Low back pain is the second most common clinical condition after the common cold, but it involves numerous factors, making diagnosis difficult. Detailed history taking and physical examination play a crucial role in diagnosing low back pain. Recently, I revisited the history taking and physical examination for low back pain and compiled this information to share with everyone.

Low Back Pain

Inquiry: 1. Location of Pain

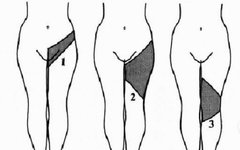

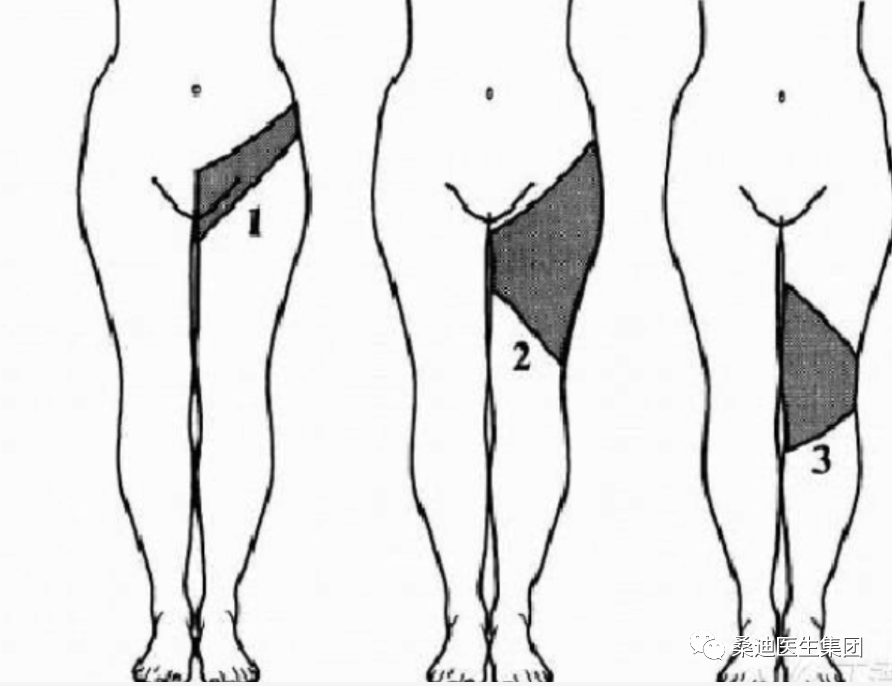

It is significant for patients to point out the location of their pain, as their understanding of anatomy is often superficial. Many patients believe that the area from below the neck to above the buttocks is the low back. Some patients may indicate shoulder blade areas when describing back pain. The way patients describe the location of pain can also be important for diagnosis. Emotionally stable patients often move their palms back and forth over the most prominent area of pain to describe the radiating path of the pain. In contrast, patients with feigned illness or emotional instability often point to the area of pain with their thumbs without touching the painful region. Radiation to the legs is an important symptom. Referred pain rarely involves the knee joint and generally indicates nerve root pain, which usually extends below the knee joint. The following image shows the localization of responsible nerve roots (L1 to S1).

The relationship between leg pain and low back pain generally indicates that nerve root pain in the legs is greater than that in the low back.

Inquiry: 2. Impact of Activity on Pain

We should ask the patient the following questions in detail:

1. Does it hurt when you stand up?

2. Does it hurt when you bend over?

3. Does it hurt when you get up or turn around?

4. Does it hurt when you rest?

5. Does it hurt when you go up and down stairs?

6. Does it hurt when you stand or sit for a long time?

7. What do you do when the pain worsens? Do you lie down, stop, sit, or move around?

These questions are significant for our diagnosis. Generally, mechanical pain worsens with activity and alleviates with rest, such as discogenic pain. Pain from small joints often worsens when getting up in the morning, suddenly turning, or bending over. In contrast, visceral referred pain does not worsen with activity and does not alleviate with rest, such as in cases of duodenal ulcers. Accumulated nerve root neuromas often require continuous movement to alleviate pain. Tumor-related pain is generally not related to activity and is more commonly seen as resting pain or night pain.

