Click the blue text

Follow us

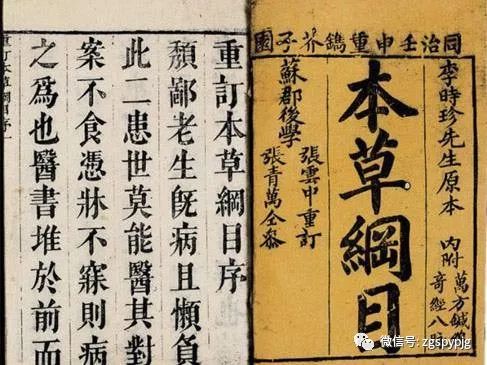

The term “Materia Medica” first appeared in the Book of Han by Ban Gu during the Eastern Han Dynasty, stating: “… all dismissed, the diviners, envoys, assistants, and over seventy Materia Medica officials all returned home.” Here, the term “Materia Medica” refers to medicines and prescriptions, hence later generations often use “Materia Medica” to replace the term for medicines. This is because in the use of animal, plant, and mineral medicines, herbs are predominant and considered fundamental. Subsequently, later medical scholars often named their works on medicines as “Materia Medica,” such as the “Shennong Bencao Jing” (Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica), “Xinxiu Bencao” (Newly Revised Materia Medica), and “Zhenglei Bencao” (Classified Materia Medica). Among a series of Materia Medica works, Li Shizhen’s “Bencao Gangmu” (Compendium of Materia Medica) from the Ming Dynasty holds epoch-making significance and is a milestone work that has been renowned throughout history.

“Bencao Gangmu” absorbed the essence of previous Materia Medica works, corrected past errors as much as possible, supplemented deficiencies, and made many important discoveries and breakthroughs. It is the most systematic, complete, and scientific medical work in China up to the 16th century. The rich content of the book involves knowledge from various disciplines, including language, literature, history, astronomy, geography, geology, mining, biology, and chemistry, making it a comprehensive work of natural history. The renowned British scholar Joseph Needham (1900-1995) highly praised Li Shizhen’s “Bencao Gangmu” in his book “Science and Civilisation in China,” stating: “Without a doubt, the greatest scientific achievement of the Ming Dynasty is Li Shizhen’s unparalleled ‘Bencao Gangmu.'” Darwin praised it as “China’s encyclopedia.”

Regarding the origin of the title “Bencao Gangmu,” some believe it was inspired by Zhu Xi’s “Tongjian Gangmu” from the Southern Song Dynasty. Legend has it that after completing “Bencao Gangmu,” Li Shizhen had not yet determined the title. One day, after returning from a medical visit, he habitually sat at his desk. When he saw the “Tongjian Gangmu” he had read the day before still placed on the table, he suddenly had an idea and immediately picked up his brush, dipped it in ink, and wrote the four powerful characters “Bencao Gangmu” on the pristine cover of the manuscript. He looked at it excitedly and said to himself, “Yes, it shall be called ‘Bencao Gangmu!'” However, I believe this account is not credible. Li Shizhen’s compilation of the Materia Medica was structured as “to outline and categorize,” and he was clear about the framework of his work from the beginning. The title “Bencao Gangmu” was already determined in Li Shizhen’s mind.

Many people are familiar with “Bencao Gangmu,” and its academic value is widely recognized. The hardships and twists surrounding its publication are also worth exploring and understanding.

The Jinling Edition – The Source of a Timeless Work

Wang Shizhen and the “Bencao Gangmu”

Li Shizhen endured great hardships, revising his manuscript three times, and finally completed this monumental work, which was no easy feat. Equally challenging was the publication of “Bencao Gangmu,” which also went through many twists and turns. Regrettably, Li Shizhen himself never saw the publication of the manuscript he had devoted most of his life to.

Li Shizhen was a person with grand ambitions. His practice of medicine, gathering herbs, and studying were not merely to improve his medical skills or teach disciples; he aimed to disseminate practical and correct medical knowledge to more people and pass it on to future generations, allowing more people to save lives. During the compilation process, Li Shizhen constantly considered the issue of publication. He knew that he was merely a person relying on medicine for a living, and in places like Qizhou, Huangzhou, and Wuchang, it was impossible to publish such a monumental work relying solely on personal efforts. Therefore, he decided to go to Nanjing to seek a solution.

Despite his advanced age and declining health, in 1580 (the eighth year of the Wanli era), he set off from his hometown, traveling downstream to Jinling.

