Today we will learn about the methods of pulse diagnosis. Pulse diagnosis, also known as “qiè mài” (切脉), is a method where the physician uses their fingers to press on the patient’s pulse, perceiving the pulse’s characteristics to understand the condition and diagnose the disease. Pulse diagnosis is an important part of the “four examinations” (望闻问切) in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), and many people find it quite mysterious. In the past, without many diagnostic instruments, traditional Chinese medicine explored the functions of the five organs and six bowels through pulse diagnosis, sensing the state of the body, which is indeed fascinating!

However, from a learning perspective, mastering pulse diagnosis can be quite challenging. Some describe pulse diagnosis as: “like peering into an abyss and meeting floating clouds.” What does this mean? It suggests that pulse diagnosis is as unfathomable as an abyss and as changeable as clouds in the sky, lacking a precise shape.

Pulse diagnosis has a long history. As early as in the “Neijing” (《内经》), methods such as “three parts and nine pulses” (三部九候诊法) and “renying qi kou” (人迎气口诊法) were recorded. The “Nanjing” (《难经》) first advocated the method of “duo qu cun kou” (独取寸口) for pulse diagnosis, which has been followed by later generations. Zhang Zhongjing established the principle of “ping mai bian zheng” (平脉辨证) and created the three-part diagnostic methods of cun (寸), guan (关), and chi (尺) (太溪).

Wang Shuhe’s “Pulse Classic” (《脉经》) inherited the three parts and nine pulses, confirming twenty-four pulse types, making it the earliest existing monograph on pulse studies in China. Li Shizhen’s “Binhuhuaixue” (《濒湖脉学》) recorded twenty-seven pulse types and compiled a “seven-character verse” for easier memorization. Li Shicai’s “Zhenjiayuan” (《诊家正眼》) added disease pulses, totaling twenty-eight pulse types.

Why can pulse diagnosis reflect our bodily conditions? This requires understanding the principles of pulse formation. The pulse is the manifestation of the pulse’s response to the fingers. The formation of the pulse is directly related to the heart’s beating, the patency of the pulse vessels, and the balance of qi and blood. The blood vessels of the human body connect throughout, linking the internal organs and reaching the surface, circulating qi and blood continuously. Thus, the pulse can reflect the overall function of the internal organs, the balance of yin and yang, and the state of qi and blood.

(1) The heart is the main organ for pulse formation.

The heart governs the blood vessels, and the heart’s beating drives the blood to flow normally within the vessels, thus forming the pulse. Therefore, the heart is the main organ for pulse formation, and the heart’s beating is the driving force behind the pulse. The pulse’s frequency, regularity, strength, and weakness correspond to the heart’s beating frequency, rhythm, and intensity. The heart’s beating and the blood’s flow in the vessels are governed by the heart qi and propelled by the zong qi. Thus, “Ling Shu: Xie Ke” (《灵枢·邪客》) states: “Zong qi accumulates in the feet… in the throat, to connect the heart pulse and facilitate breathing.” “Su Wen: Pulse Essentials” (《素问。脉要精微论》) states: “The pulse is the residence of blood.” The pulse is where qi and blood converge, and the structure and function of the vessels can affect the pulse.

(2) The movement of qi and blood is the foundation for pulse formation.

Qi and blood are the fundamental substances that constitute and maintain human life activities, and they are also the material basis for pulse formation. Qi is the commander of blood; it can generate, move, and contain blood. The blood’s flow in the vessels relies on the propulsion and containment of qi; the strength and rhythm of the heart’s beating also depend on qi’s regulation. Blood is the carrier of qi, and the vessels rely on blood to be filled and nourished; the balance of blood directly relates to the pulse’s characteristics. Therefore, qi and blood are crucial for pulse formation. For example, when qi and blood are sufficient, the pulse is harmonious and strong; when qi and blood are insufficient, the pulse is thin and weak; when qi stagnates and blood clots, the pulse is stagnant and obstructed.

(3) The coordination of the five organs ensures normal pulse characteristics.

