The culture of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has a long history and profound depth. The magical charm of TCM lies not only in its actual therapeutic effects but also in its rich cultural heritage, which is closely related to traditional culture.

1. Legends of the Origin of TCM

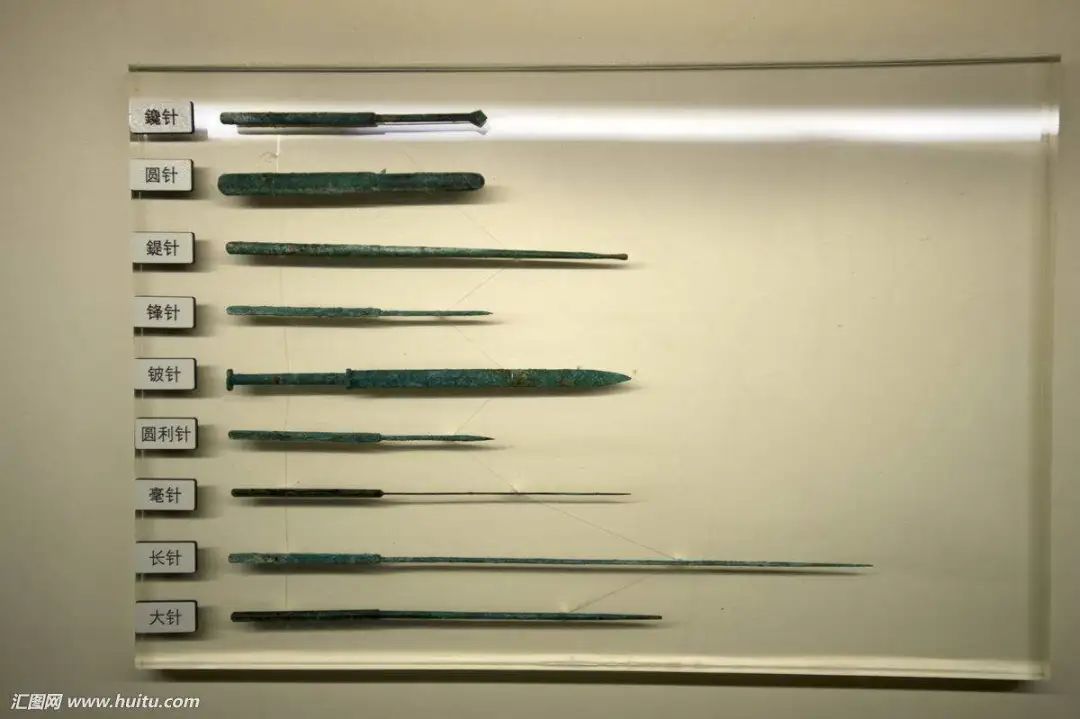

It is generally believed that TCM originated from the long-term labor practices of the ancient Chinese people, representing their perception and description of life phenomena, as well as the rich and precious material and spiritual wealth left behind in the struggle against nature and diseases. There are generally three theories regarding the origin of medicine: one claims it began with the Yellow Emperor, another with Shennong, and the third with Fuxi, who are regarded as the founders of TCM, pharmacology, and acupuncture, respectively. As early as the end of the primitive society, TCM had taken shape, but due to the lack of written records, only some myths and legends remain, such as “Shennong tasting a hundred herbs,” “Fuxi creating nine needles,” and “the art of Qi Huang.” The “Book of Han: Arts and Literature” points out that moxibustion, acupuncture, and herbal medicine are the three basic treatment methods of TCM, where moxibustion originated from the application of fire, acupuncture from the use of stone tools, and herbal medicine from the search for food. These accidental discoveries in the primitive stage gradually developed into a defined body of knowledge, forming the source of TCM development.

Figure 1: Ancient Nine Needles Diagram (Acupuncture Tools)

2. The Spring and Autumn of Medical History

During the Shang Dynasty, or even earlier, people’s understanding of nature was still in a primitive stage, with shamanism prevalent. At that time, the roles of shaman and physician were combined, referred to as shaman officials, and medical skills were merely a means controlled by these officials, lacking independent diagnostic and treatment authority. After the establishment of herbal decoction by Yi Yin, the prime minister of the Shang Dynasty, medicine and shamanism began to diverge.