Jinling, now Nanjing, was once the capital of the Ming Dynasty and a place where scholars gathered and people from various regions coexisted. After the establishment of the feudal dynasty by the Ming rulers, they adopted a policy of “self-reliance” and encouraged the people to develop production. The rapid development of agriculture promoted changes in the social economy, leading to a prosperous situation in commerce and industry. At that time, it was the largest city in China, with the highest population, and also the largest city in the world. With economic development, the Ming Dynasty’s papermaking and printing industries had made significant progress, and movable type printing was widely used. Many wealthy booksellers used copper movable type to publish various books. At this time, Jinling had become the center of the publishing industry in the country, a gathering place for booksellers. Historical records indicate that there were over ninety bookstores in Jinling at that time, far exceeding Beijing. Many medical books were published, such as the “Complete Good Prescriptions for Women” published by Tang’s Fuchuntang, “The Great Achievement of Acupuncture and Moxibustion” published by Sanduo Zhai, and “Newly Engraved and Supplemented Ancient and Modern Medical Mirror” published by Zhou Tinghuai. Ming scholar Hu Yinglin stated: “Wuhui and Jinling are renowned for their literature, with the most published works and a gathering of extensive collections of large books.”

Li Shizhen chose to come to Jinling, hoping to print and publish “Bencao Gangmu,” believing that such a monumental work could only be undertaken by the booksellers or publishing houses in Jinling. This indicates that although Li Shizhen practiced medicine and gathered herbs in Hubei, he was well aware of the affairs of the world. However, things did not go as Li Shizhen wished. At that time, most booksellers were keen on printing works related to “Cheng-Zhu Neo-Confucianism” and other feudal moralistic works for their own entertainment, completely ignoring Li’s immortal masterpiece aimed at saving lives. Perhaps they regarded the art of medicine as trivial and did not take it seriously. Therefore, despite Li Shizhen’s years of wandering in Jinling, he was unable to find a suitable bookstore to collaborate with, causing the publication of “Bencao Gangmu” to be forced to halt.

Finally, through the unremitting efforts of Li Shizhen and his son, “Bencao Gangmu” was eventually published in Jinling, which is the version we see today. However, its publication was closely related to a famous figure of the Ming Dynasty, Wang Shizhen. It can be said that without Wang Shizhen, there would be no Jinling edition of “Bencao Gangmu” as we see today.

Wang Shizhen, styled Yuanmei, also known as Fengzhou and Yanzhou Mountain Man, was born on the fifth day of the eleventh month in the fifth year of the Ming Jiajing era (December 8, 1526) and died on the twenty-seventh day of the eleventh month in the eighteenth year of the Ming Wanli era (December 23, 1590). He was from Taicang, Suzhou Prefecture, in the southern Jiangsu province. At seventeen, he passed the xiucai examination, at eighteen, he became a juren, and at twenty-two, he became a jinshi. He held various positions, including Left Minister of the Dali Temple, Deputy Minister of Justice, and Governor of Qingzhou in Shandong, among others. During the Wanli period, he served as the Inspector of Hubei, the Right Minister of Guangxi, and the Governor of Yunyang. Later, due to conflicts with Zhang Juzheng, he was dismissed and returned to his hometown. After Zhang Juzheng’s death, Wang Shizhen was reinstated as the Governor of Yingtian Prefecture and later became the Minister of Justice in Nanjing, eventually passing away with the title of Taizi Shaobao. Wang Shizhen was known as one of the “Seven Sons of the Later Period” along with Li Panlong, Xu Zhongxing, Liang Youyu, Zong Chen, Xie Zhen, and Wu Guolun. After Li Panlong’s death, Wang Shizhen led the literary world for twenty years, authoring works such as “Four Volumes of Yanzhou Mountain Man” and “Yanshan Tang Collection.”

During his time in Jinling, Li Shizhen not only diagnosed patients but also continued to collect materials and identify herbs, constantly improving the manuscript while pondering how to publish it. Li Shizhen’s compilation of the manuscript drew from the bibliographies of ancient and modern texts, including the “Three Capitals Ode” by Zuo Si. Zuo Si, who was not handsome and came from a humble background, spent ten years crafting the “Three Capitals Ode,” which was not valued by his contemporaries. The highly regarded Emperor Fu Mi wrote a preface to promote it, leading to its widespread copying and making “Luoyang paper expensive.” Inspired by this, Li Shizhen believed he needed to find someone who could make “Bencao Gangmu” equally popular. The famous literary figure Wang Shizhen was the only choice. Thus, in the eighth year of the Wanli era (1580), Li Shizhen, filled with hope, took a boat to Taicang in Jiangsu to visit Wang Shizhen. Regarding this meeting, Wang Shizhen’s preface to “Bencao Gangmu” states: “Mr. Li from Qizhou visited me one day at Yanshan Garden, staying for several days. I observed him; he had a refined appearance, a slender figure, and spoke eloquently, truly a unique individual. He had several dozen volumes of ‘Bencao Gangmu.'”

