Once you pay attention, you will benefit for a lifetime, free secret recipes!

Today we will learn the methods of pulse diagnosis. Pulse diagnosis, also known as pulse taking (qie mai), is a method where the physician uses their fingers to press on the patient’s pulse, perceiving the pulse’s characteristics to understand the condition and diagnose the disease. Pulse diagnosis is an important part of the four diagnostic methods in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which include observation, listening, inquiry, and palpation. Many people find pulse diagnosis quite magical; in the past, without many diagnostic instruments, traditional Chinese medicine explored the functions of the five organs and six bowels through pulse diagnosis, sensing the state of the body, which is indeed fascinating!

However, from a learning perspective, pulse diagnosis is relatively difficult to master. Some describe pulse diagnosis as: “like peering into an abyss and meeting floating clouds.” What does this mean? It means that pulse diagnosis is like an abyss that seems bottomless, and like the floating clouds in the sky, it changes without a fixed shape.

Pulse diagnosis has a long history. As early as in the Huangdi Neijing, methods such as the “Three Parts and Nine Pulses” and “Renying Qi Kou” were recorded. The Nanjing first advocated the method of “taking the pulse at the cun (寸) position,” which has been followed by later generations. Zhang Zhongjing established the principle of “Ping Mai Bian Zheng” (differentiating patterns through pulse) and created the three-part diagnostic methods of cun, renying, and fuyang (taixi).

Wang Shuhe’s Pulse Classic inherited the three parts and nine pulses, and established twenty-four pulse types, making it the earliest existing monograph on pulse studies in China. Li Shizhen’s Binhu Pulse Studies recorded twenty-seven pulse types and compiled “seven-character verses” for easier memorization. Li Shicai’s Diagnosis with Correct Vision added disease pulses, totaling twenty-eight pulse types.

Why can pulse diagnosis reflect our bodily conditions? This requires understanding the principles of pulse formation. The pulse image is the manifestation of the pulse’s movement. The formation of the pulse image is directly related to the heart’s beating, the patency of the pulse vessels, and the balance of qi and blood. The blood vessels of the human body connect throughout, linking the internal organs and reaching the surface, circulating qi and blood continuously. Thus, the pulse image can reflect the overall function of the internal organs, the balance of yin and yang, and the state of qi and blood.

(1) The heart is the main organ forming the pulse image.

The heart governs the blood vessels, and the heart’s beating drives the blood to flow normally within the vessels, thus forming the pulse. Therefore, the heart is the main organ forming the pulse image, and the heart’s beating is the driving force behind the pulse image. The pulse’s frequency, regularity, strength, and weakness correspond to the heart’s beating frequency, rhythm, and strength. The heart’s beating and the blood’s flow in the vessels are governed by the heart qi and propelled by the zong qi. Thus, Ling Shu states: “Zong qi accumulates in the feet… in the throat, to connect the heart pulse and facilitate breathing.” Suwen: On the Essentials of Pulse states: “The pulse is the residence of blood.” The pulse is where qi and blood converge, and the structure and function of the vessels can affect the pulse image.

(2) The movement of qi and blood is the foundation for forming the pulse image.

Qi and blood are the fundamental substances that constitute and maintain human life activities, and they are also the material basis for the formation of the pulse image. Qi is the commander of blood; it can generate, move, and retain blood. The blood’s movement in the vessels relies on the propulsion and retention of qi; the strength and rhythm of the heart’s beating also depend on the regulation of qi. Blood is the carrier of qi, and the vessels rely on blood to be filled and nourished; the balance of blood directly relates to the size of the pulse image. Therefore, qi and blood are crucial for the formation of the pulse image. For example, when qi and blood are sufficient, the pulse image is harmonious and strong; when qi and blood are insufficient, the pulse image is thin and weak; when qi stagnates and blood clots, the pulse image is stagnant and obstructed.

(3) The coordination of the five organs ensures a normal pulse image.

The formation of the pulse image is not only related to the heart and blood but also requires the coordination and cooperation of the other four organs. The lungs govern qi and control respiration, connecting to all pulses and participating in the generation of zong qi, thus regulating the movement of qi and blood throughout the body, assisting the heart in circulating blood. The spleen and stomach are the foundation of postnatal life, the source of qi and blood generation, determining the amount of “stomach qi” reflected in the pulse image; the spleen governs blood, ensuring that blood circulates within the vessels without overflowing, relying on the spleen’s qi to regulate it.

The liver stores blood, regulating blood volume; the liver governs the smooth flow of qi and blood. The kidneys store essence, being the root of both yuan yin and yuan yang, and are also the “root” of the pulse image; kidney essence can transform into blood and is one of the important material bases for blood. Thus, the formation of a normal pulse image relies on the coordinated functions of the five organs.