1. TCM Theory from the Warring States to the Qin and Han Dynasties

The Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods were times of great change in Chinese history, with unprecedented activity in thought, culture, and scholarship. “Various schools of thought emerged, and a hundred schools contended,” leading to unprecedented development in the foundational theories and clinical medicine of TCM, accumulating a wealth of diagnostic and treatment experience. The widespread use of bronze tools also began to replace stone and bone needles in medicine, promoting the development of acupuncture and surgery. In terms of diagnosis, the “Rites of Zhou” recorded methods of judging life and death through sound and color observation. In treatment, acupuncture, herbal medicine, guiding exercises, and massage were comprehensively applied. At that time, physicians began to study medical theory based on practical experience, gradually introducing ancient philosophical concepts of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements as reasoning tools into medicine, laying the theoretical foundation of TCM.

During this period, a number of accomplished and influential medical figures emerged, such as the renowned physician Bian Que during the Warring States period; Hua Tuo, the “father of surgery,” who was the first to invent herbal anesthetics for surgical procedures during the Eastern Han Dynasty, and Zhang Zhongjing, the “sage of medicine,” who authored the immortal work “Treatise on Febrile Diseases” and established the principle of syndrome differentiation in TCM. The emergence of the four classic texts of TCM, namely “Huangdi Neijing” (The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon), “Nanjing” (The Classic of Difficult Issues), “Shennong Bencao Jing” (Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica), and “Shanghan Lun” (Treatise on Febrile Diseases), marked the formal establishment of the theoretical system of TCM, entering a stage of comprehensive development.

2. Development of Clinical Medicine in the Jin and Tang Dynasties

Since the Jin Dynasty, China gradually became unified, and society was relatively stable and prosperous, leading to rapid growth in TCM. The prevalence of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism also influenced the thoughts and practices of medical scholarship.

The prosperity of medicine during the Jin and Tang Dynasties was specifically manifested in the emergence of large comprehensive medical works, the most representative being “Emergency Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold” by Sun Simiao, known as the “King of Medicine.” This was the first major medical work in China, divided into 232 sections and containing over 5,300 prescriptions, integrating the medical achievements before the Tang Dynasty, and is regarded as the earliest clinical practical encyclopedia in China. Another manifestation was in acupuncture, with Huangfu Mi authoring the earliest existing specialized book on acupuncture, “The Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion,” which became a standard for future acupuncture studies. Ancient Japan and Korea also regarded this book as a textbook for learning acupuncture. Huangfu Mi is also the only historical figure in ancient China who is on par with Confucius in the history of world culture.

3. The Era of Medical Contention in the Song, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties

The Song Dynasty adopted a civil official governance system, emphasizing the cultivation of scholars, with some entering the field of medical research, improving the level of the medical workforce, leading to the emergence of “Confucian physicians” who were proficient in both medicine and Confucianism. The famous saying by the Song Dynasty politician Fan Zhongyan, “Worry before the world worries, and rejoice after the world rejoices,” reflects this spirit, along with another influential saying, “If not for a good minister, I would wish to be a good physician.” Thus, during the Song Dynasty, it became a trend for literati to understand medicine, with everyone from monarchs and ministers to commoners taking pride in their medical knowledge. Notable figures included politician Sima Guang, poet Lu You, writer Su Shi, and scientist Shen Kuo, all of whom were well-versed in classics and history, as well as skilled in medicine. Additionally, in the field of acupuncture, the work “Illustrated Classic of Acupuncture” compiled by Wang Weiyi and his invention of the acupuncture bronze man marked a milestone event, signifying a significant transformation in acupuncture teaching methods.

Figure 2: Acupuncture Bronze Man

By the Jin and Yuan periods, various schools of TCM emerged, with the most famous being the Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan: Liu Wansu, Zhang Congzheng, Li Gao, and Zhu Zhenheng, who established the four major schools of “Cold and Cool School,” “Evil Attacking School,” “Earth Supplementing School,” and “Yin Nourishing School,” opening an era of diverse TCM academic schools, greatly enriching the connotation of TCM.