The formation of the pulse is not only related to the heart and the movement of qi and blood but also requires the coordination and cooperation of the other four organs. The lungs govern qi and control respiration, connecting to all pulses and participating in the generation of zong qi, thus regulating the movement of qi and blood throughout the body, assisting the heart in circulating blood. The spleen and stomach are the foundation of postnatal life, the source of qi and blood generation, determining the amount of “stomach qi” reflected in the pulse; the spleen governs blood, ensuring that blood circulates within the vessels without overflowing, relying on the spleen’s qi to regulate it.

The liver stores blood, regulating blood volume; the liver governs the smooth flow of qi and blood. The kidneys store essence, being the root of both yuan yin and yuan yang, and are also the “root” of the pulse; kidney essence can transform into blood and is one of the important material bases for blood. Thus, the normal formation of the pulse relies on the coordinated functions of the five organs.

Why is it said that learning pulse diagnosis is difficult? Wang Shuhe stated in the preface of the “Pulse Classic”: “The principles of pulse are subtle and difficult to discern; the tight and floating pulses, turning and resembling each other, are easy to understand in the heart but difficult to clarify under the fingers.”

The principles of pulse studies are very intricate and profound. Those who study pulse often find it easy to understand the theory of what pulse types correspond to which diseases, yet in practice, they often struggle to grasp the specific pulse characteristics under their fingers. Many pulse types are very similar, and without careful differentiation, it is difficult to distinguish them. For instance, the string pulse and tight pulse, floating pulse and hollow pulse, etc. The pathological mechanisms reflected by these similar pulses can be vastly different. Mistaking one for the other can lead to misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

Some say that pulse diagnosis must be taught hand-in-hand by a teacher; otherwise, it is difficult to master and excel in pulse diagnosis.

In fact, this statement is somewhat biased. Just like the transmission of TCM, some learn through mentorship or family tradition, while others may have a high level of self-study and can become proficient independently. First, pulse diagnosis, like other diagnostic methods and therapies in TCM, requires repeated training and learning. It is unrealistic to expect that after reading a book on pulse diagnosis today, one can master it proficiently by tomorrow; it requires careful comprehension and repeated practice to gradually master the skills of this diagnostic method.

Wang Shuhe said: “If the pulse is deep, it is hidden; if it is slow, danger will soon arrive.” Therefore, accurately grasping the pulse is an important part of diagnosing diseases. To accurately grasp the pulse, one must not only master the basic theories of pulse studies but also pay special attention to practice and verification. The saying goes, “Reading Wang Shuhe thoroughly is not as good as practicing more in clinical settings.” Through continuous experience and repeated comparisons, one can gradually accumulate rich experience in pulse diagnosis.

Pulse diagnosis itself relies on the physician’s sensitive touch to carefully experience and identify. Therefore, learning pulse diagnosis must involve mastering the basic theories and skills of pulse studies, repeated practice, and careful reflection to achieve the goal of recognizing various pulse types and guiding clinical differentiation.

“Timing”

The best time for pulse diagnosis is early in the morning (ping dan) before getting out of bed and before eating.

In “Su Wen: Pulse Essentials” (《素问·脉要精微论》), it states: “Diagnosis is often done at ping dan, when yin qi has not yet moved, yang qi has not yet dispersed, food has not yet been ingested, the meridians are not yet full, the collaterals are balanced, and qi and blood are not yet chaotic, thus it is possible to diagnose the pulse accurately.”

What is ping dan? It is when the sun has just risen above the horizon, in the early morning before eating or engaging in activities, when yin and yang have not yet moved, qi and blood are not yet chaotic, and the meridians are balanced. At this time, the internal and external environment of the body is relatively stable, and the pulse can accurately reflect the basic physiological state of the body, making it easier to detect pathological pulses. Therefore, this time is the best for pulse diagnosis.

However, this does not mean that pulse diagnosis cannot be performed at other times. The “Pulse Classic” states: “When diagnosing disease pulses, it is not limited to day or night.” Due to current diagnostic conditions, pulse diagnosis can be performed at any time, but there is one requirement: the patient must maintain a calm mood, and the qi and blood must be stable. The examination room should also be kept quiet to minimize external disturbances, which is conducive to the physician’s focused experience of the pulse, leading to accurate diagnosis.

The operation time for pulse diagnosis should be no less than 1 minute for each hand, and about 3 minutes for both hands.

“Position”

During pulse diagnosis, the patient’s position, whether sitting or lying down, should have the arms extended to the sides and laid flat. This allows for smoother blood flow and does not affect the pulse.