Why is it said that learning pulse diagnosis is difficult? Wang Shuhe stated in the Pulse Classic: Preface: “The principles of pulse are subtle and intricate, difficult to discern; the tight and floating pulses, turning and resembling each other, are easy to understand in the heart, but difficult to clarify under the fingers.”

The principles of pulse studies are very precise and profound. Those who study pulse often find it easy to understand the theory of what pulse types correspond to which diseases, yet in practice, they often struggle to grasp the specific pulse images under their fingers. Many pulse images are very similar, and without careful differentiation, it is difficult to distinguish them. For example, the string pulse and tight pulse, floating pulse and hollow pulse, etc. The pathological mechanisms reflected by these similar pulses can be vastly different. Mistaking one for the other can lead to misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

Some say that pulse diagnosis must be taught hand-in-hand by a teacher; otherwise, it is difficult to learn and master.

In fact, this statement is somewhat biased. Just like the transmission of TCM, some people learn through following a teacher or family tradition, while others may have a high level of self-study and can become proficient independently. First, pulse diagnosis, like other diagnostic methods and therapies in TCM, requires repeated training and learning. It is unrealistic to expect that after reading a pulse book today, one can master pulse diagnosis proficiently tomorrow; it requires careful comprehension and repeated contemplation, and only then can one gradually master the techniques of this diagnostic method.

Wang Shuhe said: “If you mistake a sinking pulse for a hidden one, the treatment will be forever misguided; if you mistake a slow pulse for a delayed one, danger will immediately ensue.” Therefore, accurately grasping the pulse image is an important part of diagnosing diseases. To accurately grasp the pulse image, one must not only master the basic theories of pulse studies but also pay special attention to practice and verification. As the saying goes, “Reading Wang Shuhe thoroughly is not as good as practicing in clinical settings more often.” Through continuous experience and repeated comparisons, one can gradually accumulate rich experience in pulse diagnosis.

Pulse diagnosis itself relies on the physician’s sensitive touch to carefully experience and identify. Therefore, learning pulse diagnosis must involve mastering the basic theories and skills of pulse studies, repeated practice, and careful understanding to achieve the goal of recognizing various pulse images and guiding clinical differentiation.

“Timing”

The best time for pulse diagnosis is early morning (ping dan), before getting out of bed and before eating.

In Suwen: On the Essentials of Pulse, it states: “Diagnosis is often done at ping dan, when yin qi has not yet moved, yang qi has not yet dispersed, food and drink have not yet been consumed, the meridians are not yet full, the collaterals are balanced, and qi and blood are not yet chaotic, thus it is possible to diagnose the pulse accurately.”

What is ping dan? It is when the sun has just risen above the horizon, in the early morning before eating or engaging in activities, when yin and yang have not yet moved, qi and blood are not yet chaotic, and the meridians are balanced. At this time, the internal and external environment of the body is relatively stable, and the pulse image can accurately reflect the body’s basic physiological state, making it easier to detect pathological pulse images. Therefore, this time is the best for pulse diagnosis.

However, this does not mean that pulse diagnosis cannot be performed at other times. The Pulse Classic states: “When diagnosing disease pulses, it is not limited to day or night.” Due to current diagnostic conditions, pulse diagnosis can be performed at any time, but there is one requirement: the patient must maintain a calm mood, and the qi and blood must be stable. The examination room should also be kept quiet to minimize external disturbances, which is conducive to the physician’s focused experience of the pulse image, leading to accurate diagnosis.

The operation time for pulse taking should be no less than 1 minute for each hand, and about 3 minutes for both hands.

“Position”

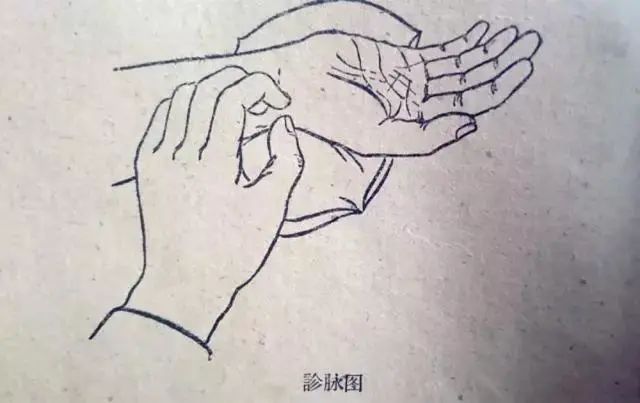

During pulse diagnosis, the patient’s position, whether sitting or lying down, should have the arms extended to the sides and laid flat. This allows for smoother blood flow and does not affect the pulse image.