Inquiry 3: Duration and Progression of Pain.

We may need to ask the following in detail: When did the pain start? How did the pain begin? Was there any trauma before the onset of pain? Are there any other triggers for the pain? Is the pain gradually worsening or sudden? Is the pain continuous or intermittent? Is there any visible pattern to the pain? Is the pain becoming more severe, including frequency of attacks, intensity of pain, and duration? For example, severe paroxysmal pain after intense activity is often caused by mechanical factors. In contrast, severe pain after minor activity should raise suspicion of pathological fractures, such as compression fractures in osteoporotic patients who lift heavy objects. For individuals over 60, the possibility of tumors should not be overlooked.

Inquiry 4: Degree of Functional Limitation

The degree of symptoms and functional limitations can help us distinguish whether the patient’s disability is mild, moderate, or severe. A clear classification aids in formulating an appropriate treatment plan.

If the patient has bowel or bladder incontinence, it is likely that there is cauda equina compression, which is a clinical emergency requiring immediate surgical intervention to relieve the pressure; conservative treatment is not an option. If a cervical spondylosis patient experiences leg weakness or a sensation of walking on cotton, it indicates severe spinal cord compression, and general minimally invasive procedures may be ineffective, often requiring decompression surgery.

Inquiry 5: Accompanying Symptoms

1. Low back pain with spinal deformity; deformity after trauma is often due to spinal fractures or dislocations; congenital deformities are often due to congenital spinal diseases.

2. Low back pain with limited activity is seen in spinal injuries, ankylosing spondylitis, and acute soft tissue sprains in the low back.

3. Low back pain with prolonged low fever is seen in spinal tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis; high fever is seen in suppurative spinal inflammation and paravertebral abscess.

4. Low back pain with urinary frequency, urgency, or incomplete urination is seen in urinary tract infections, prostatitis, or prostatic hyperplasia; severe low back pain with hematuria is seen in kidney or ureteral stones.

5. Low back pain with belching, acid reflux, and upper abdominal bloating is seen in gastric or duodenal ulcers or pancreatic diseases; low back pain with diarrhea or constipation is seen in ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

6. Low back pain with menstrual irregularities, dysmenorrhea, or excessive leukorrhea is seen in cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or ovarian and adnexal inflammation or tumors.

Inquiry 6: Previous Examinations and Treatments

We should learn to analyze and dialectically view previous examinations and treatments. For patients who have undergone formal treatments, there is no need to repeat them; however, it is necessary to revisit informal treatments. The effects of formal treatments can also help us differentiate diseases effectively.

Physical Examination 1: Observation of Gait. Observe the patient’s walking. Is there a gait that avoids pain, such as a hip or knee pain gait? Is there a gait indicating nerve damage, such as rigidity or spasm? Is there a shopping cart position indicating spinal canal stenosis? Is there a limp after prolonged walking?

Spinal Shape. Observe from the back and side for any deformities.

Skin Markers: Skin pigmentation spots are indicative of neurofibromas. Lipomas or hypertrichosis in the lumbar region may suggest deep bony deformities such as occult spinal dysraphism with or without neurogenic tumors (tethered cord syndrome).