This meeting between Li and Wang was not smooth. From Wang’s use of the term “visited me,” it is evident that despite Li Shizhen being sixty-three and Wang Shizhen fifty-five, Wang did not regard Li Shizhen with much importance. Fortunately, Li Shizhen’s complexion was healthy, and his demeanor was refined, making a good first impression, which led Wang to invite him to stay for several days. This allowed Li Shizhen the opportunity to introduce his manuscript. However, Wang Shizhen did not have the time or energy to read “Bencao Gangmu” in detail at that time, as he was busy with another significant matter, namely the transformation of the Taoist master Tanyangzi. According to Qian Daxin’s “Chronicle of Yanzhou Mountain Man,” in the eighth year of the Wanli era, he began visiting Tanyangzi to seek the Dao, claiming to be a disciple… In September, Tanyangzi passed away, and Wang wrote a biography in his honor.

Perhaps another reason is that Wang Shizhen was then infatuated with Taoist practices for health and immortality, and he resented Li Shizhen’s criticisms of alchemists in “Bencao Gangmu,” leading to ideological conflicts between the two. Thus, Wang Shizhen described Li Shizhen’s visit in his “Yanzhou Continuation” with a hint of sarcasm: “On the evening Mr. Li from Qizhou visited, it was also the time of the ascension of the immortal master. He then took out the ‘Bencao’ he had revised and jokingly gifted it to me.”

Li Shizhen slightly adjusted the trees by the pond and saw the immortal riding a dragon ascend; he then took out the book from the blue bag, seemingly seeking the preface from the mysterious master.

Hua Yang’s true immortal was about to ascend, mistakenly delaying the Materia Medica by ten years; how could it be better to just attach the shoes of the virtuous man and ascend to the ninth heaven?

From various texts, it is evident that Wang Shizhen did not regard Li Shizhen and his manuscript with much importance. However, he ultimately agreed to write the preface. The phrase in the preface, “I am currently writing ‘Yanzhou Zhi Yan,'” suggests that the first draft of this preface was likely completed during their initial meeting, but for some reason, it was not finalized until ten years later. At that time, Wang Shizhen was serving as the Minister of Justice in Nanjing, with graying hair and declining health. Additionally, his brother Wang Shimao had passed away prematurely in the sixteenth year of the Wanli era (1588), causing him great sorrow; he was also unjustly criticized and had previously requested retirement without success. At this time, he once again submitted a request for retirement. Upholding his previous promise, he slightly revised the earlier preface and handed it to Li Shizhen on the day of the Lantern Festival in the spring of the eighteenth year of the Wanli era (1590).

There are various theories regarding why Wang Shizhen delayed writing the preface. Some believe it was because Li Shizhen could not offer a high fee, which is purely speculative and unfounded. However, it is generally believed that Wang Shizhen had a rather difficult ten years and, due to his resignation and return home, was in a bad mood and reluctant to revise and improve the preface. This is supported by textual records. Another theory suggests that although Wang Shizhen was a literary figure, he was well-versed in medical principles. He discovered many errors and deficiencies in the manuscript of “Bencao Gangmu” that required significant effort to revise and supplement, and he did not want to rush to publish it. Li Shizhen was convinced by this, and after spending another ten years on rigorous editing, he once again approached Wang Shizhen, who then recognized it. Thus, Wang Shizhen gladly wrote the preface and handed it to Li Shizhen. According to this theory, the “Bencao Gangmu” we see today is not only due to Wang Shizhen’s preface but also thanks to his feedback on the manuscript, which enriched and improved its content, reaching a new height.

Wang Shizhen evaluated in the preface: “From ancient texts to legends, everything related is thoroughly collected… the essence of nature and reason, the comprehensive records of things, the secret records of emperors, and the treasures of the people.” This preface provides a high yet accurate evaluation of the book, calling it “the essence of nature and reason,” indicating profound philosophy; calling it “the comprehensive records of things,” is akin to saying it is an encyclopedia. His preface added a significant touch to the publication of the Jinling edition of “Bencao Gangmu” and played a promoting role.

