The concepts of reality (实, shí) and illusion (虚, xū) are important categories in Chinese aesthetics, complementing and enhancing each other. “Reality” refers to tangible entities, while “illusion” pertains to the abstract, ethereal, and imaginary. Properly handling the relationship between reality and illusion is a crucial expressive technique in creating the artistic conception of Chinese painting. Below, we will briefly discuss the relationship between reality and illusion in painting and its impact on Chinese art.

Interplay of Reality and Illusion

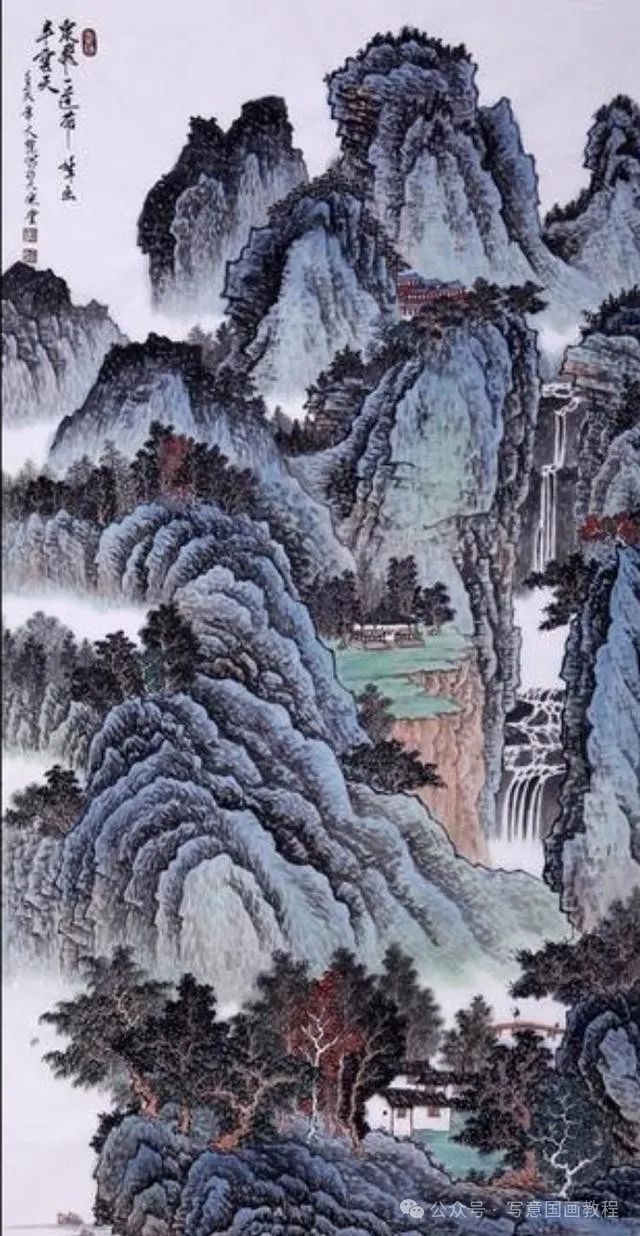

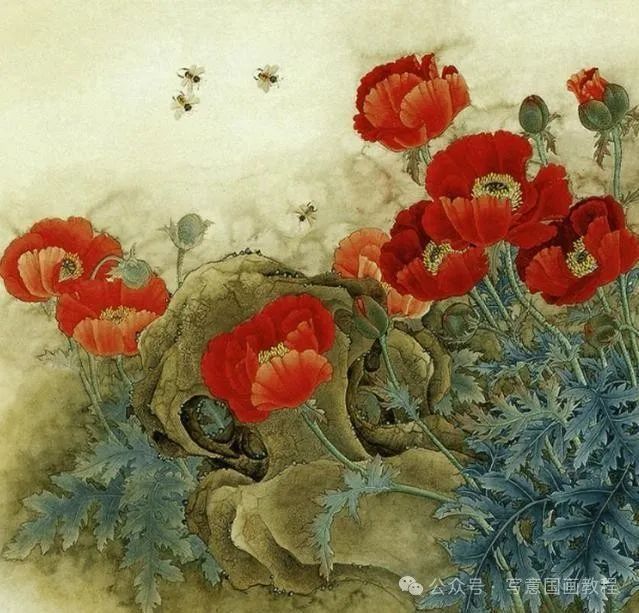

The layout of the composition aims to achieve a “diverse unity” in the imagery, with a focus on the concept of “opening and closing”. The term “opening and closing” manifests in two main aspects: one is the previously mentioned “guest and host correspondence”, and the other is the “interplay of reality and illusion”. “Reality” generally refers to prominent images in the painting, with clear outlines, rich and vibrant colors, and large, close objects. In contrast, “illusion” refers to vague images, light and distant colors, small objects, and blank spaces. However, these concepts of reality and illusion are relative; without “illusion”, there can be no “reality”, and vice versa.

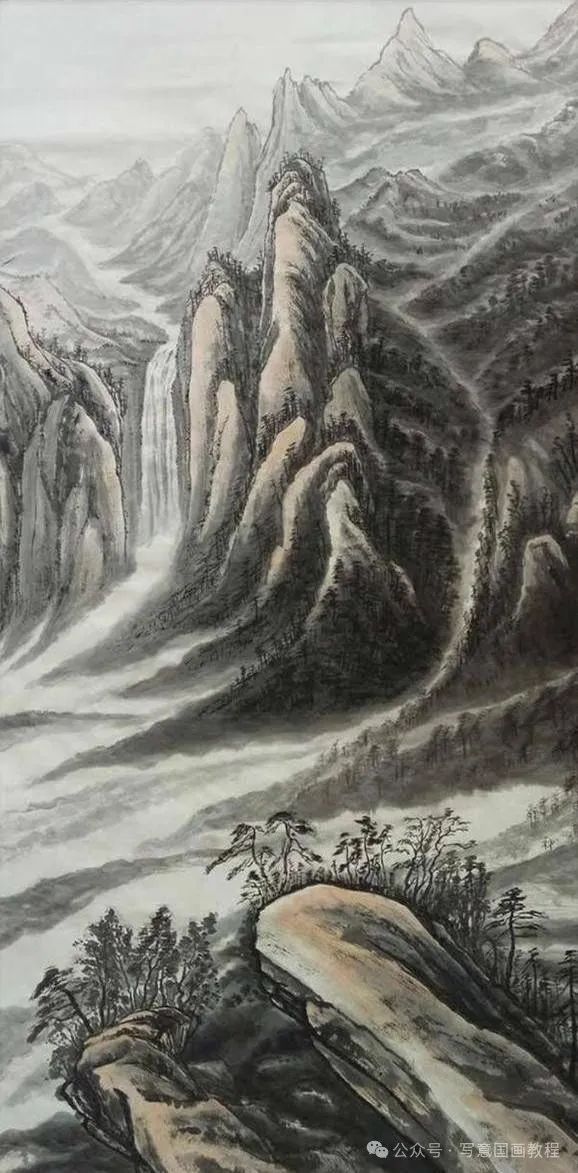

Mountains Represent Reality, Water Represents Illusion

In composition, not only the overall layout must distinguish between reality and illusion, but each part also has its own variations of reality and illusion, which is often referred to as “reality within illusion, and illusion within reality”. The main subject, often located prominently in the foreground, is depicted with clarity and detail, using bold brushwork and vibrant colors, thus forming the “real” part of the painting.