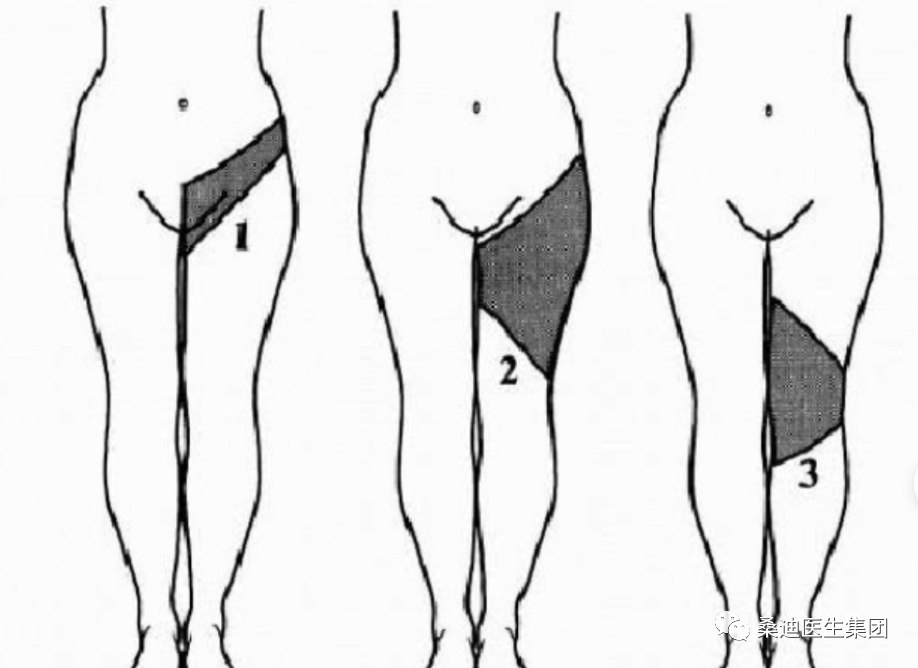

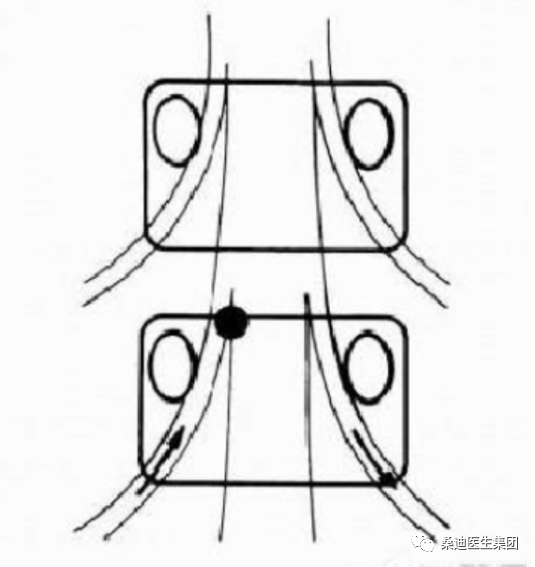

Range of Motion and Rhythm. Observe the range of forward bending, backward extension, lateral bending, and rotation, and pay attention to the rhythm. Through these tests, observe for specific deformities, such as: in cases of lumbar stiffness, forward bending is significantly limited, commonly seen in root pain caused by intervertebral disc herniation. Such patients often bend towards the side of pain during forward bending. Total spinal stiffness is a characteristic feature of late-stage ankylosing spondylitis. Abnormal rhythm during forward bending and standing is characteristic of small joint injuries (see image).

Muscle Strength Examination. Repeatedly perform toe raises and heel raises (fatigue test); normally, one should be able to perform more than 10 toe raises quickly. If fewer than 10, it may indicate early lesions. Abnormal heel raises suggest L5 nerve root compression, while abnormal toe raises suggest S1 nerve root compression. If toe raises cause knee flexion, it indicates quadriceps weakness, possibly due to femoral nerve irritation.

Physical Examination 2: Reflexes

Knee reflex enhancement is commonly seen in pyramidal tract damage; knee reflex hyperactivity may accompany patellar clonus. Diminished knee reflex suggests damage to the femoral nerve (L2-L4).

Ankle reflex abnormalities suggest damage to the sciatic nerve (S1). It is important to note that tendon reflexes are significantly influenced by consciousness; if necessary, reinforcement experiments can be conducted. The method is as follows: have the patient interlock their fingers and perform muscle strength tests. Repeatedly perform toe raises and heel raises (fatigue test); normally, one should be able to perform more than 10 toe raises quickly. If fewer than 10, it may indicate early lesions. Abnormal heel raises suggest L5 nerve root compression, while abnormal toe raises suggest S1 nerve root compression. If toe raises cause knee flexion, it indicates quadriceps weakness, possibly due to femoral nerve irritation.

Physical Examination 2: Reflexes. Knee reflex enhancement is commonly seen in pyramidal tract damage; knee reflex hyperactivity may accompany patellar clonus. Diminished knee reflex suggests damage to the femoral nerve (L2-L4).