Due to the outstanding content and Wang Shizhen’s praise in the preface, after many twists and turns, Li Shizhen finally contacted the Jinling bookseller Hu Chenglong in the eighteenth year of Wanli (1590). After reading the manuscript of “Bencao Gangmu,” Hu believed it to be an outstanding work of great collectible value and decided to fund its printing. By this time, Li Shizhen was nearing seventy, having suffered from accumulated labor and illness. He returned to his hometown in Qizhou, entrusting the printing matters to his eldest son, Jianzhong. In the twenty-first year of Wanli (1593), the book was officially published in Nanjing, and three years later (1596), it was officially released, which is the original version of “Bencao Gangmu” – the Jinling edition. From then on, the Jinling edition became the source of various versions of “Bencao Gangmu” in later generations, best reflecting its original appearance. Once published, the book quickly spread throughout the country, becoming a must-have book for all social classes.

The Jinling Edition of “Bencao Gangmu”

The “One Ancestor, Three Branches” Versions and Dissemination of “Bencao Gangmu”

It is impossible to ascertain how many copies of the Jinling edition were published at that time, but according to verified information, there are currently seven existing versions, of which five are held abroad, and only two are in China, located in the library of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences in Beijing and the Shanghai Library. Among the five versions abroad, three are in Japan, held in the Japanese Cabinet Library, the Kyoto Gifting Botanical Garden’s Omori Library, and Dr. Itō Taketaro’s collection; one is in Germany, held in the Royal Library of Berlin, which was obtained from China over 200 years ago by a Dutchman, Georgt Eberhard Rumpt; and one is in the United States, held in the Library of Congress, which was transmitted to the United States during the early stages of the Anti-Japanese War.

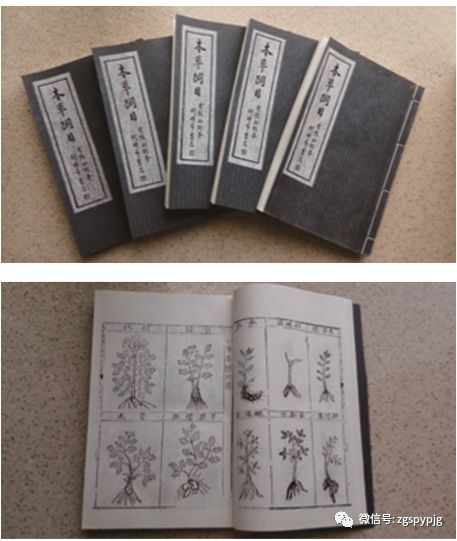

Due to the rarity and limited number of the Jinling edition of “Bencao Gangmu,” after its publication, several versions based on the Jinling edition emerged, forming different version systems of “Bencao Gangmu.” These can be broadly divided into four categories, with textual differences among the various versions, but the most significant difference lies in the medicinal illustrations.

(1) The Jinling Edition is the first edition of “Bencao Gangmu,” also known as the ancestral edition, published in 1593 by Hu Chenglong in Jinling (now Nanjing). The book includes two volumes of medicinal illustrations, totaling 1109 images (depicting 1129 types of medicines), of which 98 images are transcribed from the “Zhenglei Bencao,” while the majority of the other images were redrawn, compiled by Li Shizhen’s son Li Jianzhong, and illustrated by Li Jianyuan and Li Jianmu. Although they are relatively crude and the engraving work is lacking, they adequately reflect Li Shizhen’s academic insights. Currently, the Shanghai Science and Technology Publishing House has published a facsimile of the Jinling edition based on the collection of the Shanghai Library; the Ancient Chinese Medicine Publishing House has published a horizontal lead-printed version based on the collection of the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences; in 1998, Huaxia Publishing House published a corrected version of “Bencao Gangmu” by Liu Hengru and Liu Shanyong, which is based on the Jinling edition. In 2011, the original woodblock edition of “Bencao Gangmu” (1593, published by Hu Chenglong in Jinling) and the “Huangdi Neijing” (1339, published by Hu’s Ancient Forest Bookstore) were jointly included in the “World Memory Register,” which was approved at the tenth meeting of the International Advisory Committee of the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme held in Manchester, UK, from May 23 to 26 that year.

(2) The Jiangxi Edition was reprinted in 1603 by Xia Liangxin and Zhang Dingsi in Nanchang, Jiangxi, during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, serving as the base text for various versions of “Bencao Gangmu.” This edition retains the basic appearance of the Jinling edition in terms of text and medicinal illustrations, but with some changes. From 1977 to 1981, the People’s Health Publishing House published a corrected version by Liu Hengru, with the first three volumes based on the Jiangxi edition and the fourth volume referencing the Jinling edition, containing 12,600 correction notes. This corrected version has been reprinted multiple times.