The patient’s arms should be extended and not compressed. The arms should be level, and there is a concept called “ping xin,” meaning that the position of the hands should be at the same level as the heart. They should be approximately at the same height as the heart. If the hands are raised to take the pulse, the pulse will definitely be inaccurate. Therefore, strict operation requires the arms to be level and the heart to be level.

“Finger Technique”

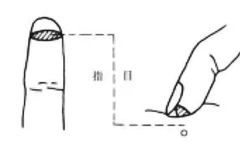

Which fingers should be used for pulse diagnosis? The index finger, middle finger, and ring finger are the three fingers used. When taking the pulse, the three fingers should be at the same level, slightly bent at about 45 degrees. Where should the fingers touch the pulse? At the “finger tip,” which is between the fingertip and the finger belly, this is what TCM refers to as “finger tip touching the pulse.”

The requirement for “finger tip touching the pulse” is taught in current TCM diagnostic textbooks. The term “finger tip” occasionally appears in literature but is generally not a medical term. This area does not have a clear anatomical location. The term “finger tip” comes from the Pulse Classic, written by Ye Lin in the Qing Dynasty, which states, “If the tip of the finger is raised like a line, it is called the finger tip, used to press the pulse ridge.” This single sentence is unclear on how it became the gold standard for pulse diagnosis in textbooks.

In clinical practice, it is actually sufficient to use the finger belly to feel the pulse. The width, thickness, and pulsation of a pulse involve the surrounding muscles and skin, and it is difficult to fully assess using just the finger tip.

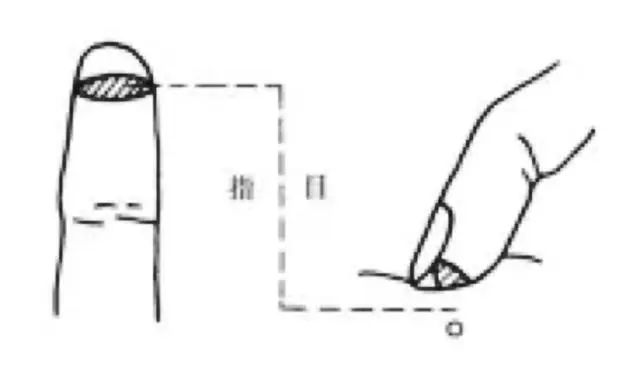

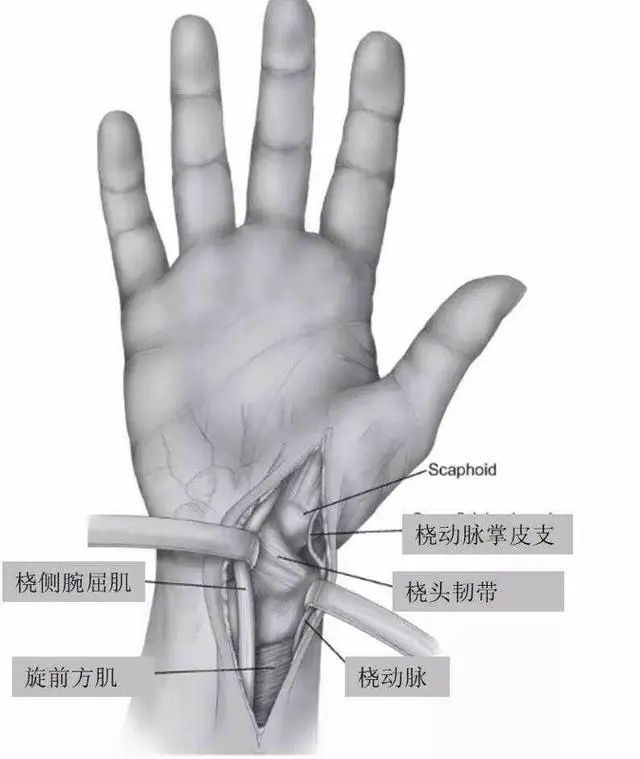

The second issue is the placement of the fingers. According to TCM pulse diagnosis theory, the left and right hands’ cun, guan, and chi correspond to different organs: left cun corresponds to the heart, right cun corresponds to the lungs, left guan corresponds to the liver, right guan corresponds to the spleen, left chi corresponds to the kidneys, and right chi corresponds to the mingmen (gate of life). Everyone can extend their hands, palm side up, to see the so-called prominent bone at the back of the hand. This protruding bone is located at the radial side of the wrist, behind the thumb, and is called the guan position.

