Introduction to the Eight Major Differentiation Treatment Methods in TCM

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) places great emphasis on syndrome differentiation and treatment. This approach encapsulates the high-level wisdom involved in diagnosing and treating diseases; it is not merely a set of techniques but a systematic methodology developed by experienced practitioners over time. It can be considered a crystallization of Chinese medical wisdom. This methodology is not only beneficial for practitioners in treating illnesses but has also been adopted by many entrepreneurs and managers!

As the saying goes, “If one is not a good minister, they should at least be a good doctor.” If we compare a diseased body to a company, a department, or a country, once a person masters such a wise methodology, they will undoubtedly approach tasks and problem-solving with more method, practicality, and strength!

Eight Principles Differentiation

The Eight Principles Differentiation is based on the materials obtained from the four examinations: observation, listening, inquiry, and pulse-taking. It involves comprehensive analysis to explore the nature of the disease, the affected areas, the severity of the condition, the strength of the body’s response, and the comparison of the forces of righteousness and evil, categorizing them into eight types of syndromes: Yin, Yang, Exterior, Interior, Cold, Heat, Deficiency, and Excess. This is a fundamental method of syndrome differentiation in TCM, encompassing various differentiation methods and summarizing their commonalities, playing a role in simplifying complexity and highlighting key points during the diagnostic process.

Six Meridians Differentiation

This is a treatment method based on the progression of externally contracted diseases. It can be divided into three Yin and three Yang categories. In the Han Dynasty, Zhang Zhongjing wrote the “Shang Han Lun” (Treatise on Cold Damage), which conducted a comprehensive analysis of various syndromes during the evolution of externally contracted diseases, summarizing their affected areas, tendencies of cold and heat, and the dynamics of evil and righteousness, distinguishing them into the six meridians: Taiyang, Yangming, Shaoyang, Taiyin, Jueyin, and Shaoyin. For thousands of years, it has effectively guided the syndrome differentiation and treatment in TCM.

Etiological Differentiation

Etiological differentiation is the foundation of differentiation for externally contracted diseases, judging the type of disease based on the patient’s characteristics and symptoms. It is divided into four aspects: the seven emotions, six excesses, external injuries, and diet and labor. The seven emotions include joy, anger, worry, thought, sadness, fear, and shock. The six excesses refer to wind, cold, heat, dampness, dryness, and fire. External injuries include injuries from sharp objects, insect bites, and falls. Diet and labor refer to food intake, labor, and sexual activity.

Health and Blood Differentiation

This differentiation method is used for externally contracted warm diseases, categorizing the disease into four stages, each representing a progression from superficial to deep. In fact, different degrees also exhibit different manifestations. The disease may affect the skin and lungs, with Qi involved in the stomach and intestines, gallbladder, etc.

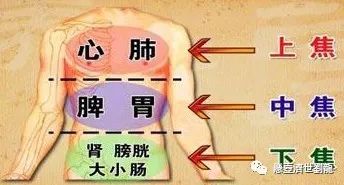

San Jiao Differentiation

According to the concept of the three Jiao (San Jiao) in the “Nei Jing” (Inner Canon), the organs of the human trunk are divided into three parts: upper, middle, and lower. The throat to the chest is the upper Jiao; the abdomen is the middle Jiao; the lower abdomen and the two Yin are the lower Jiao. This differentiation is summarized based on the six meridian differentiation in the “Shang Han Lun” and the differentiation of Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood by Ye Tianshi, combined with the characteristics of the transmission of warm diseases.Generally, it includes three areas: symptoms of the upper, middle, and lower Jiao. Symptoms of the upper Jiao may include thirst and cough. The middle Jiao may present with constipation, abdominal distension, and difficulty urinating. The lower Jiao may show symptoms like deafness and twitching of the hands and feet.