(3) The Qian Weiqi Edition was reprinted in 1640 by Qian Weiqi, published in Hangzhou, with medicinal illustrations redrawn by Lu Zhe, divided into three volumes with 1110 images. From 1640 to 1885, the reprints of “Bencao Gangmu” were primarily based on this edition, with numerous printings and significant influence. However, while the medicinal illustrations were visually appealing, many were distorted and did not accurately reflect the original intent of “Bencao Gangmu.”

(4) The Zhang Shaotang Edition was reprinted in 1885 by Zhang Shaotang, published in Nanjing, with the text referencing both the Jiangxi and Qian editions, and the medicinal illustrations redrawn by Xu Gongfu. It included some illustrations from the “Jiu Huang Bencao” and the “Plant Names and Realities Examination.” Although the illustrations were more refined, they were no longer the original illustrations from Li Shizhen’s “Bencao Gangmu.” This edition was finely crafted and aesthetically pleasing, and the vast majority of reprints of “Bencao Gangmu” from the late Qing to the early Republic of China were based on the Zhang Shaotang edition.

Shortly after the publication of “Bencao Gangmu,” it spread to Japan, Korea, and various Western countries due to commercial trade and the visits of scholars or missionaries, and it was subsequently translated into various languages, including Korean, Japanese, English, French, German, Russian, and Latin. Its dissemination in the East and West has had a profound impact on the development of pharmacology worldwide. The reason it has been pursued by foreign luminaries for centuries is primarily due to the inexhaustible essence and wisdom it contains, revealing the scientific laws and essence of the natural world, ensuring its enduring brilliance in the history of world science.

The Influence of “Bencao Gangmu” on Future Generations

The publication of “Bencao Gangmu” played a pivotal role in the development of Materia Medica studies, and the flourishing of Materia Medica research during the Ming and Qing dynasties is closely related to it. During this period, a number of Materia Medica works emerged, many of which were related to “Bencao Gangmu.” Particularly in the Qing Dynasty, many simplified Materia Medica readings based on “Bencao Gangmu” appeared, such as during the Kangxi period, Cai Liexian compiled “Bencao Wanfang Zhenxian,” categorizing the prescriptions in “Bencao Gangmu” according to the diseases treated into seven parts and 105 sections, with the original book’s volume and page numbers noted, becoming the origin of the index for the prescriptions in “Bencao Gangmu.” Subsequently, there were works like Cao Shengyan’s “Bencao Gangmu Wanfang Leizuan,” Song Mu’s “Wanfang Leizuan,” and Zhu Ming’s “Gangmu Wanfang Quanshu.” There were also compilations focusing on specific content of “Bencao Gangmu” for different research needs, such as Zhang Rui’s “Guidelines for Repairs,” Geng Shizhen’s “Bencao Gangmu Shiming,” and Jiang Hongmo’s “Zhengzhi Yaoli.” It can be said that most Materia Medica works in the Qing Dynasty were compiled based on “Bencao Gangmu,” but aside from Zhao Xueming’s “Bencao Gangmu Shiyi,” which corrected and supplemented “Bencao Gangmu,” most Materia Medica literature lacked innovation, which is a shortcoming of Qing Dynasty Materia Medica.

Modern research on Materia Medica also cannot be separated from the foundation laid by “Bencao Gangmu.” Research on “Bencao Gangmu” remains a hot topic in the field of modern Chinese medicine, with various corrected versions being published; various theories of medicinal properties or clinically practical Materia Medica works based on “Bencao Gangmu” have emerged, and research papers related to “Bencao Gangmu” are published in hundreds of different journals each year. The contemporary work “Zhonghua Bencao,” hailed as the “new ‘Bencao Gangmu,'” includes most of the content from “Bencao Gangmu.” Scholars studying “Bencao Gangmu” are not limited to the field of Chinese medicine; botanists, biologists, zoologists, mineralogists, chemists, as well as philosophers, historians, thinkers, and literary figures have shown great interest in it. Why does a single “Bencao Gangmu” possess such vitality and profound influence? The key lies in its profound revelation of the laws and essence of “Materia Medica” and other fields in the natural world, accurately predicting its future, and continuously being validated by human practice. It can be anticipated that “Bencao Gangmu” will endure for millennia, benefiting humanity.

Source: Chen Renshou. Qing Nang [M]. Beijing: China Medical Science and Technology Press, 2016: 04-14.