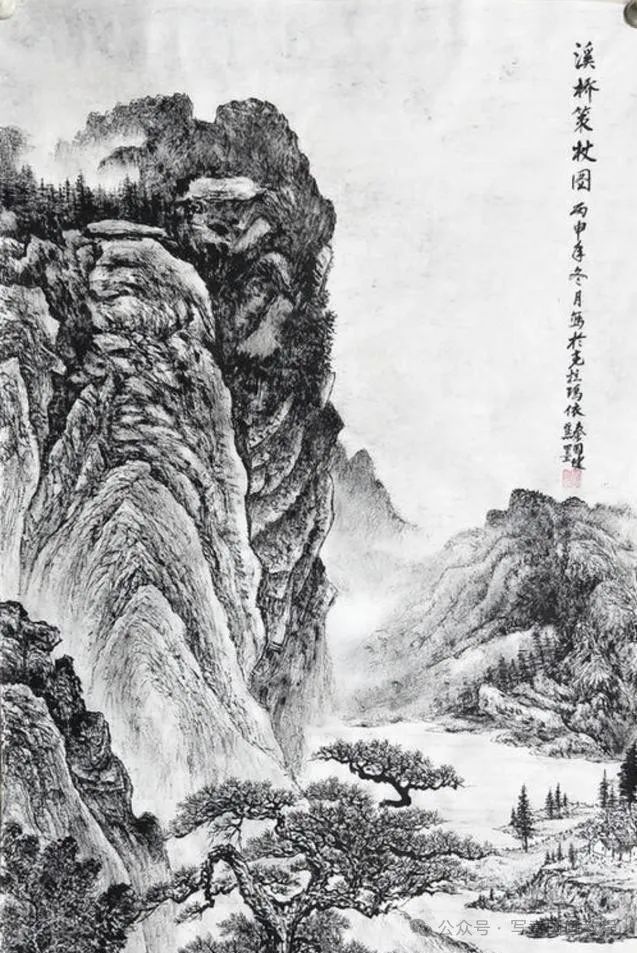

Reality Within Illusion, Illusion Within Reality

The accompanying elements, often in a subordinate position, are depicted more loosely and simply, with lighter and more subtle brushwork and colors, or even without any brushwork, relying solely on “broken lines to convey meaning”, thus forming the “illusory” part of the painting. If the main subject is too real, it can be softened by illusion; if the subordinate elements are too illusory, they can be filled with reality, mutually compensating and cooperating to achieve a diverse unity in composition.

In traditional Chinese landscape painting theory, there are many examples discussing the relationship between reality and illusion, which can also be applied to flower-and-bird painting. For instance, in the “Shicun Painting Treatise” by Kong Yanshi from the Qing Dynasty, it is stated: “Where there is ink, it is reality; where there is no ink, it is the clouds and mist that provide the illusion of reality. Trees, rocks, and buildings all have blank spaces, which are the illusion within reality. Reality is the illusion, and the illusion is reality.”

Interplay of Reality and Illusion

In the “Painting Treatise” by Da Zhongguang from the Qing Dynasty, it is said: “Mountains are made real by mist, and mountains are made illusory by pavilions.” Additionally, Dai Yiheng in his “Drunken Suzhai Painting Treatise” provides more practical examples, stating that beginners often find reality too stark; if it is real yet can be empty, it can be salvaged. What are the methods for achieving emptiness? I will detail the key points: “If the scene seems too real with bare trees, having water behind the trees can create emptiness. If the scene seems too real with double outlines of leaves, having empty spaces between the outlines can create emptiness. If the scene seems too real and seeks change, ancient leaves and sails can emerge from the treetops. If the scene seems too real and seeks exquisite techniques, the winding paths of stones can be depicted, or waterfalls can be layered. If the scene seems too real in the mountains, a flat slope can be used to create layers, all of which are essential methods for achieving reality in the scene.”

