In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the practice of observation, known as wang zhen (望诊), involves the purposeful examination of visible signs and excretions from the body to understand health or disease states.

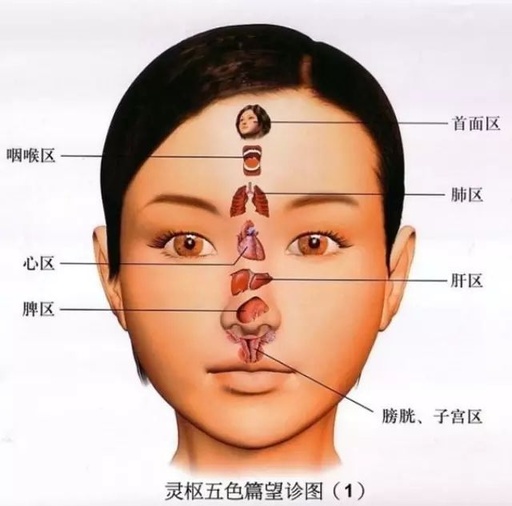

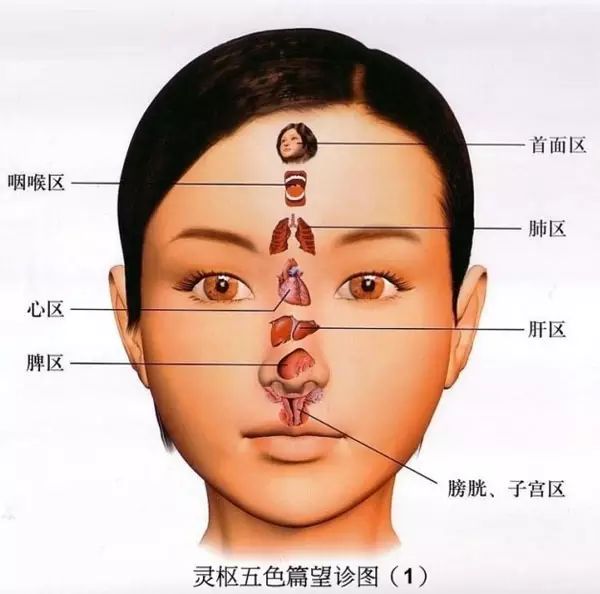

The content of wang zhen primarily includes observing the patient’s spirit, color, shape, posture, tongue appearance, pulse, skin, and the conditions of the five sensory organs, as well as excretions and secretions in terms of their form, color, and quality. Wang zhen can be divided into five categories: comprehensive observation, local observation, tongue observation, excretion observation, and observation of children’s fingerprints. Although tongue diagnosis and facial color diagnosis belong to the five sensory organs, they are particularly valuable as they reflect internal organ changes accurately. Therefore, facial diagnosis and tongue diagnosis are introduced as unique traditional diagnostic methods in TCM.

Comprehensive Observation

Comprehensive observation involves understanding disease conditions through the observation of changes in the overall spirit, color, shape, and posture of the body.

(1) Observing Spirit

Observing spirit refers to the examination of the external manifestations of life activities in the human body, specifically the observation of a person’s mental and functional state.

The term spirit encompasses both broad and narrow definitions: in a broad sense, it refers to the external manifestations of life activities, essentially equating spirit with life; in a narrow sense, it refers to mental activities, equating spirit with consciousness. Observing spirit should include both aspects.

The spirit is a function based on the material foundation of qi (气) and jing (精), which is the external manifestation of the five organs. Observing spirit can reveal the vitality of the five organs and the severity and prognosis of the disease. Key observations should focus on the patient’s mental state, consciousness, facial expressions, physical movements, and responsiveness, particularly the changes in the eyes. The content of observing spirit includes gaining spirit, losing spirit, and false spirit, as well as insufficient spirit and abnormal consciousness.

1. Gaining Spirit

Gaining spirit, also known as having spirit, is a manifestation of abundant qi and jing; in illness, it indicates that the righteous qi is intact, suggesting a mild condition and a good prognosis.

