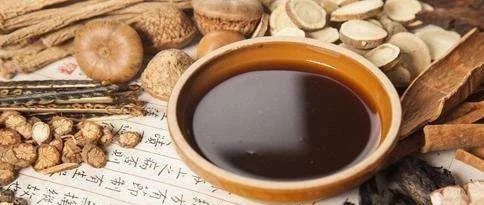

Mr. Zhao Bingnan is a renowned expert in TCM dermatology, with over 60 years of clinical experience. He has developed a unique style of treatment in dermatology through long-term clinical practice. Mr. Zhao began his apprenticeship at the age of 13 under the famous physician Ding De’en, studying TCM dermatology and systematically researching classical TCM surgical texts and the preparation of surgical medicines. He also self-studied TCM classics such as the Huangdi Neijing and Shanghan Lun, achieving profound knowledge in both TCM surgery and internal medicine.

Over his 60 years of practice, Mr. Zhao has formulated 108 external and internal formulas, which he generously donated to the Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine where he worked. These internal and external formulas are still widely used in clinical practice today.

Among the internal formulas developed by Mr. Zhao, three stand out for their distinctive features and remarkable efficacy: the Jing Fang (Schizonepeta and Saposhnikovia Decoction), Ma Huang Fang (Ephedra Decoction), and Quan Chong Fang (Scorpion Decoction), collectively referred to as the “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment.” These formulas are included in the section on experience formulas in the book Clinical Experience Collection of Zhao Bingnan. The original text describes the indications of these three formulas, which share similarities yet have distinct differences. The Jing Fang has the effects of dispelling wind and relieving the exterior, as well as clearing heat and stopping itching, primarily treating acute urticaria and angioedema; the Ma Huang Fang opens the pores and harmonizes the blood to stop itching, mainly treating chronic urticaria; the Quan Chong Fang extinguishes wind and stops itching, detoxifying and dispelling dampness, primarily treating chronic eczema, chronic scrotal eczema, neurodermatitis, and nodular prurigo, among other chronic stubborn pruritic skin diseases. The guidelines state: “If the disease course is short, with bright red rashes and the disease is superficial, first use Jing Fang; if the disease course is long and has begun to enter the interior, then use Ma Huang Fang; for long-standing cases that do not heal, one may use Qin Jiao Wan or Quan Chong Fang.

In our clinical practice, we have applied Mr. Zhao’s “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment” to patients with lung-related diseases accompanied by skin symptoms, and after treatment, both the lung symptoms and skin symptoms showed significant improvement. According to TCM theory, the lungs are associated with the skin and hair, suggesting that formulas for treating skin diseases should have commonalities with those for treating lung diseases. The most common lung-related diseases are exogenous diseases caused by external pathogens, thus we attempt to re-examine Mr. Zhao’s “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment” from the perspective of TCM theory on exogenous diseases to deepen our understanding of these formulas and promote their flexible application in clinical practice.

1.Analysis of Jing Fang from the Perspective of Wind-Heat

The Jing Fang consists of 12 herbs: Jing Jie (Schizonepeta), Fang Feng (Saposhnikovia), Jiang Can (Silkworm), Jin Yin Hua (Honeysuckle), Niubang Zi (Burdock Seed), Dan Pi (Moutan Root), Zi Bei Fu Ping (Lemna), Gan Cao (Licorice), Bo He (Mint), Huang Qin (Scutellaria), Chan Yi (Cicada Slough), and Sheng Gan Cao (Raw Licorice). This formula is specifically designed for acute urticaria leaning towards wind-heat, with a disease course of less than 1 month. Mr. Zhao emphasized dispelling the wind-heat pathogen when formulating this recipe. The pathogenic mechanism involves “wind in the defensive layer… heat excessive in the nourishing layer… wind injures the skin and heat injures the blood vessels.” The Su Wen: Zhi Zhen Yao Da Lun states: “Wind invades internally, treated with pungent-cool, assisted with bitter-sweet… heat invades internally, treated with salty-cold, assisted with sweet-bitter,” establishing the basic principles of treatment for wind-heat pathogens using pungent-cool, salty-cold, and bitter-sweet substances.

Both Jing Jie and Fang Feng focus on dispersing wind pathogens, while Bo He, Jin Yin Hua, and Niubang Zi are pungent and cold, assisting in dispersing wind and clearing heat; Chan Yi and Jiang Can are key herbs for treating warm-heat epidemic pathogens, both having a cooling and salty nature, which can penetrate the qi level to expel pathogens and enter the blood level to clear heat; Dan Pi, Huang Qin, and Sheng Gan Cao are bitter, cold, sweet, and salty, clearing heat to stabilize the blood level. Zi Bei Fu Ping promotes sweating and diuresis, targeting the pathological mechanism of urticaria—acute edema of the skin and mucous membranes, making it a specific remedy.