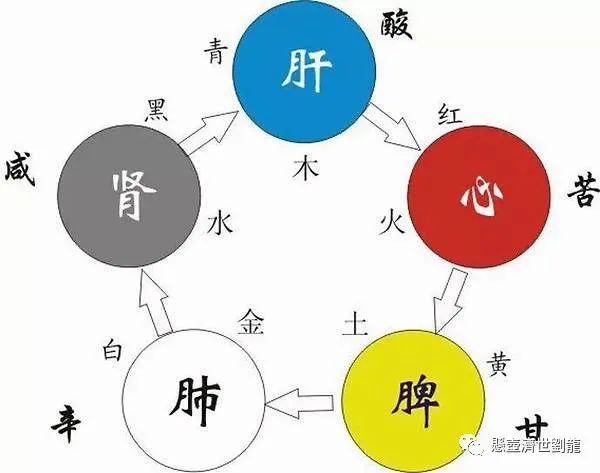

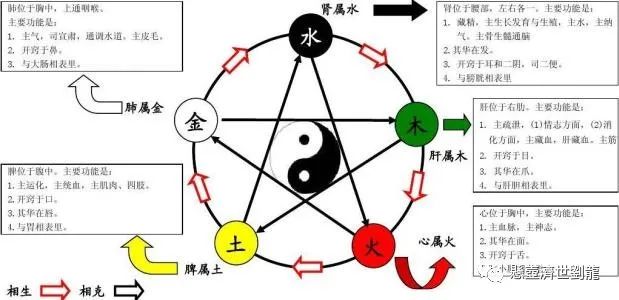

Zang-Fu Differentiation

Zang-Fu differentiation is based on the physiological functions and pathological characteristics of the Zang and Fu organs, identifying the location of the disease and the changes in Yin and Yang, Qi and Blood, deficiency and excess, cold and heat, providing a basis for treatment. This method mainly reflects the pathology based on the Zang and Fu organs.In fact, it also reflects the dynamics of righteousness and evil, distinguishing the nature or location of the disease.It includes three parts: differentiation of Zang diseases, Fu diseases, and Zang-Fu diseases.

Meridian Differentiation

Meridian differentiation is based on the physiological and pathological conditions of the meridians and their associated Zang and Fu organs, analyzing the clinical manifestations of the meridians and related Zang and Fu organs under pathological conditions, thereby clarifying the location of the disease, its etiology, pathogenesis, and characteristics, providing a basis for treatment.The meridians are crucial to the human body and thus are a key aspect of TCM differentiation.It includes diseases of the twelve meridians and the eight extraordinary meridians.

Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids Differentiation

This is the last differentiation method, using the theory of Qi, Blood, and body fluids to analyze the causes and results of their pathological changes. The eight differentiation methods used in TCM are very common and effective.Of course, each of the eight differentiation methods has its own focus and is suitable for different clinical scenarios. Only by mastering these eight differentiation methods and achieving the state of “the skill lies in the heart” can one truly be considered a great physician!

Other Differentiation Methods in TCM Diagnosis

Six Meridians Differentiation

Clinical Manifestations of Taiyang Disease

| Taiyang Meridian Syndrome | Taiyang Fu Syndrome | |||

| Taiyang Wind Syndrome | Taiyang Cold Damage Syndrome | Taiyang Water Retention Syndrome | Taiyang Blood Retention Syndrome | |

| Clinical Manifestations | Fever, aversion to wind, sweating, floating and relaxed pulse, or nasal congestion, dry retching | Chills, fever, stiffness and pain in the head and neck, body aches, no sweating, tight floating pulse, or shortness of breath | Fever and chills, difficulty urinating, fullness in the lower abdomen, thirst, or vomiting upon drinking water, floating or rapid pulse | Urgent or hard fullness in the lower abdomen, spontaneous urination, possible mania or forgetfulness, dark black stools, deep and choppy or deep and tight pulse |

Clinical Manifestations of Yangming Disease

| Yangming Meridian Syndrome | Yangming Fu Syndrome | |

| Clinical Manifestations | High fever, no aversion to cold, but aversion to heat, profuse sweating, great thirst, irritability, flushed face, coarse breathing, yellow dry tongue, and large pulse | Afternoon tidal fever, sweating in hands and feet, abdominal distension and pain, tenderness upon palpation, constipation, severe cases may lead to delirium, irritability, and insomnia, yellow thick dry tongue, or prickly and even blackened tongue, solid or rapid pulse |

Symptoms of Shaoyang Eight Major Syndromes:

Bitter taste in the mouth, dry throat, dizziness, alternating chills and fever, fullness in the chest and hypochondria, lack of desire to eat, irritability and nausea, wiry pulse.