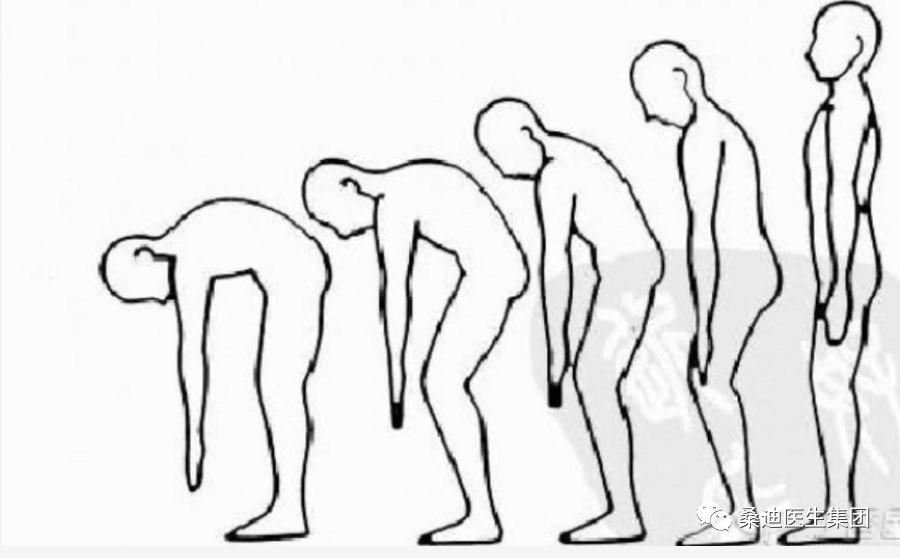

Ankle reflex abnormalities suggest damage to the sciatic nerve (S1). It is important to note that tendon reflexes are significantly influenced by consciousness; if necessary, reinforcement experiments can be conducted. The method is as follows: have the patient interlock their fingers and apply outward force; at this time, the examiner’s tapping of the tendon reflex will be higher than usual (see image).

Physical Examination 3: Pathological Signs.

1. Babinski’s sign: The examinee lies supine with legs extended; the doctor holds the examinee’s ankle and uses a blunt-ended stick to stroke the outer edge of the foot from back to front to the little toe, causing the big toe to extend and the other toes to fan out.

2. Chaddock’s sign: Stroke the outer edge of the foot from back to front below the outer ankle.

3. Oppenheim’s sign: The doctor applies pressure with the thumb and index finger along the anterior border of the tibia from top to bottom.

4. Gordon’s sign: The examiner squeezes the gastrocnemius muscle with a certain force.

Positive pathological signs mainly indicate damage to the pyramidal tract, but it should be noted that infants may show normal positive signs; additionally, patients who are under general anesthesia or in a hypoglycemic coma may also exhibit these signs.

Physical Examination 4: Muscle Strength Examination.

The first sign of L5 nerve damage is weakness of the extensor hallucis longus muscle, while the first sign of S1 nerve damage is weakness of the flexor hallucis longus muscle. It is important to note that patients with root pain may exhibit false positives during these resistance muscle strength tests due to increased pain, so the examination should be performed with the knees and hips flexed.

Related Diseases: • Sensory Abnormalities

Physical Examination 5: Sensory Abnormalities Examination

Sensory assessment is a delicate technique. During the examination, pay attention to the following points:

1: Ensure that the examination needle is clean and not the same needle that has punctured a previous patient.

2: Avoid any suggestive questions, such as “Is it more painful on this side?”

3: Note the comparison of the same position on both sides.

4: For questionable areas, more precise examination methods can be used. Continuous needle pricking at the same location 10 times; areas with sensory nerve damage often only feel 1 to 2 times.

Related Diseases: • Low Back Pain

Physical Examination 6: Nerve Root Signs. The straight leg raise test: Although it seems simple, there are many details to pay attention to. The examination steps are as follows: The patient lies supine and relaxed; the examiner raises the patient’s leg while keeping the other hand on the knee to maintain the leg straight. When pain occurs in the leg or buttock, note the pain; at this time, ankle dorsiflexion pain worsens (further confirming it is root pain), and then flexing the knee alleviates the pain (further confirming it is root pain).