The formulation approach of Mr. Zhao’s Jing Fang is similar to that of Yin Qiao San from Wen Bing Tiao Bian, both using Jin Yin Hua, Jing Jie, Niubang Zi, and Bo He to disperse wind-heat pathogens. However, Yin Qiao San includes Lian Qiao (Forsythia), Jie Geng (Platycodon), and Lu Gen (Reed Rhizome), which specifically target sore throat symptoms at the onset of warm diseases, while Mr. Zhao’s formula does not include these herbs as there are no throat pain symptoms, instead adding Jiang Can, Chan Yi, and Zi Bei Fu Ping to enhance the power of dispelling wind, stopping itching, and resolving rashes, and adding Dan Pi, Huang Qin, and Sheng Di Huang (Rehmannia) to cool the blood and stabilize the areas not affected by pathogens.

2.Analysis of Ma Huang Fang from the Perspective of Wind-Cold

Mr. Zhao’s Ma Huang Fang is named similarly to the Ma Huang Tang from Shanghan Lun, differing by only one character. It consists of 9 herbs: Ma Huang (Ephedra), Xing Ren (Apricot Kernel), Gan Jiang Pi (Dried Ginger Peel), Zi Bei Fu Ping, Bai Xian Pi (White Fresh Skin), Chen Pi (Aged Tangerine Peel), Dan Pi, and Bai Jiang Can (White Silkworm), and Dan Shen (Salvia). This formula is primarily used for chronic urticaria or acute urticaria induced by cold-dampness in individuals with a constitution of blood deficiency.

“Cold invades internally, treated with sweet heat, assisted with bitter and pungent,” where pungent is used to disperse wind, sweet heat warms yang and disperses cold, and bitter is used to dry dampness.

Ma Huang Tang is the most representative formula for treating exogenous wind-cold with exterior excess, composed of Ma Huang, Gui Zhi (Cinnamon Twig), Xing Ren, and Zhi Gan Cao (Honey-Fried Licorice). In this formula, Ma Huang is bitter and pungent, warming and can induce sweating to release the exterior; Gui Zhi assists in enhancing the sweating effect; Xing Ren descends lung qi and disperses wind-cold; and Zhi Gan Cao harmonizes the other herbs and moderates their effects, preventing excessive sweating that could harm the righteous qi. Together, they form a pungent-warming and strong sweating formula.

However, Mr. Zhao’s Ma Huang Fang follows the principles of Ma Huang Tang but does not rigidly adhere to its ingredients. Chronic urticaria does not resolve with a single sweat as in acute cases, thus while it takes the principle of dispersing cold and inducing sweating from Ma Huang Tang, it adjusts the herbs to transform the strong sweating method into a gentle sweating method. With the assistance of Gui Zhi, the sweating power of Ma Huang is strong, but removing Gui Zhi from the formula shifts the focus to lung dispersal while sweating becomes secondary, resembling the San Ao Tang.

Mr. Zhao removed Gui Zhi from Ma Huang Tang to reduce its strong sweating power, and based on the characteristics of skin diseases, added Gan Jiang Pi, Zi Bei Fu Ping, Chen Pi, and Bai Xian Pi to assist Ma Huang in opening the pores, dispersing cold, and eliminating dampness; since chronic urticaria has a longer course, he included Bai Jiang Can, Dan Shen, and Dan Pi to disperse pathogens from the blood level, and both Dan Pi and Dan Shen are cold in nature, providing a counterbalancing effect, ensuring the formula has both cold and heat properties, thus avoiding exacerbation of skin symptoms due to excessive warmth and dryness.

3.Analysis of Quan Chong Fang from the Perspective of Damp-Heat

Mr. Zhao’s Quan Chong Fang consists of 9 herbs: Quan Chong (Scorpion), Zao Jiao Ci (Soapberry Thorn), Yuan Zhi (Pig Tooth Soapberry), Cang Zhu (Tribulus), Hua Jiao (Sophora Flower), Wei Ling Xian (Clematis), Ku Shen (Sophora Flavescens), Bai Xian Pi, and Huang Bai (Phellodendron). This formula is most suitable for treating “stubborn damp-heat accumulated deeply.” Quan Chong Fang is considered the most difficult formula to understand, as its name and composition do not easily connect with exogenous diseases. However, if we step outside the realm of herbs and focus on the core pathogenic mechanism it addresses, all doubts can be resolved.