Clinical Manifestations of Taiyin Disease:

Abdominal fullness and vomiting, inability to eat, diarrhea, no thirst, occasional abdominal pain, cold limbs, deep and slow or weak pulse.

Clinical Manifestations of Shaoyin Disease

| Shaoyin Cold Transformation Syndrome | Shaoyin Heat Transformation Syndrome | |

| Clinical Manifestations | No fever, aversion to cold, desire to sleep, cold limbs, clear diarrhea, inability to eat, or vomiting upon eating, or body heat without aversion to cold, even flushed face, thin and rapid pulse | Restlessness and insomnia, dry mouth and throat, red tip of the tongue, thin and rapid pulse |

Clinical Manifestations of Jueyin Disease:

Thirst, heartburn, hunger without desire to eat, vomiting of roundworms.

Transmission Forms of Six Meridians Disease:

1. Transmission through meridians (transmission along the meridian, transmission across meridians, transmission between exterior and interior)

Transmission along the meridian: Taiyang – Yangming – Shaoyang – Taiyin – Shaoyin – Jueyin

Transmission across meridians: transmission across one or two meridians

Transmission between exterior and interior: mutual transmission between two meridians, such as Taiyang disease transmitting to Shaoyin disease

2. Direct entry: when a cold damage disease initially does not enter through the three Yang meridians but directly enters the three Yin meridians.

3. Combined disease: when a cold damage disease does not undergo transmission, and symptoms of two or three meridians appear simultaneously, such as Taiyang and Yangming combined disease, Taiyin and Taiyang combined disease, etc.

4. Concurrent disease: when symptoms of one meridian have not resolved, and symptoms of another meridian appear, such as concurrent Taiyang and Shaoyin disease, concurrent Taiyin and Shaoyin disease, etc.

Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood Differentiation

Wei stage syndrome:

Fever, slight aversion to wind and cold, little sweating, headache, general discomfort, slight thirst, red tip of the tongue, thin yellow coating, floating and rapid pulse, or cough and sore throat.

Qi stage syndrome:

Fever without aversion to cold, thirst, sweating, irritability, red urine, red tongue, yellow coating, rapid and forceful pulse.

Evil heat affecting the lungs, causing lung Qi to be obstructed, accompanied by cough, chest pain, and yellow thick phlegm.

Heat disturbing the chest, causing restlessness and irritability, leading to insomnia.

Heat obstructing the intestines, causing tidal fever, abdominal distension and pain, tenderness upon palpation, possible delirium, constipation or foul-smelling diarrhea, yellow dry coating, possibly even black and prickly tongue, solid pulse.

Heat obstructing the gallbladder, causing Qi to reverse, leading to bitter taste, hypochondriac pain, irritability, and dry retching, wiry and rapid pulse.

Ying stage syndrome:

High fever at night, slight thirst or no thirst, irritability and insomnia, possible delirium, rashes, red tongue without coating, thin and rapid pulse.

Blood stage syndrome:

High fever at night, restlessness, possible delirium, bleeding symptoms, purplish-black rashes, deep red tongue, thin and rapid pulse, possible twitching of hands and feet.

Transmission forms of Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood disease:

Sequential transmission: Wei stage — Qi stage — Ying stage — Blood stage, transmitted in order.

Reverse transmission: when the evil enters the Wei stage but does not pass through the Qi stage and directly enters the Ying and Blood stages.

San Jiao Differentiation

Clinical manifestations of upper Jiao disease:

Fever, slight aversion to wind and cold, headache, sweating, thirst, cough, red tip of the tongue, floating and rapid pulse, or only heat without cold, cough, shortness of breath, thirst, yellow tongue, rapid pulse; severe cases may present with high fever, profuse sweating, delirium, or stupor, red tongue.

Clinical manifestations of middle Jiao disease:

1. From dryness: high fever, red face, coarse breathing, abdominal fullness, constipation, delirium, thirst for cold drinks, dry mouth and cracked lips, dark red tongue with yellow dry or black prickly coating, solid and forceful pulse.

