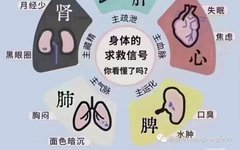

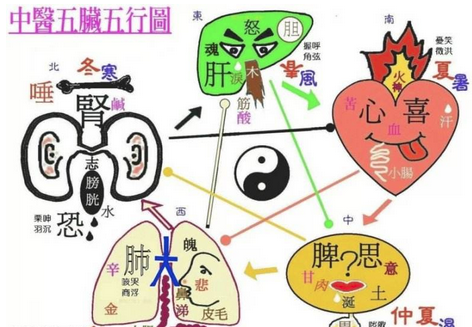

In the perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the human body is an integrated whole centered around the organs (zangfu) and interconnected by meridians (jingluo). The relationship between the five organs (wuzang) and six bowels (liufu) has been particularly emphasized by physicians throughout history, guiding TCM diagnosis, treatment, and health preservation. What exactly is the relationship between these organs? Is the saying “the liver and gallbladder reflect each other” based on reason or mere coincidence?

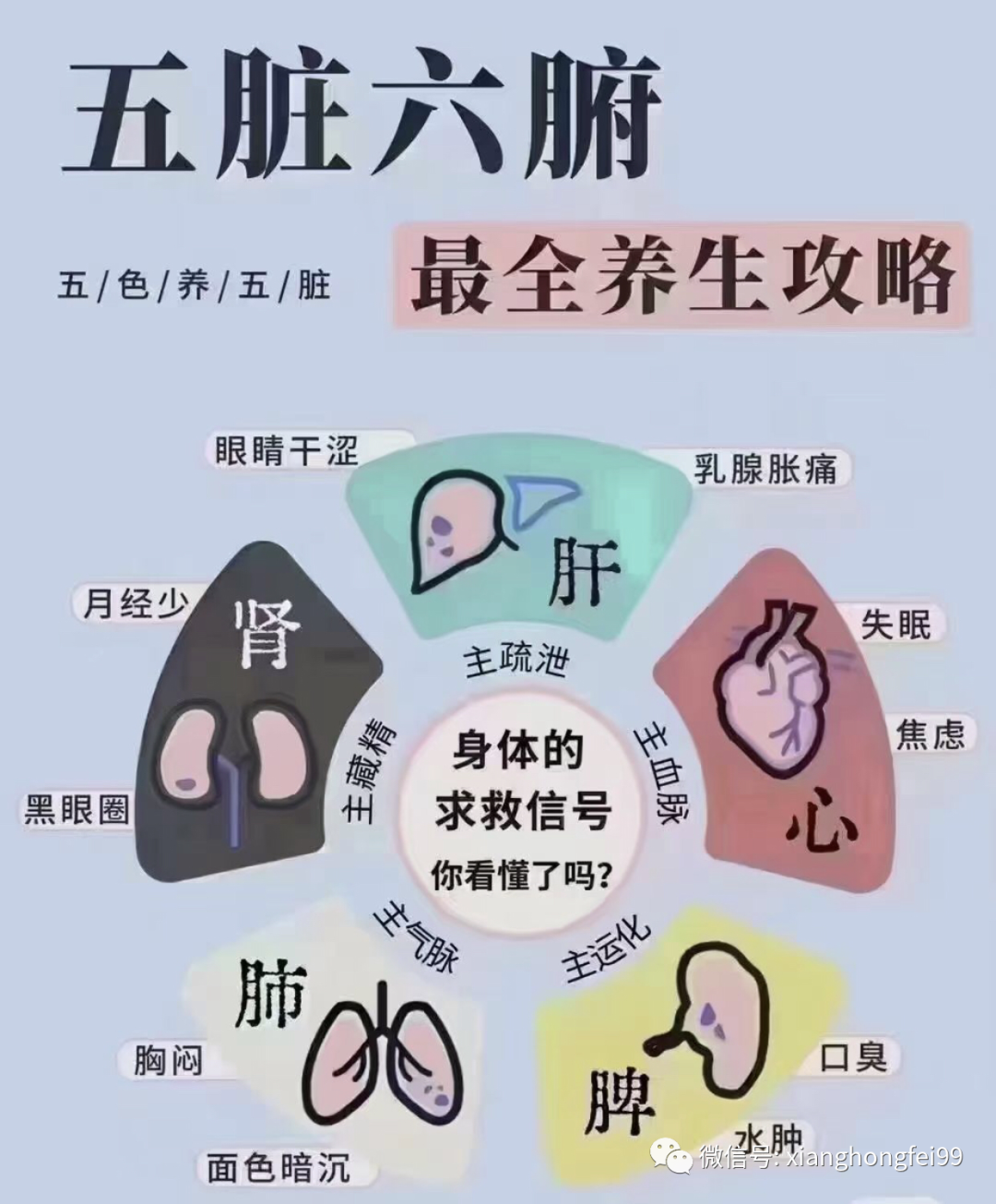

II. The Roles of the Five Organs and Six BowelsIn the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), there is a brilliant description of the status and interrelationships of the five organs and six bowels. It assigns titles to these organs, allowing them to play different roles, and the relationships between these roles vividly illustrate TCM’s understanding of organ relationships.The heart (xin) is the monarch’s organ, from which the spirit (shen) emerges. The term “monarch’s organ” means the “leader” that governs the other organs, and its importance is self-evident. From the perspective of character formation, the character for “heart” is the only one without the “moon” radical, indicating its uniqueness. It is important to note that in TCM, the “heart” does not refer solely to the anatomical heart but to the “hidden image” of the heart, which encompasses various phenomena expressed by the organ. The lung (fei) is the ministerial organ, responsible for regulating the body’s rhythms. The term “ministerial organ” refers to the prime minister, who is the emperor’s right-hand man, holding a high position among officials. The emperor does not engage in specific tasks; it is this minister who truly formulates strategies. “Regulating rhythms” means that when the lung functions well, the body can achieve harmony. The liver (gan) is the general’s organ, from which strategies emerge. The liver plays the role of a general strategizing in the command tent. If liver qi and liver blood are deficient, a person may easily become angry and irritable, and decisions made in such a state are often unwise. To utilize one’s intelligence, one must pay attention to this “general’s organ”. The spleen and stomach (piwei) are the granary organs, from which the five flavors emerge. Since the spleen and stomach are interrelated, they are often discussed together. In fact, the spleen has a special role as the “advisory organ”—the one that identifies problems and offers candid advice. “Knowing the surroundings” means being aware of the situation and reporting it to the central authority. The stomach serves as the granary manager, responsible for processing food and distributing nutrients to nourish the five organs and six bowels.

II. The Roles of the Five Organs and Six BowelsIn the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), there is a brilliant description of the status and interrelationships of the five organs and six bowels. It assigns titles to these organs, allowing them to play different roles, and the relationships between these roles vividly illustrate TCM’s understanding of organ relationships.The heart (xin) is the monarch’s organ, from which the spirit (shen) emerges. The term “monarch’s organ” means the “leader” that governs the other organs, and its importance is self-evident. From the perspective of character formation, the character for “heart” is the only one without the “moon” radical, indicating its uniqueness. It is important to note that in TCM, the “heart” does not refer solely to the anatomical heart but to the “hidden image” of the heart, which encompasses various phenomena expressed by the organ. The lung (fei) is the ministerial organ, responsible for regulating the body’s rhythms. The term “ministerial