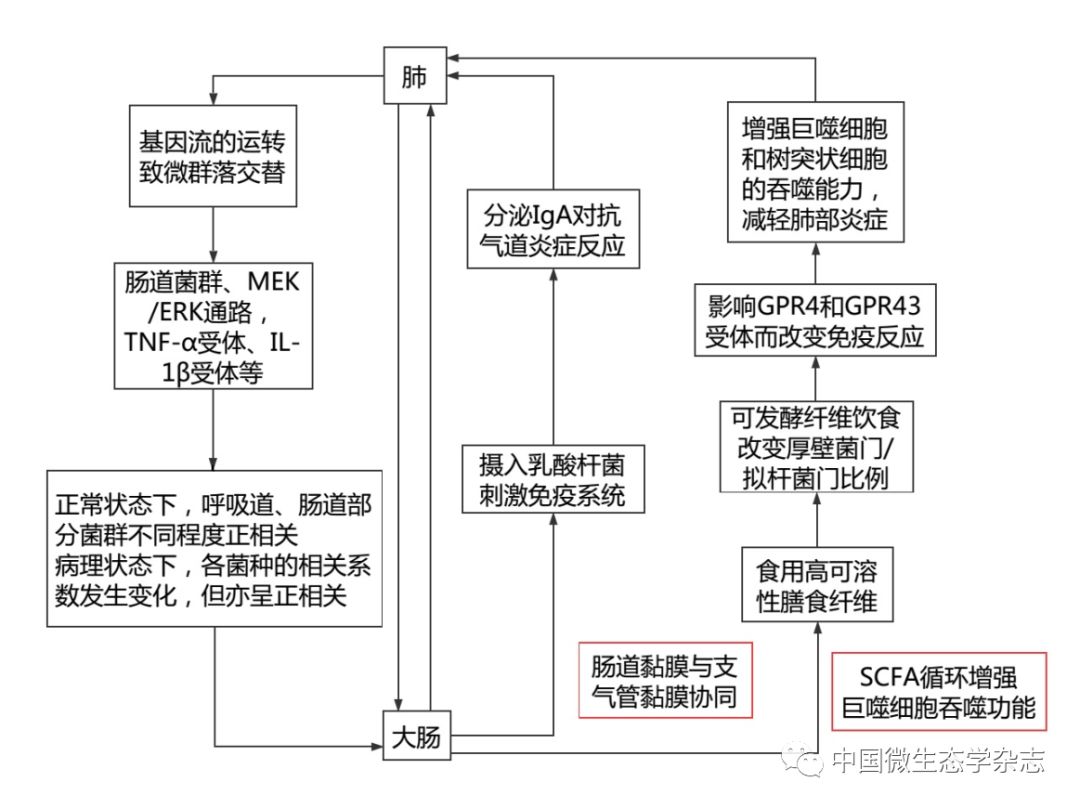

Gut microbiota can regulate cognitive development and behavioral activities, and it has been confirmed to be closely related to various neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and anxiety disorders. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is one of the mechanisms underlying depression and may also be used to explain the viewpoint of “the lung governs sadness (worry).” 5-HT is an important antidepressant substance, with approximately 90% of 5-HT synthesized and distributed in gut enterochromaffin cells, and the gut microbiota-mediated release of 5-HT plays a key role in the onset and development of depressive symptoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Understanding the Material Basis for the Lung’s Emotion of Sadness from the Perspective of Gut Microbiota

It is worth noting that with advancements in sampling methods and analytical techniques, the individual differences in gut microbiota have been further described. Studies have revealed changes in gut microbiota structure due to gender differences in the BTBR mouse model of autism. Although the specific changes in gut microbiota species in patients with depression have not been consistent, various literature reports have reached the same conclusion that specific changes in microbiota can lead to depression and anxiety.

In TCM, diseases related to emotions are often attributed to the heart, brain, and other organs, while the viewpoint of “the lung governs sadness (worry)” relies heavily on the five-element theory and can be validated through principles such as “seeking the same qi.” The close relationship between gut microbiota and depressive symptoms, as shown in Figure 2, may serve as the material basis for explaining “the lung and large intestine being interrelated” in the context of “the lung governs sadness (worry).” The lung and large intestine share similar physiological and pathological foundations, and gut microbiota, as one of the direct regulators of emotions, plays a dominant role in the brain-gut axis. The close relationship between gut microbiota and depression can be further explained through the lung-intestine axis, demonstrating the convergence of Eastern and Western medical thinking.

4 Insights from Gut Microbiota Research for TCM

“The lung and large intestine being interrelated” is one of the foundational theories of TCM derived from the “Lingshu: Ben Shu” which states, “The lung connects to the large intestine, and the large intestine is the repository of transportation.” The “Lingshu: Jingmai” also points out, “The lung hand Taiyin meridian originates in the middle jiao, connects to the large intestine, and returns to the stomach.” The meridian can be seen as a carrier through which ancient people used simple observations to summarize the connections between organs, indicating that “meridians” are a theoretical term.

The “Zhen Jiu Wen Dui” states: “The sage’s use of needles relies on the meridian points; without the meridian points, students cannot receive instruction. If students do not understand the flexibility of the meridian points, merely adhering to the points is like searching for a horse by following a map; how can one fully grasp the method?” This indicates that “meridian points” are a set of theoretical terms that aid memory. Theoretical terms are more like mnemonic devices, acronyms, or symbols without actual significance or literal meaning, serving as tools. The goal of science is to improve the reliability of these tools, rather than worrying about whether they correspond to the literal interpretation of these tools. The description of “meridian lines” itself cannot find material reality, but meridian theory provides a relatively reliable approach to understanding the connections between different parts of the body, especially the connections between organs, just as it was used to explain the relationship between the lung and large intestine. The research on gut microbiota provides a clearer material basis for the organ connections suggested by meridian theory at the molecular level. Thus, we can conclude that the universal laws unique to biology still need to be discovered and validated at the molecular biology level. The biological models we express may work for us, who have computational limitations, but those models do not practically reflect the real laws of operation at certain levels of organic tissue and its populations. TCM scholars should adopt a more inclusive attitude towards research like that of gut microbiota, absorbing the achievements of modern civilization to develop TCM.