Manifestations of gaining spirit include: clear consciousness, coherent speech, a rosy and moist complexion, natural and rich expressions; bright eyes with inner vitality; quick responses, agile movements, and relaxed posture; steady breathing, and well-toned muscles.

2. Losing Spirit

Losing spirit, also known as having no spirit, indicates a depletion of jing and qi, and a decline in spirit. At this stage, the condition is severe, and the prognosis is poor.

Manifestations of losing spirit include: lethargy, unclear speech, or confusion, wandering aimlessly, or collapsing with closed eyes and open mouth; a dull complexion, apathetic or stiff expressions; dim eyes and a vacant stare; slow responses, impaired movements, and forced postures; weak or labored breathing; and significant muscle atrophy.

3. False Spirit

False spirit is a temporary improvement in the spirit of critically ill patients, indicating a clinical warning rather than a good sign.

Manifestations of false spirit include: a long-term ill person who has lost spirit suddenly appears more spirited, with bright eyes and excessive chatter, wanting to see loved ones; or a patient whose voice is weak and intermittent suddenly becomes loud; or a person whose complexion is dull suddenly has flushed cheeks; or someone with no appetite suddenly shows increased hunger.

The distinction between false spirit and genuine improvement lies in the suddenness of false spirit, which does not correspond to the overall condition of the illness, being only temporary and localized. The transition from losing spirit to gaining spirit indicates a genuine improvement in the overall condition, which occurs gradually.

False spirit arises from extreme depletion of qi and jing, where the yin fails to contain the yang, leading to a temporary appearance of improvement. This is a critical sign of impending separation of yin and yang, likened by ancient practitioners to a “flickering lamp” or “returning light.”

4. Insufficient Spirit

Insufficient spirit is a mild form of losing spirit, differing only in degree. It lies between having spirit and losing spirit, commonly seen in patients with deficiency syndromes.

Clinical manifestations of insufficient spirit include: lack of energy, forgetfulness, drowsiness, low voice, reluctance to speak, lethargy, and sluggish movements. This often relates to deficiencies in the heart and spleen or insufficient kidney yang.

5. Abnormal Consciousness

Abnormal consciousness is also a manifestation of losing spirit, but it fundamentally differs from losing spirit due to depletion of qi. It generally includes symptoms of agitation and conditions such as mania, delirium, or other mental disorders. These are determined by specific pathological mechanisms and disease patterns, and their manifestations of losing spirit do not necessarily indicate the severity of the condition.

Agitation refers to a state of internal heat and restlessness, with symptoms of fidgeting. Agitation and restlessness are different; agitation is a subjective symptom, while restlessness is an objective symptom, such as mania or hyperactivity, often related to heat in the heart. It can be seen in conditions of internal heat, phlegm-heat disturbing the heart, or yin deficiency with excess heat.

Mania is characterized by extreme agitation, shouting, and violent behavior, often resulting from liver qi stagnation transforming into fire, or phlegm-heat disturbing the spirit.

Epilepsy presents as sudden loss of consciousness, drooling, and limb convulsions, with a return to normalcy afterward. This is often due to liver wind with phlegm obstructing the clear orifices, or phlegm-heat disturbing the heart, leading to liver wind.

(2) Observing Color

Observing color involves the physician examining the patient’s facial color and luster. Color refers to hue changes, while luster refers to brightness changes. Ancient practitioners categorized colors into five types: green, red, yellow, white, and black, known as the five-color diagnosis. The five-color diagnosis applies to both the face and the entire body, hence the terms facial five-color diagnosis and comprehensive five-color diagnosis. However, due to the most pronounced changes in the face, facial color observation is often used to explain the five-color diagnosis.

When observing facial color, it is essential to distinguish between normal and pathological colors.

1. Normal Color

Normal color refers to the facial hue during a person’s normal physiological state. Normal color can be divided into primary and secondary colors.

(1) Primary Color

Primary color refers to the basic skin tone that does not change throughout a person’s life. Due to differences in ethnicity, constitution, and physique, individual skin tones may vary. The Chinese people belong to the yellow race, and generally, the skin tone is slightly yellow, which is considered the normal color. Based on this, some individuals may have slight variations such as being slightly whiter, darker, or redder.