The patient’s arms should be extended and not compressed. The arms should be level, and there is a concept called “ping xin,” meaning the position of the hands should be at the same level as the heart. The hands should be at the same horizontal level as the heart. If the hands are raised to feel the pulse, the pulse will definitely be inaccurate. Therefore, strict operation requires the arms to be level and the heart to be level.

“Finger Techniques”

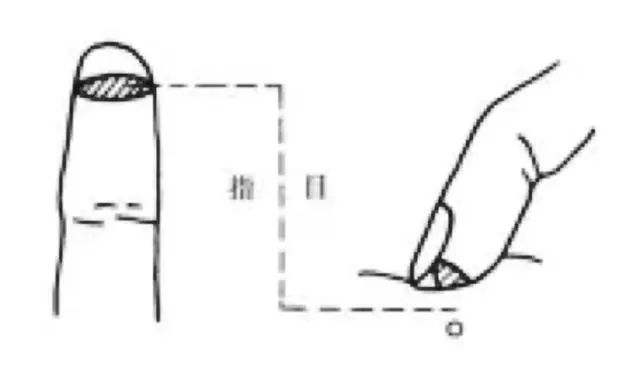

Which fingers should be used for pulse diagnosis? The index finger, middle finger, and ring finger are the three fingers used. When pressing the pulse, the three fingers should be at the same level, slightly bent to be level, about 45 degrees. Where should the fingers touch the pulse? At the “finger tip,” which is between the fingertip and the finger pad, this is what TCM refers to as “finger tip touching the pulse.”

The requirement for “finger tip touching the pulse” is taught in current TCM diagnostic textbooks. The term “finger tip” occasionally appears in literature but is generally not a medical term, and this area does not have a clear anatomical location. The term “finger tip” comes from the “Pulse Theory” (《脉说》), a work by Ye Lin in the Qing Dynasty, which states: “If the tip of the finger is raised like a line, it is called the finger tip, used to press the pulse ridge.” This single sentence is unclear on how it became the gold standard for pulse diagnosis in textbooks.

In clinical practice, it is sufficient to use the finger pad to feel the pulse. The width, thickness, and pulsation of a pulse involve the surrounding muscles and skin, making it difficult to fully assess from just the finger tip.

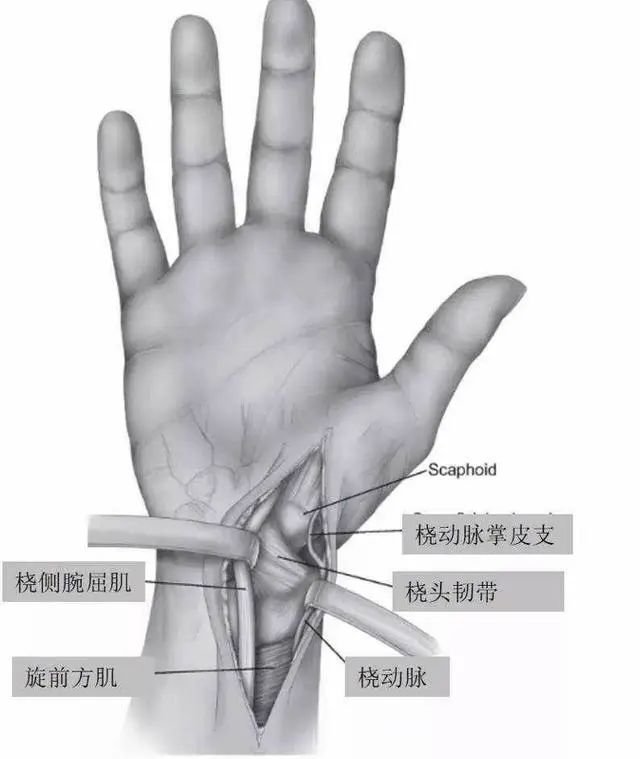

The second issue is the placement of the fingers. According to TCM pulse diagnosis theory, the left and right hands’ cun, guan, and chi correspond to different organs. The left cun corresponds to the heart, the right cun corresponds to the lungs, the left guan corresponds to the liver, the right guan corresponds to the spleen, the left chi corresponds to the kidneys, and the right chi corresponds to the mingmen (命门) etc. If you extend your hand with the palm facing up, you can see the so-called “dorsal high bone.” This protruding bone is located at the radial side of the wrist, behind the thumb, and is called the guan position.