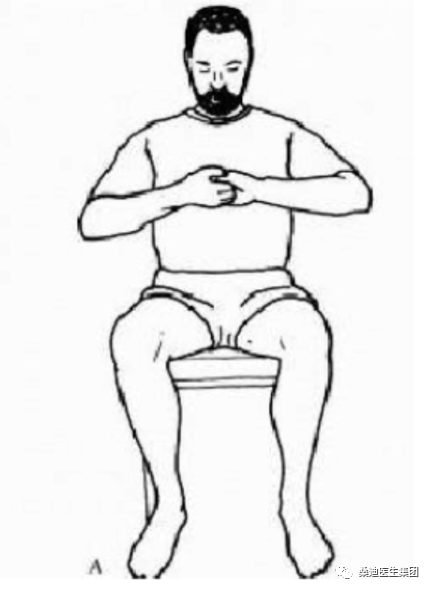

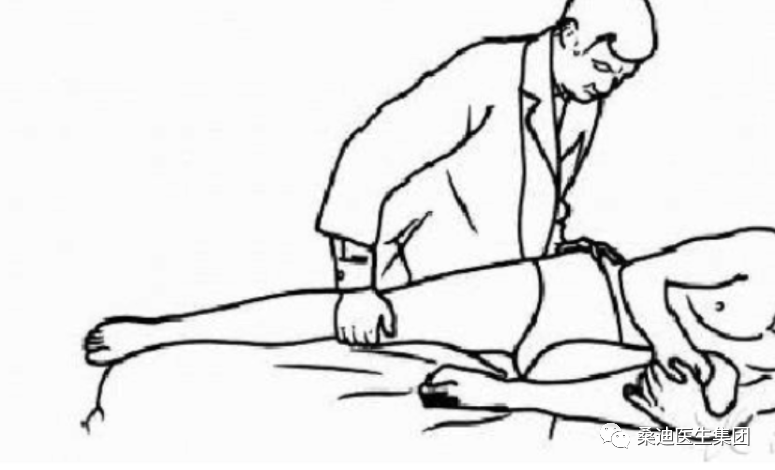

The significance of the straight leg raise test on the healthy side: It suggests that the protrusion is located at the axilla or inside the nerve root (see image).

Supine abdominal lift test: For some dancers, acrobats, or athletes, due to prolonged training, the joint ligaments may be very lax. When the straight leg is raised to 90°, it can be used for differentiation. The method is as follows: The patient lies supine with both legs extended, using the head and both heels as support, lifting the abdomen off the bed. If low back pain is felt and while maintaining this position, deep breathing for 30 seconds until the face turns red, or if pain radiates to the affected limb, it is positive; or if pain occurs when coughing while maintaining the abdominal lift, it is also a positive sign. This test can also be performed by compressing the patient’s neck veins or pressing on the patient’s abdomen; if pain occurs in the affected limb, it is still a positive sign. This test is significant. The bowstring sign: This may be the most reliable nerve root traction test. The method is as follows: generally, after performing the straight leg raise test, if knee flexion reduces pain, the patient’s lower limb is pressed against the affected side.

Root pain patients will experience radiating pain to the lower limb (see image). If pressing the hamstring also causes pain, it suggests the patient may have psychological factors.

All of the above are tests for sciatic nerve traction. For root symptoms above L4, a femoral nerve traction test should be performed. There are two methods for the femoral nerve traction test: one is for the patient to lie prone with the affected knee joint extended; the examiner raises the affected lower leg, placing the hip joint in hyperextension, with the limb extended. The examiner stands beside the patient, holding the patient’s ankle on the affected side, flexing the knee joint to bring the heel as close to the buttock as possible. Pain in the anterior thigh indicates a positive sign. The principle of this test is that it stretches the psoas major and quadriceps muscles, causing tension in the upper lumbar nerve roots, resulting in pain (this test is also called the heel-buttock test).

Physical Examination 7: Joint Examination “4” Sign Test

Operational Method: The patient lies supine with one lower limb extended and the other lower limb placed in a “4” shape near the knee joint of the extended limb. One hand presses down on the knee joint while the other hand presses down on the opposite iliac crest. Both hands apply downward pressure simultaneously. If pain occurs in the sacroiliac joint during the downward pressure, or if the flexed knee joint cannot touch the bed, it is positive. Note the comparison of both sides. A positive sign suggests sacroiliac joint or hip joint lesions.