(2) Secondary Color

Secondary color refers to changes in facial color and skin tone due to environmental factors. For example, changes in facial color can occur with seasonal, daily, or weather variations, as well as due to age, diet, lifestyle, temperature, and emotional changes.

In summary, normal color can be divided into primary and secondary colors, with the common characteristics being brightness and luster.

2. Pathological Color

Pathological color refers to the facial color and luster during a disease state, encompassing all abnormal colors aside from the normal colors mentioned above. Pathological colors include green, yellow, red, white, and black. The main diseases associated with each color are described as follows:

(1) Green Color

Associated with cold syndromes, pain syndromes, blood stasis syndromes, convulsions, and liver diseases.

Green color indicates stagnation of the meridians, leading to obstruction of qi and blood flow. Cold causes contraction and stagnation; when cold accumulates in the blood vessels, it leads to qi stagnation and blood stasis, resulting in a green complexion. Liver diseases often involve stagnation of qi and blood, which can also present as green color. Additionally, liver diseases can lead to internal wind, causing convulsions, which may also present as green.

For example, a complexion that is dark green or pale blue often indicates internal cold; a grayish-green complexion with cyanotic lips may suggest blood stasis; in children with high fever, a cyanotic complexion around the nose, between the eyebrows, and around the lips may indicate a premonition of convulsions.

(2) Yellow Color

Associated with dampness syndromes and deficiency syndromes.

Yellow color indicates spleen deficiency and damp accumulation. The spleen governs transformation and transportation; if the spleen fails to function properly, dampness accumulates; or if the spleen is deficient, it cannot transform food essence into qi and blood, leading to a yellow complexion.

For example, a pale yellow complexion may indicate spleen and stomach qi deficiency, where the nutrients cannot nourish the face; a yellow complexion that is swollen may indicate spleen deficiency with dampness accumulation; a bright yellow complexion resembling orange peel indicates damp-heat; a dark yellow complexion resembling smoke indicates cold-damp obstruction.

(3) Red Color

Associated with heat syndromes.

When qi and blood are heated, they flow vigorously, leading to a red complexion. Heat syndromes can be classified into excess and deficiency types. In excess heat syndromes, the entire face appears red; in deficiency heat syndromes, only the cheeks may be flushed. Additionally, if a patient with a severe condition has a red complexion, it often indicates a deficiency of qi, where the yin fails to contain the yang, leading to excess yang.

(4) White Color

Associated with deficiency-cold syndromes and blood deficiency syndromes.

White color indicates weakness of qi and blood, which cannot nourish the body. Insufficient yang leads to weak circulation of qi and blood, or excessive loss of blood, resulting in a pale complexion.

For example, a pale and swollen complexion often indicates insufficient yang; a pale and thin complexion may suggest deficiency of ying and blood; a sallow complexion may indicate severe deficiency of yang or excessive blood loss.

(5) Black Color

Associated with kidney deficiency syndromes, water retention syndromes, cold syndromes, pain syndromes, and blood stasis syndromes.

Black color indicates excess cold and water. Due to kidney yang deficiency, water retention occurs, leading to internal cold and blood stagnation, resulting in a dark complexion.

A dark and dry complexion often indicates long-term depletion of kidney essence, with deficiency fire scorching the yin; dark circles around the eyes may suggest kidney deficiency with water retention; a dark complexion with severe pain may indicate cold stagnation.

(3) Observing Body Shape

Observing body shape involves examining the overall appearance of the body, including strength, weight, and body type, as well as the trunk and limbs, skin, muscles, and bones. The body’s structure reflects the vitality of the internal organs, as internal vitality correlates with external strength.

Individuals with a strong physique typically exhibit robust bones, a broad chest, strong muscles, and moist skin, reflecting abundant vitality in the internal organs. Even if they are ill, their righteous qi remains intact, suggesting a favorable prognosis.

