The Jilin Provincial Association for Science and Technology is dedicated to spreading scientific ideas, sharing technological lifestyles, and improving public scientific literacy.

Ginseng, known as Ren Shen (人参, Panax ginseng C. A. Mey.), is the dried root and rhizome of the Araliaceae family plant. It is harvested in the autumn, cleaned, and then sun-dried or dried in an oven. Cultivated ginseng is commonly referred to as “garden ginseng”; ginseng that grows naturally in the wild is called “wild ginseng” or “seed ginseng”. The 2020 edition of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia records that ginseng has a sweet and slightly bitter taste, is slightly warm in nature, and enters the spleen, lung, heart, and kidney meridians. It is known for its ability to greatly replenish vital energy, stabilize the pulse, strengthen the spleen and lung, generate fluids and nourish the blood, calm the mind, and enhance intelligence. It is used to treat conditions such as deficiency leading to collapse, cold limbs with weak pulse, spleen deficiency with poor appetite, lung deficiency with cough and wheezing, fluid damage with thirst, internal heat with excessive thirst, qi and blood deficiency, prolonged illness with weakness, palpitations, insomnia, impotence, and cold in the uterus.

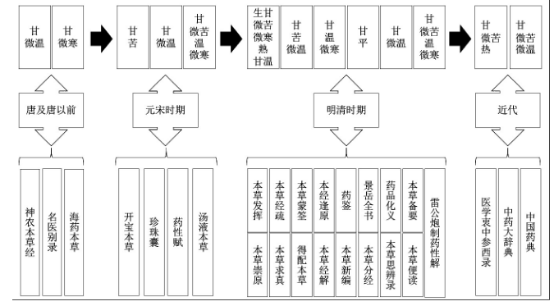

Ginseng is a commonly used qi-tonifying herb in clinical practice and is regarded as the “first essential medicine for treating deficiency and internal injury”. Ginseng is recorded in the Han Dynasty’s Shennong Bencao Jing, classified into three grades: superior, medium, and inferior, with ginseng being the superior grade. It is described as “sweet and slightly cold, primarily tonifying the five organs, calming the spirit, stabilizing the soul, stopping palpitations, expelling evil qi, improving vision, and enhancing intelligence. Long-term use promotes longevity and lightness of body.” The Ming Yi Bie Lu from the late Han Dynasty states that it is “slightly warm, treating cold in the intestines and stomach, abdominal distension and pain, chest and flank fullness, cholera with vomiting, regulating the middle, stopping excessive thirst, promoting blood circulation, and breaking up accumulations, preventing forgetfulness.” The Hai Yao Ben Cao from the Tang Dynasty states that it is “sweet and slightly warm, benefiting the abdomen and waist, aiding digestion, nourishing the organs, tonifying qi, calming the spirit, stopping vomiting, regulating the pulse, expelling phlegm, and alleviating irritability and sourness.” The Zhen Zhu Nang from the Song Dynasty states that it is “sweet and bitter, nourishing blood, tonifying stomach qi, and draining heart fire.” The Yao Xing Fu from the Yuan Dynasty states that it is “sweet and warm, stopping thirst and generating fluids, harmonizing the middle and benefiting vital energy; it can be taken for lung cold but should be avoided for lung heat.” The Tang Ye Ben Cao states that it is “sweet, slightly bitter, warm, and slightly cold. Its sweet and warm taste regulates the middle and benefits qi, tonifying the lung’s yang and draining the lung’s yin.” The Jing Yue Quan Shu from the Ming Dynasty states that it is “sweet, slightly bitter, and slightly warm. It can tonify both qi and blood. For those with depleted yang qi, it can restore them to a state of vitality; for those with collapsed yin blood, it can revive them after a rupture. Its strong qi does not cause bitterness, thus it can stabilize qi; its sweet and pure taste allows it to tonify blood.” The Ben Cao Qiu Zhen from the Qing Dynasty states that it “has a neutral nature, neither cold nor dry. It primarily enters the lung and also the spleen. Its shape resembles a human, and it is the leader among herbs, capable of restoring lung vital energy from the brink of collapse.” The Ben Cao Bei Yao states that it is “sweet, slightly bitter, slightly cold when raw, and sweet and warm when cooked. It greatly replenishes vital energy and drains fire. It significantly replenishes lung vital energy, brightens the eyes, enhances intelligence, boosts spirit, calms palpitations, expels evil fire, and strengthens righteous qi. Thus, the heart and liver are calmed, and palpitations are settled. It alleviates thirst and drains fire, thus relieving irritability and stopping thirst.” The five organs belong to yin, and being slightly cold also belongs to yin; ginseng’s sweet and slightly cold nature is a yin-nourishing product and is used to tonify yin; fluids belong to yin, thus it can generate fluids.