organ” refers to the prime minister, who is the emperor’s right-hand man, holding a high position among officials. The emperor does not engage in specific tasks; it is this minister who truly formulates strategies. “Regulating rhythms” means that when the lung functions well, the body can achieve harmony. The liver (gan) is the general’s organ, from which strategies emerge. The liver plays the role of a general strategizing in the command tent. If liver qi and liver blood are deficient, a person may easily become angry and irritable, and decisions made in such a state are often unwise. To utilize one’s intelligence, one must pay attention to this “general’s organ”. The spleen and stomach (piwei) are the granary organs, from which the five flavors emerge. Since the spleen and stomach are interrelated, they are often discussed together. In fact, the spleen has a special role as the “advisory organ”—the one that identifies problems and offers candid advice. “Knowing the surroundings” means being aware of the situation and reporting it to the central authority. The stomach serves as the granary manager, responsible for processing food and distributing nutrients to nourish the five organs and six bowels.

The kidney (shen) is the organ of strength, from which skills emerge. What does it mean to be the “organ of strength”? Compared to other organs, this role may seem less understood. Does this mean it is unimportant? On the contrary, it signifies the generation of strong vitality, providing the necessary energy.

The gallbladder (dan) is the organ of justice, from which decisions emerge. The “organ of justice” presides over fairness and decisive actions, akin to a modern-day judge. When gallbladder qi is strong, a person exhibits confidence and assertiveness; the idioms “timid as a mouse” and “bold as a lion” stem from this concept. The small intestine (xiao chang) is the organ of reception, from which transformation occurs. Its primary responsibilities are to “receive” and absorb the essence of grains and to “transform” food into nutrients that the body can absorb. The “organ of reception” is busy every day, merely serving as a channel; once it has “harvested,” it promptly distributes the nutrients, exemplifying diligence.  III. The Endless Connections The Huangdi Neijing describes the connections between the body’s meridians as “like a ring without end,” indicating that these connections are cyclical, with no beginning or end. The relationships between the organs are similarly interconnected. This leads to the origin of the saying “the liver and gallbladder reflect each other”—the relationship between the organs’ exterior and interior. The lung is connected to the large intestine: if lung qi is weak, the body’s ability to expel waste will be compromised, leading to what TCM calls “qi deficiency constipation.” If the large intestine does not function properly, it can also hinder lung qi, resulting in coughing and wheezing.

III. The Endless Connections The Huangdi Neijing describes the connections between the body’s meridians as “like a ring without end,” indicating that these connections are cyclical, with no beginning or end. The relationships between the organs are similarly interconnected. This leads to the origin of the saying “the liver and gallbladder reflect each other”—the relationship between the organs’ exterior and interior. The lung is connected to the large intestine: if lung qi is weak, the body’s ability to expel waste will be compromised, leading to what TCM calls “qi deficiency constipation.” If the large intestine does not function properly, it can also hinder lung qi, resulting in coughing and wheezing.

Conclusion: The human body is a fascinating “microcosm”; seemingly unrelated phenomena may have intrinsic, inseparable connections. This is also why TCM does not treat symptoms in isolation, such as “treating the head for headaches and the feet for foot pain.”