Resistance to external abduction test of both lower limbs: The patient lies on their side, and the lower limb is tested for resistance to external abduction. During the examination, strong contraction of the gluteal muscles separates the sacrum from the pelvis. Patients with sacroiliac joint lesions will experience pain.

Hip joint hyperextension test: The healthy hip joint is flexed, and the thigh is pressed tightly against the chest, causing tension in the lumbar spine. When the upper hip joint is excessively extended, the sacroiliac joint rotates excessively, and patients with sacroiliac joint lesions will experience pain (see image).

Physical Examination 8: Direct Tenderness of Spinous Processes. The detail is: during the examination, do not apply vertical pressure; instead, apply a downward and lateral force to the spinous process to induce rotation in the affected segment. If pain can be reproduced, it is significant.

Low Back Pain Inquiry

1. How long has the pain lasted? Including the initial onset of pain and the duration of this episode.

2. What caused the pain? The causes of pain can be classified into acceleration and deceleration types. Deceleration is associated with a history of sprain, where severe pain suddenly occurs due to a known cause, alleviating after rest or treatment, leaving chronic pain that fluctuates in intensity and recurs. Acceleration occurs without a clear injury history, gradually worsening due to chronic strain, ultimately leading to severe pain.

3. Pain intensity. ① If 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst pain, what number represents the current pain level? ② Pain is unbearable and severely affects work and life. Pain is tolerable but particularly distressing, severely affecting work and life. Pain exists but is not particularly distressing, affecting work but not life. Pain exists but does not affect work or life.

4. Is the pain continuous or intermittent? Is the pain the same throughout the day or does it worsen intermittently? When is the pain most severe: morning, afternoon, evening, or night? How long does each episode of pain last? Does the pain alleviate on its own or with any methods? What factors influence the worsening or alleviation of pain?

5. From the onset until now, has the pain gradually worsened, lessened, or remained the same?

6. Is there any relationship between pain and weather changes?

7. Does the pain lessen or worsen with activity? Is there any limitation in activity?

8. How does the pain differ in sitting, standing, walking, or lying down?

9. Does it hurt when changing positions from standing to sitting? Or does it hurt after sitting for a long time? Or does it hurt when standing up from a sitting position, alleviating after activity?

10. Is it difficult to stand up straight after sitting for a long time, requiring some movement to straighten the back? Or is it difficult to bend for a long time?

11. Can you stand still without pain? Does it cause pain?

12. Is there any pain while walking? Does it worsen with distance, or does it lessen after walking for a while? Can you walk long distances?

13. Is there pain when first falling asleep, or does it occur later in the night? Is it comfortable to sleep on your back, stomach, or either side? Does the pain affect sleep? After sleeping for a long time, is the pain unbearable, requiring you to get up and move to alleviate it?

14. After a night’s sleep, is the pain worse or better in the morning?

15. Does the pain worsen or alleviate when at rest?

16. Is there a history of low back pain? What examinations have been done, and what were the results? What treatments have been undertaken? What were the effects?

17. Have there been any examinations or treatments after this episode? What were the results?

18. Where is the pain located? ① The 12th thoracic vertebra and the 1st and 2nd lumbar vertebrae belong to upper lumbar pain. ② The 3rd and 4th lumbar vertebrae belong to middle lumbar pain, while the 5th lumbar vertebra and sacrum belong to lower lumbar pain. ③ Pain on both sides of the lumbar transverse processes. ④ Pain on both sides of the sacrum. ⑤ There may be significant pain below the rib arch and above the iliac crest.

19. Examinations can be divided into tenderness and percussion pain. Press along the midline of the back and both sides, sequentially pressing the lumbar and sacral spinous processes, interspinous spaces, both sides of the lamina, articular processes, transverse processes, lower rib margins, upper iliac crest, and sacroiliac joints to identify positive reaction points.

20. The lumbar region can be divided into central lumbar pain (upper, middle, and lower segments), and lateral pain (divided into pain at the transverse processes, rib arch, iliac crest, and sacroiliac joint).