Figure 3: The Four Great Masters of the Jin and Yuan

4. Development of Pharmacology in the Ming Dynasty

The achievements of Chinese medicine during the Ming Dynasty are mainly reflected in the monumental work “Compendium of Materia Medica,” authored by the renowned naturalist Li Shizhen. After more than 30 years of effort, he completed this monumental work in pharmacology. After its publication, it became widely popular across the country and was later translated into various languages, including German, English, Latin, and Russian, spreading worldwide. The “Compendium of Materia Medica” not only provides detailed records of pharmacology but also integrates a wealth of scientific data, making it rich in content. This book was praised by Darwin as “an ancient Chinese encyclopedia.”

5. The Warm Disease School of the Qing Dynasty

The so-called warm diseases refer to epidemic infectious diseases that often occur in the culturally rich and temperate regions of Jiangsu and Zhejiang. The Warm Disease School originated in the late Ming Dynasty, founded by Wu Youke, and flourished during the Qing Dynasty. The “Four Great Masters of Warm Disease” at that time, Ye Gui, Xue Xue, Wu Tang, and Wang Tuxiong, proposed the mechanisms of warm epidemic diseases and the theories of warm diseases, achieving significant accomplishments. Among them, Ye Tianshi’s “Theory of Warm Heat” is revered as a classic by the Warm Heat School.

3. Medical Anecdotes

1. The Origin of the Title “Doctor”

The term “doctor” first appeared in the “Tang Liudian”: “Forty doctors, two scholars,” referring to those who study medicine. During the Tang Dynasty, schools were established for medical training, and anyone studying medicine was called a doctor, which does not completely equate to today’s doctors. Before the Tang Dynasty, those practicing medicine had various titles, such as minor disease ministers, disease physicians, and chief physicians. During the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties, due to the emphasis placed on medicine by successive emperors, the management of medical affairs became increasingly refined, establishing specialized medical officer systems, such as the Hanlin Medical Officer Bureau and the Tai Hospital. However, the titles for practitioners remained inconsistent until modern times, when “doctor” became the common term for those treating patients.

2. The Difference Between “Daifu” and “Langzhong”

“Daifu” is an ancient official title in China, representing a high social status. Below the monarch, there were three ranks: minister, daifu, and scholar. In the Spring and Autumn period, daifu was divided into upper, middle, and lower ranks according to position. However, these were not medical officials. It was not until the reign of Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty that the ranks were redefined, establishing positions such as daifu and langzhong among medical officials, making daifu the highest rank among them. Thus, the chief physician was specifically referred to as daifu. After the late Tang and Five Dynasties, physicians began to be called “daifu.” To distinguish from the official title, physicians were referred to as “dai (大) fu.”

“Langzhong” is an ancient official title in China, originating from the Warring States period and continuing until the Qing Dynasty, referring to senior officials below the Minister and Deputy Minister. It was abolished in the late Qing Dynasty. Since there was a position of langzhong among medical officials during the Song Dynasty, society began to refer to physicians by this title.

3. What is “Bencao”

The term “bencao” originates from the “Shennong Bencao Jing” and has been used for hundreds of years, becoming a general term for all Chinese medicinal materials. Why are all herbal medicines collectively referred to as “bencao”? According to Han Baosheng from the Five Dynasties, “Among medicines, there are jade and stone, grass and wood, insects and beasts, and the term bencao is used because the grass category is the most abundant among all medicines.” This is the most widely accepted explanation for the collective term “bencao” for Chinese medicinal materials over time. The “Shuo Wen Jie Zi” states: “Medicine is the grass that treats diseases, derived from grass.” This reflects the initial situation where only plant medicines were used. Although later, animal and mineral medicines were discovered, this concept was retained, so later generations referred to all medicines collectively as “bencao.”

4. The Origin of the Term “Tang”

It is said that the famous physician Zhang Zhongjing, after being appointed as the governor of Changsha, regularly treated the sick in the main hall of the government office. When practicing medicine, he would sit in the main hall to diagnose and treat the public. Later, people began to refer to doctors who treated patients in pharmacies as “sitting hall doctors.” These doctors also named their pharmacies as “XX Tang,” and now TCM clinics or pharmacies are also referred to as “Tang,” originating from this practice.

4. Conclusion

The culture of TCM is vast and profound, embodying simplicity and beauty. Approaching TCM allows one to appreciate a different aspect of Chinese culture.