Many people have studied the Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica), and research on it has almost become a specialized academic discipline. My reflections on reading the Ben Cao Gang Mu are merely a small insight into this great work.

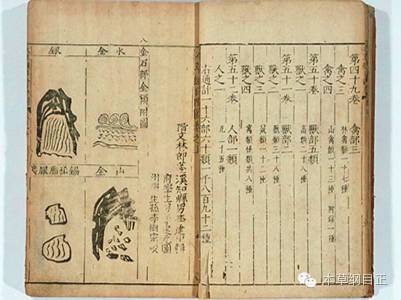

In the opening section of Li Shizhen‘s Ben Cao Gang Mu, the principles of drug classification are discussed, categorizing all substances into sixteen sections as the framework, and further subdividing them into sixty categories. This classification system is what gives the work its name, Ben Cao Gang Mu, reflecting a systematic approach. The first sections are categorized by water and fire, followed by earth, as water and fire are the origins of all things, and earth is the mother of all. Next, metal and stone are included, derived from earth. This forms four sections. Following this, grasses, grains, vegetables, fruits, and trees are categorized, from the minute to the massive, forming six sections. Lastly, insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and finally humans are included, from the lowly to the noble, completing the sixteen sections. Each section has further classifications, such as:

The ten categories of the grass section (mountain grasses, fragrant grasses, xi grasses, poisonous grasses, creeping grasses, water grasses, stone grasses, mosses, weeds, and named but unused herbs).

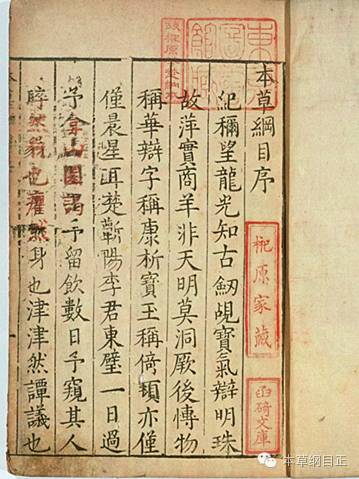

Li Shizhen (1518—1593) began compiling the Ben Cao Gang Mu in the thirty-first year of the Jiajing era (1552), with the first draft completed in the sixth year of the Wanli era (1578), followed by over ten years of revisions and three drafts. In the twenty-second year of Wanli (1593), Li Shizhen passed away. The work was officially published three years later in the twenty-fifth year of Wanli (1596). It is evident that he began writing the Ben Cao Gang Mu at the age of thirty-five, completed the first draft at sixty, and passed away at seventy-five, with the work published posthumously. This great work took nearly half a century to complete. What is regret? The author, who devoted his life to compiling this monumental work, did not see it published before his death; is this not the greatest regret? What is greatness? A person’s writings becoming a classic for future generations, a work unparalleled in history; is this not the greatest achievement?

From the initial draft of the Ben Cao Gang Mu to today, over four hundred thirty years have passed. We attempt to grasp some of Li Shizhen’s academic thoughts.

First, let’s look at the basic principles of drug classification in the Ben Cao Gang Mu. Water and fire are the origins of all things, and earth is the mother of all, hence the opening discusses water, fire, and earth, followed by metal and stone, as metals and stones come from earth. The ancients believed that water, fire, earth, metal, and wood are the elements that constitute all things. Tracing the origins of all things leads back to these five elements. Next, the discussion turns to plants, with the basic principle being “from the minute to the massive,” from small plants to large ones, categorized as grasses, grains, vegetables, fruits, and trees. Following this, animals are discussed, with the principle being “from the lowly to the noble,” from lower animals to higher ones, categorized as insects, scales, shells, birds, beasts, and humans. Prior to the Ming dynasty, materia medica texts generally followed the three-tier classification system of the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing (Divine Farmer’s Classic of Materia Medica), which divides drugs into three grades: upper, middle, and lower. According to the Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing:

Upper medicines, one hundred twenty types, are the sovereign, primarily nourishing life and responding to heaven. They are non-toxic, can be taken frequently and for long periods without harm. Those wishing to lighten the body, enhance energy, and prolong life should refer to the upper classics.

Middle medicines, one hundred twenty types, are the minister, primarily nourishing the nature and responding to humanity. They may be toxic or non-toxic, to be used judiciously. Those wishing to prevent illness and replenish weakness should refer to the middle classics.

Lower medicines, one hundred twenty-five types, are the assistant and envoy, primarily treating diseases and responding to the earth. They are often toxic and should not be taken for long. Those wishing to eliminate cold, heat, and evil qi, break accumulations, and cure diseases should refer to the lower classics.