Conversely, individuals with a weak physique often display slender bones, a narrow chest, thin muscles, and dry skin, indicating insufficient vitality in the internal organs, making them prone to illness, and if they become ill, the prognosis is often poor.

Being overweight with low appetite indicates a condition of excess with deficiency of qi, often accompanied by pale skin, fatigue, and lack of energy. Such patients may also experience damp accumulation due to yang deficiency, leading to phlegm formation, hence the saying, “overweight individuals often have dampness.””>

If an individual is thin with low appetite, it often indicates spleen and stomach deficiency. A thin physique with dry skin and often accompanied by flushed cheeks, tidal fever, and night sweats suggests deficiency of yin and blood, leading to internal heat, hence the saying, “thin individuals often have heat.” In severe cases, extreme weight loss may indicate a critical state of internal organ vitality depletion.

(4) Observing Posture

Normal posture is characterized by comfort, naturalness, fluid movement, and responsiveness, with the ability to sit, stand, walk, and lie down as desired. In illness, due to the fluctuations of yin, yang, qi, and blood, posture may exhibit abnormal changes, with different diseases producing distinct pathological postures. Observing posture primarily involves examining the patient’s movements, stillness, abnormal actions, and postural changes related to the disease. For instance, if a patient’s eyelids, face, lips, or fingers (toes) tremble, it may indicate a premonition of spasms in external diseases; in internal injuries or mixed diseases, it often suggests blood deficiency and yin depletion, leading to insufficient nourishment of the meridians.

Convulsions or rigidity of the limbs, stiffness of the neck and back, and arching of the back are indicative of spasms, commonly seen in conditions of extreme heat generating internal wind, high fever in children, or heat entering the blood. Additionally, conditions such as epilepsy, tetanus, and rabies can also lead to spasms. Trembling is often seen during malaria attacks or as a sign of impending sweating due to a struggle between external pathogens and the body’s defenses. Weakness and lack of strength in the limbs, with impaired movement but no pain, indicate paralysis. Joint swelling or pain that hinders movement indicates arthralgia. Inability to use the limbs, numbness, rigidity, or weakness indicates paralysis. If a person suddenly collapses but continues to breathe, it often indicates a condition of syncope.

Pain syndromes also exhibit specific postures. For example, if a patient protects their abdomen while leaning forward, it often indicates abdominal pain; if a patient protects their lower back and has difficulty moving, it suggests lower back pain; if a patient suddenly stops walking and protects their heart, it may indicate true heart pain; if a patient frowns and holds their head, it often indicates headache.

If a patient is bundled up in clothing, they likely have a preference for warmth and dislike cold, indicating either exterior cold or interior cold; if a patient frequently wants to uncover themselves, they likely dislike heat and prefer coolness, indicating either exterior heat or interior heat. If a patient bends their head and avoids light, it may indicate eye disease; if a patient tilts their head back and seeks light, it may indicate a febrile disease, with yang conditions preferring coolness and wanting to be around people, while yin conditions prefer warmth and solitude, disliking noise.

In terms of sitting posture, if a patient prefers to lean forward, it may indicate lung deficiency; if a patient prefers to recline, it may indicate lung excess with reversed qi; if a patient cannot lie down without experiencing reversed qi, it may indicate cough or lung distension, or water retention in the chest and abdomen. If a patient cannot tolerate sitting and feels fatigued or dizzy when sitting, it may indicate deficiency of both qi and blood or excessive blood loss. If a patient does not want to get up, it may indicate deficiency of yang. Restlessness in sitting or lying down is a sign of agitation or abdominal distension and pain.

In terms of lying posture, if a patient often lies outward and can easily turn, it indicates a yang condition, heat condition, or excess condition; conversely, if a patient prefers to lie inward and cannot turn, it may indicate a yin condition, cold condition, or deficiency condition; if a patient is so ill that they cannot turn themselves, it often indicates extreme depletion of qi and blood, suggesting a poor prognosis. Curling up into a ball may indicate yang deficiency with cold or severe pain; conversely, lying flat with extended legs may indicate a yang condition with excess heat.