The guan position is the front part—”front” refers to the direction closer to the hand. The front of the guan is yang, and the back of the guan is yin. This yang position, the front of the guan, is called cun, and the back of the guan, the yin position, is called chi, thus referred to as “yang cun, yin chi.” Why is it called cun? Because the distance from the prominent bone at the back of the hand to the wrist crease is exactly one cun according to TCM’s own measurement. And why is it called chi? Because the distance from the guan position to the elbow crease is exactly one chi.

The first step in placing the fingers for pulse taking is to cross the hands, meaning the physician’s left hand presses on the patient’s right hand, and the physician’s right hand presses on the patient’s left hand. Only this way can the index finger be placed on the cun pulse, the middle finger on the guan pulse, and the ring finger on the chi pulse. Many physicians do not do this; one hand holds a pen while the other presses on the left hand and then the right hand. No matter how they press, both hands cannot be on the cun pulse, so this method is incorrect.

If one is indeed accustomed to using only one hand to take the pulse, they should ensure to use the same hand consistently: the sensory perception of the two hands is different, so using the same hand for pulse diagnosis ensures accurate and effective processing of information by the brain. It is crucial to avoid using the left hand one day and the right hand the next.

The second step is to determine the guan position with the middle finger. The three fingers should first use the middle finger to locate the guan pulse, which is the most prominent area. Sliding along this high point will determine the guan pulse. Additionally, depending on the individual’s size and length, the three fingers should be appropriately spaced.

“Finger Movement”

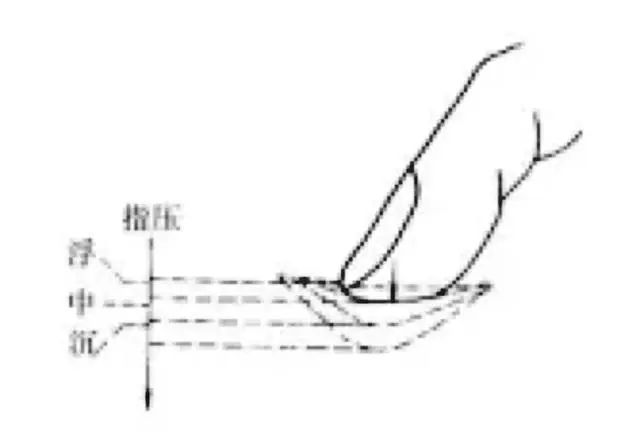

Finger movement refers to the physician’s use of finger strength, movement, and changes in finger placement to perceive the pulse image. Common finger techniques include lifting, pressing, seeking, total pressing, and single diagnosis.

1. Lifting, Pressing, Seeking

Lifting, pressing, and seeking are the basic finger techniques in pulse diagnosis. They involve varying the pressure of the three fingers to examine the pulse’s floating, sinking, and strength. As Shou said: “The essentials of holding the pulse are three: lifting, pressing, and seeking. Lightly touching it is called lifting; pressing down hard is called pressing; and applying moderate pressure to seek is called seeking.”

Lifting refers to the physician’s fingers lightly pressing on the cun pulse area to perceive the pulse image. The lifting technique is also known as “floating taking.”

Pressing refers to the physician’s fingers applying heavier pressure, even pressing down to the muscles and bones to perceive the pulse image. The pressing technique is also known as “sinking taking.”

Seeking means to search; the physician often uses their fingers from light to heavy, and from heavy to light, pushing and seeking left and right; or carefully searching for the most prominent pulse movement in the cun, guan, and chi positions, or adjusting the most appropriate finger strength to find the most distinct characteristics of the pulse movement. Applying neither light nor heavy pressure, pressing to the muscles to take the pulse is called “medium taking.”

During pulse diagnosis, one should carefully observe the changes in the pulse image between lifting, pressing, and seeking.

2. Total Pressing and Single Diagnosis

Total pressing is a method where all three fingers apply equal pressure to diagnose the pulse, allowing for an overall differentiation of the shapes, positions, and strengths of the pulses in the cun, guan, and chi positions, as well as between the left and right hands.

Single diagnosis is a method where one finger examines a specific pulse image. It is mainly used to understand the position, sequence, shape, and characteristics of the pulses in the cun, guan, and chi positions.

When clinically starting pulse diagnosis, what are the basic steps? Here I will introduce my pulse diagnosis practice methods for beginners as a reference.

First, apply even pressure with the three fingers, floating over the cun, guan, and chi; continue with equal pressure for medium taking. Some pulse images can be discovered through this initial examination. For example, when experiencing wind-cold externally, the pulse image will generally show a floating layer with a tight string-like appearance.