2. From dampness: high fever without elevation, heavy pain in the head and body, chest and abdominal fullness, nausea and vomiting, unsatisfactory bowel movements or diarrhea, yellow greasy tongue coating, slippery and rapid pulse.

Clinical manifestations of lower Jiao disease:

High fever, red cheeks, hot palms and soles, dry mouth and throat, fatigue, deafness, or twitching of hands and feet, palpitations, red tongue with little coating, thin and rapid or weak pulse.

Transmission forms of San Jiao disease:

Sequential transmission: upper Jiao — middle Jiao — lower Jiao, transmitted in order.

Reverse transmission: when the evil transmits from the lung Wei to the pericardium.

“Using Medicine Like Warfare” —

The theory of “Cold Damage and Warm Disease” was pioneered by the Han Dynasty physician Zhang Zhongjing in his work “Shang Han Za Bing Lun” (Treatise on Cold Damage and Miscellaneous Diseases), establishing a standard for the differentiation and treatment of externally contracted febrile diseases. The famous physician Ye Tianshi in the Qing Dynasty developed the theory of warm diseases, proposing that cold damage primarily involves the six meridians, while warm diseases focus on Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood, representing two distinct fields of study. Since Ye’s theory emerged, it has sparked a long-standing debate in the TCM community regarding cold damage and warm diseases. Liu Long has conducted extensive research, believing that the six meridians and Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood should not be viewed as entirely separate concepts. Instead, one should carefully analyze the specific syndromes they manifest, requiring a thorough examination of their clinical presentations. First, a meticulous investigation of the concepts of disease and syndrome is necessary, supported by ample data to demonstrate that the term “cold damage” originally referred to all externally contracted diseases, including what modern practitioners refer to as warm diseases. Warm diseases encompass many specific disease names, causes, mechanisms, and treatment principles, which are also fundamentally discussed in the “Shang Han Lun”. In a certain sense, cold damage and warm diseases are synonymous. Furthermore, the practical content analysis shows that the “Shang Han Lun” primarily uses the Eight Principles as a guide, based on the meridians and Zang-Fu organs (including the San Jiao), differentiating based on the nature of the pathogenic factors, the affected areas, the dynamics of righteousness, and the manifestations of syndromes, which serves as a common basis for TCM treatment. Warm diseases are a branch of cold damage, and thus are not exceptions. Zhang Zhongjing’s principles of differentiation and treatment based on the six meridians elucidate the inseparable relationship between meridians, Zang-Fu organs, and Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood. It is pointed out that “the six meridians are based on the substance of the meridians and Zang-Fu organs; if this is not acknowledged, many original texts of the ‘Shang Han Lun’ cannot be explained. Moreover, the six meridians inherently include the clinical manifestations of the San Jiao and Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood, which cannot exceed the scope of differentiation and treatment based on meridians and Zang-Fu organs. Those who advocate separating warm diseases from cold damage disrupt the inseparable relationship between the six meridians and the San Jiao, severing the various organic connections between meridians and Zang-Fu organs, thereby undermining the fundamental theories of integrity and dialectics in TCM.

Based on this, Liu Long believes that warm diseases are merely a branch of cold damage. The theory of warm diseases enriches and develops the understanding and treatment of externally contracted febrile diseases in certain aspects, but it is inappropriate to mechanically separate the two. Instead, one should approach it practically, integrating the mechanisms and treatment methods of cold damage and warm diseases into a cohesive whole, which is beneficial for the diagnosis and treatment of externally contracted febrile diseases.

Regarding the study of meridian theory, “Meridian theory is the theory of the interconnections of traditional Chinese medicine, explaining the interrelationships and close influences between various parts of the human body, indicating that these connections are important bases for the life activities, disease mechanisms, and diagnosis and treatment of the human body. It embodies the holistic view in traditional Chinese medicine theory. Although current scientific levels cannot find its substantial content, with the development of science, many scholars at home and abroad have begun to find some clues related to meridians from experiments, and the phenomenon of meridian transmission has been further confirmed by extensive clinical practice. Meridians play crucial roles in the physiological state of the human body, such as transporting Qi and Blood, running Ying and Wei, connecting Zang and Fu, and nourishing tissues. When the body undergoes abnormal changes, meridians reflect symptoms and transmit pathogenic factors. When acupuncture or herbal medicine is applied, they also receive stimulation and transmit therapeutic effects. The examples of acupuncture point selection based on meridian theory and the theory of herbs entering specific meridians illustrate its significant clinical value.