21. The lumbar region may also be accompanied by radiating pain to the lower limbs, with pain radiating to the hip, knee, ankle, and foot. Pain to the hip can be divided into anterior-lateral pain below the anterior superior iliac spine, middle pain in the gluteus medius, and posterior pain in the gluteus maximus, piriformis, and sciatic nerve. The lower limb can be further divided into anterior, posterior, medial, and lateral pain, with numbness and pain in the dorsum and sole of the foot. The numbness of the toes should be inquired about clearly. 22. Is there any history of major diseases such as hypertension, heart disease, or diabetes?

23. Is there any sensation of cold or heat?

24. What is the nature of the pain: aching, stabbing, lightning-like, throbbing, or cutting pain? Is it intermittent or continuous?

25. Is there any numbness? Numbness is a sensation of nerve irritation, a dynamic feeling like electricity or insects crawling, while numbness is a static feeling of swelling. Subjective numbness is when the patient feels numbness but the doctor finds normal superficial sensation, indicating no nerve damage and a mild condition. Objective numbness indicates reduced or absent superficial sensation, objectively existing, indicating varying degrees of nerve damage with clear areas of sensory reduction. All numbness should be inquired about regarding the affected area. Pain is an inflammatory response, while numbness is a manifestation of nerve irritation.

26. Does coughing worsen the pain? Not only can spinal canal lesions worsen with coughing, but also extra-spinal lesions can worsen.

27. Does carrying items or holding children affect low back pain?

28. Is the pain a sensation of discomfort, or is it a feeling of weakness, as if unable to support the body, needing to sit down after standing for a while? Is there a sensation of sharp pain in the low back, making you afraid to move?

29. Pay attention to the overall condition of the body to rule out diseases causing fever, weight loss, etc., such as bone tuberculosis or tumors.

30. Rule out visceral diseases causing referred pain. Pain caused by visceral diseases is generally unrelated to movement and posture, with no obvious tenderness points, diffuse pain, and unclear pain range.

31. Differentiate between nerve trunk, plexus, and root pain. For example, pain from the sciatic nerve trunk may simultaneously have symptoms of the tibial and peroneal nerves but will not have symptoms from other nerve distribution areas. Plexus pain may have symptoms from multiple nerves simultaneously. Root pain generally compresses only one segment of the nerve, with a fixed nerve segment distribution area. The size of the pain and numbness area can help diagnose the site of nerve compression.

32. Differentiate between nerve pain, muscle pain, vascular pain, and joint pain. Nerve pain generally has a wider pain range, with less local tenderness than muscle pain, and the range of motion in the painful area is not significantly limited. Muscle pain generally follows the distribution of muscle origin and insertion, not exceeding the muscle distribution area, and may worsen with movement of the affected muscle. Vascular pain may present with coldness, skin discoloration, and abnormal pulsation, generally unrelated to limb movement. Joint pain is localized around the joint, affecting flexion and extension activities, differing from the linear pain of nerves and the band-like pain of individual muscles; care should be taken to differentiate these during inquiry based on the characteristics of each type of pain.

Physical Examination

1. When standing, can the patient bend forward and touch the ground with their fingertips? Is there pain? Is it that they cannot bend at all, or cannot bend fully, or is there pain while bending? Is there pain when starting to bend, while bending down, or when straightening up after bending?

2. Is there pain when extending the back? Use a finger to point to the painful area.

3. Is there pain when rotating to the left or right? Is it pain on the same side or the opposite side? Use a finger to point to the painful area. Are the angles of rotation on both sides the same? Can both sides rotate fully?

4. Is there pain when bending to the left or right? Is it pain on the same side or the opposite side? Use a finger to point to the painful area. Are the angles of bending on both sides the same? Can both sides bend fully? Do these movements cause radiating pain to the lower limbs? If so, indicate the painful area.

5. When the patient is prone, first check if the curvature of the spine is normal. Is there any increase or decrease? Is there any lateral curvature?

6. Are the iliac crests level? Is there any anterior or posterior pelvic tilt or rotation?

7. Are there any spasms, hypertrophy, atrophy, cord-like structures, or nodules in the muscles?

8. When the patient has tenderness or radiating pain in the lumbar region while in a prone position, place a pillow under the abdomen to flex the lumbar region. If pressing on the painful point does not change the pain, suspect extra-spinal factors; if the pain decreases, suspect intra-spinal factors. Move the pillow from under the abdomen to under the chest, placing the lumbar region in an extended position. If pressing on the painful point increases the pain, suspect intra-spinal lesions.