Next, focus on the tip of the index finger, on the cun pulse, exploring from shallow to deep, layer by layer. Then focus on the tip of the middle finger, on the guan pulse, gradually delving deeper, followed by the chi position. This way, layer by layer, the examination should last no less than one minute on each side to clarify the pulse image.

After completing the examination, perform the same process on the other hand.

“Calmness”

Calmness refers to the physician’s breathing being steady and even. Why is it important to be calm? In ancient times, there were no clocks, and to observe the sun’s movement, if it moved too slowly, a few minutes might pass without any noticeable change. Thus, one had to rely on breathing to count the patient’s pulse. The purpose of calmness is twofold: on one hand, it allows the physician to maintain steady breathing, clear the mind, and count the patient’s pulse accurately; on the other hand, calmness helps the physician concentrate, enabling careful differentiation of the pulse image.

“Fifty Pulses”

Fifty pulses emphasize the pulse’s beating. What does fifty pulses mean? It means that during pulse diagnosis, one should generally count at least 50 beats. Of course, the focus is not solely on the number; if one is solely focused on counting, 1, 2, 3, 4, and counts to 50, they may not truly experience the pulse’s floating, sinking, strength, and weakness! The purpose is to emphasize that pulse taking should not be rushed.

One should take a certain amount of time to experience the pulse. Generally, for fifty beats or a hundred beats, it may take about 2 to 3 minutes. The ancients emphasized fifty beats because it was believed that the wei qi (defensive qi) circulates in the body in fifty beats, reflecting any issues with the five organs and six bowels.

“Elements of Pulse Image”

What exactly should be diagnosed during pulse diagnosis? The identification of pulse images mainly relies on the physician’s finger sensations. There are many types of pulse images, and TCM literature often analyzes and summarizes them from four aspects: position, frequency, shape, and quality, which relate to the pulse’s frequency, rhythm, the area of manifestation, length, width, the fullness and tension of the pulse vessels, the smoothness of blood flow, and the strength of the heart’s beating.

In modern times, through in-depth understanding of pulse literature and summarizing clinical research data, the main factors constituting various pulse images can be roughly categorized into eight aspects: pulse position, frequency, length, width, strength, rhythm, smoothness, and tension. Mastering these basic elements is crucial for understanding the characteristics and formation mechanisms of various pulse images, serving to simplify complex concepts.

1. Pulse Position

Refers to the depth of the pulse’s manifestation. A superficial pulse is called a floating pulse; a deep pulse is called a sinking pulse. The depth of the pulse is mainly perceived through the pressure applied by the fingers.

2. Frequency

Refers to the pulse’s rate. In normal adults, a pulse of four to five beats per breath is considered a normal pulse; a pulse of more than five beats per breath is called a rapid pulse; a pulse of less than four beats per breath is called a slow pulse.

3. Length

Refers to the axial range of the pulse’s movement, i.e., a pulse that extends beyond the cun, guan, and chi positions is called a long pulse; a pulse that does not reach the three positions but is felt at the guan or cun and guan positions is called a short pulse.

4. Width

Refers to the radial range of the pulse’s movement, i.e., the thickness perceived under the fingers. A wide pulse is called a large pulse, and a narrow pulse is called a thin pulse.

5. Strength

Refers to the strength of the pulse. A strong pulse is felt as vigorous under the fingers, while a weak pulse is felt as feeble.

6. Rhythm

Refers to the uniformity of the pulse’s rhythm. This includes two aspects: whether the pulse rhythm is uniform and whether there are any pauses; and whether the number and duration of pauses are regular.

7. Smoothness

Refers to the smoothness of the pulse’s onset. A pulse that comes smoothly and roundly is called a slippery pulse; a pulse that is difficult to feel and not smooth is called a rough pulse.

8. Tension

Refers to the urgency or relaxation of the pulse vessels. The tension of the pulse is mainly reflected in the pulse’s length, tension, and changes in the pulsation felt under the fingers. A high tension pulse is like a string pulse or tight pulse; a relaxed pulse can be seen in a slow pulse.

The above are the basic elements that constitute the pulse image and the basic points for perceiving the pulse image. The identification of pulse images mainly relies on the physician’s finger sensations. Therefore, when examining the pulse, the physician must carefully perceive and analyze the various pulse image elements comprehensively to gradually master the characteristics of various pulse images and correctly identify and judge various pathological pulses.

Disclaimer: This is a reprinted article; for copyright issues, please delete it; treatment should be conducted under the guidance of a physician.

For bone diseases, use Heibaitong.

If you have difficulties, contact Xiang Ge.