Meridians include three components: “points,” “lines,” and “planes.” The tender points and sensitive areas discovered by modern physicians also serve as evidence and enrichment of meridian theory. Some believe that certain tender points do not entirely correspond with the acupuncture points of the meridians. This is because acupuncture points are only a part of meridian theory; it also includes collaterals, extraordinary meridians, sinews, skin areas, and root and branch relationships. The distribution of meridians in the human body should not only be understood as connections of “lines” or “points” but should also be comprehended from the broader “planes” of their distribution.

Regarding the meanings of “movement” and “disease caused” in the twelve meridians, there have been various interpretations over the centuries. Physicians have discussed it from perspectives of Yin-Yang, Qi-Blood, internal and external causes, and meridians and Zang-Fu organs, among others. Qiu Peiran believes that although various interpretations are close to the truth, the original meaning of “movement” in the “Nei Jing” refers to the pathological changes of meridian Qi, while “disease caused” refers to the diseases treated by the meridians and acupuncture points. The two complement and confirm each other. Symptoms arising from pathological changes are termed movement diseases, which correspond to the treatment scope of the acupuncture points; the diseases treated by the twelve meridians also arise from the abnormalities of the Qi in those meridians. Analyzing the character “movement” indicates the disturbance of meridian Qi, while the character “master” in “disease caused” implies the meaning of governance and treatment. The reason for the two parts of the description is that it is merely a compilation of materials obtained from the clinical observation of symptoms and treatment experiences by ancient physicians. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand that they have both repetition and supplementation in content.

The issue of the eight extraordinary meridians has not received sufficient attention in the academic community. For a long time, the symptoms and treatments of the eight extraordinary meridians have not been deeply explored. Liu Long believes that “the medicinal herbs and formulas used in clinical applications of TCM can almost treat diseases of the extraordinary meridians,” and the same applies to acupuncture treatment. Except for the Ren and Du meridians, the other six meridians’ Qi points are all associated with the acupuncture points of the twelve meridians, thus having interconnected significance in treatment. The methods for treating extraordinary meridian diseases do not stray from the meridians or Zang-Fu organs they govern, using herbs or acupuncture points that can enter the original meridians, applied appropriately, can yield excellent results.

During the Ming Dynasty, physician Zhang Jingyue faced criticism from many later physicians for his frequent use of cooked Rehmannia. After long contemplation and personal practice, he recognized Jingyue’s unique strengths. For example, he often used large doses of cooked Rehmannia and Angelica in combination with Pinellia, Poria, and Licorice to cure many difficult cases of phlegm accumulation, breathlessness, and poor appetite that had been ineffective with conventional methods for a long time. He broke the long-standing taboo against using cooked Rehmannia for chest tightness and poor appetite. He lamented that doctors “can do what they can, but cannot do what they cannot,” and adhered to the valuable saying, “To truly understand this matter, one must practice it.”

Qing Dynasty physician Zhu Danxi made valuable contributions to TCM. His academic characteristics can be summarized in six points: life continuity is due to movement, all movements belong to fire, primarily the action of the ministerial fire; excessive movement of ministerial fire can lead to disease; essence and blood are easily consumed and difficult to generate; when Yin essence is abundant, Yang Qi can continuously surge throughout the life process, hence the saying, “Yang is often sufficient, while Yin is often insufficient”; diseases often arise from deficiency of righteous Qi, thus treatment should not advocate harsh attacks, but also oppose excessive supplementation, often employing methods that “treat disease without harming righteousness, support righteousness without obstructing evil”; Qi in excess can cause fire to flare, while excess fire can also lead to Qi stagnation, and Qi and fire stagnation often attach to tangible evils; Liu Hejian focused on fire but failed to deeply understand the source of fire’s burning, while Li Dongyuan believed that “fire and original Qi cannot coexist,” not realizing that ministerial fire has the function of nourishing the body; Zhang Zihe focused on attacking but neglected the key role of righteous Qi in treating diseases. Zhu Danxi absorbed the strengths of these three schools while compensating for their biases; his prescriptions emphasized nourishing Yin and clearing, draining, benefiting, and dispersing, as well as adjusting.