Then, the guan position is the front part—”front” refers to the direction closer to the hand, the front guan is yang, and the back guan is yin. The yang position, which is the front guan, is called cun, and the back position, which is yin, is called chi. This is called “yang cun, yin chi.” Why is it called cun? Because the distance from the dorsal high bone to the wrist crease is exactly one cun according to TCM’s own measurement. And why is it called chi? Because the distance from the guan position to the elbow crease is exactly one chi.

The first step in placing the fingers for pulse diagnosis is to cross the hands, meaning the physician’s left hand presses on the patient’s right hand, and the physician’s right hand presses on the patient’s left hand. Only this method ensures that the index finger is placed on the cun pulse, the middle finger on the guan pulse, and the ring finger on the chi pulse. Many physicians do not do this; one hand holds a pen while the other presses on the left hand and then the right hand. No matter how they press, both hands cannot be on the cun pulse, so this method is incorrect.

If one is indeed accustomed to using only one hand to feel the pulse, they should ensure to use the same hand consistently: the sensory perception of the two hands is different, so using the same hand for pulse diagnosis ensures accurate and effective processing of information by the brain. It is crucial to avoid using the left hand one day and the right hand the next.

The second step is to determine the guan position with the middle finger. The three fingers should first use the middle finger to locate the guan pulse, which is the most prominent area. Sliding along this high point will determine the guan pulse. Additionally, depending on the individual’s size and length, the three fingers should be appropriately spaced.

“Finger Movement”

Finger movement refers to the physician’s use of finger strength, movement, and changes in finger placement to perceive the pulse characteristics. Common finger techniques include lifting, pressing, seeking, total pressing, and single diagnosis.

1. Lifting, Pressing, and Seeking

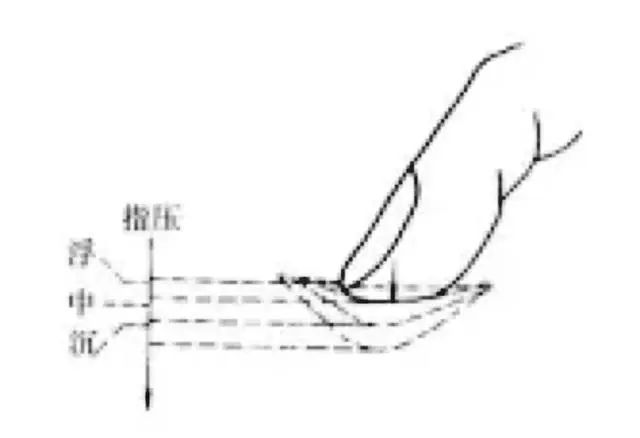

Lifting, pressing, and seeking are the basic finger techniques in pulse diagnosis. They involve varying the pressure of the three fingers to examine the pulse’s floating, sinking, and strength characteristics. As Shou said: “The essentials of holding the pulse are three: lifting, pressing, and seeking. Lightly touching it is called lifting; pressing firmly is called pressing; and applying moderate pressure to seek is called seeking.”

Lifting refers to the physician’s fingers lightly pressing on the cun pulse to perceive the pulse characteristics. The lifting technique is also known as “floating touch.”

Pressing refers to the physician’s fingers applying heavier pressure, even pressing down to the muscles and bones to perceive the pulse characteristics. The pressing technique is also known as “sinking touch.”

Seeking means to search; the physician often uses their fingers from light to heavy, and from heavy to light, pushing and seeking left and right; or carefully searching for the most prominent pulse points in the cun, guan, and chi positions, or adjusting the most appropriate finger strength to find the most distinct pulse characteristics. Applying neither light nor heavy pressure, pressing to the muscles to feel the pulse is called “medium touch.”

During pulse diagnosis, one should carefully observe the changes in the pulse characteristics between lifting, pressing, and seeking.

2. Total Pressing and Single Diagnosis

Total pressing is a method where all three fingers apply equal pressure to diagnose the pulse, allowing for an overall assessment of the cun, guan, and chi positions and the pulse characteristics of both hands.