9. Lateral bending test. The patient stands with arms hanging down; the doctor supports one side of the patient’s hip while the other hand supports the opposite ribcage, applying force towards the midline to make the patient perform a passive lateral bending motion. If radiating pain or numbness occurs in the lower limb, suspect intra-spinal lesions.

10. Supine abdominal lift test. The patient lies supine with legs extended, using the head and heels for support, lifting the abdomen off the bed and holding the breath for half a minute to a minute. If radiating pain or numbness occurs in the lower limbs, suspect intra-spinal lesions.

11. Neck flexion test. The patient lies supine, and the doctor flexes the patient’s head forward for one minute. If radiating pain or numbness occurs in the lower limbs, suspect intra-spinal lesions.

12. Knee-hug test. The patient lies supine, hugging their knees to flex the hip and knee joints as much as possible. If there is pain in the lumbosacral joint, it is positive.

13. Hip-knee flexion test. The patient lies supine, flexing the hip and knee joints. The examiner holds the patient’s knee, flexing the hip and knee joints as much as possible, pushing towards the head, causing the buttocks to lift off the bed. If pain occurs in the lumbosacral joint, it is positive. If performing a unilateral hip-knee flexion test, the patient extends one lower limb, and the examiner flexes the other hip and knee joint in the same manner, pushing towards the head. The lumbosacral and sacroiliac joints will move accordingly; if pain occurs, it is positive. If there is soft tissue injury, strain, or lesions in the lumbar intervertebral joints, lumbosacral joints, or sacroiliac joints, or lumbar tuberculosis, this test may be positive. However, in cases of lumbar disc herniation, this test is often negative.

Low Back Pain Symptoms

1. Cannot bend over 2. Cannot stand straight 3. Cannot sit 4. Cannot stand5. Cannot lie down6. Cannot turn over7. Loss of normal lumbar curvature8. Increased lumbar curvature9. Lateral curvature of the lumbar vertebrae10. Worse in the morning, better in the afternoon11. Better in the morning, worse in the afternoon12. Cannot carry items13. Cannot carry on the back14. Worse on cloudy days15. Pain when squatting16. Pain when squatting or sitting down during the standing process, but no pain after standing up17. Pain when changing from standing to squatting or sitting, but no pain after squatting or sitting18. Difference in pain when sitting on a high stool versus a low stool19. Difference in pain when sitting on a soft seat versus a hard seat20. Feels empty under the lumbar region when lying flat, needing to place something for comfort21. Feels heavy and sagging in the lumbar region, wanting to sit down after standing for a while22. Aching and swelling in the lumbar region

23. Weakness in the lumbar region24. Cold sensation in the lumbar region25. Stiffness and rigidity in the lumbar region26. Sensation of wanting to “throw out” the lumbar region

In clinical practice, patients with low back pain exhibit these symptoms, and we gather all the observations. As long as it is low back pain, these are the symptoms.

We then analyze the causes of each symptom.

Finally, we provide treatment methods. For symptoms such as loss of normal curvature, increased curvature, inability to stand straight, and bending, several treatment methods can resolve these symptoms.

Regardless of the direction—front, back, above, below, proximal, or distal—acupuncture, manipulation, cupping, and exercise can all be used to solve the problem.

Let everyone see the patient and know where to ask. When the patient describes the symptoms, we know where to treat. A precise inquiry leads to effective treatment, which can enhance our skills.

There is no need to learn about difficult diseases; mastering the treatment of common symptoms is sufficient.

If we only discuss muscle function theory, it will not connect when treating diseases, leaving us at a loss.

Patients come for treatment of symptoms, and we provide methods to eliminate symptoms. For example, in classical formulas, there are symptoms and corresponding treatments. By identifying symptoms, we can find treatment methods, whether we understand the mechanism or not. As long as we know where to perform acupuncture or manipulation to eliminate symptoms, that is sufficient. Research is the responsibility of experts and scholars; for us in clinical practice, knowing how to alleviate symptoms is enough. We should focus on one area and develop a treatment model and standards together.