Historical Evolution of Ginseng’s Properties[1]

Historical Evolution of Ginseng’s Properties[1]

Throughout different historical periods, there have been various viewpoints regarding the medicinal properties of ginseng, such as the slightly cold theory, warm nature theory, raw cool and cooked warm theory, and neutral nature theory. These perspectives have coexisted since the Tang and Song Dynasties. Each viewpoint has its reasonable components but also its shortcomings; overall, it remains a process of inheritance and development. The emergence of various theories on medicinal properties can be summarized by the famous TCM scholar Professor Ye Xianchun in four sentences: “Ginseng was not named in the Zhou and Qin Dynasties; the ginseng of the Eastern Han is not the same as today’s product; ginseng was used interchangeably in the Liang Dynasty; and it was only in the Ming and Qing Dynasties that ginseng was clearly differentiated”[2]. Initially, the ginseng used in prescriptions was likely the Shanxi Shangdang ginseng, which was indeed an Araliaceae plant, but due to overharvesting, it became extinct. Therefore, since the Qing Dynasty, Liao ginseng (Northeast ginseng) and Korean ginseng have gradually replaced Shanxi Shangdang ginseng as the authentic medicinal material. Although ancient Shanxi Shangdang ginseng, Liao ginseng, and Korean ginseng are all Araliaceae plants and have similar effects, there may still be certain differences in efficacy and properties.As the “King of Herbs”, ginseng’s medicinal properties are widely debated. If a normal person takes ginseng for an extended period or improperly, they may experience a series of side effects such as elevated blood pressure, nosebleeds, mental excitement, restlessness, and increased body temperature, known as “ginseng abuse syndrome”[3]. Therefore, modern practices often involve processing ginseng to reduce its warming and drying nature. Processed ginseng products are made from fresh ginseng, which is washed and then subjected to various processing techniques to create distinctive products. Currently, commercially available processed ginseng products include fresh ginseng that is cleaned, sun-dried, or dried at 40-50°C, known as “raw sun-dried ginseng”; fresh ginseng with roots and fibrous roots removed, steamed, and dried, known as “red ginseng”; and fresh ginseng that is freeze-dried, known as “freeze-dried ginseng” or “active ginseng”. The Ming Dynasty physician Li Shizhen stated in the Bencao Gangmu that ginseng “is cool when raw and warm when cooked”[4], clearly indicating that processing can alter ginseng’s medicinal properties. Modern systematic studies on ginseng and its various processed products have also found that some components undergo transformation during processing, producing new chemical constituents, and the ratios of these components change, which may be the material basis for the differences in pharmacology and properties between ginseng and its processed products[5].The nature of ginseng, whether cold, warm, or neutral, reflects both the evolution of varieties and the academic thoughts of physicians; however, its status as the “King of Herbs” remains unchanged. It is hoped that by learning from the advanced experiences of ancient practitioners and applying modern technology, we can further explore the medicinal properties and effects of ginseng, providing more insights for clinical prescription and medication.

| References

[1] Ren Guoqing, Dou Deqiang. Investigation of the Medicinal Properties of Ginseng-Related Chinese Medicines [J]. Ginseng Research, 2018, 30(6): 39-43.

[2] Ye Xianchun. The Evolution of Ginseng [J]. Research on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1982(12): 35-36.

[3] Lin Lijuan, Li Shuping. Analysis of “Ginseng Abuse Syndrome” [J]. Modern Distance Education of Chinese Medicine, 2009, 7(10): 223-224.

[4] Li Shizhen. Bencao Gangmu [M]. Beijing: Huaxia Publishing House, 2002: 490.

[5] Yu Qingtai. Research on the Evaluation of Warming and Drying Properties of Different Processed Ginseng Products [J]. Straits Pharmacy, 2018, 30(4): 45-47.

Author

Qi Bin, Professor at Changchun University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Master’s supervisor. Mainly engaged in research on quality standards of Chinese medicinal materials and slices, as well as the processing mechanisms and material basis of authentic medicinal materials in Jilin Province.

Zhang He, Associate Researcher at the Affiliated Hospital of Changchun University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Master’s supervisor. Mainly engaged in research on the active mechanisms of effective components in Chinese medicine and product development.

The platform content includes original, edited, and reprinted materials.

The platform content includes original, edited, and reprinted materials.

We respect originality: 1. All reprinted content is marked with the source; if the source cannot be found despite efforts, it is marked as “reprinted from the internet”. If there are omissions, the original author is welcome to contact us for attribution or deletion; 2. Any work marked “no reprinting allowed” will not be reprinted; 3. We reserve the right to appeal, report, take legal action, and expose malicious and false reports.