Single diagnosis is a method where one finger examines a specific pulse. It is mainly used to understand the position, sequence, shape, and characteristics of the pulse in the cun, guan, and chi positions.

When beginning to diagnose pulses in clinical practice, what are the basic steps? Here I will introduce my pulse diagnosis practice method for beginners as a reference.

First, apply even pressure with the three fingers, floating over the cun, guan, and chi positions; then continue with equal pressure for medium touch. Some pulse characteristics can be discovered through this initial examination. For example, when experiencing external wind-cold, the pulse will generally show a floating layer with a tight string-like appearance.

Next, focus on the tip of the index finger, examining the cun pulse from shallow to deep, layer by layer. Then focus on the tip of the middle finger, examining the guan pulse layer by layer, followed by the chi pulse. This way, examine each position and layer, with beginners generally spending no less than one minute on each side to clarify the pulse characteristics.

After completing the examination, repeat the same process on the other hand.

“Calmness”

Calmness refers to the physician’s breathing being steady and even. Why is this important? In ancient times, there were no clocks, and to observe the sun’s movement, if it moved too slowly, one could not tell the time. Thus, one relied on breathing to count the patient’s pulse. The purpose of calmness is twofold: on one hand, it allows the physician to maintain steady breathing, clear the mind, and count the patient’s pulse accurately; on the other hand, calmness helps the physician concentrate, enabling careful differentiation of the pulse characteristics.

“Fifty Pulses”

Fifty pulses emphasize the pulse’s beating. What does “fifty pulses” mean? It means that during pulse diagnosis, one should generally count at least fifty beats. Of course, the focus is not solely on the number; if one is solely counting, “1, 2, 3, 4,” and has counted fifty times without experiencing the pulse’s floating, sinking, strength, and weakness, then the purpose is not achieved! The goal is to emphasize that pulse diagnosis should not be rushed.

One should take a certain amount of time to experience the pulse. Generally, counting fifty or one hundred beats may take about 2 to 3 minutes. The ancients emphasized fifty pulses because it was believed that fifty beats would allow the wei qi (卫气) to circulate throughout the body, reflecting any issues with the five organs and six bowels.

“Elements of Pulse Characteristics”

What exactly should be diagnosed during pulse examination? The identification of pulse characteristics mainly relies on the physician’s finger sensations. There are many types of pulses, and TCM literature often analyzes and summarizes them from four aspects: position, frequency, shape, and state, which relate to the pulse’s frequency, rhythm, the area of manifestation, length, width, the fullness and tension of the pulse vessels, the smoothness of blood flow, and the strength of the heart’s beating.

In modern times, through in-depth understanding of pulse literature and summarizing clinical research data, the main factors constituting various pulse characteristics can be roughly categorized into eight aspects: pulse position, frequency, length, width, strength, rhythm, smoothness, and tension. Mastering these basic elements is crucial for understanding the characteristics and formation mechanisms of various pulse types.

1. Pulse Position

This refers to the depth of the pulse’s manifestation. A superficial pulse is called a floating pulse; a deep pulse is called a sinking pulse. The depth of the pulse is mainly perceived through the pressure applied by the fingers.

2. Frequency

This refers to the pulse’s rate. In a normal adult, a pulse of four to five beats per breath is considered a normal pulse; a pulse of more than five beats per breath is considered a rapid pulse; a pulse of less than four beats per breath is considered a slow pulse.

3. Length

This refers to the axial range of the pulse’s manifestation, meaning a pulse that extends beyond the cun, guan, and chi positions is called a long pulse; a pulse that does not reach the three positions but is seen in the guan or cun positions is called a short pulse.

4. Width

This refers to the radial range of the pulse’s manifestation, meaning the thickness perceived under the fingers. A wide pulse is called a large pulse, while a narrow pulse is called a thin pulse.

5. Strength

This refers to the strength of the pulse. A pulse that feels strong under the fingers is called a solid pulse, while a pulse that feels weak is called a weak pulse.

6. Rhythm

This refers to the regularity of the pulse’s rhythm. It includes two aspects: whether the pulse rhythm is even and whether there are any pauses; and whether the number and duration of pauses are regular.