Mr. Zhao stated regarding Quan Chong Fang: “If the spleen and stomach qi is stagnant, it leads to dampness; if dampness accumulates for a long time, it generates toxins; stubborn dampness and accumulated toxins affect the skin, causing unbearable itching.” This pathogenic mechanism is very similar to “damp-heat” in exogenous diseases. Wu Jutong discussed dampness in Wen Bing Tiao Bian: “Dampness is a yin pathogen, arising from the long summer, its onset is gradual, and its nature is humid and sticky, unlike cold pathogens that can be resolved with a single sweat or warm pathogens that can retreat with a single cool treatment, thus it is difficult to resolve quickly.”

Transitioning from “dampness” to “damp-heat” requires a prolonged disease course. In traditional medical cases, the term “damp-heat” is often used. Therefore, dampness in exogenous diseases can transform into damp-heat over time, and in skin diseases, it can accumulate into damp-toxins.

The challenge in treating damp-heat lies in transforming dampness, with basic principles being “wind overcomes dampness,” “bitter warms and dries dampness,” and “lightly draining dampness.” Through the flexible combination of these three types of herbs, the goal of treating dampness can be achieved. For the warm-heat pathogens generated by dampness, bitter-cold herbs can be used appropriately, but one must avoid using excessively cold herbs that could suppress and freeze the pathogens. In Quan Chong Fang, Wei Ling Xian and Cang Zhu are warming and dispersing dampness (Cang Zhu is classified as a wind-dispelling herb in Chinese Herbal Medicine, but it is widely used for damp-heat, being one of the most frequently used herbs in Wang Fengchun’s ten methods for treating dampness, and both herbs are used in significant quantities, up to one tael (30 grams). Although Quan Chong has a weak ability to disperse dampness, it belongs to the category of insect herbs, which excel at expelling stubborn wind-dampness from the meridians, making it most effective for chronic wind-damp diseases, thus it is the monarch herb of this formula; Zao Jiao Ci and Yuan Zhi are bitter-warming and drying dampness, with Yuan Zhi also having the effect of treating dampness obstructing bowel movements. In Wu Jutong’s formula for “damp-heat lingering, with the three burners diffused, spirit clouded, lower abdomen hard and full, and constipation,” Yuan Zhi is a core herb; Ku Shen, Bai Xian Pi, and Huang Bai are bitter-cold and drying dampness; Hua Jiao can also be used in large quantities, up to one tael (30 grams), as it has the dual effect of cooling blood and dispelling dampness, which is a characteristic of herbs used in skin diseases.

4.Conclusion and Outlook

Mr. Zhao Bingnan’s experience formulas are recorded in the book Clinical Experience Collection of Zhao Bingnan, which provides explanations of each formula from the perspective of dermatology. Although skin diseases have their specialized characteristics, the overarching treatment principles remain “drain if excess, tonify if deficiency.” From the perspective of TCM disease classification, diseases are primarily divided into exogenous and endogenous categories. Dermatological diseases can broadly be classified as exogenous diseases based on their etiology and pathogenic evolution. From a Western medical perspective, dermatological diseases are primarily infectious diseases and immune-related diseases; infectious diseases fall under the category of exogenous diseases, while immune-related diseases may also have some exogenous factors mixed in, similar to exogenous diseases arising on the basis of endogenous injuries. By integrating classical TCM theory on exogenous diseases to analyze Mr. Zhao’s “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment,” it is evident that his formulation approach is rooted in classical principles, categorizing dermatological diseases into those leaning towards wind-heat, wind-cold, and damp-toxins, respectively creating the Jing Fang, Ma Huang Fang, and Quan Chong Fang. However, Mr. Zhao’s prescriptions also transcend classical approaches; the specific herbs used in the “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment” closely align with the characteristics of dermatological diseases, incorporating specialized herbs for cooling blood and stopping itching. Therefore, Mr. Zhao’s formulation of the “Three Formulas for Wind Treatment” exemplifies the inheritance and promotion of TCM scholarship.

Currently, TCM faces challenges in inheritance, with a common phenomenon being the discussion of innovation and development without adequately inheriting the experiences of predecessors, leading to a facade of false prosperity in TCM scholarship. We must start with ourselves, earnestly learning and inheriting the rich experiences accumulated by Mr. Zhao in dermatology, and on that basis, develop and innovate in response to the changes in today’s disease spectrum. For example, the book Clinical Experience Collection of Zhao Bingnan contains many experiences for treating acute infectious diseases, including prescriptions, medical cases, and the preparation and usage methods of external ointments. These formulas treat many bacterial infections, successfully curing numerous infectious diseases before the widespread use of antibiotics. With the advent of antibiotics, infectious diseases have been well controlled, but immune-related dermatological diseases are on the rise, and clinical antibiotic resistance is becoming increasingly prominent. Whether we can draw from Mr. Zhao’s experiences to address today’s new problems is something we need to contemplate.

This article was published in the Beijing Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2019, Issue 8, with slight modifications.