“Liu’s medical theory emphasizes ‘sincerity’,” and “Liu’s selection of formulas aims for ‘excellence’,” systematically discussing the “Qian Jin Yao Fang” (Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold) and “Qian Jin Yi Fang” (Supplementary Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold), summarizing the characteristics of his formula selection as: simplicity and effectiveness, balanced and winning, unique and unconventional, yet orderly, providing great inspiration. The combination of ginger and rhubarb, and the pairing of human and yellow with rhubarb, reflect the wonderful use of “contrary, stimulating, reverse, and following” in formula creation. Treating difficult and miscellaneous diseases with complex formulas or unique combinations can lead to recovery from chronic illnesses and serious conditions.

For treating difficult and critical diseases, using harsh medicines to cure diseases is already considered a good physician, but it cannot be called a skilled craftsman. This is because harsh medicines often harm the original Qi; although the disease may be cured, the body’s vitality is secretly consumed, which is ultimately not an ideal treatment method. If one can use mild and harmonious medicines to solve problems, eliminating evil without harming righteousness, achieving “miraculous effects within simplicity,” is far superior to using harsh medicines for treatment.

The key to using ancient formulas to treat modern diseases lies in the two characters “proficient”. To learn ancient formulas, one must first understand the original meaning of the formulas and grasp their subtleties to integrate them effectively. In clinical practice, it is not uncommon for ancient formulas to align with modern diseases; when applying ancient formulas, one sometimes needs to grasp the main symptoms to adjust the formulas accordingly for effectiveness; at other times, using the original ancient formulas can yield remarkable results. There are established methods for formula creation, and one must know how to adapt and change based on common principles, with the subtleties of change residing in the heart.

When establishing formulas and prescribing medicines to enhance efficacy, it can be summarized in four characters: “exquisite, unique, skillful, and broad”.

Prescriptions should be exquisite. The so-called “exquisite” refers to the utmost appropriateness and difficulty of achieving.

Formulating should be unique. “Using medicine is like using troops; military strategy has regular forces and unique tactics. The way of using medicine is fundamentally the same.”

Broadness is the foundation of the three aspects of exquisite, unique, and skillful; excellence comes from broadness, uniqueness does not stray from the regular, and skillfulness arises from familiarity. The so-called “broad” means to read extensively and gather various formulas. The more treatment methods a physician masters, the better. For example, in treating dizziness, many modern practitioners are confined to the theories of “Yang transformation into internal wind” and “no phlegm, no dizziness,” using formulas like Tianma Gou Teng Yin and Banxia Baizhu Tianma Tang as their mainstays, unaware that liver Yang not rising, lower Jiao deficiency and cold, kidney essence deficiency, and Qi and Blood deficiency can all cause dizziness. Many corresponding ancient formulas are also effective for treating dizziness. A physician with a wealth of treatment methods in their mind can respond appropriately in clinical practice.

“The more one reads, the more one feels their knowledge is lacking. Life is short, and knowledge is infinite.”

“A lifetime of study is a process of continuous learning, continuous thinking, and continuous striving.” The essence of the six meridian diseases. “Shang Han”

Qiu Peiran’s interests in learning are very broad. In his early years, while studying in a private school, he not only studied ancient texts but also extensively explored philosophy, history, literature, mathematics, chemistry, and medicine. Later, he devoted himself to medicine, and his reading and knowledge-seeking were not limited to medical texts. Among the generations of physicians, the pragmatic spirit is another characteristic of scholarship; whether in personal conduct or academic pursuits, one must be pragmatic. Pragmatism is not only a matter of academic style but also a significant question for establishing a prosperous nation. Based on this spirit, he treated every ancient formula and herb with seriousness, seeking their underlying reasons.

In studying TCM, one must first learn the theoretical foundations of TCM well and have considerable practical experience. The key is to deeply understand the comprehensive content of TCM, and then use scientific methods to organize and gradually improve it. Not only must one be pragmatic in learning TCM theory, but also in clinical summaries and research, especially in research, only in this way can TCM achieve true development.

Consult via WeChat