7. Smoothness

This refers to the smoothness of the pulse’s onset. A pulse that comes smoothly and roundly is called a slippery pulse; a pulse that comes with difficulty and is not smooth is called a rough pulse.

8. Tension

This refers to the urgency or relaxation of the pulse vessels. The tension of the pulse is mainly reflected in the pulse’s length, tension, and the changes in pulsation felt under the fingers. A high tension pulse is like a string pulse or tight pulse; a relaxed pulse can be seen in a slow pulse.

The above are the basic elements that constitute pulse characteristics and the key points for observing pulse characteristics. The identification of pulse characteristics mainly relies on the physician’s finger sensations. Therefore, when examining the pulse, the physician must carefully observe and analyze the various pulse elements comprehensively to gradually master the morphological characteristics of various pulse types and correctly identify and judge various pathological pulses.

Remember to scan the code to follow us, and in the next issue, we will continue discussing.

1. Methods of Pulse Diagnosis

2. Normal Pulse Characteristics and Pathological Pulse Characteristics

3. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Lung Diseases

4. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Heart Diseases

5. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Spleen and Stomach Disorders

6. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Liver and Gallbladder Diseases

7. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Kidney Disorders

8. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids Disorders

9. Differentiating Pulse Diagnosis for Limb and Meridian Disorders

10. What are the Eight Principles?

11. Eight Principles Differentiation: Yin-Yang Differentiation

12. Eight Principles Differentiation: Exterior-Interior Differentiation

13. Eight Principles Differentiation: Cold-Heat Differentiation

14. Eight Principles Differentiation: Deficiency-Excess Differentiation

15. Differentiating External Diseases: Six Meridians Differentiation

16. Differentiating External Diseases: Wei, Qi, Ying, and Blood Differentiation

17. Differentiating External Diseases: Three Jiao Differentiation

18. Differentiating Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids Disorders: Qi Disease Differentiation

19. Differentiating Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids Disorders: Blood Disease Differentiation

20. Differentiating Qi, Blood, and Body Fluids Disorders: Simultaneous Disease Differentiation

21. Differentiating Zang-Fu Disorders: Heart and Small Intestine Disease Differentiation

22. Differentiating Zang-Fu Disorders: Lung and Large Intestine Disease Differentiation

23. Differentiating Zang-Fu Disorders: Spleen and Stomach Disease Differentiation

24. Differentiating Zang-Fu Disorders: Liver and Gallbladder Disease Differentiation

25. Differentiating Zang-Fu Disorders: Kidney and Bladder Disease Differentiation

26. Meridian Differentiation

|

I Copyright Statement: We respect knowledge and labor; please retain copyright information when reprinting. The copyright of the content published on this platform belongs to the relevant rights holders. If there are any improper uses, please feel free to contact us for negotiation. I Submission and Cooperation Email: [email protected] |

Currently, over 100,000 people have followed and joined us.

See more of the latest TCM, herbal medicine, health, and wellness information.

Please long press the code below to follow us.

Traditional Chinese Medicine | Development | Cooperation | Sharing | Public Welfare | Platform

Fuxi Qihuang Platform Home

TCM Video Cloud Aggregation

—— WeChat Online Learning Special Page:

(1) TCM Learning Videos – From Basics to National Medicine Master Course Collection

https://wxc3de.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6

(2) TCM Practical Skills Video – Special Techniques Video Learning Collection

https://wxc3d8ae.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/ey

(3) Traditional Pulse Diagnosis Special Techniques Video Learning

https://wxc3d8e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6

(4) Paid Courses – Famous Doctors and Teachers – Special Techniques

https://wxc3d8576e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZC

(5) Reading Classical TCM Texts – Online Library:

https://wxc3d8a6e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6

(6) Pan-Medical Community – Marketing Lecture Hall

https://wxc3d76e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZC

(7) Latest Updates – Continuous updates for permanent learning

https://wxc3d8ae.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6M

(8) TCM Public Information Cloud Aggregation (Text and Image)

https://wxc3d76e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6MT

(9) Folk Remedies and Secret Recipes Cloud Aggregation (Text and Image)

https://wxc3d8a6e.h5.xiaoe-tech.com/mp/eyJpZCI6M

↓Fuxi Qihuang Platform, Service Number QR Code↓

↓Fuxi Qihuang Platform, Online Learning Entrance↓