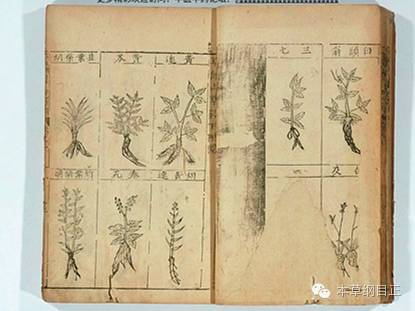

The three-tier classification system evidently has shortcomings in precision and practicality, which, in modern terms, can be deemed unscientific. By the time of Li Shizhen, he completely abandoned this millennia-old classification method and established a unique biological classification system. He clearly recognized the concept of “natural hierarchy.” His classification method reflects the evolution from non-living to living, from simple to complex, from lower to higher, and from aquatic to terrestrial life, generally aligning with the objective laws of natural development. We find that over four hundred years ago, Li Shizhen’s classification of medicinal plants bears many similarities to modern classifications. His meticulous observations, in-depth research, and precise analyses of medicinal plants are evident. The Swedish botanist Linnaeus, regarded as the father of Western botany, classified plants into two categories and twenty-four classes, with his representative work Systema Naturae published in 1735, merely twelve pages long, and 139 years later than the Ben Cao Gang Mu, with much simpler content. By Linnaeus’s time, the Ben Cao Gang Mu had already reached Europe, and it is said that Linnaeus was somewhat familiar with it.

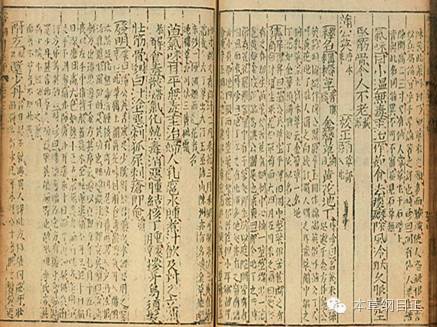

Next, let’s examine the variety of species recorded in the Ben Cao Gang Mu, which is quite complex, with some exceeding modern understanding. For example:

In the water section, there are records of rainwater, dew, sweet dew, winter frost, wax snow, hail, well water, and water for sharpening knives; in the fire section, there are records of yin fire, yang fire, charcoal fire, moxa fire, fire needles, lamp fire, and candle ashes; in the earth section, there are understandable entries like chalk, sweet earth, red earth, yellow earth, fu long gan (dragon liver), and bai cao shuang (herb frost), but also bizarre entries like soil from under shoes and dust from a widow’s bed. The section on tools and utensils includes records of sweat shirts, filial shirts, headscarves, straw sandals, fishing nets, steamers, and pot lids; in the human section, there are records of hair, nails, teeth, human bones, and human placenta, as well as human excretions like ren zhong huang (human bile), urine, and breast milk, along with many other strange categories. After all, this is a work from over four hundred years ago, influenced by the limitations of contemporary understanding of nature and superstitions, containing some remnants of outdated beliefs, which is an undeniable mark of its time.

To observe, collect, and verify medicinal specimens, Li Shizhen first conducted investigations in his hometown of Qizhou, and later traveled extensively, covering over twenty thousand li, visiting places such as Hubei, Jiangxi, Jiangsu, and Anhui. Later generations wrote poetry reflecting his extensive travels and interviews, describing his life of exploration. The Ben Cao Gang Mu records 1892 types of medicinal substances, which correspond to 1892 types of natural products. Under the vast sky, Li Shizhen first felt the ancient changes of the sun, moon, and stars, the unpredictable shifts of fog, rain, and thunder, as he visited mountains and fields, traversed rivers and lakes, witnessing the flourishing of grasses, grains, vegetables, fruits, and trees, and the playful reproduction of insects, scales, shells, birds, and beasts. Everything in nature, in his eyes, possessed a unique quality—medicinal properties; everything he surveyed in the world was medicine!

This is the material view, cognitive view, and medicinal view of ancient medical scholars that I have gleaned from reading the Ben Cao Gang Mu.

Modern pharmacology is generally defined as the science that studies the interactions between drugs and the body. According to this definition, drugs and the body interact; on one hand, drugs act on the body, producing pharmacological effects such as therapeutic effects and adverse reactions; on the other hand, the drugs entering the body are also acted upon by the body, a process known as metabolism, transformation, or digestion, and both processes occur simultaneously. Let’s shift the concept: instead of studying the interaction between “drugs” and our “body,” we study the interaction between “various natural substances” and our “body.” This aligns perfectly with the material view, cognitive view, and medicinal view of the Ben Cao Gang Mu. Understanding the world from the perspective of pharmacology means studying the interactions of various substances in our surrounding world with our body, the effects they produce, and how these substances are metabolized and digested by our body. Our studies of drugs and toxins, environmental ecology, culinary practices, tea and alcohol culture, agriculture and animal husbandry, etc., all involve the interactions of substances with the body, right? From studying the classic pharmacology of the Ben Cao Gang Mu to the more precise modern pharmacology, we gain a new perspective on studying the world from a pharmacological angle.

Therefore, the ultimate viewpoint of the Ben Cao Gang Mu should be: the world is medicine.