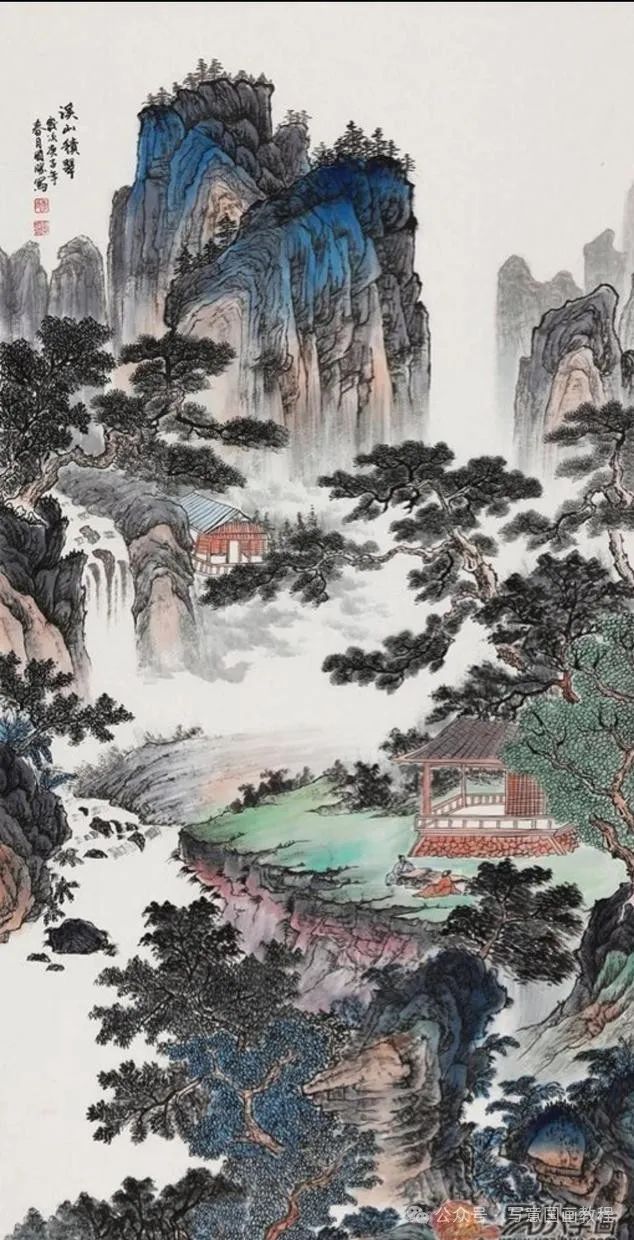

Crane Represents Reality, Leaves Represent Illusion

In the “Miscellaneous Discussions on Learning to Paint” by Jiang He from the Qing Dynasty, it is also mentioned: “Thirty percent of the success lies in the proper arrangement of heaven and earth, while seventy percent lies in the clouds and mist.” Although these examples discuss landscapes, one can find some rules of “interplay of reality and illusion” that can be applied to flower-and-bird painting. It is evident that “reality and illusion” align with the previously discussed concepts of “light and heavy” in imagery.

The rules of reality and illusion are: areas with brushwork are heavier than the sky, blank spaces are heavier than mountains and rocks, trees and woods are heavier than springs and clouds, animals like birds are heavier than plants like trees, and buildings like pavilions are heavier than natural elements like mountains and forests… using light to break heavy, and heavy to supplement light, is the method of “interplay of reality and illusion”. This principle also applies to flower-and-bird compositions.

Interplay of Reality and Illusion, Balanced Appropriately

For example, if one side of the painting features a cluster of bright flowers while the other side is blank, if it feels too empty, adding a couple of bees or butterflies, although small in area, can create a sense of balance and vitality, which is “reality within illusion”. Conversely, if the painting has a dense mass of dark leaves that feels too heavy, simply adding a few white flowers among the leaves or leaving some gaps to include parts of branches can break the heaviness, allowing colors to breathe and enhancing the sense of ease, which is “illusion within reality”.

Furthermore, in the composition of flowers, the arrangement of overlapping and interspersing, where leaves are behind flowers and flowers are behind leaves, layer upon layer supports the sense of space, also embodies the principle of “reality within illusion and illusion within reality”.

Interplay of Reality and Illusion, Vitality and Spirit

Additionally, a white crane, set against the backdrop of lush green pines, creates a striking contrast and a prominent image. In this case, from a physical perspective, the crane is the real part, while the pine is the illusory part; however, from a color perspective, the pine becomes the real part, and the crane becomes the illusory part. This again illustrates the “illusion within reality and reality within illusion” from another angle. In summary, understanding the composition in terms of this dialectical principle of “the illusory is actually real, and the real is actually illusory” allows for flexible application across various contexts.